George Deukmejian dead at 89, public safety and law-and-order dominated two-term governor’s agenda

- Share via

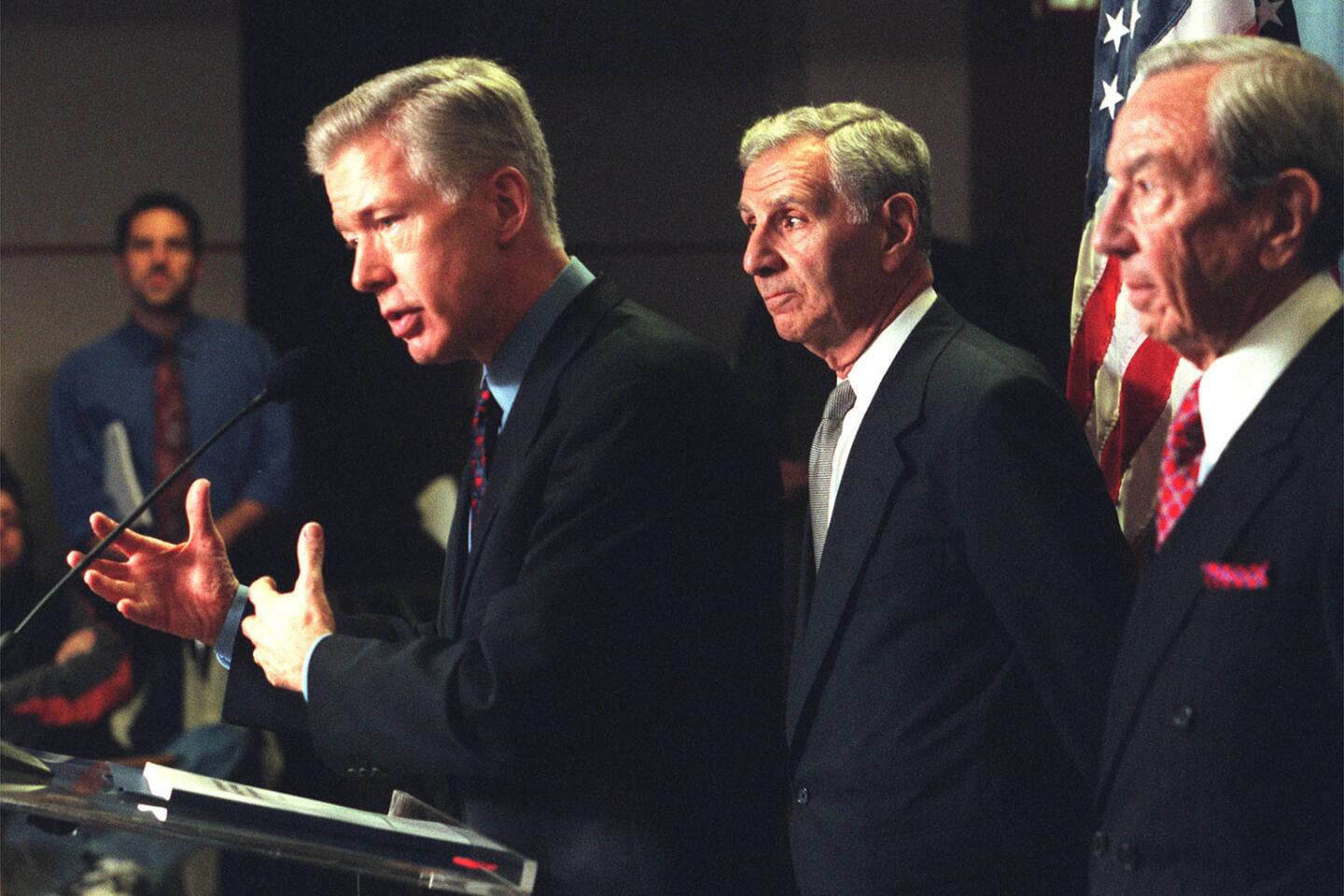

George Deukmejian, a perennially popular two-term Republican governor of California who built his career on fighting crime, hardening the state’s criminal-justice stance and shoring up its leaky finances, died Tuesday. He was 89.

