Before deadly Oakland fire, Ghost Ship warehouse was scene of legal sparring and tenant drama

- Share via

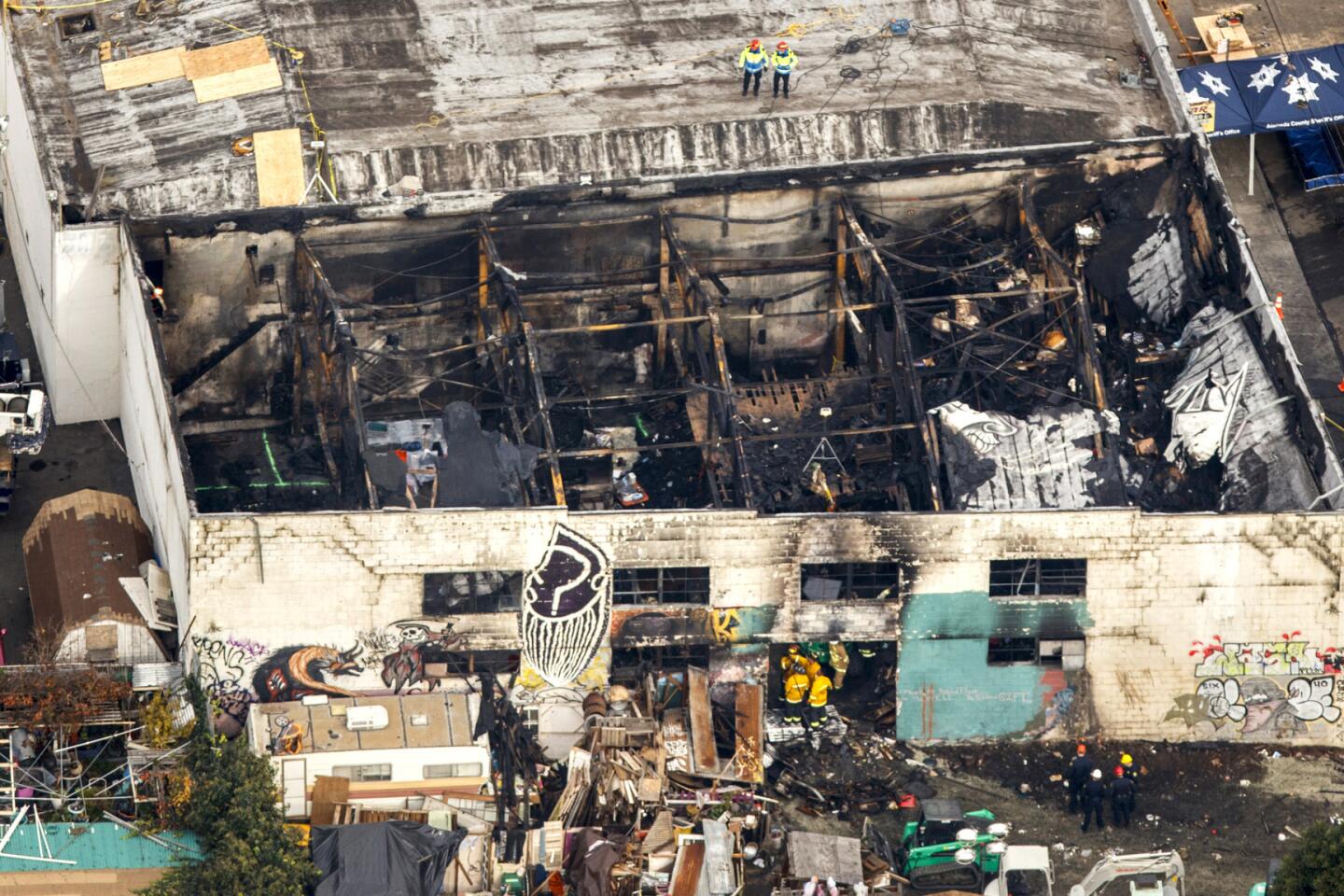

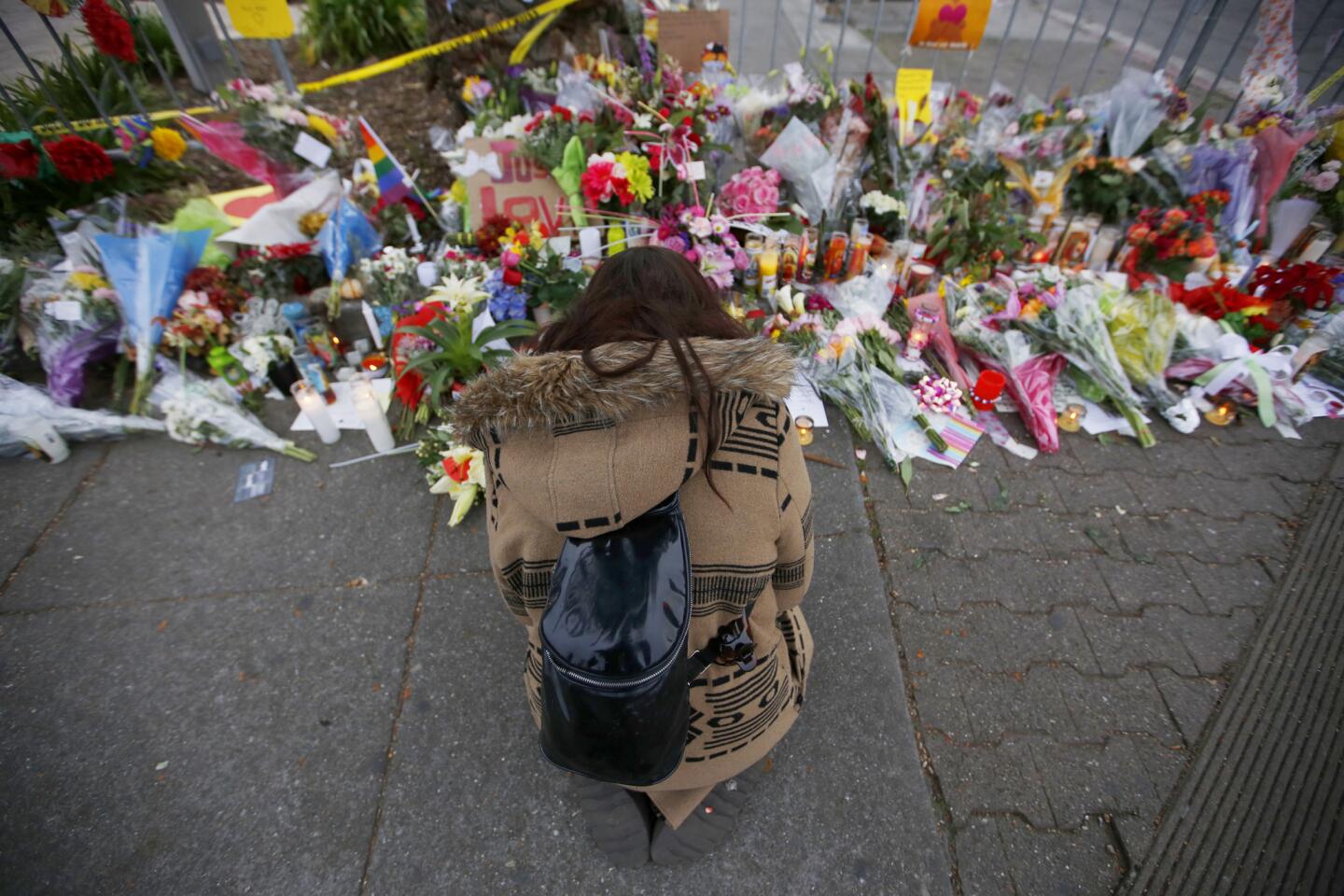

For more than two years, the gray converted warehouse — where a massive fire killed at least 36 people Friday night — had been on Oakland officials’ radar.

Neighbors had complained about piles of trash and illegal construction. A steady stream of young artists came and went, giving every indication that the building was their home, yet the property’s owner had only a permit for a warehouse, not a residence. Officials had opened an investigation into possible code violations and an inspector had visited the warehouse but never went inside.

“The administration has to tell us, well, what happened to the code inspector. Why did he just knock on the door and not pursue?” said City Councilman Noel Gallo, whose council district includes the Fruitvale neighborhood, where the warehouse was located. “This thing has been going on for 2 1/2 years.”

The city of Oakland has yet to release a full accounting of all city building or fire code inspections and investigations of the warehouse, but city records available online show at least five complaints had been investigated since June 2014.

As searchers continued to look for bodies Monday, there was mounting pressure on city officials to explain how they dealt with all the complaints and whether safety problems were ignored.

The warehouse was a 10,000-square-foot tinderbox with stacks of discarded furniture piled high, a rickety staircase made partly of wooden pallets, and a half-dozen RVs. Officials said they have found no evidence of sprinklers or fire alarms inside the structure, known as the Ghost Ship. And, according to the man who oversaw the building, it was also outfitted with his homemade electrical repairs, which he did not obtain permits for. Derick Almena told NBC News on Monday that he made those repairs because the landlord refused.

Chor N. Ng, the warehouse owner, could not be reached for comment. Her daughter, Eva Ng, has previously said the family was unaware people were living there.

Zac Unger, vice president of the local Oakland Firefighter Union, said the fire marshal’s inspection unit has been understaffed for years.

“We’re way short, especially in an aging city with a huge amount of building going on,” Unger said.

Unger said a more aggressive fire marshal’s office would scour the city looking for buildings that avoided scrutiny in the past, or had other city code violations, and might be hazardous. Such tactics could have possibly prevented the tragedy at the warehouse, he said.

If the fire is determined to be an arson, prosecutors could bring murder or aggravated arson charges — with one count for each person killed.

