Russell Means dies at 72; American Indian rights activist, actor

- Share via

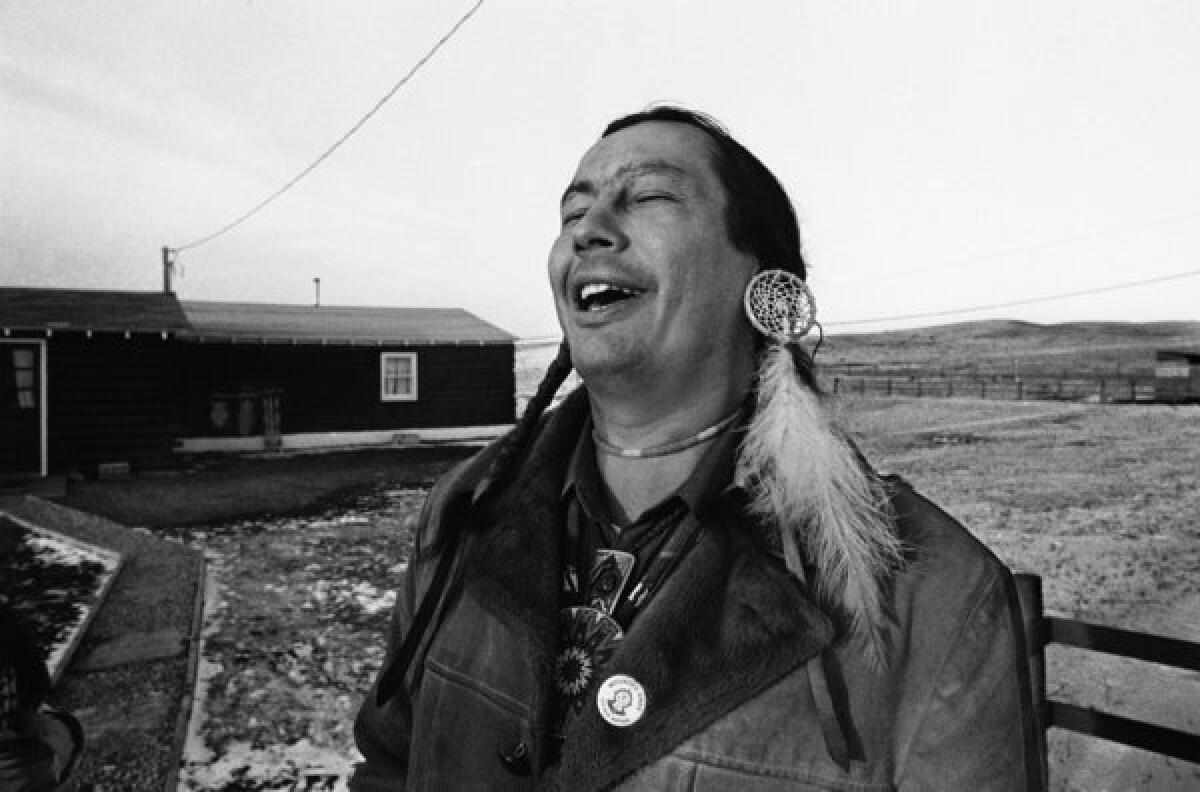

Russell Means, who gained international notoriety as one of the leaders of the 71-day armed occupation of Wounded Knee in South Dakota in 1973 and continued to be an outspoken champion of American Indian rights after launching a career as an actor in films and television in the 1990s, has died. He was 72.

Means died Monday at his home in Porcupine, S.D., on the Pine Ridge Reservation, said Glenn Morris, his legal representative.

Diagnosed with esophageal cancer in July 2011 and told that it had spread too far for surgery, Means refused to undergo heavy doses of radiation and chemotherapy. Instead, he reportedly battled the disease with traditional native remedies and received treatments at an alternative cancer center in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“I’m not going to argue with the Great Mystery,” he told the Rapid City Journal in August 2011. “Lakota belief is that death is a change of worlds. And I believe like my dad believed. When it’s my time to go, it’s my time to go.”