Deukmejian, who was elected governor in 1982 and 1986, died at his home in Long Beach, according to a statement from his family.

During his many years of public service, including 16 years as a state legislator and four as state attorney general, Deukmejian sponsored the successful “use a gun, go to prison” bill, oversaw development of a workfare program for welfare recipients and negotiated with the Democratic-controlled Legislature to create an $18.5-billion, 10-year transportation plan.

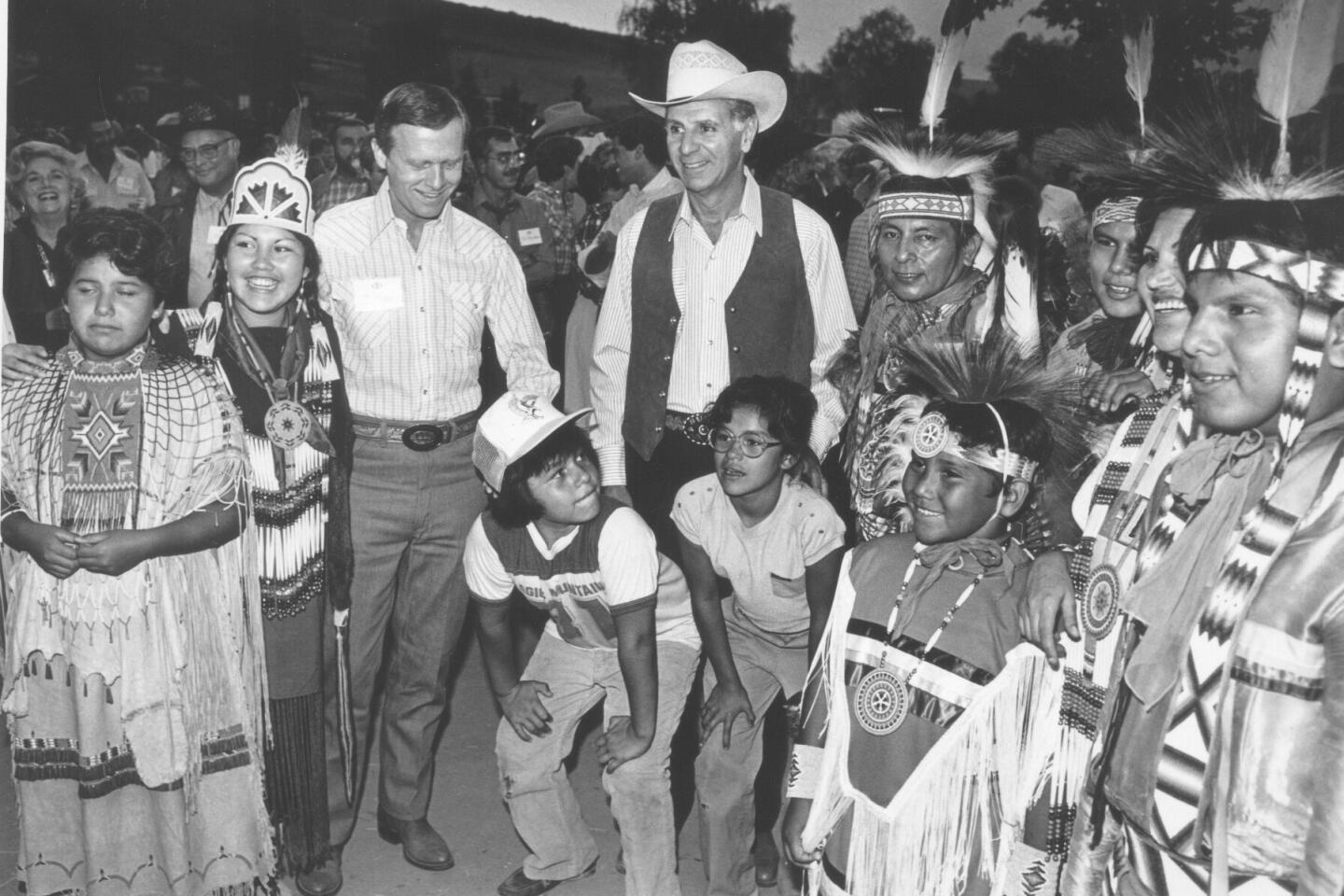

The son of Armenian immigrants, Deukmejian had years of public office on his resumé before winning election as governor and emerging as the most prominent Armenian American politician in the United States.