“Had a fire inspector walked into that building and seen the conditions in there, they would have shut the place down,” Unger said.

Alameda County Dist. Atty. Nancy O’Malley said her office is investigating the fire, which torched the building during an unpermitted concert. The probe could result in criminal charges, including murder or manslaughter, she said.

Responding to questions about the city’s handling of the warehouse complaints, Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf said in a statement the city will provide more information about the matter.

“We recognize people deserve answers. While we have all hands on deck to appropriately focus on safe recovery of victims, care of their families and preservation of evidence for investigations, we have had initial information compiled and will be reviewing it with the District Attorney prior to release,” Schaaf said.

Buildings like the Ghost Ship are all too common in Oakland, where the constant pressure of rising real estate values in the Bay Area has pushed artists and musicians into illegal housing and discouraged them from reporting substandard conditions.

In this particular case, the building was leased to the Satya Yuga Collective, operated by Almena. According to those who lived there, Almena collected the rent and lived in the warehouse with his wife, Micah Allison, and their three young children.

Almena and Allison’s reign over the warehouse was filled with drama and legal sparring with tenants and partygoers.

After an erotic-themed New Years Eve party in 2014 — the warehouse’s “twisted stairways,” “hidden coves” and secret nooks strewn with pillows and blankets were billed as attractions — a San Francisco event producer, Philippe Lewis, returned to retrieve his sound equipment, according to court records. He was confronted by Almena, who was angry because his toddler son had found a condom after the party.

“I explained things like that can happen at a large party,” Lewis later told police, according to records.

A shoving match ensued, in which Lewis said he was scratched and his shirt was torn, and a friend who was with him said his arm was pulled out of its socket. The responding Oakland police officer wrote in his report that he canvassed the building as part of his investigation; but if he noticed unsafe living conditions or a do-it-yourself electrical set-up, he made no mention of them. From the records, it does not appear any arrests were made.

In a subsequent request for a restraining order against Almena, Lewis said Almena threatened to get a gun during the altercation and noted that there were “a number of bows and arrows” and a box of bullets on display in the warehouse, adding a dash of authenticity to the alleged threat.

“I am afraid this person might be unstable,” Lewis wrote on the form, which he signed Jan. 6, 2015.

Less than month later, Almena filed his own request for a restraining order. His target was a tenant, Shelley Mack, who he said refused to pay rent and was physically and verbally abusive.

Mack, 58, told The Times that in the winter of 2014 she paid $700 a month to live inside a trailer parked in the warehouse. She had been drawn to the space by a Craigslist ad promising cheap rent. Once there, she and several tenants — between 10 and 20, depending on the day — shared a single bathroom. The building had no heat, and in November 2014 a transformer blew, cutting off power.

“There was no electricity, and it was freezing in there,” she said.

Gas-powered generators were used to run small space heaters, and propane tanks placed indoor by the exits fueled other heaters, Mack said. In photographs she took at the time, electrical cords can be seen snaking through the building. She said she called the Oakland Police Department multiple times to complain.

Almena said Mack tormented him and his family. During one altercation, Almena said one of Mack’s associates pulled a gun and chased him with it while Mack “robbed personal property,” according his request for a restraining order.

Almena said Mack also repeatedly called child protective services with false accusations aimed at having his children taken away.

Alameda County Social Services removed Almena’s children, then ages 11, 6, and 4, in March 2015, court records show. The reasons for the removal were not clear from the records.

Earlier this year, Almena’s wife posted photos on her Facebook page showing the family reunited.

Mack, who said she was never served with Almena’s complaint, denied the allegations Monday night.

Neither Almena nor Allison could be reached for comment by The Times.

Some in Oakland’s arts scene said they feared the city would respond to the fire by cracking down on illegal living arrangements and evicting tenants. To forestall this possibility, some talked about reaching out to contractors who could help bring converted industrial buildings up to code without drawing the scrutiny of city inspectors.

On Monday, Gui Cavalcanti, who opened an artist studio space in Massachusetts and briefly lived in a warehouse, posted a guide online advising people living in artistic communities like the Ghost Ship to make sure their buildings had enough emergency exits and smoke detectors.

From his perspective, the fire and the building conditions that fed it are partly due to the Bay Area’s housing market, and the fact that artists often seek out spaces in which they can live and work and design their surroundings as they please. Cavalcanti also attributed the tragedy to landlords’ desire to own multiple properties and lease them out without having to police them too carefully.

“I could go on Craigslist right now and find some landlord who’s renting out a 3,000-square-foot space and be like, ‘I’ll sign this document and pay you cash, just give me the space.’ That’s the environment we’re in,” he said.

“It is absolutely not just Oakland; it is every major city,” he said. “I’m sure L.A. has hundreds of these buildings.”

Times staff writers Soumya Karlamangla and Veronica Rocha contributed to this report.

ALSO

Who could be held responsible for the Oakland fire

When loved ones couldn’t track those missing in Oakland fire, they found answers on social media

Oakland warehouse had hosted parties, despite safety concerns of former residents

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.