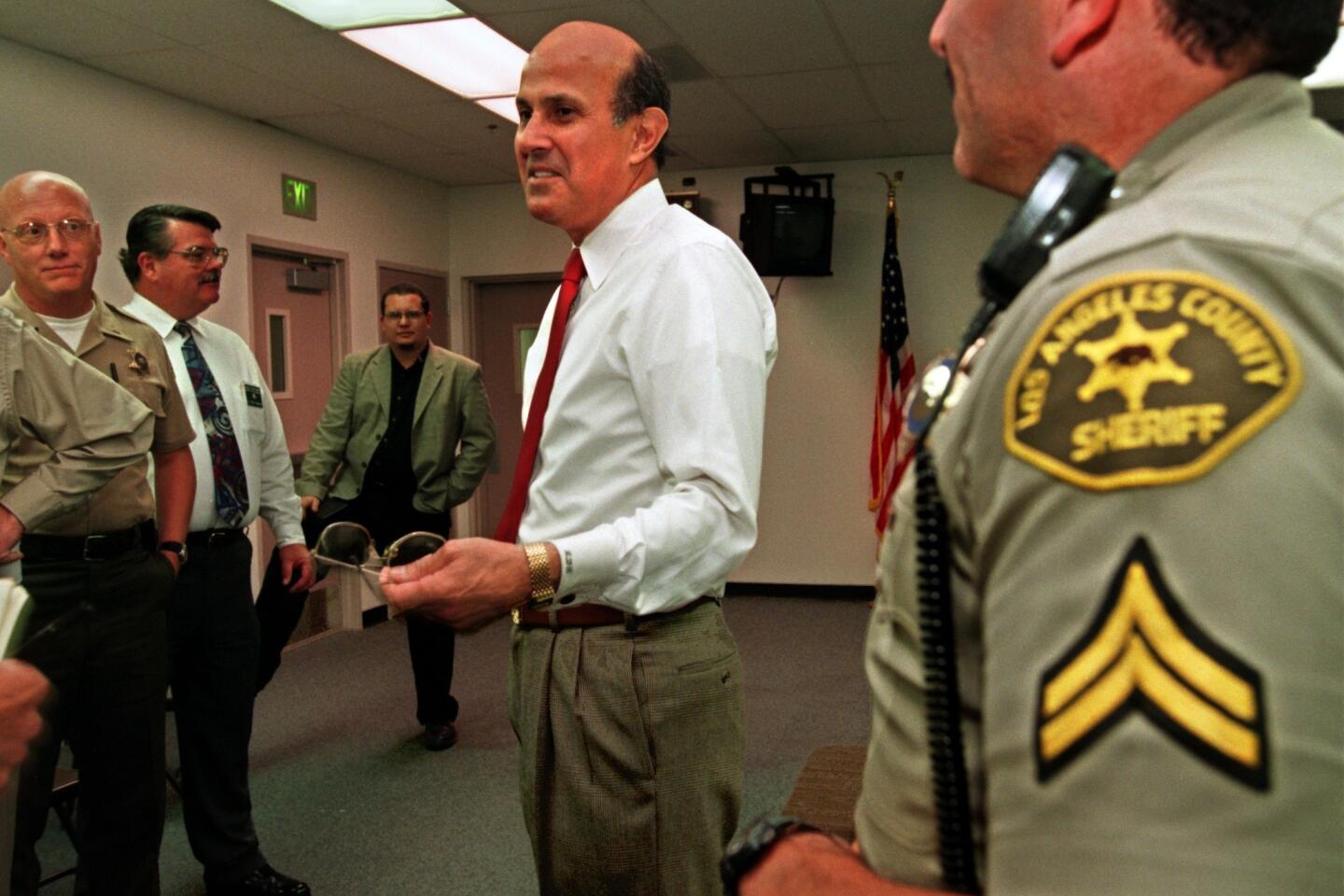

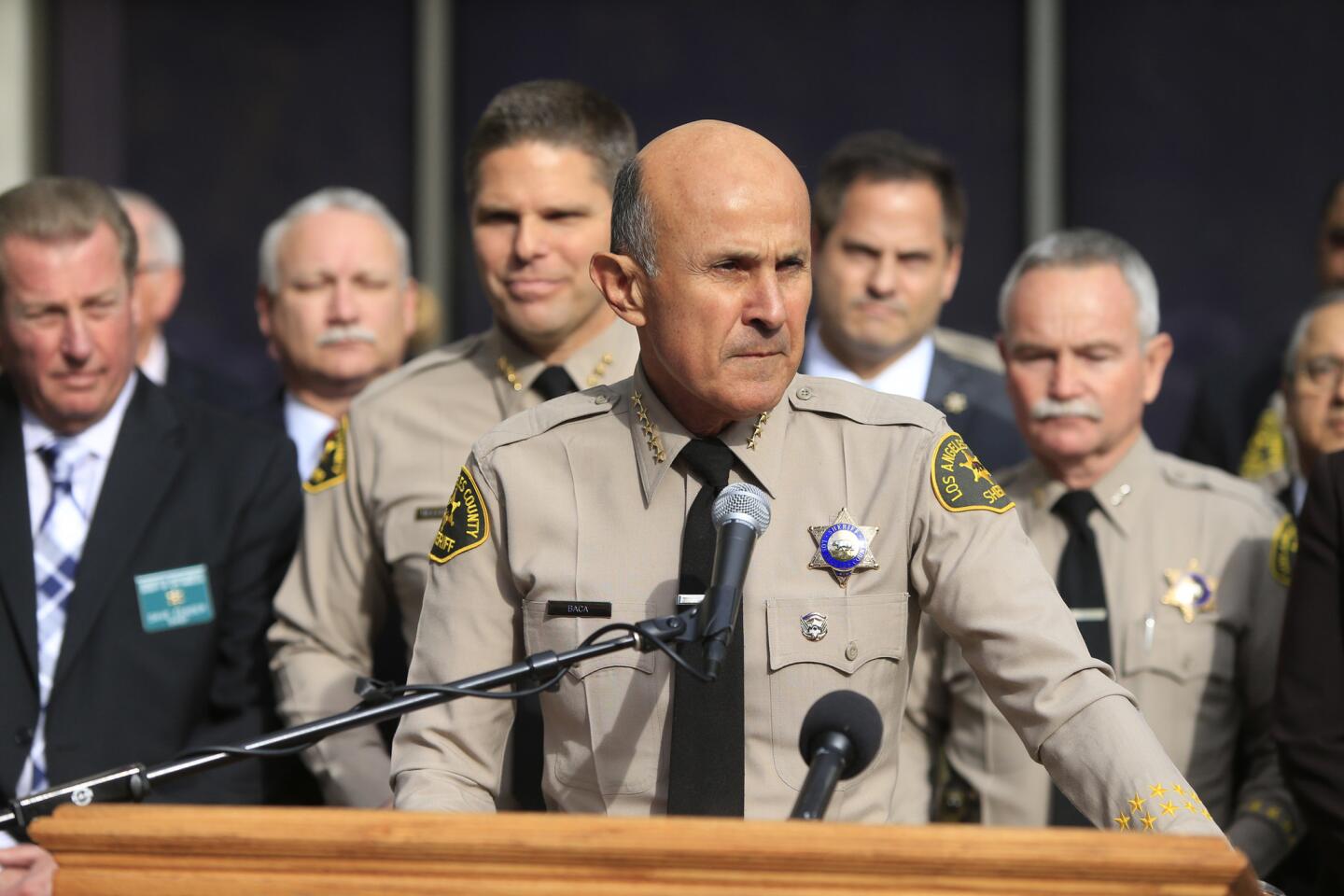

Former L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca found guilty on obstruction of justice and other charges

Former L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca speaks with reporters after he was found guilty of obstructing a federal investigation into abuses in county jails and lying to cover up the interference. (Video by Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

- Share via

Lee Baca, the once powerful and popular sheriff of Los Angeles County, was found guilty Wednesday of obstructing a federal investigation into abuses in county jails and lying to cover up the interference.

