Black and Latino drivers are searched based on less evidence and are more likely to be arrested, Stanford researchers find

- Share via

It is a wrenching question with vast social and political significance: What role does race play when police stop and search motorists?

Stanford University researchers said Monday they have found evidence that black and Latino drivers face a double standard and that police require far less suspicion to search them than their white counterparts.

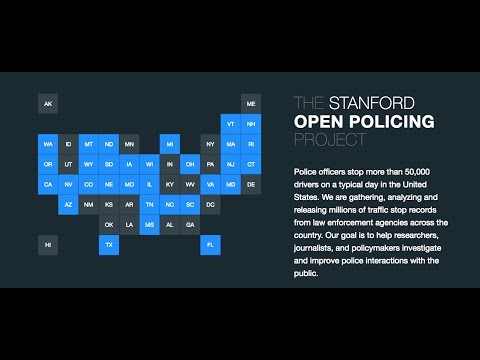

The finding is based on analysis of more than 60 million police stops in 20 states from 2011 to 2015. The database, the largest collection of traffic-stop data ever compiled, was made public Monday by the Stanford Open Policing Project. More than 20 million Americans annually are stopped for traffic violations, according to the study.

Researchers from Stanford’s Computational Journalism Lab and the School of Engineering found that black drivers are generally stopped at a higher rate than white motorists, and Latinos are stopped at a similar or lower rate than whites, after adjusting for age, gender, time and location.

After being stopped, black and Latino drivers are ticketed, searched and arrested more often than whites. For example, when pulled over for speeding, black drivers are 20% more likely than whites and Latino drivers 30% more likely than whites to be ticketed. Black and Latino drivers are about twice as likely to be searched compared with whites.

The findings come as phone and dash cam videos of black and Latino motorists being stopped in violent encounters have filled the airwaves. Images like that of Texas motorist Sandra Bland, an African American who later died in jail, being confronted violently by a state trooper have fueled the debate, according to the study’s authors.

The study found that in Los Angeles County, black drivers are stopped more than whites and Latinos.

For every 100 black drivers, about 15 were pulled over, compared with 10 stops for every 100 white and Latino driver. Black drivers in the county were searched six times per 100 stops; the rate for Latinos was four searches per 100 stops and for whites, two searches per 100 stops.

But researchers noted such disparities alone do not automatically indicate racial bias, but rather could reflect differences in driving behavior and other factors.

So the Stanford group sought to refine their analysis with a test that seeks to answer the question: What level of suspicion must an officer have to search and how does this threshold of suspicion relate to the race or ethnicity of the driver?

Their answer was that blacks and Latinos are searched on the basis of far less evidence than whites.

The threshold test combines information from both the search rates of racial and ethnic groups and the rate at which those searches were successful in finding contraband.

The data “show a clear double standard,” said Cheryl Phillips, a professor of journalism and part of the team.

“When we applied the threshold test to our traffic stop data, we find police require less suspicion to search black and Hispanic drivers than whites. This double standard is evidence of discrimination,” the findings noted.

The threshold test was done with data from nine states. Phillips said some states, including California, did not indicate whether contraband was found during a search, making a correct analysis difficult.

Sharad Goel, assistant professor and leader of the Stanford Law, Order & Algorithms Project, said the researchers are seeking to develop a platform to help understand and improve policing.

Many law enforcement leaders were receptive to the idea.

“Anything that we can use for eliminating bias-based policing we will use,” said Gardena Police Chief Ed Medrano.

Medrano is chairman of California’s Racial and Identity Profiling Advisory Board, established in 2016 to help eliminate profiling in law enforcement. The advisory board is an outgrowth of AB 953, which was signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown in 2015 and requires collection of data on police stops and detentions as well as citizen complaints alleging racial and identity profiling.

The Stanford data could be useful in designing training programs and making other policy changes, said Medrano, who is also president of California Police Chiefs Assn.

And Medrano said he believes AB 953 will ensure that California generates more detailed and accurate data.

In another finding from the Stanford study, researchers found that legalization of recreational use of marijuana in Colorado and Washington in 2012 reduced the total number of searches conducted by police for all racial groups and mitigated some racial disparities.

Twitter: @lacrimes

To read the article in Spanish, click here

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.