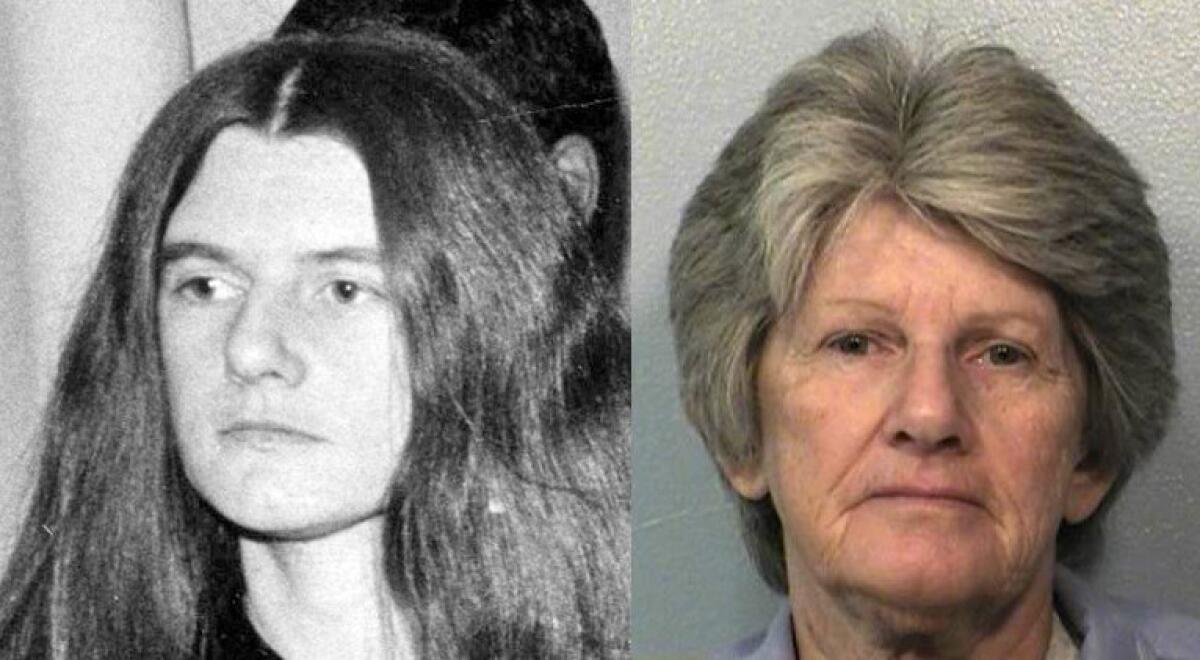

Manson follower Patricia Krenwinkel’s bid for freedom denied, despite claims he abused her

Krenwinkel is a former member of the so-called Manson family, currently serving life in prison. (Dec. 29, 2016)

- Share via

The decision is the latest in a long series of repeated denials by Krenwinkel to secure parole on her conviction in a murderous rampage with Manson and other so-called Manson family members. But late last year, her attorney asserted new claims that Krenwinkel suffered abuse at Manson’s hands before the murders.

A Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation spokesman said Krenwinkel will be eligible to apply for parole again in five years.

