Amid fear and resistance, immigration agents in L.A. have not ramped up arrests

- Share via

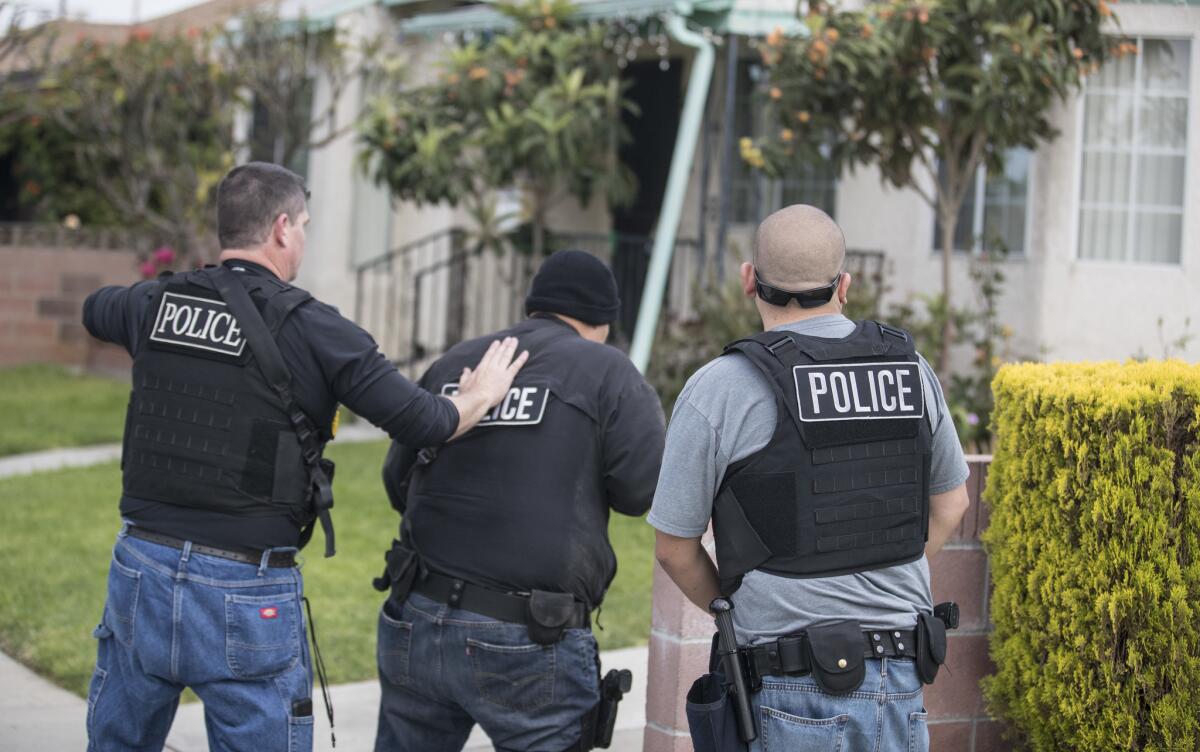

The immigration agents surrounded the small home on a quiet street in East Los Angeles. One trained his rifle on the back door. Another knocked loudly out front, shouting for the people inside to open up. Someone else barked the commands in Spanish.

Their target was a 47-year-old Mexican man who they suspected had crossed into the United States illegally and later done time for felony assault and battery.

The man’s wife came to the door after a few minutes with her own demands: Did the agents have a warrant?

Told that they didn’t, she refused to allow the agents in the house and said her husband would not speak with them.

Thwarted, at least for that day, the agents departed. As they walked to their SUVs, a neighbor stood in the street recording them on his phone.

As that recent stalemate suggests, President Trump’s calls for a dramatic increase in deportations has brought changes for ICE agents on the ground. A determined push by immigrant groups has led to more encounters with people aware of their rights.

And, after receiving relatively little attention for years, agents acknowledge the atmosphere and politics of the job has become more fraught as they work under increased scrutiny from politicians and activists.

“That’s just the climate that we’re in,” said Dave Marin, director of enforcement and removal operations for ICE in Los Angeles, “because this issue has brought up such heated concerns on both sides.”

But while arrests by ICE are up 35% nationwide since Trump took office, they remain relatively flat in Southern California. Arrests of immigrants without criminal pasts have remained low in the L.A. region as well, as agents do little, if anything, differently from what they were under the previous administration, Marin said.

The charged dynamics were evident when The Times accompanied a team of ICE agents as they carried out a series of early-morning arrests late last month.

‘I go to work! You guys have no heart.’

Hours before dawn, agents gathered in a shopping mall parking lot in Compton. A supervisor handed out paperwork with photos, immigration history and criminal rap sheets of the six men slated for arrest.

Two of the targeted men were arrested without incident in traffic stops shortly after leaving their homes to begin the drive to work — one as a tree trimmer, the other a chimney repairman. A third man hid inside his apartment when agents knocked, but was nabbed when he walked out to the street an hour later.

