Disneyland, holiday travel a perfect mix for measles’ spread

- Share via

The measles outbreak happened at a vulnerable place and at a bad moment.

Disneyland was filled with holiday tourists from around the world the week before Christmas when someone with measles spread the disease. With its packed walkways, long lines and enclosed spaces, the theme park offered prime conditions for measles to spread and travel as visitors returned home.

Since then, at least 26 patients have been identified in California, Utah, Colorado and Washington state, and there are probably more out there.

Health officials said the outbreak was the worst in California in 15 years, in part because it occurred not in a small, insular community but at a crossroads of the world.

“Disneyland — this is the ideal scenario. This is sort of the perfect storm,” said Dr. James Cherry, a UCLA expert on pediatric infectious diseases. “People go to Disneyland, and they went from all different counties and all different states.”

Quelling the outbreak has taken on special urgency as measles cases have increased dramatically in the last year and as child immunizations have dropped. This decline has come amid fears of some parents that the vaccines can cause autism, a theory that has been discredited by numerous scientific reports.

A “significant number” of the Disneyland patients involved people who were not immunized, said Dr. James Watt, who heads the California Department of Public Health’s division of communicable disease control.

The Disneyland cases come months after another measles outbreak involving travelers returning from the Philippines. Dr. Gil Chavez, the state’s epidemiologist, said in that case, many of the patients “had not been immunized, either because their parents had declined childhood immunization for them or because they were too young.”

The problem is now spreading as those who visited Disneyland between Dec. 17 and 20 have gotten on planes and returned home to far-flung places. In Grays Harbor County, southwest of Seattle, an unvaccinated young woman was diagnosed with measles. Seattle-Tacoma International Airport and nearby Snohomish County are also on alert after an unvaccinated California woman in her 20s flew to see family while contagious.

Utah officials have tracked down more than 380 people who could have come in contact with two vacationers who got the measles and asked many of them to quarantine themselves at home for 21 days. In Colorado, one older adult became infectious after returning to the Colorado Springs area; it was the first case in the state’s El Paso County since 1992.

Officials in California and the nation are scrambling to get ahead of the outbreak, mapping out scenarios and identifying public locations where contagious people have been. Those places include a Ralphs grocery store in San Clemente, a Starbucks in Laguna Beach and the Morongo Casino Resort & Spa in Cabazon.

Long Beach investigators interviewed the city’s lone measles patient and put out a public alert for unvaccinated people who went to Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Stater Bros. or Total Wellness Club on East Spring Street in the late morning of Jan. 3.

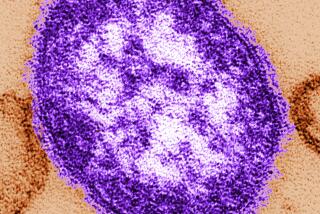

Controlling measles is difficult, because the patient is infectious as soon as coughing and sneezing begins but before the telltale rash appears — first on the head, then spreading to the rest of the body. Patients can be contagious four days before the rash appears and four days after, said John Holguin, epidemiology program supervisor for Long Beach.

Other symptoms include fever, redness of eyes and runny nose. Those affected in the Disneyland outbreak range in age from 7 months to 57 years.

It has been the worst year for measles, both nationwide and in California, since domestic transmission of measles was eliminated in 2000. There were at least 644 cases of measles nationally in 2014, up from 189 in 2013. In California, there were 70 cases last year, up from 18 the previous year.

Since 2000, U.S. cases of measles have arrived from travelers from other parts of the world where measles is a problem, such as Europe and Southeast Asia. Eventually the disease transmission is snuffed out by vaccinated people.

But experts warn that declining vaccination rates are starting to pose a big risk. For many years until 2006, about 95% of California’s kindergartners were fully vaccinated for measles. That number has dropped to 92.6% — low enough to be dangerous. California kindergartners are required to get vaccines but can get a medical or “personal belief” exemption.

Those who support parental choice for vaccination said the latest incidents have not swayed them.

“I don’t think we should have a black-and-white approach and just say it’s the fault of the unvaccinated people,” said Barbara Loe Fisher, president of the National Vaccine Information Center. “You have the right to be fully informed about the benefits and risk of a medical intervention and [to] be able to make a voluntary choice without being harassed, coerced or punished for the choice you make.”

Health experts said choosing not to vaccinate puts children at grave risk of severe illness and death.

“You have a disease that can certainly cause hospitalization and death, and people play a very dangerous game when they choose not to vaccinate their children,” said Dr. Paul Offit, an infectious diseases expert at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases known and can be especially severe in babies, toddlers and adults. For every 1,000 children who get the measles, one or two will die from it, and one will get brain swelling so severe it can lead to convulsions and leave the child deaf or mentally retarded, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

Offit recalled the 1988-91 national measles epidemic. In California, there were about 75 deaths, most involving babies and children under the age of 5. Philadelphia saw nine children die in February 1991 in an outbreak centered on churches whose members didn’t vaccinate their children.

In Ohio last March, an unvaccinated Amish humanitarian aid worker came back from the Philippines with the measles, causing an outbreak that infected more than 380 people. The disease was stopped only by a robust campaign by health officials to administer 12,000 vaccination doses in the predominantly Amish community.

That was the largest outbreak of measles in the U.S. in the last 15 years, said CDC measles expert Paul Gastanaduy.

“It’s tricky with measles. You have to get ahead of the outbreak,” he said. “The way to stop it is to try to anticipate as much as possible who’s going to be susceptible and vaccinate them as quickly as possible.”

But the challenge with the Disneyland outbreak, he said, was the sheer number of people who visited from so many different places. “It becomes a distinct outbreak from a single community,” he said. “How big and severe it will be, it’s hard to say.”

In addition to the three other states, there are now 22 measles cases in California related to the Disneyland outbreak, in the counties of Alameda (3), Los Angeles (3), Orange (9), Riverside (2), San Bernardino (2), San Diego (2) and Ventura (1). At least six people have been hospitalized.

Disneyland said it is fully cooperating with health authorities.

“We are working with the health department to provide any information and assistance we can,” Dr. Pam Hymel, chief medical officer of Walt Disney Parks and Resorts, said in a statement.

More to Read

Get the Latinx Files newsletter

Stories that capture the multitudes within the American Latinx community.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.