What happened to Cudahy when a 29-year-old took over as mayor

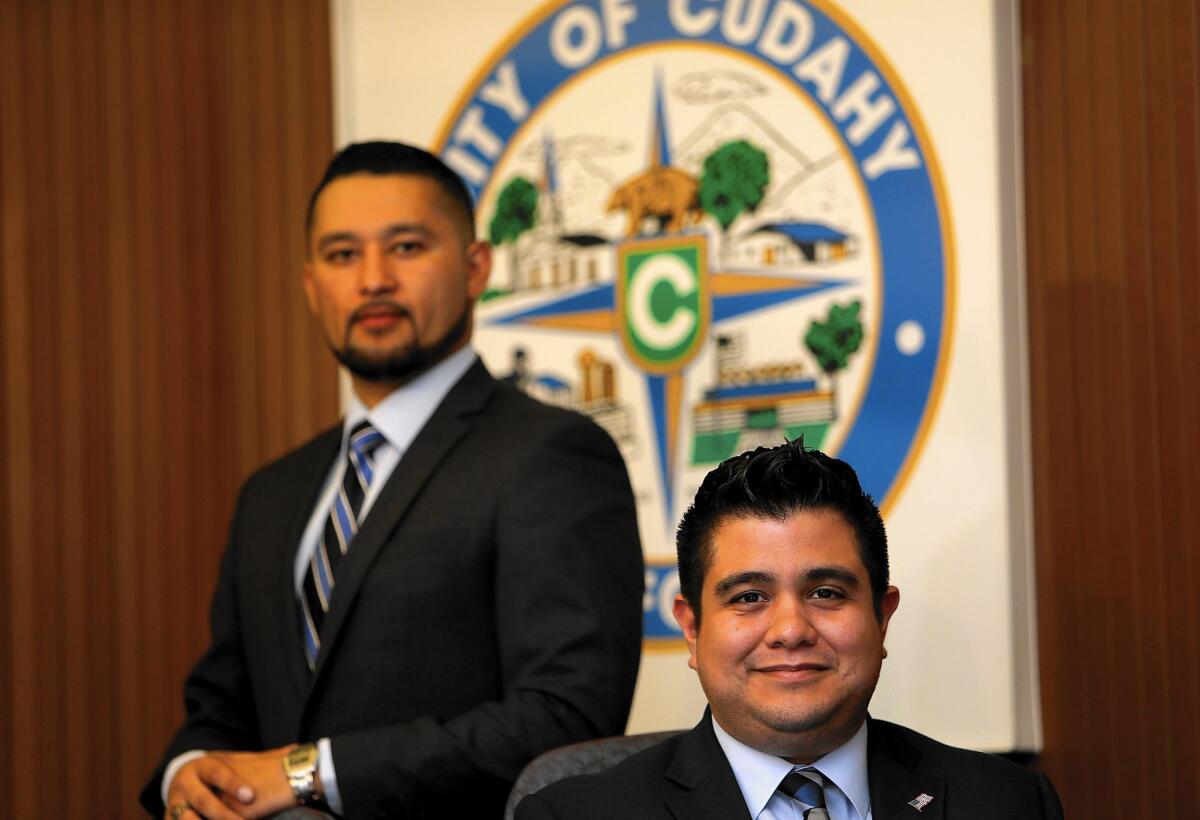

“Technology is playing a critical role not just for us millennials but Latinos in general,” said Cudahy Vice Mayor Christian Hernandez, 26, left. With him is Mayor Cristian Markovich, 29.

- Share via

After the dust settled and the FBI had scoured through town on the hunt for crooked politicians, the voters of the city of Cudahy cleaned house.

But they didn’t just elect new politicians. They elected younger ones, with college degrees — millennials with the know-how to use Twitter, Facebook and other social media to deliver their messages to residents.

Gone were skeletal city websites that almost seemed designed to share no meaningful information, replaced with more in-depth sites.

Just below the framed photos of the five Cudahy council members at City Hall is a sign with a bar code that people can use to download the agenda on their smartphones. Most of the residents on a recent night walked past the sign and went straight to physical copies sitting on a glass counter. But the bar code underscored the direction Cudahy officials want to go in a predominantly Latino city of 24,000 where the average person is only 22 years old.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

“We need to embrace the fact that technology is playing a critical role not just for us millennials but Latinos in general,” said Cudahy Vice Mayor Christian Hernandez, 26, who has a degree in political science from UCLA. “We’re a poor region but everyone owns a smartphone.”

The heavily immigrant, working-class towns along the 710 Freeway have long struggled with municipal corruption, in part because there was little public scrutiny of City Hall. A new generation of younger leaders now believes technology can lead to more transparency, and participation.