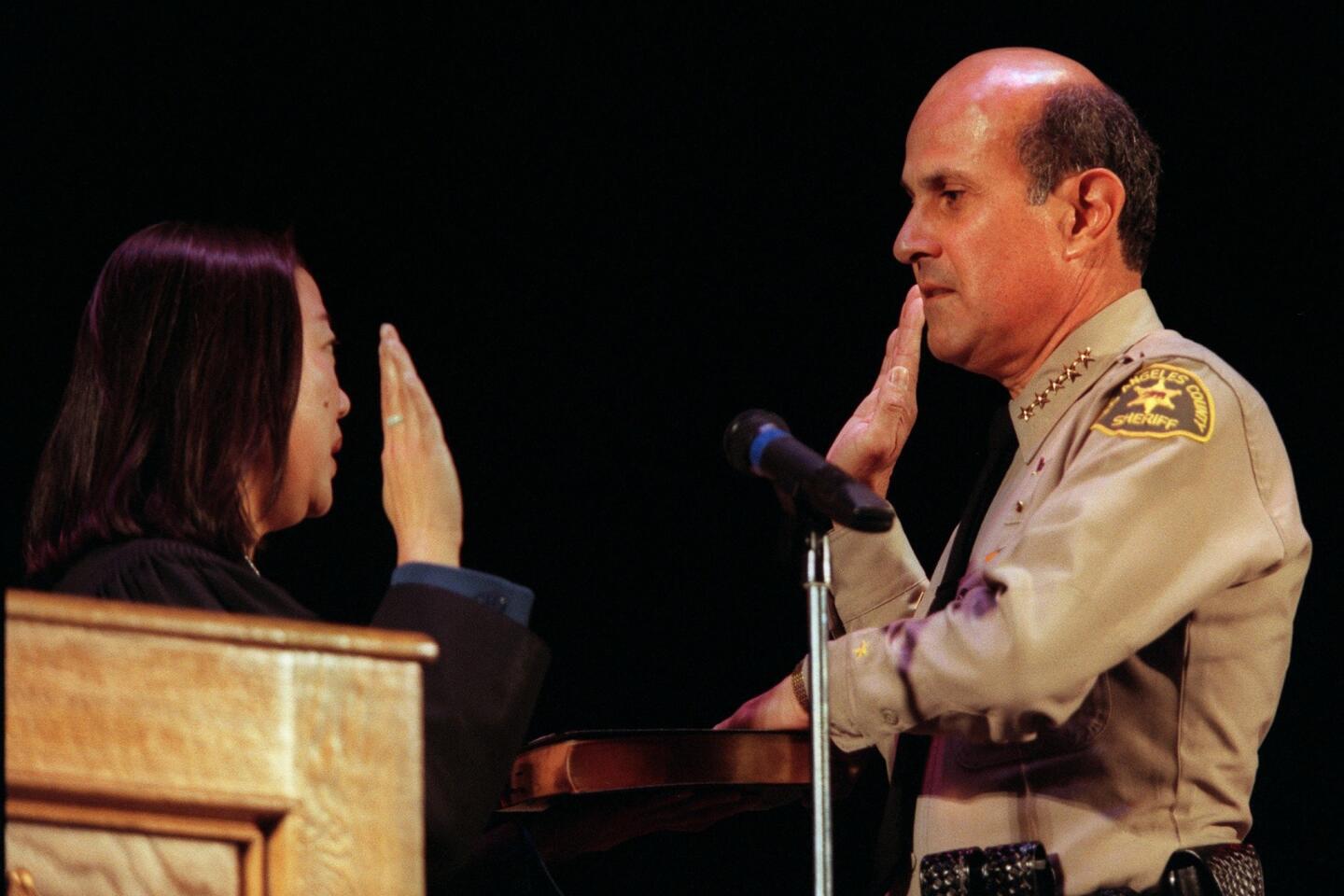

The verdict, which jurors reached on their second full day of deliberations, marked a devastating fall for a man who in his 15 years as sheriff built himself into a national law enforcement figure known for progressive ideas on criminal justice issues. Baca, who is 74 and suffers from the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, now faces the likelihood of time in federal prison.

Baca showed no emotion as the verdicts were read in a packed downtown courtroom.

“I disagree with this verdict,” Baca told reporters afterward. “My mentality is always optimistic. I look forward to winning on appeal.”

Speaking outside after the verdict was read, the jury foreman, a 51-year-old salesman from Los Angeles, knocked down Baca’s central claim that he was unaware of the malfeasance others in the department were carrying out.