His identification with Armenians, who were victims of genocide during the early 20th century at the hands of the Ottoman Turks, would infuse his life with a determination to ensure the rule of law.

News of Deukmejian’s death brought praise from all corners of the state’s political community. The California Republican Party called him “one of the great governors of the last century,” and Gov. Jerry Brown noted that he had “friends across the political aisle.”

“Gov. Deukmejian’s humility and passion for doing what was best for California is a model for all who seek public service,” said Allan Zaremberg, president of the California Chamber of Commerce and Deukmejian’s former legislative affairs secretary.

Never, during a career that spanned three decades, did he waver from his law-and-order crusade or his passion for public safety.

Steven Merksamer, Deukmejian’s onetime chief of staff and longtime advisor, said that one way to understand his former boss was to realize that, for him, public safety — whether it be crime control or retrofitting bridges for earthquake protection — was part and parcel of a basic philosophy.

Coverage of California politics »

“The paramount reason he ran for governor in the first place was his commitment to public safety,” Merksamer said in 1989. “It has been the hallmark of his whole life — much more so than taxes or other issues. It’s something he has told me he was brought up with.”

After serving as California’s attorney general, he rode the crime issue into the governor’s office in 1982 and, during the eight years he governed the state, guided the criminal-justice system toward tougher sentencing. He also oversaw the expenditure of $3.3 billion to build eight new penitentiaries. The number of felons in prison tripled to nearly 97,000 during his tenure.

He also moved vigorously to put judges on the bench who took a hard line on crime.

Deukmejian had watched as his predecessor, Brown, appointed liberals to the court, including making the controversial Rose Bird the chief justice of the state Supreme Court.

When it was his turn, Deukmejian backed an initiative campaign — which voters overwhelmingly approved — to oust Bird and two other high-court justices, Cruz Reynoso and Joseph Grodin. As a result, Deukmejian was able to almost completely remake the court, appointing five of the court’s seven justices.

“The governor wanted justice to be sure as well as just, and to be perceived as such by Californians,” said Douglas W. Kmiec, who was constitutional legal counsel in the Reagan and the George H.W. Bush presidencies. “Deukmejian’s judges tended to be law-and-order judges. They knew the law well, and they did not look to make new law from the bench.”

Besides remaking the state Supreme Court, Deukmejian appointed a raft of conservatives, including many prosecutors, to the state’s lower courts. His appointments reached 1,000 by the time he left office in 1991.

In all, Deukmejian spent almost 28 years in Sacramento, enjoying a reputation as someone of unquestioned integrity but whose manner was so severe that he earned the nickname “Iron Duke.”

Deukmejian said he was not trying to be difficult but merely trying to “stick by my position and stick by my principles.”

Sign up for the Essential Politics newsletter »

Charles E. Young, who was chancellor of UCLA when Deukmejian was elected governor, said that he had wondered at first if he would be able to work well with Deukmejian. But Young came to view Deukmejian as one of the great modern-era governors of California.

“I believe he never took a position that he didn’t believe sincerely, and if he believed sincerely in it, it didn’t make any difference what anybody else thought,” Young told The Times.

Deukmejian was popular with voters who were anxious about crime. Unlike others before and after him, however, he did not try to ride his popularity to the White House, though he once conceded that, had he been asked to be George H.W. Bush’s running mate in 1988 instead of Dan Quayle, “I might have agreed to it.”

Although he played a part in California politics after he left office, attending Republican events and supporting various GOP candidates, he maintained a largely private profile. In 1991, he joined the Los Angeles office of the Sidley & Austin law firm, retiring 10 years later.

Deukmejian liked not having to run the state after he left office.

“You get up every morning and you don’t have to worry about 30 million people, deal with 120 legislators, deal with the press,” Deukmejian told The Times’ George Skelton in 1992. “It took me about five minutes to adjust to a private, normal life without all those concerns and headaches.”

