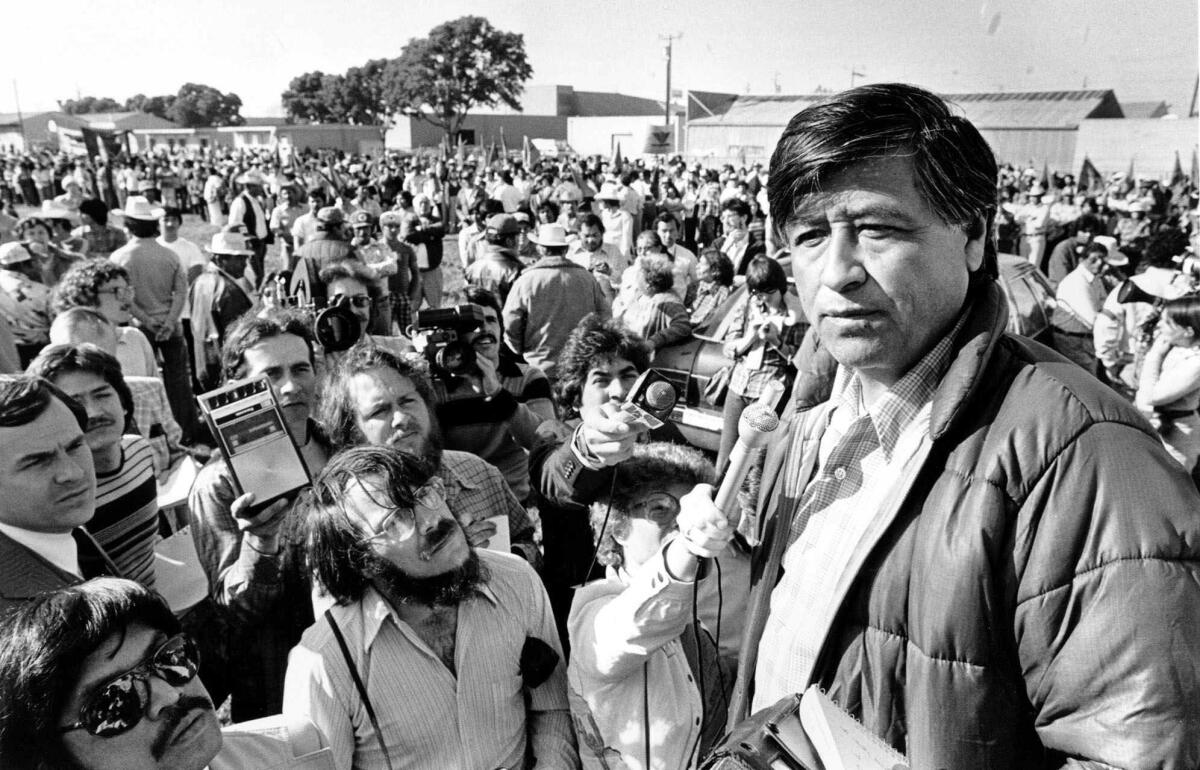

From the Archives: Cesar Chavez, founder of the UFW, dies at 66

- Share via

Cesar Chavez, who organized the United Farm Workers union, staged a massive grape boycott in the late 1960s to dramatize the plight of America’s poor farmhands, and later became a Gandhi-like leader to urban Mexican-Americans, was found dead Friday in San Luis, Ariz., police said. He was 66.

Authorities in San Luis, a small farming town on the Mexican border about 25 miles south of Chavez’s native Yuma, said the legendary farm workers’ leader apparently died in his sleep at the home of a family friend.

“He was our Gandhi,” said Democratic state Sen. Art Torres, a prominent Chicano politician from Los Angeles’ Eastside, upon hearing news of Chavez’s death. “He was our Dr. Martin Luther King.

“It’s hard to find people like him who epitomized the spiritual and political goals of a people.”

President Clinton said in Washington, “The labor movement and all Americans have lost a great leader with the death of Cesar Chavez. An inspiring fighter for the cause to which he dedicated his life, Cesar Chavez was an authentic hero to millions of people throughout the world.”

Indeed, to many, America’s quest for equality for its ethnic and racial minorities had largely been framed in terms of black and white. Mexican-Americans, and Latinos in general, were largely ignored by politicians except at election time.

That changed when Chavez, the son of migrant farm workers, became the head of the UFW in 1965.

A dedicated advocate of nonviolence, Chavez galvanized public support on behalf of farm workers, many of them illegal immigrants who averaged as little as $1,350 a year in the farm industry that at the time grossed $4 billion annually. Workers lived in substandard housing.

The early struggles in the San Joaquin Valley were marked by bitter and sometimes brutal incidents involving picketing farm workers who screamed “ Huelga! “ -- “Strike!”--and growers who vowed never to give in to Chavez and his followers.

Chavez’s greatest achievement was the 1968 boycott of California grapes. Beginning in the spring, more than 200 union supporters, many of them earning $5 a week for their help, fanned out across the United States and Canada to urge consumers not to buy grapes.