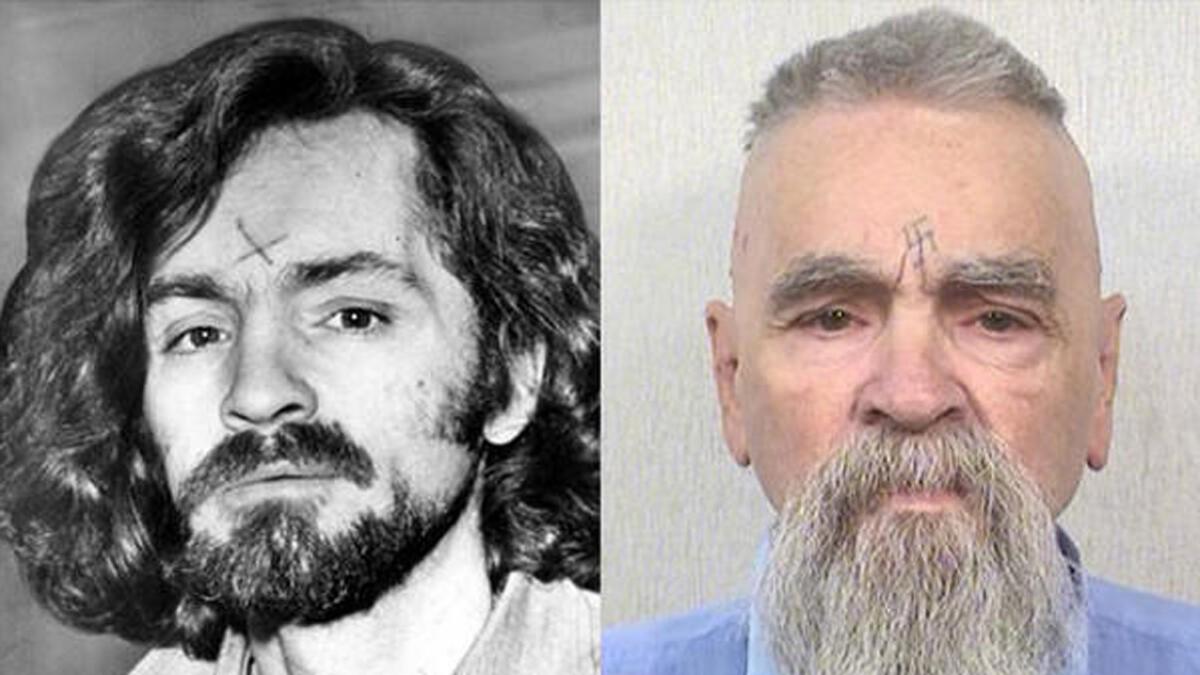

Where are they now? Charles Manson's family, four decades after horrific murders »

Here’s a breakdown of the case:

THE CRIME

A murderous rampage

On Aug. 9, 1969, Krenwinkel joined the band of Manson acolytes who stormed the Benedict Canyon home shared by pregnant actress Sharon Tate, 26, and her movie director husband, Roman Polanski. Tate and four others were stabbed and shot. Krenwinkel testified to chasing coffee heiress Abigail Folger with a knife and stabbing her 28 times.

The next night, Krenwinkel and others killed Leno LaBianca and his wife, Rosemary, at their Los Feliz home. Krenwinkel and fellow family member Leslie Van Houten held down Rosemary LaBianca as Charles “Tex” Watson stabbed Leno LaBianca.

Both homes had walls smeared with blood, and Krenwinkel used blood to scrawl the words “Death to Pigs.” She later testified at trial that her hand throbbed from stabbing one of the victims so many times.

THE LEGAL PROCESS

‘The public is in fear’

Krenwinkel was sent to death row in 1971 after a Los Angeles jury convicted her of killing Tate and six others in the two-day rampage.

After the state’s highest court in 1972 ruled the death penalty unconstitutional, Krenwinkel’s sentence — along with those of other Manson family members — was commuted to life in prison with the possibility of parole.

Krenwinkel has sought parole more than a dozen times.

At a 2011 hearing, the panel recognized Krenwinkel’s efforts, commending her for a clean disciplinary record, having earned a bachelor’s degree, and her work training service dogs and counseling fellow inmates.

But Commissioner Susan Melanson said the barbarity of the crimes — coupled with Krenwinkel’s failure to fully grasp the global effects of the Manson killings — warranted more time behind bars.

“This crime remains relevant,” Melanson said. “The public is in fear. And that just is a fact of the crime and the consequences of the crime.”

NEW CLAIMS

Did Manson abuse Krenwinkel?

Last year, Krenwinkel’s attorney made new claims that she had been abused by Manson or another person.

At a hearing in December before the parole board, a source said Krenwinkel’s attorney, Keith Wattley, raised the notion in his closing statement that his client was a victim of “intimate partner battery.”

The claim, the source said, was akin to battered-spouse syndrome, a psychological condition experienced by people who have suffered prolonged physical or emotional abuse by a partner. The syndrome has been used as a legal defense by women charged with killing their husbands.

In an email to The Times, Wattley wrote in December, “I pointed out that there are some things that haven't fully been investigated (believe it or not). Can't really elaborate at this time.”

THE ROAD AHEAD

California’s longest-serving female prisoner

Prosecutors are opposed to Krenwinkel’s freedom.

By law, decisions by the Board of Parole Hearings must be approved by the governor, and Gov. Jerry Brown has already rejected the idea of setting another Manson follower free.

In April, a state review board recommended parole for Leslie Van Houten, who had been convicted of murder.

Brown reversed that decision and a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge later upheld the governor’s reversal, saying there was “some evidence” that Van Houten still presented an unreasonable threat.

Susan Atkins, a former topless dancer who became one of Manson’s closest disciples, died in prison in 2009 at age 61.

After Atkins’ death, Krenwinkel became California’s longest-serving female inmate.

“What a coward that I found myself to be when I look at the situation,” Krenwinkel said in a 2014 interview with the New York Times. “The thing I try to remember sometimes is that what I am today is not what I was at 19.”

For more breaking news, follow us on Twitter: @Matthjourno and @lacrimes

UPDATES:

1:40 p.m.: This article was updated with news of the denial.

This article was originally published at 8:25 a.m.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.