In Little Saigon, this newspaper has been giving a community a voice for 40 years

- Share via

The stories, spread in front of him in hot metal type, told of families stranded at sea, of sturdy ships rescuing rickety boats, of the hundreds drowned — all in the desperate struggle to get to America.

The articles brought news of people driven from Indochina by decades of war, and as he read them, his hands began to ink in accent marks over the words that needed them, so that their emotions burst forth, forming the narrative for the pages of his refugee newspaper.

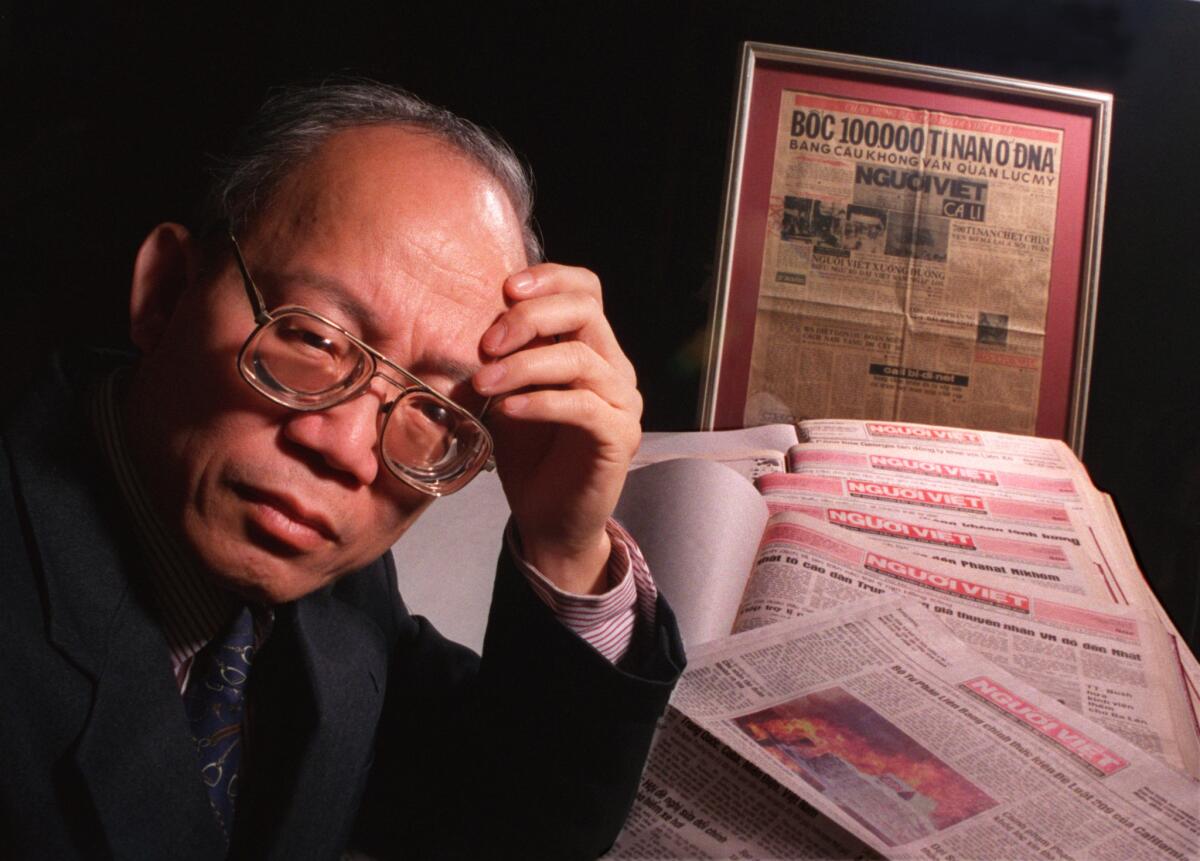

The year was 1978, when typewriters offered only English-language fonts. Yen Ngoc Do, sporting thick glasses, pored over each line, wanting to make sure the Vietnamese printed correctly. Nguoi Viet Daily News appeared once a week, those early issues splashed in red and black ink and selling for $6 for a three-month subscription.

In the tradition of community journalism, Do served as founding editor, publisher and circulation manager. Going door to door, he distributed 2,000 copies of what would become the largest Vietnamese-language publication in the United States.

