Massive El Niño gains strength, likely to drench key California drought zone

Photographer Travis Geske, left, and California Highway Patrol Officer Edward Stewart rescue TV cameraman Monte Duarte, who was sinking in the mud during a mudslide caused by heavy rains on California 58 east of Tehachapi on Oct. 16.

- Share via

One of the most powerful El Niños on record continues gathering strength and is looking increasingly likely to bring heavy rains to key Northern California areas that provide water for the rest of the state, according to a new forecast.

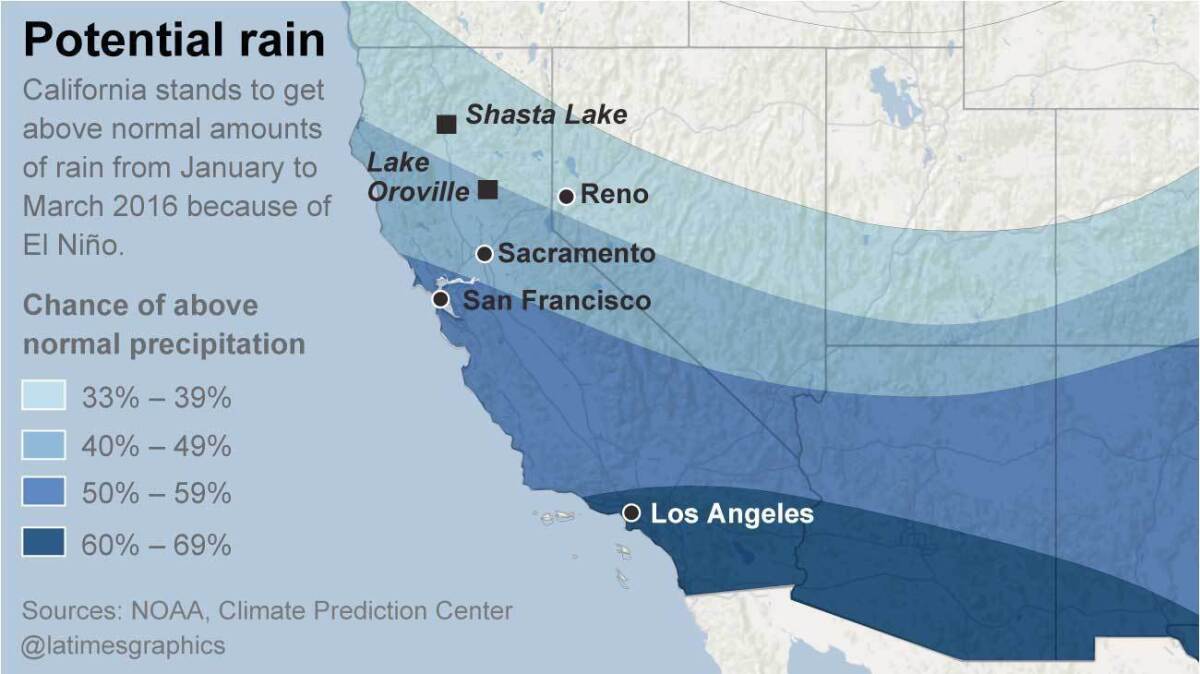

There are better odds that the area around Lake Oroville, California’s second-largest reservoir, will have above-normal precipitation -- now more than a 40% chance, up from a more than 33% chance in last month’s forecast. San Francisco now has more than a 50% shot of a wetter-than-average winter, up from a more than 40% probability.

Los Angeles continues to have more than a 60% probability of a wet winter during the months of January, February and March. Officials are scrambling to prepare, including clearing out basins and making sure roads are ready for all the rain.

Water and Power is The Times’ guide to the drought. Sign up to get the free newsletter >>

The chance of a wetter-than-average winter has increased in California, according to a new forecast by the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center released Thursday.

Here are some questions and answers about the coming winter.

Why is there more confidence that Northern California will have a wetter-than-normal winter?

Not only are we getting closer to winter, but El Niño is maintaining its strength and even getting stronger, said Matthew Rosencrans, head of operations for the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center.