Courken George Deukmejian Jr. was born June 6, 1928, in Menands, N.Y., a small village set among the rolling hills and aging brick factories along the Hudson River near Albany, the state capital.

At home, Deukmejian’s parents spoke Armenian, Turkish and English but taught George and his sister, Anna, only English. This experience left him with the belief that any child could learn another language and cemented his lifelong opposition to mandatory bilingual education classes in public schools.

The Deukmejian home was in the center of town next door to the police station and volunteer fire department.

“When I started to go to kindergarten, they would drive me in the [motorcycle] sidecar,” he once told the San Francisco Chronicle.

But it was something much more profound than these boyhood memories — the Armenian genocide in the early 20th century — that was the source of his passion for public order and motivated him to seek a political career.

Both Deukmejian and his wife, Gloria, also an Armenian American, had been raised on stories about the genocide. Deukmejian’s aunt was killed by Ottoman Turks, and his parents fled to America to escape persecution. During his entire political career, Deukmejian attempted to get official recognition for the genocide.

Deukmejian’s Armenian loyalties also led to one of the more surprising moves he made as governor: the 1986 decision to use his considerable influence to urge the University of California Board of Regents to immediately divest UC’s vast teacher and employee retirement funds from firms that did business in South Africa, which was then ruled by a white-minority government that imposed apartheid rule against the majority blacks.

As a staunch conservative, Deukmejian had previously vetoed a similar proposal by the Legislature to divest.

But about a year after his veto, South Africa was hunting down and jailing anti-apartheid activists, which troubled Deukmejian so deeply that he convinced two of his own appointees on the board of regents and the board’s Democratic appointees to support divestiture.

Deukmejian was raised in what a longtime friend described as “a typical Old World household” where politeness, family honor and hard work were the order of the day. He always stood up when his mother came into the room. Young Deukmejian was a choirboy and an acolyte. During his high school years, he wrapped meat at a butcher shop and made coat hangers. One summer, he picked crops at a nearby farm.

Deukmejian earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Siena College in Loudonville, N.Y. He dabbled during that time in politics, volunteering for the 1948 presidential campaign of New York Gov. Thomas Dewey.

“I was always interested in current events,” he said in a 2013 television interview.

In 1952, Deukmejian graduated with a law degree from St. John’s University School of Law in Brooklyn. Upon Upon Deukmejian’s graduation from law school, his student deferment expired and he was drafted into the Army, destined for a two-year infantry stint in Europe. But he convinced the brass to assign him to the Army Judge Advocate Corps in Paris.

In 1955, his military duty over, Deukmejian, then 27, left New York and headed for Los Angeles, mainly because that was where his sister lived.

Deukmejian got his first job working for Texaco in its land and lease department. Soon after, he got a job as a deputy county counsel for Los Angeles County.

At a wedding in 1956, Deukmejian’s sister arranged his introduction to a young Armenian American named Gloria Saatjian, a Los Angeles art school graduate. They were married six months later.

The couple moved to Long Beach in 1958, and Deukmejian opened a law office. One of his law partners was Malcolm Lucas, whom Deukmejian years later named as chief justice of the California Supreme Court.

In Long Beach, the politically ambitious Deukmejian became involved in a host of civic activities including the Lions Club, the Community Chest, the Red Cross, the Boy Scouts and the Elks. He was named Long Beach “Man of the Year” in 1959.

In 1962, Deukmejian won election to the Assembly after campaigning against crime, communism, big government and what he called “the trend toward socialism.”

Within a month of his arrival in Sacramento, he introduced his first set of crime bills, including one that would have imposed the death penalty for armed robbery. During the 1970s, he led a successful fight to restore the death penalty in California, which had been struck down by the state Supreme Court. He was a strong opponent of reducing penalties for marijuana possession.

Deukmejian spent four years in the Assembly before moving on to the state Senate in 1966, where he served 12 years.

In 1970, Deukmejian announced his candidacy for attorney general, running on a platform of greater protection and security for people. He finished a distant fourth out of four candidates in the Republican primary.

Deukmejian finally met with success in 1978, when he won the GOP nomination for attorney general and went on to beat Democrat Yvonne Brathwaite Burke in the general election, again campaigning on a law-and-order platform.