Nguoi Viet, meaning “the Vietnamese people,” grew up with Little Saigon, the Orange County enclave that’s the biggest Vietnamese business and cultural district outside the motherland. In January a birthday party to celebrate its 40th anniversary drew nearly 800 people to its unpretentious building at the end of a Westminster cul-de-sac. An online readership joined the festivities, logging in from Australia, Canada, France and China, along with Facebook Live viewers from Vietnam.

In the tributes, and in the old photos lining the walls, beat the gentle, curious spirit of its founder, my father.

“Do you have much homework? Are you ready to help us?”

In sixth grade, I’d rush home every Friday after school, squeezing myself into a corner of the garage to begin bundling newspapers. I relished the sight of my ink-stained hands, refusing to wash them until dinner.

Bo, or “dad” in my parents’ native tongue, was born in 1941 in Saigon, the middle of five children. His family earned a living selling “couronne,” French-style funeral wreaths made from beaded flowers, thriving at a time Vietnam was under French colonial rule.

My father studied philosophy in college, but since high school he had never been a devoted student. Politics inspired him and he skipped class to organize rallies for social justice or to raise money for flood victims and the poor. One summer, he met my mother in the coastal city of Nha Trang; they were introduced by his cousin and in 1964, after they married, she continued her work as a schoolteacher.

Bo entered the newspaper business through an unconventional route. During the Vietnam War, he served as a combat correspondent for many publications, including Dai Dan Toc, an anti-establishment daily. His reporting helped him meet foreigners, among them an American professor who secured seats for him and his family on one of the last planes to the U.S., in April 1975, in the harrowing hours before Saigon fell. The Dos flew to Guam when I was 6, then on to Camp Pendleton, where the Marines welcomed the refugees.

Some three years later, Bo launched Nguoi Viet to try to connect the day-to-day happenings of the home country to the Vietnamese starting over in their adopted country. Seed money came from pinching pennies and wages from his job as a social worker and a wallpaper hanger in Texas. He wrote the first few issues in tiny lodgings in San Diego, quickly relocating to Orange County to be near the nascent community of newcomers. He had helpers but no employees, toiling on, spurred by a population of displaced people seeking its voice and emerging identity.

Bo always would ask if I was hungry before we started bundling the issues.

It didn’t matter that my friends bustled off to math or music lessons. There we were, I a mousy child among a cluster of rumpled men, racing deadline to drop off mailings before the post office in Santa Ana closed. Because we didn’t have enough money to buy sticker labels, I’d dip a toothpick into glue, dot the back of a strip of paper printed with an address and pat it down near the bulk rate stamp.

I’d do this a few hundred times before dinner, when our group would stream into the kitchen to scrub our grimy hands. My mom, cooking after a full shift at her electronics assembly plant, dished up and we, the roped-in volunteers, along with my younger brother and sisters, sat down to soup spooned over steamed rice.

Bo worried about how readers could maintain connections to distant friends and family, or how they could navigate the rules governing their new lives.

He decided to run more stories on the mechanics needed to balance living in both worlds — write-ups about the price of a kilo of rice so refugees would know how much money to send back to relatives in Vietnam. He spoke English — along with French, German and Chinese — and wrote stories explaining how the U.S. government system works. Back in Vietnam, the communist regime blacklisted the paper, which was smuggled in, while clandestine sources continued to feed Nguoi Viet news and information.

When the boat people began fleeing Vietnam in droves, the paper stayed true to documenting their sagas, sprinkled with excerpts of letters from Vietnam and personal reflections from those languishing in refugee camps in the Philippines and Malaysia.

“We may need to take in some very, very needy families,” Bo told our family.

One weekend, the door of our house, now in Garden Grove, opened to reveal unknown faces: Strangers had come to live with us, one of Bo’s buddies with a nursemaid and his five kids, our temporary roommates bedding down on our Goodwill furniture until they could strike out on their own.

No matter, more hands meant more help for behind-the-scenes newspaper work.

Nguoi Viet could always use another news source.

“The thing with your dad, he could never say no.”

