Orange County teacher is on a mission to preserve Telugu, a language that’s endangered in U.S.

Vidya Tandanki hosts the Telugu Thota school in her Irvine home to teach children the ancient language.

- Share via

Three nights a week, Vidya Tandanki works at trying to save an ancient language perceived as threatened in some parts of the globe.

She hosts children in her Irvine home, where she has converted her garage into a classroom. It is painted bright turquoise with colorful posters and paintings hanging on the walls and also has a computer station, white boards, supply cabinets and rugs covering the floors.

There she teaches them Telugu, the children’s mother tongue, which is mainly spoken in India. On a recent Friday night, Tadanki, speaking English, asked her advanced students what they did over the holidays, and they responded easily in Telugu. After some translation exercises, the children, ages 9 to 14, sang songs and recited poetry.

Telugu is spoken by 75 million people worldwide, but it has become increasingly rare among second- and third-generation Indian Americans.

“For them, it’s a foreign language even though it’s their mother tongue,” the teacher said.

So for the last 13 years, Tadanki has been running the popular language school Telugu Thota, serving hundreds of children.

“Our language is vulnerable; it’s definitely endangered,” she said. “Children no longer learn the language in the home. So after 40 or 50 years, what will happen?”

Vidya Tandanki works with students at her home-based Telugu Thota school in Irvine.

Tadanki started Telugu Thota — which means Telugu Garden — in 2003, a year after she and her family moved to Irvine.

She had been teaching the language to her own children for years, when they lived in New Jersey and San Jose. Not only was it a way for them to learn about their heritage, but it was also practical, because the family continued to visit India regularly.

“When my kids go back to Andhra Pradesh,” she said of the southeastern state where she grew up, “they shouldn’t feel like a fish out of water.”

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

It was only after Tadanki moved to Irvine that someone suggested she formalize and expand her lessons to include other children in the community.

According to Bayapa Dadem, president of the Telugu Assn. of Southern California, about 5,000 Telugu families live between Los Angeles and San Diego, with Orange County being the biggest hub in the region. Orange County’s Telugu population is the fourth- or fifth-largest in the country, he said, and it has been growing for the last decade.

Tadanki’s first public class had seven students — her son and some of his friends — and was held in an extra room in the family house.

“Within five minutes of that class starting, the kids were giggling, laughing, pretending to be an elephant,” said Sravani Jandhyala, an Irvine resident whose children, then 4 and 6, were students in Tadanki’s first class. “She was not communicating to them in English at all, yet they were completely engaged and no one asked when the class would end, even though it went well above an hour.”

Although Tadanki had never taught Telugu before, she had experience with language instruction. Before moving to Irvine, Tadanki, who studied English literature in college, taught English to non-native speakers at a San Jose school.

“Teaching English to Spanish-speaking kids is the equivalent to teaching Telugu to American Indian kids who think, talk, read, write — everything — in English,” she said.

“The first thing the parents say are, ‘My kids are talking to their grandparents,’” Tadanki said. “Most of the grandparents can’t speak English, so the parents are saying, ‘Thanks to this, they’re having phone calls with them and conversations on WhatsApp,’” a cross-platform mobile messaging app.

Although other Telugu language classes exist in Orange County — mostly run out of Hindu temples or organizations such as the Telugu association — Tadanki’s has gained credit for her creative approach to teaching.

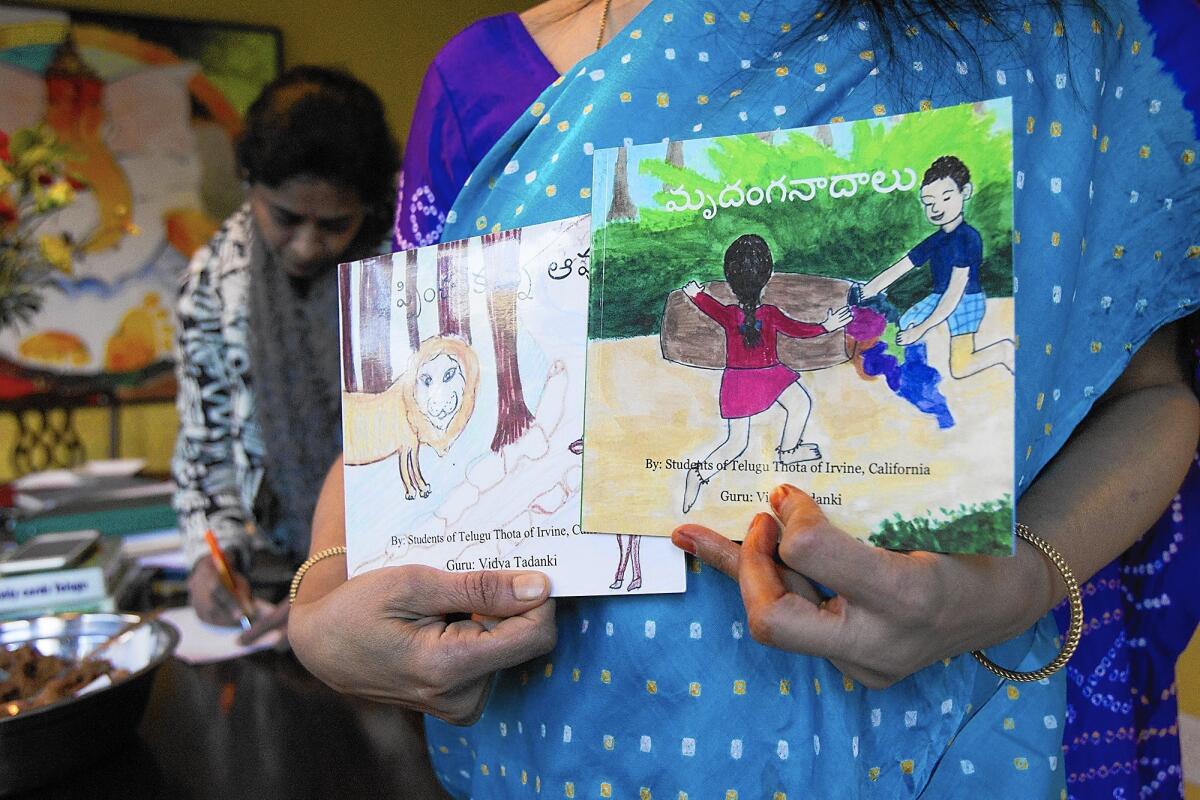

Because Telugu textbooks are rare, if not nonexistent, in the United States, Tadanki developed her own based on the materials she used from teaching in San Jose. Her students also wrote and illustrated several beginner-level storybooks, which Tadanki had published.

Vidya Tandanki displays books created by students at her in-home Telugu Thota school in Irvine.

Parakash Kasturi, an Irvine resident whose two sons are enrolled in Telugu Thota, said that part of his motivation for moving to Irvine from Rancho Santa Margarita was to be near Tadanki’s classes and the community that had formed around her.

“One of my family friends told me, ‘There’s Telugu Thota here, Vidaya’s here, the community is around Irvine,’” he said. “So my wife and I said, ‘OK, we have to pick a house that’s close by.’”

Caitlin Yoshiko Kandil writes for Times Community News.

ALSO

O.C. Sheriff’s Department examines what went wrong as fugitives return to jail

Obama invites L.A. teen with perfect AP Calculus exam score to White House Science Fair

Winds topping 115 mph hit Southern California; 1 killed when tree falls on car

More to Read

Get the Latinx Files newsletter

Stories that capture the multitudes within the American Latinx community.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.