Next on the list was Sergio Rodriguez, who sneaked into the U.S. from Mexico in the early 1980s and managed to became a legal resident a few years later. For years, he worked and raised five children with his wife without attracting the attention of immigration officers; but a conviction in 2014 on a felony charge of making criminal threats and a few earlier burglary and theft convictions had made him eligible for deportation.

Rodriguez stepped out from his small, dilapidated house in El Monte, east of downtown Los Angeles, shortly after 7:30 a.m. to begin the short walk to his job at a nearby meat market.

Agents had been secretly watching him make the same walk at the same time for days and now were waiting for him. One agent slipped out of an unmarked SUV and followed behind, while a few others positioned themselves up ahead.

“Why are you doing this? What did I do?” Rodriguez shouted repeatedly in English and Spanish as the agents intercepted him, cuffed his hands and, after a quick pat down, put him in the back of a car. “I go to work! You guys have no heart. You have no heart!”

The agents’ presence did not go unnoticed. Seeing a live television report about the arrest, the mayor of El Monte called his police chief demanding answers. The chief, in turn, called Jorge Field, ICE’s assistant field office director for the L.A. region.

Field has grown accustomed to such calls. Elected officials in immigrant communities, where anger and fear has been stoked by frequent – and often inaccurate — reports spread on social media of ICE sweeps, have grown particularly sensitive to the agency’s presence on their streets.

Field took the call while driving to make the next arrest and calmly explained Rodriguez’s criminal past to the police chief. An aide to Rep. Grace Napolitano (D-Norwalk) emailed at the same time, demanding to know, “Are you in El Monte?”

Marin said he spends a considerable amount of his time meeting with local politicians, police and church officials in an effort to tamp down claims of ICE running amok in L.A.

It has, at times, been a hard message to sell in the current climate.

“As one of my bosses put it, ‘Fifty percent of the country is mad at us 100% of the time,’” he said. “Half the country wants us to do more, and the other half wants us to do less.”

After Trump dramatically broadened ICE agents’ authority, essentially giving them clearance to arrest anyone suspected of being in the country illegally, immigrant rights groups have pushed to educate immigrants on their rights — in particular to deny ICE agents permission to enter their homes. The effort has had a noticeable effect on arrest operations, Marin said, as agents increasingly have been stymied, as they were by the the Mexican man’s wife, who did not try to hide the fact that her husband was inside the house.

The Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, one of several immigrant advocacy groups that ramped up “Know Your Rights” campaigns in the wake of Trump’s election, estimates it has reached 25,000 people through various outreach programs over the past three months, the group’s spokesman said.

‘I knew this day would come’

Agents arrested four of the targeted men on the recent morning. Along with the man whose wife refused to cooperate, a sixth person was not found.

The men were brought to a federal building downtown. They were frisked and fingerprinted in a brightly lit hallway and then led into a room where agents seated at computer terminals booked the men into custody.

Afterward, they were put into large, spare holding cells with old televisions mounted to the ceilings. The telephone numbers for many countries’ embassies or consulates were posted on the wall above pay phones.

Juan Vega, 23, whose criminal history includes a 2014 gun possession conviction, seemed despondent and shell shocked as he sat on a bench with his head in his hands.

Brought to the country by his mother when he was 4, he said he had no idea what he would do if he was returned to Mexico. He cried thinking about his 6-year-old son.

If deported, he said, he wouldn’t return to the U.S. “I just want to get this over with,” he said.

Nearby sat Rodriguez, the meat market worker picked up in El Monte.

“In my head, I knew this day would come,” he said in Spanish. “This president that we have now has a lot of people scared. Anything you do, the police will arrest you and deport you.”

Like Vega, he worried about what would happen to his family. Who would take care of his wife, who has lung cancer? How will he see his adult children and grandchildren?

He said he wanted to send a message to others.

“Don’t make mistakes like I made,” he said. “It’s very sad.”

As of last week, Rodriguez, Vega and one of the other men arrested were being held in an detention facility as they waited for a hearing before an immigration judge.

The fourth man, whom a judge had already ordered deported, was removed from the country within days of his arrest.

Targeting serious criminals

ICE’s Los Angeles office covers a vast region that stretches from San Luis Obispo to San Clemente and from the coast to the Nevada border. There are nine teams of agents like the one that made the recent arrests, and at least one of them is active each day.

Other agents are assigned to arrest people as they are released from local jails. In counties where the sheriff allows it, including Los Angeles, Marin posts agents inside the jails to identify inmates in the country illegally.

When deciding whom to target for arrest, Marin said his agents have kept their focus on serious criminals, as they were instructed to do in the final years of the Obama administration. (Obama made criminals the priority for deportation late in 2014 following years of tough immigration policies that earned him the nickname the “Deporter in Chief” from critics.)