Means had been declared cancer-free in April but suffered a recurrence of the disease in his lungs and died after contracting pneumonia, Morris said.

The nation’s most visible American Indian activist, Means was a passionate militant leader who helped thrust the historic and ongoing plight of Native Americans into the national spotlight.

In joining the fledgling American Indian Movement in 1969, Means later wrote, he had found a new purpose in life and vowed to “get in the white man’s face until he gave me and my people our just due.”

An Oglala Sioux born on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, Means in his activist prime was called strident, defiant, volatile, arrogant and aggressive. He was frequently arrested and claimed to have been the target of numerous assassination attempts.

A onetime con artist, dance-school instructor and computer programmer, Means was executive director of the government-funded Cleveland American Indian Center when he met Dennis Banks and other AIM founders in 1969.

In joining the American Indian Movement at age 30, Means later wrote in his autobiography, he had found “a way to be a real Indian.”

In Cleveland, he founded the first AIM chapter outside Minneapolis, and he became the organization’s first national coordinator in 1971.

In 1970, he was among a group of American Indian activists who occupied Mount Rushmore, where he infamously urinated on the top of the stone head of George Washington — an act he later said symbolized “how most Indians feel about the faces chiseled out of our holy land.”

That November, he joined fellow AIM members and other Native Americans in taking over a replica of the Mayflower in Plymouth, Mass. And in 1972 he participated in the seven-day occupation and trashing of the Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters in Washington, D.C.

But the controversial and flamboyant activist with the trademark long braids gained his greatest notoriety at the trading post hamlet of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

The occupation of Wounded Knee by more than 200 AIM-led activists began in late February 1973 in the wake of a failed attempt to impeach tribal president Richard Wilson, whose Oglala critics accused him of corruption and abuse of power and said his private militia suppressed political opponents.

After the takeover of Wounded Knee, the historic site of the 7th Cavalry’s large-scale massacre of Sioux men, women and children in 1890, the area was cordoned off by about 300 U.S. marshals and FBI agents, who were armed with automatic weapons and aided by nine armored personnel carriers.

Among the occupiers’ demands were that congressional hearings be held to protect historical benefits held in trust by the U.S. government.

Before the occupation ended peacefully in May, two occupiers were dead and a U.S. marshal, who was paralyzed from the waist down, was among the wounded.

A federal grand jury reportedly indicted 89 people, including several AIM leaders, for federal crimes in connection with the seizure and occupation of Wounded Knee.

That included Means and Banks, who emerged, as a 1986 story in The Times put it, as “the two most famous Indians since Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse wiped out Custer nearly a century earlier.”

Their widely publicized trial in 1974 on a variety of felony charges ended after eight months when a federal judge threw out the case on grounds of prosecutorial misconduct.

On the 20th anniversary of the occupation in 1993, former South Dakota Gov. Bill Janklow told the Associated Press that the fighting intensified racism, bitterness and fear in the state.

Means saw it differently, saying it was the Indians’ “finest hour.”

“Wounded Knee restored our dignity and pride as a people,” he told the Minneapolis Star Tribune in 2002. “It sparked a cultural renaissance, a spiritual revolution that grounded us.”

Tim Giago, the retired editor and publisher of the Native Sun News in Rapid City, S.D., takes a critical view of Means’ militant methods as an activist.

“I think he could have accomplished 10 times what he did eventually accomplish, which was to bring focus on Native American issues, if he had followed the path of Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi instead of turning to violence and guns,” Giago, who was born and raised on the Pine Ridge Reservation, told The Times last year.

“If he had followed a peaceful demonstration like those two great leaders did, I think he would have had much more support from the American people that I think he lost when he turned to violence,” Giago said. “As a matter of fact, he lost the support of a lot of Native Americans when he resorted to violence.”

