Police pursuits cause unnecessary deaths and injuries, L.A. County grand jury says

Nick Phoenix speaks about the death of his teenage son, Jack, who was struck and killed by a stolen car that was fleeing the LAPD in 2015. While police contend they weren’t chasing the car, Phoenix holds the LAPD responsible for his son’s death.

- Share via

Police chases in Los Angeles County are “causing unnecessary bystander injuries and deaths,” and law enforcement officers need better training to reduce the risk of crashes during high-speed pursuits, according to a new report by the county’s civil grand jury.

The report comes after a data analysis by the Los Angeles Times showed that 1 in 10 car chases initiated by the Los Angeles Police Department from 2006 to 2014 resulted in injuries to civilians.

The grand jury said both the LAPD and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department need to improve training for officers who engage in pursuits, and questioned the need to chase suspects for nonviolent crimes. The Sheriff’s Department’s training center is in dire need of an upgrade, the report said.

Citing data provided by the California Highway Patrol, the grand jury report found that 17% of the car chases that took place in the county in a 12-month period beginning in October 2015 ended in a crash that could have resulted in injury or death. Two-thirds of those 421 pursuits ended in an arrest.

Over the same period, three fleeing drivers were killed and 45 people were injured, including suspects, their passengers or officers, the report said.

“Is this the best balance that can be realized between law enforcement goals and the risk of unintended consequences?” the grand jury report asked.

The report also cited a national study conducted by the International Assn. of Chiefs of Police that found that 91% of high-speed chases were initiated in response to nonviolent crimes. The study, which reviewed about 8,000 car chases, found that 42% of the pursuits involved a traffic infraction. A third of the chases were initiated after officers either noticed a stolen vehicle or suspected a driver of being intoxicated, the report said.

L.A. County Sheriff’s Capt. Scott Gage, who oversees training for the agency, agreed with the report’s assessment that deputies should spend more hours training for the dangers of a high-speed pursuit. The agency has allocated funding for a new training facility and is waiting for a bid process to play out to begin construction, Gage said.

The Sheriff’s Department has been involved in 318 pursuits in 2017, according to data released this week by the agency. Those chases resulted in the death of one civilian and injuries to nine others, records show.

In a statement, the LAPD said pursuits are “inherently dangerous and that is why the Los Angeles Police Department takes every step to develop tactics and mitigate the risk posed by these dangerous interactions.”

The grand jury’s report, which was published in late June, is not binding or enforceable, but both agencies will have to provide a written response to the findings within 90 days.

In calling on local law enforcement agencies to revamp how they approach pursuits, the grand jury cited analyses by the Los Angeles Times showing that LAPD car chases have led to bystander injuries and deaths at twice the rate of pursuits in the rest of the state.

