Years after brutal stabbing, East L.A. bar owner’s slaying solved by LAPD reserve police officer

The murder is believed to be gang related, and Smith is still working to identify others involved in the murder. (July 24, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

- Share via

The last customers had left, and Alfredo Trevino was closing up the bar on Dec. 17, 2001 when two men in ski masks walked in and began stabbing him.

When it was over, Trevino lay dead on the floor of La Cita, the bar he owned in Boyle Heights, his body pierced with 104 stab wounds. The assailants had also beaten Trevino, a 71-year-old Mexican immigrant, with the cash register but had not taken the money.

On Trevino’s back, carved with a knife, was a symbol resembling a “W.” On a bloodstained bar napkin was another message: a sketch in red ballpoint pen of a skull with two knives through it, framed by the words “Feliz Navidad.”

Detectives interviewed witnesses and sent a piece of latex glove worn by one of the assailants for DNA testing. But the slaying remained unsolved.

La Cita, which played ranchero music and drew a crowd dressed in cowboy outfits, was taken over by Trevino’s son, who spruced up the interior and changed its name to the Whitt, after its location on Whittier Boulevard.

**

Through a political career that included a two-term stint on the Los Angeles City Council, Greig Smith moonlighted as an unpaid police officer.

His compensation was the excitement of the chase.

He initially worked a patrol car in the San Fernando Valley, but then-Chief William Bratton did not view that as an appropriate assignment for a city councilman, Smith said.

For years, Smith worked as a screener for cold case homicides, deciding which cases were worthy of further review. Then, his boss offered him an unprecedented opportunity: If he went to detective school, he could join the elite Robbery-Homicide Division and become a cold case investigator. No reserve officer in the Los Angeles Police Department had ever worked as a detective, let alone in such a prestigious assignment.

In January 2012, the Trevino file landed on Smith’s desk.

The first step was to check for a DNA match. Sixteen years ago, DNA testing was both primitive and expensive, and detectives were allowed to submit only a single item per case, Smith said.

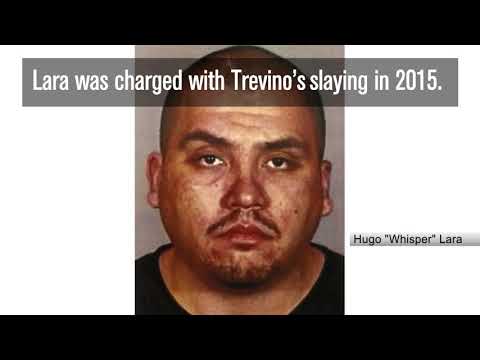

More than six months later, the results came back: a piece of bloody latex glove contained DNA matching that of a prison inmate named Hugo Lara, who was serving time for a robbery.

The chances of another Latino male possessing that same DNA: 1 in 4.2 quadrillion.

But who was Lara, and why would he want to kill Trevino? Who was the other stabber, and who was a third man who stood lookout? A coroner’s investigator determined that two different knives were used in the attack.

Smith tried to find the witnesses who had spoken to detectives years ago. One, a waitress who was in the bar during the stabbing, was dead. Another, the assistant bar manager, mentioned a fatal shooting that had occurred at La Cita almost exactly a year before Trevino was killed.

The bar was known to be a hangout for the White Fence gang, which controlled that area of Boyle Heights. In December 2000, three White Fence members got in a fight, and the bar’s unofficial bouncer shot them, killing one and wounding the other two.

Gang culture dictated that someone had to pay for the bloodshed, LAPD Officer Mario Morales said at Lara’s preliminary hearing in August 2016.

The “W” carved into Trevino’s back, matching the White Fence gang sign, spoke to retaliation. Even though Trevino was not involved in the shootings, it was his bar, and he had allowed the bouncer to be there.

“If they don’t retaliate, they’re seen as being weak,” said Morales, who was a gang officer in Boyle Heights for eight years.

Still, where did Lara fit in? Now 44, he worked as a car painter until he was arrested for the robbery in 2007.

In a jailhouse interview, he told Smith that he occasionally frequented La Cita. He belonged to a different gang, El Sereno Locke Street, that was friendly with White Fence, and he had painted the cars of White Fence members.

It is unknown why Lara would have done White Fence such a large favor. But gangs sometimes enlist nonmembers to commit murders so police will have a harder time solving the case, Morales said at the preliminary hearing.

In December 2015, Lara was charged with murder in Trevino’s slaying.

Earlier this month, as his trial approached, Lara struck a deal with prosecutors, pleading no contest to voluntary manslaughter, guilty to committing a gang-related crime and guilty to using a deadly weapon. At a sentencing hearing on July 31, he is expected to receive 22 years in prison.

Smith is still working to identify the second stabber and the lookout, as well as whoever may have ordered the hit.

“Just to say I put somebody in jail, really for life, and to be able to bring closure to a family that never thought it would happen — it’s a great feeling,” said Smith, 68, who usually works for the LAPD one day a week.

**

Alfredo Trevino’s was a classic immigrant success story.

After serving in the Korean War, he came to California, saving money he earned working at factory jobs until he could open a restaurant. Blanca’s in East L.A., which seated 100, was named after one of his five children.

He became increasingly prosperous, buying properties and supplying jukeboxes and pool tables to local bars. He eventually sold the restaurant and bought La Cita, stopping by every day to tend bar and manage the place.

After running the bar as the Whitt for 16 years after his father’s death, Trevino’s son sold it a few months ago.

Trevino’s daughter, Blanca Trevino, said Smith kept her updated on the investigation and made her feel like someone cared about what happened to her father.

“Wow, somebody’s actually working a case that’s in East Los Angeles,” Trevino said. “It’s not somebody famous, but they actually care about this.”

For more news on the Los Angeles Police Department, follow me on Twitter: @cindychangLA

ALSO

Sex, joy rides and car chases: Scandal in LAPD youth cadet program sparks alarm and calls for reform

USC received more than a year of questions about former medical school dean’s conduct before scandal broke

As cruising returns to Whittier Boulevard, officials look to decades-old restrictions

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.