As attorney general from 1979 to 1982, Deukmejian maintained a high profile as a crime fighter. On one well-publicized occasion, he donned a flak jacket and accompanied police officers as they raided marijuana fields in Northern California.

But Deukmejian had set his sights on the governor’s office, and his chance came in 1982 when he squeaked by Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley. He would defeat Bradley again in a 1986 rematch.

When Deukmejian first went to Sacramento as governor, he inherited a $1.5-billion budget crisis from his predecessor, Brown. Setting the tone for the remainder of his administration, Deukmejian immediately took a stern line with the Legislature and opposed raising what he called “general taxes.” Before the year was out, an upsurge in the economy erased the deficit, a stroke of luck that gave the new governor a significant political boost.

Deukmejian’s two terms were replete with fights with the K-12 education community. Schools advocates became so frustrated that, in 1988 they succeeded in getting voter approval for Proposition 98, which reserved the bulk of state budget spending for K-12 education and community colleges.

Deukmejian also got into a bitter name-calling fight with state Superintendent of Public Instruction Bill Hoenig over school funding. Both were left tarnished.

During his two terms, the governor rejected about $7 billion in spending proposed by the Legislature, much of it in health, welfare and education programs. In all, he vetoed 2,298 bills — a sixth of those that came before him from the Democratic-controlled Legislature — earning him the nickname “Governor No.” None of his vetoes were overridden.

One of Deukmejian’s biggest successes as governor came on the issue of transportation.

Although he had previously resisted working with legislative leaders, during his second term he finally opened the door to limited negotiating with key Assembly and Senate leaders in order to devise an $18.5-billion, 10-year transportation improvement plan — financed mostly by a 9-cents-per-gallon gas tax increase — which voters later endorsed.

Democrat Gray Davis, then the state’s controller, called the measure “the most significant piece of legislation to pass on [Deukmejian’s] watch” and said that Deukmejian could thus “claim to have contributed significantly to California’s transportation future.”

Among Deukmejian’s other major legislative accomplishment was a landmark program that required welfare recipients to undergo job training and perform community-service work in exchange for their checks. He also worked out a deal with Democratic legislative leaders that led the way toward making California the first state to ban military-style assault weapons.

The weapons ban was a surprising turn for a Republican politician who had in the past opposed gun controls. It came after a drifter named Patrick Purdy killed five children in a crowded Stockton schoolyard with an AK-47 rifle on Jan. 17, 1989. Deukmejian responded in a way that sent a shudder through many members of his own party as well as the gun lobby, which had until then met with nothing but success in warding off gun controls. He said that he did not see “any reason why anybody has to or needs to have a military assault-type weapon, even somebody who is a sportsman or a hunter.”

Sumner Offill, one of Deukmejian’s earliest supporters, recalled an occasion after Deukmejian left office when the governor was asked at a symposium in the state Senate chamber what he thought were the toughest issues he faced in governing the state.

“He said the toughest moments didn’t have to do with the budget crises or any big political battles,” Offill said. “He said the toughest moments he had were when he met the wives and children of the law enforcement people who had been killed in the line of duty.”

With that disclosure, Deukmejian choked up, holding back sobs. News reports at the time said that the Senate chamber became very still.

“It showed me who he was, the depth of his identification and commitment to those who gave of themselves, and it was really something to see,” Offill said. “To have the ‘Iron Duke’ become so emotional was really quite a moment.”

Deukmejian was long seen as a senior statesman in Republican politics, quietly advising potential candidates. He appeared on a number of panels with the state’s other former governors — most frequently his successor, Pete Wilson. A state courthouse named in his honor opened in Long Beach in 2013. That same year, he joined the former governors in filing a lawsuit against federal efforts to force the state to reduce its prison population.

In addition to his wife, Gloria, Deukmejian is survived by his daughters, Leslie Gebb and Andrea Pollak; and his son, George Deukmejian, Jr.

Luther and Paddock are former Los Angeles Times staff writers.

Times staff writer John Myers contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

6:10 p.m.: This article has been updated with additional quotes and information on survivors.

This article was originally published at 4 p.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.