In Maywood, high school students in September used Facebook to reach out to Maywood Mayor Eduardo De La Riva about creating a 5K run. They presented a map of the course to the council last month.

Diana Gastelum, 17, a Bell High School student, said social media make politicians accessible and “you feel less nervous about it.”

“The way technology is going, there are so many different ways to reach out to people but I mostly use Facebook,” she said. “I had him as a Facebook friend and it was easier to contact him.”

Whether this new push will be a long-term game changer in a region of Los Angeles County with historically low voter turnout and a reputation for political corruption remains to be seen.

But Cudahy Mayor Cristian Markovich, 29, said it would be hard to argue that serious change hasn’t taken place.

“We have a city hall that is running 24 hours, seven days a week,” Markovich said. “Residents can reach us by email, social media, phone or they can do it the old-fashioned way — by making an appointment.”

The mayor added: “Sometimes we joke the scandal was the best thing for the city.”

Secrecy used to be at the center of how several city halls in southeast L.A. County operated.

Politicians with questionable intent had a built-in advantage: A large percentage of the population in towns such as Cudahy, Bell, Maywood, Huntington Park and South Gate was made up of immigrants without legal status who could not cast votes. Fearful of drawing attention to themselves, they were also less likely to complain to authorities if they suspected something was wrong in city hall.

Those residents who did come forward, demanding information, were sometimes lied to. That happened in Bell, to one man who suspected then-City Manager Robert Rizzo was being paid a troublingly high salary. Bell provided him with forged records that understated his compensation. When the Los Angeles Times eventually revealed that Rizzo made at least $800,000 a year, a scandal that drew national attention broke out. (Rizzo’s total yearly compensation turned out to be about $1.5 million.)

In Cudahy, people running against council incumbents were targets of smear campaigns. In at least one case, a candidate had a Molotov cocktail flung at his house. An FBI affidavit described a bribe given in a shoe box at a Denny’s; it described rigged elections and drugs being used at city hall as well as city workers being used as armed bodyguards for the small town politicians.

Then-Cudahy Mayor David Silva, Councilman Osvaldo Conde and city employee Angel Perales were arrested and convicted of accepting $17,000 in bribes in exchange for allowing a marijuana dispensary store to open in their city.

After the revelations and scandals, Cudahy voters elected council members who were younger; today four of the city’s five elected politicians are in their late 20s. And all five of the council members graduated from Cal State Long Beach, UCLA or Stanford.

In neighboring Huntington Park, the council members are even younger, with four of the five in their 20s. Young and college-educated council members were also elected in Bell and Maywood.

“What you’re seeing is those of us who were raised here went off to college, we went out to establish our careers and have come back to reclaim our cities,” said De La Riva, 38.

Nina Eliasoph, professor of sociology at USC, said what is happening in the southeast is the swapping of a system that became corrosive and stopped working for another one.

“The old one was based on local friendships and ties,” she said. “The new one promises to be more open and accessible to everyone.”

But she said the emerging political way of doing things depends on how much residents actually participate and keep tabs on their city halls.

Early this year, when trash began piling up in Huntington Park because of a new trash hauling contract, Mayor Karina Macias, 28, took to Facebook to keep track of residents’ complaints.

The new council in Huntington Park brought back city commissions and created a new one, the Youth Commission, to receive feedback from younger residents. Eager to participate, two immigrants living in the U.S. illegally but with college degrees sought to volunteer in August.

As the council considered the appointments, residents who opposed the idea took to social media to raise awareness and opposition. Others did the same to support the appointments, which ended up being made.

“Millennials are more open to gay marriage and immigration,” Macias said. “Most of the people who came to the podium that night were young people who were open to the idea of having undocumented commissioners.”

Macias, who voted in favor of the move, said that one challenge presented by the emergence of social media in cities that once seemed to shun transparency is the near-constant — and more digitally immediate — questioning of elected officials’ ethics.

“I think public trust is always going to be a constant challenge for any public official,” she said. “But it becomes more of a challenge with social media — to see what they’re saying about you in tweets, blogs or Facebook.”

She said responding to accusations online also has it limits.

“At the end of the day, nothing beats door to door,” Macias said.

In Cudahy, the city is in the midst of changing its motto from “Serving the People” to “The Future Starts Here.” Officials say they want to create jobs by tapping into the booming tech industry. But to do that there has to be a cultural shift where “we have to incorporate technology in our everyday talk.”

“It’s kind of like what former Apple CEO John Sculley did: You just point the ship forward and fix the leak,” Markovich, the Cudahy mayor, said. “We’re now just starting to build things.”

Twitter: @latvives

ALSO

California tax board mishandled money, state controller’s audit finds

Heartbroken man spends more than $700,000 on psychics, chasing after lover

Taxpayers will pay billions more as CalPERS lowers estimate of investment returns

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.