That’s Jeffrey Brody, my father’s biographer, who captured his publishing years in an oral history released in 2003. Yen Do “was Little Saigon’s leading intellectual,” said the Cal State Fullerton communications professor and former Orange County Register reporter. For years, he met with my dad once a month and recorded their talks. “Since his death there has been a vacuum with no one taking his place. No one with the depth and scope of his knowledge.”

In the early 1980s, the paper transformed from a weekly to publishing twice a week, then three times, then five. A few miles away, fellow immigrants had opened the first Vietnamese-owned pharmacy, the first doctor’s practice, the first restaurant in conservative Westminster, where strawberry fields were still plentiful and the population solidly white.

People tapped Bo for favors around the clock. He spent weeks translating government forms and contracts. By the 1990s, California had become the first state to provide the written test for a driver’s license in Vietnamese, and a study guide to accompany it, but long before that, the newspaper had dissected the do’s and don’ts behind the wheel for immigrant first-time car owners.

Soon, strip malls surfaced along Bolsa Avenue, the main artery of Little Saigon, introducing herbal shops, dental clinics and bakeries. Myths swirled outside the community that all the Vietnamese lived off welfare. The refugees knew that they needed to “clarify the situation,” according to Bo’s recordings. “We needed to educate our activists in the community about long-term solutions, and we needed to build up a responsible image of the refugees.”

“We know it for its truth, and more often we know it as a bridge between the homeland and the new land.”

— Nguyen Ngoc Nhu Quynh, on Nguoi Viet Daily News

And so an activities room was added to the newspaper office at a new building the paper bought and moved to in 2002. Outside, the South Vietnamese flag flew next to the U.S. and California flags. Inside, Nguoi Viet could host events for the community and immediately report on them. And since Little Saigon lacks a social center, the space — where guests recently gathered for the 40th celebration — is a lively backdrop for poets, politicians, singers and photographers showcasing talks and exhibits.

The newspaper founded to chronicle a community helped create one.

“Really, that community room served as witness to all the meaningful reunions and challenges facing the Vietnamese,” Brody recalled. “A press conference followed every crisis. The most important activists and leaders among the Vietnamese appeared there. People could meet, talk and launch ideas to unify their goals. Yen Do always knew how to get people to the table.”

The community Bo eagerly covered has matured, both in size and sophistication, dominated by emigre politics. In 2008, dozens of people demonstrated for days when the paper ran a personal essay with a photo of a foot spa, splashed with the colors and stripes of the anti-communist South Vietnamese flag, calling it a desecration.

Today, huge swaths of the second generation speak and read English, leaving the publication — with a print circulation of about 10,000, a YouTube channel and 250,000 page views online daily — to struggle with how to reach them. Also, Nguoi Viet, housing a staff of 50, now competes with two other Vietnamese dailies, along with an assortment of magazines and radio and television stations.

(My dad gave away the majority of his company shares to co-workers as a reward decades ago, long before his death. My mother, who worked in classified advertising, retired in 2007. Disclosure, I now serve on the board of directors, helping with strategic planning on the business side.)

My father’s portrait hangs in the hallway leading to the design and layout department. At the anniversary party, blogger Nguyen Ngoc Nhu Quynh, a dissident released by Hanoi’s Communist government last October, strolled past it.

“We hear of Nguoi Viet newspaper in Vietnam,” said Nguyen, a leading critic of Vietnam’s one-party state, better known by her nickname “Me Nam” (Mother Mushroom). “We know it for its truth, and more often we know it as a bridge between the homeland and the new land. And we hear of Little Saigon, for Little Saigon is a symbol of the nation of Vietnam.”

It’s not surprising that when tourists from Vietnam and overseas communities around the world visit Little Saigon, they often want to take a tour of the newspaper.

One spring morning in 2006, before my dad turned 65 and a few months ahead of his passing from kidney disease, a journalist called from Radio France Internationale to ask about press freedom and its abuses in Asia. Pushing for such freedoms was Bo’s passion and the lobby of Nguoi Viet’s building reflects it. When newcomers walk in, they encounter a mural of the signing of the 1st Amendment, which he commissioned after translating it into Vietnamese to share with his readers.

A newspaper life, Bo told the radio interviewer, is never “solitary.” It’s a life “worth the risking for the learning and living.”

I embrace his essence, just as much as his words.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.