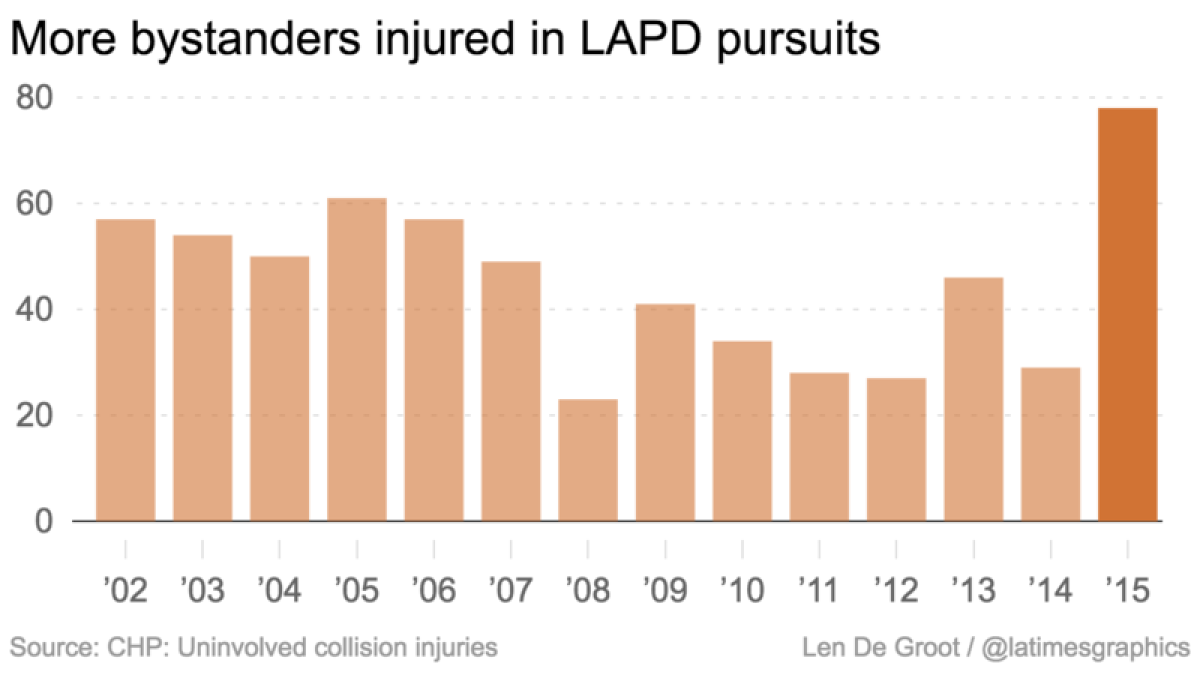

From 2006 to 2014, 334 bystanders were injured — or 1 in 10 LAPD pursuits, according to a Times review of pursuit data reported to the California Highway Patrol. In 2015, LAPD pursuits injured more bystanders than in any other year in at least a decade.

The grand jury report also highlighted the death of Jack Phoenix, a 15-year-old who was decapitated in November 2015 when he was struck by a car fleeing the LAPD.

In court, an LAPD officer testified that police noticed a stolen vehicle and followed it along the 10 Freeway and into the Palms neighborhood. The officer said she and her partner continued to follow the car at speeds above 60 mph without turning on their lights and sirens. They did not try to stop the driver as he sped along Venice Boulevard, where he eventually struck the teenager.

The LAPD has said it does not consider the incident a pursuit. The driver, Paul Brumfield, was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 27 years in prison in April. Phoenix’s family is suing the LAPD.

“It’s ridiculous in this day and age, with the kinds of technologies that are available, that they would have to chase a guy through traffic like that,” said Nick Phoenix, the victim’s father, adding that he was happy to hear about a push for policy reform.

Previously, experts have described the LAPD’s pursuit policy as one of the most permissive in the state.

Officers in many other major cities in California, including San Francisco, San Jose and Long Beach, are allowed to chase only drivers who present an immediate danger to the public or are suspected of violent felonies. Los Angeles police, however, are allowed to chase motorists suspected of felonies or misdemeanors.

The LAPD also chases suspected drunk and reckless drivers more frequently than other departments in the state, a practice that often is subject to criticism from policing experts, who say police are likely to cause an already erratic driver to become more dangerous by pursuing him or her.

Sheriff’s deputies are also allowed to pursue drunk drivers, but their policy is more restrictive, Gage said. Deputies are allowed to pursue a drunk driver only when they see a motorist driving in an extremely dangerous manner, Gage said. Deputies then must balance the danger posed by the driver against the possible risks of enacting a chase, he said.

“The deputy has to see the erratic, dangerous driving prior to them even trying to stop the vehicle. Then, we’re gonna activate our lights and sirens, not just to stop the suspect, but as a duty to warn the public,” he said. “Once we initiate, there is going to be a constant evaluation, if we’re going to cause the suspect to drive more erratically.”

The grand jury said the LAPD and Sheriff’s Department should provide officers with recurring training on driving in pursuits and each department’s trainers should investigate injuries at pursuit crash scenes.

Grand jurors described the Sheriff’s Department’s pursuit training facility as “substandard” compared with the LAPD’s and called for improved and longer training for deputies.

The LAPD has been working on revisions to its pursuit policy since 2015, officials previously told The Times, adding that the revisions were not in response to any public criticism of the department’s tactics. Nearly two years later, the policy revisions still are being negotiated with the union that represents rank-and-file officers, an LAPD spokesman said Tuesday.

Joanne Saliba, the grand jury forewoman, said she hopes the report leads to serious policy reform in both agencies, adding that some grand jurors were concerned about the way high-speed chases of low-priority suspects can endanger the lives of people who are simply going about their day.

“Many of them were concerned that these high-risk pursuits through urban areas at high speeds, especially for groups of people that haven’t committed a serious crime, seem to put the public at risk,” she said.

For more breaking crime and cops news in Southern California, follow us on Twitter: @JamesQueallyLAT

ALSO

Are Los Angeles police chases worth the risk to bystanders? Last year saw record injuries

California’s wildfire season has begun and you know the drill — or do you?

L.A. school board salaries more than double to $125,000 a year

UPDATES:

July 12, 2017, 12:45 p.m.: This article was updated with data on pursuit-related injuries from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

4:55 p.m.: This article was updated with comments from the grand jury foreperson.

1:45 p.m.: This article was updated with more details from the grand jury report, comments from a Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department captain, a statement provided by the LAPD and data from a previous Times’ analysis of LAPD pursuits.

10:45 a.m.: This article was updated with additional background on police pursuits in Los Angeles County.

This article was originally published at 8:25 a.m. July 11.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.