“From the latest observation, it’s still on an upward trend,” he said, “not even topping out right now.”

Is there any chance El Niño will suddenly collapse?

Not really. There is a 95% chance that El Niño will persist through the spring, the Climate Prediction Center says.

El Niño is a warming of ocean waters west of Peru that can cause dramatic changes to the atmosphere, altering weather patterns worldwide. In the past, it has meant that the path of winter storms that normally keeps the jungles of southern Mexico and Central America wet moves north, over California.

That pattern has traditionally meant drought in Central America and southern Mexico, and a wet winter for northern Mexico and the southern United States. (It has also meant the best surfing season in a generation, from the coast of British Columbia to Costa Rica.)

Why are scientists so confident that El Niño won’t suddenly disappear earlier than expected?

The pool of warm water in the Pacific Ocean west of Peru is huge and very deep. “There’s been a tremendous distribution of heat, and that is definitely not going away” any time soon, said Bill Patzert, climatologist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge. “I’m quite optimistic that the entire state is going to get hosed.

“This El Niño is so dramatically large. It’s so intense. It’s hard to imagine that it won’t deliver,” Patzert said.

How big is this warm water in the Pacific Ocean west of Peru?

“It’s about 8 million square miles of overheated ocean,” Patzert said. “The United States is only 3 million square miles. So this is about two and a half times the size of the continental United States.

“This thing is pumping moisture out of the overheated ocean into the atmosphere above, which of course means it’s having a huge impact and rearranging all the pieces on the weather board across the planet.”

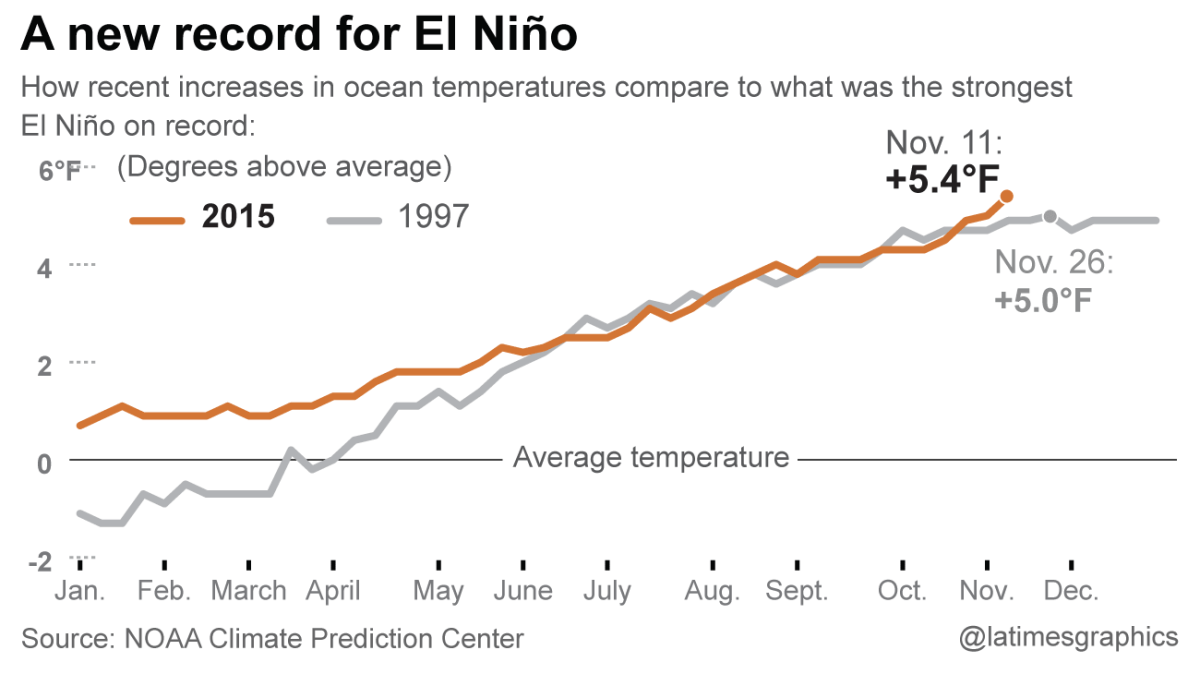

This El Niño is rivaling the two most powerful El Niños on record, which occurred in 1982-83 and 1997-98.