The mayors of New York, Boston, Detroit and St. Louis directed their purchasing agents not to buy non-union grapes. In Cleveland, Mayor Carl B. Stokes encouraged major grocery stores to prominently display the UFW symbol, the black Aztec eagle, to encourage shoppers to observe the boycott. A 300-mile march from Delano to the Capitol in Sacramento was an emotional high point for the cause.

By August, California growers estimated that the boycott had cost them about 20% of their revenue.

At times, the struggle looked especially bleak to Chavez when he had to beg for food for his wife and eight children from the very farm workers he sought to help.

“It turned out to be about the best thing I could have done,” he would say later, “although it’s hard on your pride. Some of our best members came in that way. If people give you their food, they’ll give you their hearts.”

He caught the attention of national figures, including U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, who sought the Democratic Party nomination for President before his assassination in 1968. The New York senator called the soft-spoken Chicano “one of the heroic figures of our times.”

In addition to the boycotts he mounted, Chavez also used a series of fasts to rally support, including a 36-day, water-only fast in 1988 that severely affected his health.

At its peak in the 1970s, the UFW said that about 70,000 workers in California’s fields were covered by its collective bargaining agreements.

In focusing attention on migrant workers, Chavez also helped millions of urban Mexican-Americans who were chafing for more educational opportunities, better housing and more political power.

El Movimiento, the Chicano civil rights campaign of the late 1960s, was characterized in many barrios such as East Los Angeles by marches opposing the Vietnam War and supporting the UFW.

By the 1980s, however, the union lost the earlier gains and Chavez found less and less public enthusiasm and support for boycotts. Union membership dipped to below 10,000. Many of the detractors in recent years called him an irrelevant force in today’s labor and political situations.

Nevertheless, he was remembered Friday as a giant in the civil rights movement of the United States.

U.S. Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.) said that Chavez “was one of the great pioneers for civil rights and human rights of our century.”

“His tireless commitment to improve the plight of farm workers profoundly touched the conscience of America and inspired millions of others to work for justice in their own communities,” Kennedy said in a statement released by his Washington office.

Lane Kirkland, president of the AFL-CIO, said Chavez was instrumental in organized labor’s efforts to improve the lot of the rank and file.

“Always, Cesar conveyed hope and determination, especially to minority workers, in the daily struggle against injustice and hardship,” Kirkland said in a statement. “The improved lives of millions of farm workers and their families will endure as a testimonial to Cesar and his life’s work.”

Los Angeles County Supervisor Gloria Molina called Chavez a “man of dignity, a man of honor.”

But, perhaps, the most touching tribute came from an Orange County political activist.

“We just lost Cantinflas, now Chavez. This is truly a sad day for Latinos,” said Rueben Martinez, who lives in Santa Ana. “Cesar was a very humble person.”

Growers who opposed Chavez’s efforts were downplaying his role in California’s burgeoning agribusiness industry.

“I think his legacy is very little,” said grower John Giumarra of the San Joaquin Valley community area of Arvin. “He built this organization which failed ultimately because it wasn’t a union. It wasn’t oriented toward the needs of farm workers.”

Chavez had returned to the southwest corner of Arizona, where he grew up, to visit with friends and fight a lawsuit filed against the union, said San Luis Mayor Tony Reyes.

He had been staying in the home of a family friend, Dona Maria Hau , for the past week. He was found dead shortly after 9 a.m. Friday. Hau and a UFW official said Chavez had been fasting during his stay there, but they persuaded him to eat a vegetarian meal Thursday night out of concern for his health.

As word of his death spread, farm workers throughout California expressed shock and disbelief.

Lettuce cutters and vegetable pickers from throughout the Salinas Valley began arriving at the UFW office in Salinas upon hearing the news. Workers, wearing their work boots still muddy from the fields, burst into tears when they arrived at the office. Others simply prayed beneath a large picture of the Virgin Mary, with a smaller picture of Chavez underneath.

“The workers have been coming in by the dozens, all day long,” said Martin Vasquez, grievance coordinator for the UFW. “They all feel that even though he is gone, his ideas live on.”

Dolores Huerta, the longtime UFW vice president, had to sit down when she was told the news of Chavez’s death.

“We’re in a state of shock,” she said. “His mother was 99 when she died. His father was 101. All of his family has longevity. So no one ever anticipated Cesar having an early death. We all thought he’d live into his 90s.”

Former Gov. Edmund G. (Jerry) Brown Jr. first met Cesar Chavez in 1966 and stayed in touch with him until his death.

“I remember the first time I saw him. He walked into my father’s house in Hancock Park and he was dressed the same way as when I saw him a month ago. He never lost his modesty and simplicity.

“Cesar wasn’t afraid of anybody. He was a real fighter. The farmers were scared to death of him. Politicians in the (San Joaquin) Valley wouldn’t stand next to him.”

Cardinal Roger Mahony, archbishop of Los Angeles, said he was “deeply saddened to learn of the death of Cesar Chavez, a tireless champion in the struggle for the recognition of and respect for the human rights and dignity of agricultural workers here in California as well as throughout the United States.