“The leader runs the ship,” the foreman said. “He made the choice to be there. Step up to the plate and be responsible.”

The conviction is a significant victory for a team of public corruption prosecutors from the U.S. attorney’s office who opted to retry Baca following a mistrial late last year. In that trial, the jury deadlocked 11 to 1 in favor of acquitting the former sheriff.

Acting U.S. Atty. Sandra Brown said “this verdict sends a clear message that no one is above the law.... With a career in law enforcement, he knew right from wrong. And he made a decision that was to commit a crime … and when the time came, he lied — he lied to cover up his tracks.”

To get to Baca, prosecutors methodically worked their way up the ranks of a group of sheriff’s officials who were accused of conceiving and carrying out a scheme to impede the FBI jail inquiry. In all, 10 people — from low-level deputies to Baca and his former second in command — have been convicted or pleaded guilty. Several other deputies have been found guilty of civil rights violations for beating inmates and a visitor in the jails.

Prosecutors argued that Baca was part of a conspiracy, hatched in the summer of 2011, to obstruct attempts by the FBI to investigate allegations of corruption and abuse by deputies in his jails.

Although Baca delegated day-to-day handling of the obstruction plot to his trusted undersheriff, Paul Tanaka, he helped direct it and was kept apprised of developments from his place at the top of the command chain, prosecutors led by Assistant U.S. Atty. Brandon Fox told jurors. The scheme, prosecutors argued, included efforts to keep FBI agents away from an inmate who had been working for them as an informant, manipulating potential witnesses in the federal inquiry and intimidating an FBI agent.

In his closing words to the jury before they began deliberating, Fox excoriated Baca, comparing him to a cowardly chess king who remained safely back while dispatching pawns and other underlings to do his “dirty work.”

Baca’s defense attorney, Nathan Hochman, had tried to convince jurors that while Baca was upset over the FBI’s decision to secretly infiltrate his jails, he never attempted to get in the way of the federal investigation. It was Tanaka alone who directed the effort to foil the federal inquiry, Hochman contended, saying the undersheriff took advantage of the trust Baca put in him to pursue his own agenda. Baca, his lawyer argued, did not know what was going on.

Jurors convicted Baca of three felonies: obstruction of justice, conspiracy and making false statements to federal investigators.

As is typical for nonviolent felons, Baca was allowed to remain free until he is sentenced at a hearing in the coming weeks. The hearing date will be set next week.

Tanaka, who was convicted last year of obstruction of justice and conspiracy, received a five-year sentence from U.S. District Judge Percy Anderson, who also presided over Baca’s trials and those of the others caught up in the obstruction case.

The jury foreman, who declined to give his name, said eight of the 12 jurors voted to convict Baca in the first poll the panel took. Over about 15 hours of deliberation, the four jurors leaning towards acquittal were convinced of Baca’s guilt through discussion of the evidence, he said.

The testimony of former Assistant Sheriff Cecil Rhambo was particularly persuasive, the foreman said. Rhambo recounted for jurors how he had tried strenuously to warn Baca that he would cross into criminal territory if he pursued the obstruction plan.

The group of eight men and four women ultimately reached the unanimous conclusion that Baca was guilty of interfering with the FBI and later lying about it, but the foreman said he and others on the jury understood the anger Baca felt over the federal investigation.

“We felt at times he was trying to protect his empire, if you will — what he worked so hard to attain,” the foreman said. “He rightfully got defensive.”

The case focused on six weeks in August and September 2011 following the discovery by sheriff’s officials that FBI agents had bribed a deputy to smuggle a cellphone to their inmate informant, a convicted violent felon. The sting operation was part of a larger investigation into allegations of widespread corruption by deputies working in the jails, including claims that inmates were routinely beaten without justification.

Baca, whose public persona was of a gentle and thoughtful, if eccentric, leader, seethed over what he saw as an incursion into his territory, prosecutors said. His anger fueled a deliberate effort to subvert the FBI and the grand jury impaneled to hear the evidence gathered by the agents.

Others who participated in the conspiracy testified at the retrial that the sheriff called a meeting early on where he gave the assembled group directions, including to keep the inmate, Anthony Brown, safe and investigate how the phone was smuggled to the inmate.