When are the El Niño rains expected to come?

In 1983, El Niño rains came in earnest in January, Patzert said. In 1998, the biggest storms statewide didn’t kick in until February, he said.

Daniel Swain, climate scientist for Stanford University, said he suspects that at some point during December, the weather pattern will change, “and certainly by January, February and March we’ll see above-average precipitation -- potentially well above-average.”

By then, Patzert said, Californians should expect “mudslides, heavy rainfall, one storm after another like a conveyor belt.”

What does a month of El Niño storms look like?

“A whole convoy of storms coming out of the west,” Patzert said. In February 1998, Los Angeles saw 14 days of storms and 14 days of dry weather, Patzert said, from four big storms and two small ones.

That’s a lot for Los Angeles. A good winter for Los Angeles is half a dozen big storms. An El Niño winter can bring 12 to 15 storms, Patzert said.

The mountains of far Northern California can get a lot more rain in a big El Niño. That’s why our state’s largest reservoirs were built up there, and officials built one of the most extensive aqueduct systems in the world to ferry that water down to the rest of the state, including Los Angeles.

“What we want to see is that aqueduct flowing,” Patzert said. “I want to see that water rush down the California Aqueduct toward Lake Castaic.”

Were the recent snowstorms that allowed ski resorts to open so early this year due to El Niño?

Actually, no, Patzert says. El Niño storms come straight from the west from an area of the Pacific Ocean north of Hawaii; November’s snowstorms originated from the Gulf of Alaska.

That’s what brought very chilly weather and lots of snow to the resorts at Lake Tahoe. One single storm brought 20 inches of powder to Mammoth Mountain, cheering skiers and snowboarders.

Is that a sign that the persistent weather pattern that plunged us into a deep, devastating drought is weakening?

Yes, Patzert said. The drought in recent years has been worsened by a mass of high pressure deflecting typical winter storms that swoop into California from the Gulf of Alaska.

That mass of high pressure generated warmer-than-normal ocean water in the northern Pacific, which became dubbed “the blob.”

November’s snowstorms suggested that the drought-causing mass of high pressure “doesn’t seem to be playing the role it has been in the last few years,” Patzert said.

“This is the earliest the ski resorts have been opened in many years. ... They rarely open before Thanksgiving.”

Especially important is that it has been cold.

“For California ski resorts, snow is good but what really counts is temperature. So the key for Big Bear and Mammoth is that the temperatures are cold enough to make snow. And it has been cold,” Patzert said.

Whether the cold snap lasts through spring is an open question. The Climate Prediction Center has forecast above-normal temperatures this winter for California.

Overall, what’s the outlook for the ski season?

It will probably remain the best ski season in years, because ski resorts are so high in elevation. “The really high elevations in the Sierra Nevada will do well,” Stanford’s Swain said.

But what about the mountains that are important to the state’s water supply?

No one has a good answer for this. The mid-elevation mountains of Northern California are very important to the state’s water supply, and it’s important that precipitation comes as snow, not rain.

Too much rain all at once will force excess water to be flushed out to sea to prevent dams from being overwhelmed. But if snow falls, it can melt slowly in the spring and summer, gently replenishing reservoirs.

Scientists generally agree that more precipitation is likely in these mid-elevation mountains. But whether it’ll fall as snow or rain isn’t known.

What have the strongest El Niño winters brought to California in the past?

A lot of rain, snow and devastation.

After the El Niño that developed in 1997 became the most powerful on record, the following winter gave Los Angeles double its annual snowfall and dumped double the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada, Patzert said.

The 1982-83 El Niño was the second most powerful El Niño on record; the soaking that shocked California in the early months of 1983 brought the mountains of Northern California the wettest year on record, giving the area 1.9 times the average annual precipitation, according to Kevin Werner, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s expert on climate in the western United States.

Generally, El Niño storms themselves are not particularly intense. The problem is that there are so many storms that come one after another.

