Must Reads: A swarm of 1,000 earthquakes hit Southern California — how nervous should we be?

- Share via

The seismic storm that unleashed more than 1,000 small earthquakes in San Bernardino and Riverside counties these last three weeks elicited what has become a typical reaction in quake country.

To some, the “swarmageddon” 40 miles east of downtown Los Angeles brought fear that a bigger threat was coming. To others, as long as they didn’t feel a shake, it was easy to just put it out of their minds.

California has small quakes all the time — a magnitude 3 every other day, on average. But not all of them act the same, and some bring more danger than others.

As officials install more seismic sensors as part of the state’s early warning system, experts are getting an increasingly better look at California’s smaller earthquakes.

There is general agreement that the recent swarm probably isn’t a precursor to a catastrophic quake. But other small quakes — especially ones near major fault lines like the San Andreas — are potential warnings.

“I would redefine normal as: You should still be prepared for a large earthquake,” U.S. Geological Survey research geophysicist Andrea Llenos said. “We do know a big earthquake is going to happen” — just not when and where.

The last time earthquake scientists were especially concerned in California about a large triggered earthquake was nearly three years ago.

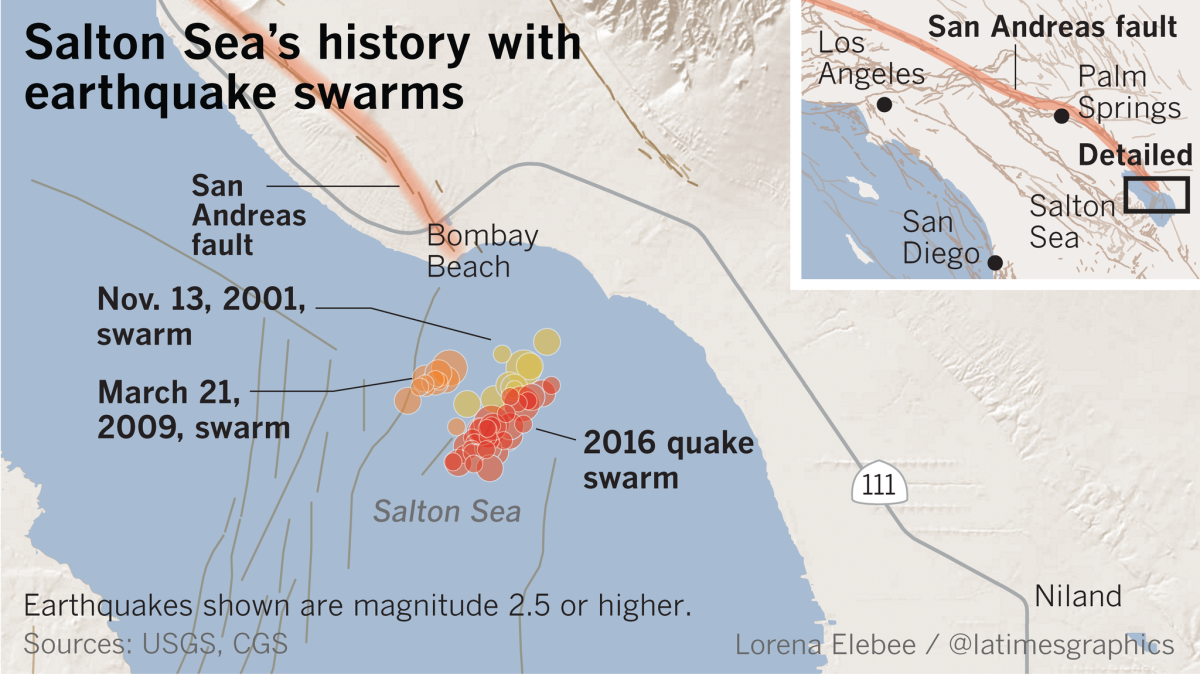

On Sept. 26, 2016, a rapid succession of small earthquakes — the strongest a trio measuring above magnitude 4.0 — began rupturing under the Salton Sea close to the San Andreas fault. Scientists worried those quakes could set off a domino effect, reawakening the southern San Andreas from its long slumber. That fault is capable of producing a magnitude 8.2 quake.

Their worst fears didn’t materialize.

But “any time you have an increase in the number of small earthquakes,” Llenos said, “you’re likely to increase the likelihood of a slightly larger earthquake happening.”

There have long been myths associated with small quakes.

“Half the people are saying, ‘Oh, they’re having a lot of earthquakes — it gets rid of the energy, it makes us safer.’ And half of them are going, ‘Oh, my God, we’re having earthquakes. We’re going to have the Big One,’ ” seismologist Lucy Jones said.

“The idea that little earthquakes make the Big One less likely doesn’t work. And the idea that it makes it certain to happen doesn’t work,” Jones said. “Any earthquake has a slight increase in the chance of having something” worse coming next, she added. “But mostly, it’s really small.”

(There’s only a 5% chance any particular earthquake will be followed up by something larger.)