Each of the men whom agents pursued on the recent morning had been convicted of at least one felony. Along with Vega, Rodriguez and the man whose wife blocked agents, one man had been caught driving drunk three times and convicted of burglary, while another served time in jail for drug sales after being deported four times.

The reason for staying the course, Marin said, is rooted in the realities of California, where court decisions and state laws have left all of the state’s 58 county sheriffs unwilling and unable to fully cooperate with ICE’s requests to detain and hand over criminals thought to be in the country illegally. Instead, Marin said, his agents are often forced to track down people after they are released from custody.

Marin added that his agents are stretched thin as it is. “We’re already doing everything we can with what we have,” he said.

Arrests soar in other cities, but not L.A.

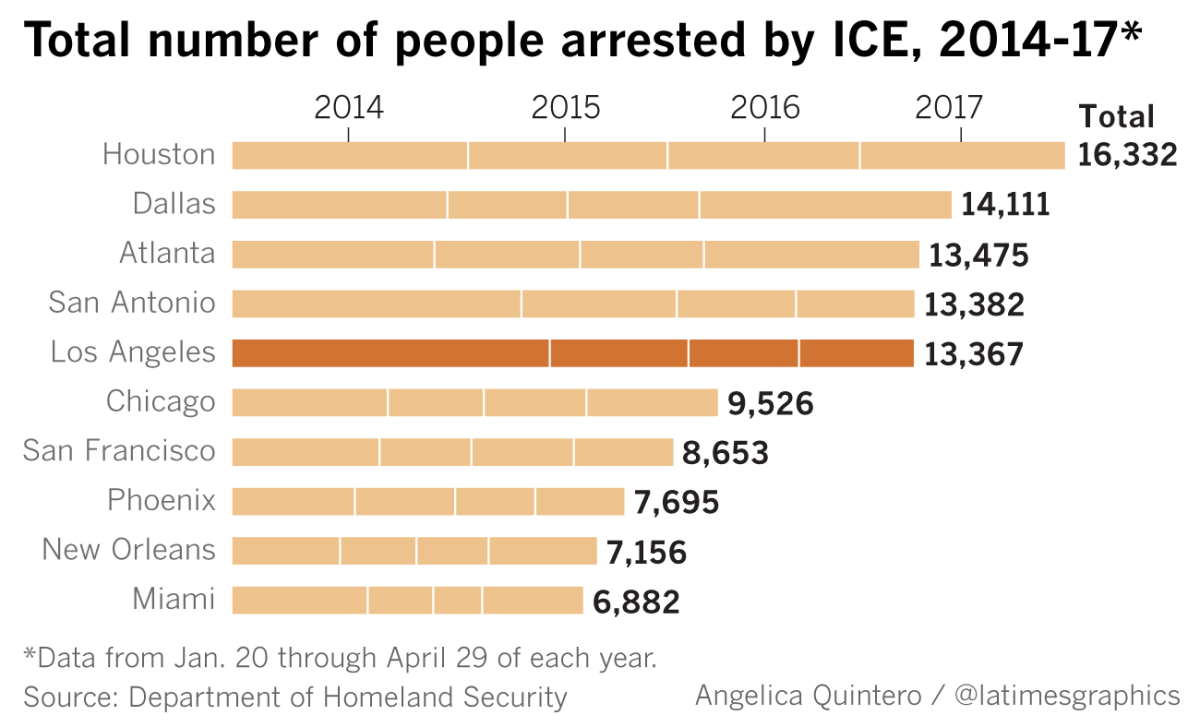

In the three months after Trump took office, agents in the L.A. field office made 2,273 arrests — marking little change from the 2,166 arrests during the same period last year and a decline from the 2,719 arrests in 2015, according to ICE figures. Ninety percent of the people arrested this year had criminal records, the highest percentage among all ICE offices in the U.S., the numbers show.

The L.A. figures differ starkly from those in Atlanta, Dallas and elsewhere, where the number of people without criminal records arrested by ICE jumped dramatically in the months since Trump took office. In Atlanta, for example, non-criminal arrests rose more than five fold over last year and accounted for a third of all ICE arrests.

While the number of non-criminals arrested in the L.A. region remains low, Jennie Pasquarella, director of immigrants’ rights for the ACLU of California, noted it had more than doubled over last year to 224 people.

“To the extent that Marin is continuing to follow the priorities set out by the Obama administration and is exercising restraint in immigration enforcement, that’s a good thing,” she said. “But I am concerned about the increase in arrests, especially of people who have never been convicted of any crime. It is too soon to tell what will happen.”

For more news on federal courts in Southern California, follow me on Twitter: @joelrubin

ALSO

Here's why some immigrant activists say not even criminals should be deported

Congressional bill seeks to prohibit immigration officers from identifying themselves as 'police'

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.