For instance, downtown Los Angeles in February 1998 saw six storms. That is a lot for Los Angeles -- a good year for L.A. is six big storms; that many weather systems in a single month was overwhelming.

That winter, 17 people died in California, and more than half a billion dollars’ worth of damage occurred. Flood-control channels overflowed, mudslides destroyed hillside homes and roads, and railroad tracks were washed away.

What isn’t expected in an El Niño?

Patzert says Pineapple Express storms -- the kind that come from south of Hawaii and bring excessive rain in a short amount of time -- aren’t typically seen during an El Niño.

“They’re the storms where you get 10 inches in 24 hours. The El Niño storms aren’t like that,” he said.

An example of a Pineapple Express storm was the storm in 2010 that dumped rain at an alarming rate over the mountains that burned in the massive Station fire, unleashing a torrent of mud that inundated more than 40 houses in La Cañada Flintridge, Patzert said.

How hot is this El Niño?

Ocean waters west of Peru are now hotter than recorded in at least 25 years, surpassing the temperatures during the record 1997 El Niño. It is the highest such weekly temperature recorded in 25 years of modern record-keeping in this key region of the Pacific Ocean west of Peru.

Temperatures in this key area of the Pacific Ocean rose to 5.4 degrees above average for the week of Nov. 11. That exceeds the highest comparable reading for the most powerful El Niño on record, when temperatures rose 5 degrees above the average the week of Thanksgiving in 1997.

In fact, last week was the hottest this area of the Pacific Ocean has been since 1990, when records began being kept meticulously. It was 85.46 degrees as of Nov. 11, surpassing the 85.1-degree record hit a week before. Prior to that, the record high was 84.92 degrees set the week of Thanksgiving in 1997.

Will this El Niño end the drought?

That’s virtually an impossibility. By one calculation, California’s mountainous north would need 2.5 times to three times its average precipitation to end this drought, and the record is just nearly double the average annual rain and snowfall.

A big question is also what comes after this El Niño ends -- and it could be renewed drought.

“My scenario is that the El Niño delivers as expected, and then El Niño switches to a La Niña, which is what happened in 1998,” Patzert said, which brings drought. “It went into two years of below-normal snowpack and rainfall,” and the start of a dry spell.

El Niño historically can’t be counted on to keep California wet. The last big El Niño came 17 years ago, and they come too infrequently for California to rely on. California gets more of its water over a 25-year period from storms from the Gulf of Alaska and Pineapple Expresses instead.

“Over a 25-year period, over the long term, El Niño provides only 7% of our water. So as much as we’re hyping it, it’s not a big player,” Patzert said. “It’s fast and furious, but it’s too irregular – the gap between El Niños is too long to build any statues to El Niño to be a drought-buster. If we were going to build a drought-buster statue downtown, it would be North Pacific storms or Pineapple Expresses.”

Can you explain more about how the Climate Prediction Center estimates the chance of precipitation this winter?

These calculations start off with the idea that there is a 33% chance of above-average precipitation, a 33% chance of average precipitation, and a 33% chance of below-average precipitation.

So here’s a more detailed way to read the first map in this blog post:

Los Angeles has a more than 60% chance of a wetter-than-average winter, a 33% chance for an average-precipitation winter and a less than 7% chance of a drier-than-normal winter.

San Francisco has a more than a 50% chance of a wetter-than-average winter, a 33% chance for an average-precipitation winter and a less than 17% chance of a drier-than-normal winter.

For Sacramento and Lake Oroville, there’s more than a 40% chance of a wetter-than-average winter, a 33% chance for an average-precipitation winter and a less than 27% chance of a drier-than-normal winter.

Shasta Lake has a more than 33% chance of a wetter-than-average winter, a 33% chance for an average-precipitation winter and less than a 33% chance of a drier-than-normal winter.

Staff writers Lorena Iñiguez Elebee and Raoul Rañoa contributed to this report.

Follow us for the latest news in earthquake safety, El Nino, and the drought: @ronlin and @RosannaXia

ALSO

L.A.’s chronic homelessness population is largest in the nation

Quake retrofit grants expanding to more California single-family homes

Airport commission approves a private LAX lounge for the rich and famous