While Hochman argued at trial that these were reasonable and necessary steps that were quickly perverted by Tanaka, the government said the orders were thin cover for Baca’s more malevolent intentions.

In the ensuing weeks, Brown’s name was erased from jail computer systems and he was re-booked in various facilities under fabricated aliases — a deception done with Baca’s knowledge that was meant to keep the FBI from finding their informant, former sheriff’s officials testified at trial.

Baca, prosecutors alleged, was also part of a decision to send deputies to the house of the lead FBI agent in the case in an attempt to intimidate her. And he was kept abreast of attempts by members of the group to pressure and cajole deputies and Brown to dissuade them from cooperating with the federal investigation, according to prosecution testimony at trial.

A cache of emails, along with phone records and testimony, led to convictions against Tanaka and the others in the group. But without nearly as much evidence pointing to his knowledge and involvement in the obstruction plan, building a case against Baca proved to be difficult.

Seeing the weakness in their case, prosecutors tried to avoid a trial and struck a deal with Baca last year that called for him to plead guilty to a single count of making false statements to federal investigators and spend no more than six months in prison.

The agreement fell apart when Anderson deemed it too lenient.

After nearly losing in the first trial, prosecutors made changes to their case.

They called, for example, former Lt. Greg Thompson. Thompson, who received a 37-month sentence for his role in the conspiracy, told jurors that he had been prepared to send Brown to state prison, but that Baca ordered him to keep the FBI informant in the county jails run by the Sheriff’s Department.

And Thompson added a previously unknown detail to a conversation he had with the sheriff. After FBI agents were allowed into the jail to speak with Brown despite orders that he be kept from visitors, Thompson went to the sheriff’s office to apologize.

Baca, he said, was calm and told Thompson the slip-up was part of a “chess game” — a statement prosecutors said pointed to Baca’s attempt to outmaneuver federal officials. Fox exploited the chess reference in opening and closing statements, referring to Baca as the king of the game.

And former Capt. William “Tom” Carey, who agreed to testify for the government as part of a plea deal and has yet to be sentenced, told jurors Baca was present for a meeting in September where it was decided that two sergeants should go to the home of the lead FBI agent, who had been under surveillance for days.

“He was OK with it,” Carey testified of Baca. “He didn’t tell us not to do it. His advice to us was just not to put handcuffs on her.”

In the retrial, Baca faced a charge of making several false statements to investigators during an interview he gave Fox and others in 2013, in which he denied knowing about the plan to obstruct the FBI. In the first trial, the judge set the lying charge aside for a later trial, but he added it back at Fox’s request for the second go-around.

Adding the false-statement charge back opened the door for Fox to play excerpts of the interview — something he could not do in the first trial.

In the face of the government’s adjustments, Baca’s attorney, Hochman, stuck largely to the script that almost won Baca his freedom in the first trial. He tried to poke holes in the government’s case by emphasizing its circumstantial nature and the lack of a clear smoking gun.

Hochman was hindered by several rulings Anderson made before the retrial. A psychiatrist, for example, was barred from testifying about Baca’s diagnosis with Alzheimer’s disease. Hochman had wanted the psychiatrist to share his belief that the illness could explain why Baca might have made inaccurate statements to prosecutors during the recorded interview.

Stymied by Anderson on the types of defenses he could mount, Hochman called only a single witness on Baca’s behalf. Baca did not testify in his own defense.

In comments to reporters after the verdict, Hochman criticized the government for the “win-at-all-cost approach” he said it took in its pursuit of Baca and alluded to the restrictions Anderson imposed.

“The jury is only as good as the evidence it gets to consider,” he said. “Here, the jury did not get to consider all of the evidence.”

Follow @joelrubin and @vicjkim on Twitter

ALSO

Charges filed against L.A. County probation supervisor in videotaped jail beating

ICE agents make arrests at courthouses, sparking backlash from prosecutors and attorneys

Judge throws out murder conviction, orders man released from custody after 32 years behind bars

UPDATES:

6:25 p.m.: This article was updated with additional comments from the acting U.S. attorney, the jury foreman and Baca’s attorney.

4:15 p.m.: This article was updated with additional information from the trial and comments from the jury foreman and from Baca.

This article was originally published at 2:10 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.