“His commitment, deeply rooted in his Catholic faith and inspired by the Gospel and the church’s social teachings, drew untold thousands to the cause of justice he espoused.”

Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari also paid tribute to Chavez, calling him a “dedicated man who worked very hard for Mexican-American farm workers and Mexican migrants.”

One of five children, Chavez was born on March 31, 1927, on a small farm near Yuma. The Depression shattered his father’s finances when young Chavez was 10, and the family took to the roads as migrant laborers.

He never graduated from high school, and once said he went to as many as 65 elementary schools because of the family’s constant search for work in the fields. He said his mother taught him to be humane while living in often inhumane conditions.

“She sent us to invite hobos to share our tortillas and beans,” he told one interviewer.

At an early age, Chavez heard talk of union organizing.

“About 1939,” Chavez recalled in an interview, “we were living in San Jose. One of the old CIO unions began organizing workers in the dried-fruit industry, so my father and uncle became members. Sometimes the men would meet at our house and I remember seeing their picket signs and hearing them talk.

“They had a strike, and my father and uncle picketed all night. It made a deep impression on me.”

The strike ultimately failed but Chavez had become an ardent unionist.

During World War II, in 1944 and 1945, Chavez served in the Navy. After the war, he returned to organizing efforts and met his wife, Helen, while working in the field in Delano, in the rich, flat plains of Kern County.

In 1952, Chavez lived in San Jose’s Mexican-American barrio of Salsipuedes—which means “‘Get out if you can”—when he met Fred Ross, a community organizer who wanted to set up self-help groups in minority areas.

Ross had heard of Chavez and sought him out. “He looked to me like potentially the best grass-roots leader I’d ever run into,” Ross recalled later.

In 10 years with the group, Chavez led a successful voter registration drive in San Jose. He took up the cases of hundreds of Mexican-Americans and Mexican immigrants who complained of mistreatment by police, immigration authorities and welfare officials.

In 1962, he left to establish the National Farm Workers Assn., which later would become the UFW, an affiliate of the AFL-CIO.

In the late 1970s, the UFW was at its peak.

Chavez, using marches, boycotts, strikes and civil disobedience by followers, had the power to force growers in California’s agricultural valleys to the bargaining table. The UFW won tremendous wage increases and extensive benefits for workers and defeated the powerful Teamsters Union in several battles for contracts.

Even non-union workers were being paid above minimum wage because of the UFW’s influence. For the first time, many California farm workers were covered by medical insurance, no longer labored over back-breaking, short-handled hoes and had fringe benefits on a par with workers in other industries.

“He was the first person to organize farm labor on a large scale . . . in that sense he was the most important labor leader since World War II,” Jerry Brown said.

“He really represented the basic division between the power structure and the people at the bottom who speak a different language and have a different skin color.”

Chavez’s accomplishments, using nonviolence, were comparable to what Martin Luther King Jr. accomplished during the civil rights movement, said Jerry Cohen, general counsel for the UFW from 1967 to 1981.

“Those were great years,” Cohen said. “Cesar accomplished more with fewer people than anyone I know of. . . . He was like water running downhill at that time. Nothing could stop us.”

The UFW’s influence began to wane in the early 1980s, and many of the gains have vanished. The pay of workers has dropped, fewer workers belong to unions and the housing for many workers has turned abysmal.

The Salinas Valley, once a union stronghold, is an example of how far the union has fallen. The union only has one contract left among vegetable growers in the area, where it once had about 35.

During the decline, the union suffered considerable internal strife, and growers became more sophisticated in their battles with the union. The oversupply of workers during the 1980s, labor experts say, also hurt recruiting.

Chavez determined that the union could not organize workers and hold elections in such a politically hostile environment. So he switched tactics, turning to boycotts instead of focusing the union on organizing workers. The decision was widely criticized and caused a split among UFW members.

Despite his position with the union, Chavez maintained an austere lifestyle. As recently as the late 1980s, he did not own a house or a car and estimated his total income at $900 a month—the same as other union organizers.

Chavez is survived by his wife and eight children, three of whom work for the UFW. Funeral services were incomplete.

Times staff writers Miles Corwin in Los Angeles, Mark Arax in Fresno, David Avila in Costa Mesa, Juanita Darling in Mexico City and Tony Perry in San Luis, Ariz., contributed to this story.

--

--

Cesar Chavez, 1927-1993

‘There is no life apart from the union. It is totally fulfilling.’

1927: Born March 31 on a small farm near Yuma, Ariz.

1939: When the family loses its farm in the Depression, they become migrant laborers.

1962: Chavez begins organizing pickers into what later becomes the United Farm Workers union.

1965: The fledgling union strikes table-grape growers in Delano in the San Joaquin Valley.

1968: Chavez fasts for 25 days to call attention to “the pain and suffering of the farm workers.”

1970: After a five-year strike and successful grape boycott, the union signs contracts with growers.

1975: Following Teamsters’ attempts to sign up farm workers, legislation guaranteeing farm workers’ secret ballots in union elections passes the California Legislature and becomes law.

1988: Chavez fasts for 36 days to protest the use of agricultural pesticides. It was the only fast that severely affected his health.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.