Historian Herbert T. Hoover, a professor emeritus at the University of South Dakota whose specialties include the history of American Indian-white relations in Sioux Country, described Means as “a force for good during the civil rights movement on behalf of American Indians.”

“I don’t think Russell should be remembered as a radical,” Hoover told The Times in 2011. “Russell was somebody who simply wanted Indians to get their due in the civil rights period.”

Means’ 1974 trial wasn’t the end of his legal troubles.

In 1976, he was acquitted of a charge of murder in the 1975 shooting death of a 28-year-old man at a bar in Scenic, S.D. He had been accused of aiding and abetting in the shooting for which another man was convicted of murder.

And in 1978, Means began a one-year prison term after being convicted of an obstruction of justice charge related to a 1974 riot between American Indian Movement supporters and police at the courthouse in Sioux Falls, S.D.

Through it all, he continued his high-profile activism.

In Geneva in 1977, he was a delegate to the “Conference on Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations of the Americas.” As one of the main speakers, he urged the conference to recommend Indian participation in the United Nations and attacked the U.S. government.

“We live in the belly of the monster,” he said, “and the monster is the United States of America.”

In the mid-1980s, Means spent several weeks in the jungles of Nicaragua with the Miskito Indians in an attempt save them from what he said was “an extermination order” issued by Daniel Ortega’s Sandinista government.

Means also tried his hand at national politics in the ‘80s.

In an attempt to bring the “world view of the Indian” to the American people, he agreed in 1983 to be Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt’s running mate in Flynt’s unsuccessful campaign for the presidency of the United States.

And in 1987, Means sought the presidential nomination of the Libertarian Party but lost to former Texas Congressman Ron Paul.

Means’ acting career began after he was approached by a casting director to play Chingachgook in the 1992 movie “The Last of the Mohicans.”

A string of more than 30 other roles in films and television followed, including playing a shaman in “Natural Born Killers” and providing the voice of the title character’s father in “Pocahontas.”

Means’ transition from activist to actor was deemed a natural one.

“Russell has always been very mediagenic,” Hanay Geiogamah, who joined AIM in 1971 and co-produced a series of Native American TV movies on TNT, told The Times in 1995. “He was eloquent, capable of synthesizing complex political ideas for the press and, with his long black braids and statuesque physique, the image the media wanted to see.

“Russell was smart enough to realize that when you’ve got it, you’ve got it. He used the system … and used it well.”

Oliver Stone, who directed Means in “Natural Born Killers,” described him as “a renegade with one foot in both corrals, someone who has walked a crooked and strange life.”

“He’s a very authoritative presence with his own brand of magic,” Stone told The Times in 1995. “Whether he’s acting or not is hard to say.”

Of his career as an actor, Means told The Times in 1995: “I haven’t abandoned the movement for Hollywood. … I’ve just added Hollywood to the movement.”

As he told the Washington Post a year later, “My life has been a life of passion, and I’m still a voice for traditional Indian people, for freedom-seeking Indian people.”

Means was born Nov. 10, 1939, on the Pine Ridge Reservation. After his father landed a job in a Navy shipyard during World War II, the family moved to Vallejo, Calif., in 1942. Summers, Means would return to South Dakota to visit relatives on the reservations.

Means, who chronicled his life in the 1995 book “Where White Men Fear to Tread” (written with Marvin J. Wolf), continued his activism in old age.

In 2007, he was among some 80 protesters who were arrested after blocking Denver’s Columbus Day parade honoring Christopher Columbus, an event they condemned for being a “celebration of genocide.”

Asked if he was still active in the American Indian Movement in an interview in the Progressive in 2001, Means said, “As far as I’m concerned, as long as I’m alive, I’m AIM.

“We were a revolutionary, militant organization whose purpose was spirituality first, and that’s how I want to be remembered. I don’t want to be remembered as an activist; I want to be remembered as an American Indian patriot.”

Means is survived by his fifth wife, Pearl Daniels Means, and several children.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.