The Fontana-area earthquake swarm that began May 25, with its largest event a magnitude 3.2, was much less of a concern — it’s quite a ways away from the San Andreas and San Jacinto faults, two of California’s scariest. That’s why, Llenos said, “it’s probably not going to affect the likelihood of larger earthquakes happening.”

Most swarms aren’t cause for concern and can be thought of simply as “a bunch of small earthquakes that are more of an irritant than otherwise,” Caltech seismologist Egill Hauksson said. There was the 2015 Fillmore swarm in Ventura County, for example, with more than 1,400 quakes, maxing out at magnitude 2.8.

According to Jones, there’s nothing particularly more ominous about swarms versus a single small temblor.

Places that have fluids moving around underground, where magma can heat up groundwater, are more likely to have swarms. They include the Salton Sea geothermal field in Imperial County, the Coso volcanic field of Inyo County, Mammoth Mountain in Mono County and the Geysers geothermal field in Lake, Mendocino and Sonoma counties.

There’s an ongoing earthquake swarm around the town of Cahuilla, about 20 miles east of Temecula in Riverside County, that started in 2016 and is moving westward and getting shallower, probably triggered by the movement of groundwater. But it’s not particularly close to any major faults.

Other swarms are more concerning.

RELATED: Get ready for a major quake. What to do before — and during — a big one »

In the Bay Area, the San Ramon Valley has had many swarms over the last several decades that haven’t resulted in large earthquakes, Llenos said. One swarm in 2015 generated 4,000 quakes over five months, according to the Berkeley Seismology Lab.

Still, that activity is occurring close to the Calaveras fault — capable of producing an earthquake as big as the magnitude 7 along the East Bay’s Hayward fault in 1868.

“Just because it’s something we haven’t had in the past doesn’t mean it’s not going to happen in the future,” Llenos said.

For decades, Jones said, scientists have detected a line of small earthquakes running southwest to northeast between Jurupa Valley and Fontana, on a geological feature called the Fontana seismicity trend, which isn’t officially a fault.

“Probably … it’s such a young fault, it hasn’t coalesced into an ongoing structure,” Jones said.

Though there’s only a slim chance any particular earthquake will trigger something far worse, experts say, it’s important to not completely relax.

When a swarm hit central Italy in 2009, according to seismologist Tom Jordan, one civil protection official sought to calm residents’ jitters by telling reporters: “The scientific community tells us there is no danger, because there is an ongoing discharge of energy. The situation looks favorable.”

A few hours after a magnitude 3.9 earthquake jolted the town of L’Aquila that April 5, a magnitude 6.3 struck, killing more than 300 people.

And a magnitude 7.3 earthquake off the east coast of Japan on March 9, 2011, led some people to be complacent when, two days later, the historic magnitude 9 earthquake struck. Some people ignored protocol and failed to immediately evacuate before the catastrophic tsunami hit.

So while some might focus on the chance that the Fontana swarm won’t result in a much larger earthquake, said Ross Stein, chief executive of Temblor.net and a former USGS research geophysicist, it wouldn’t be surprising if a magnitude 6 or 6.5 struck the area.

“You can dismiss the swarm altogether, but … you still have an issue that you should address,” Stein said.

John Vidale, professor of seismology at USC, said it can be hard to communicate the risks to the public.

“The increase in danger [from a swarm] just takes it from a ‘very low’ level to ‘low’ level of danger. And telling the public that there’s a 1-in-1,000 chance instead of a 1-in-10,000 chance of an earthquake today is very difficult,” Vidale said.

Those slim chances do happen, however.

At least three times in California’s modern history, large earthquakes have occurred in the wake of smaller temblors:

Central and Southern California, 1857, magnitude 7.8: The last mega-earthquake in Southern California struck Jan. 9, 1857, sending extreme shaking everywhere from Monterey County south to Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties. The main shock, at 8:24 a.m., was preceded in the Monterey County area by a magnitude 5.6 earthquake, and a magnitude 6.1 earthquake the hour before that.

Northern California, 1989, magnitude 6.9: The earth was shaking in the months before the Oct. 17, 1989, earthquake in the Santa Cruz Mountains interrupted the World Series between the Oakland A’s and San Francisco Giants — a magnitude 5.4 quake two months earlier and a magnitude 5.3 in June 1988. Jones said many scientists believed those quakes — not foreshocks, but something called “preshocks” — were related somehow to the Loma Prieta earthquake, which killed 63 people that October.

Southern California, 1992, Joshua Tree-Landers-Big Bear: Earthquakes following the magnitude 6.1 Joshua Tree temblor April 22, 1992 — strong enough to rock high-rise office buildings in downtown Los Angeles more than 100 miles away — kept on migrating to the north. It began “the most substantial earthquake sequence to occur in California in the last 40 years,” according to a study published in 1993 and co-written by Hauksson and Jones. The Joshua Tree quake is believed to have triggered on June 28 the magnitude 7.3 Landers earthquake in the Mojave Desert, strong enough to send shaking to Denver; a few hours later, a magnitude 6.3 hit Big Bear.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.