After 157 years in Chinatown, Los Angeles’ oldest hospital shuts its doors

- Share via

Xiaoyuan Yang was pregnant and her husband Weiming Lei needed a job when they moved more than 20 years ago from Guangzhou, China, to Los Angeles.

“We knew nothing, and we didn’t understand anything,” Lei said. “Someone told us to live in Chinatown.”

There, Yang found work at a Chinese restaurant, and their neighbors told them about a hospital just down the street where the staff spoke not only Mandarin and Cantonese, but the Toishan and Zhongshan dialects as well.

A Chinese doctor at the Pacific Alliance Medical Center gave them medical advice and taught them how insurance works. On June 1, 1995, after nearly a full day of labor, he helped them deliver their first child, a 7-pound girl named Sharon.

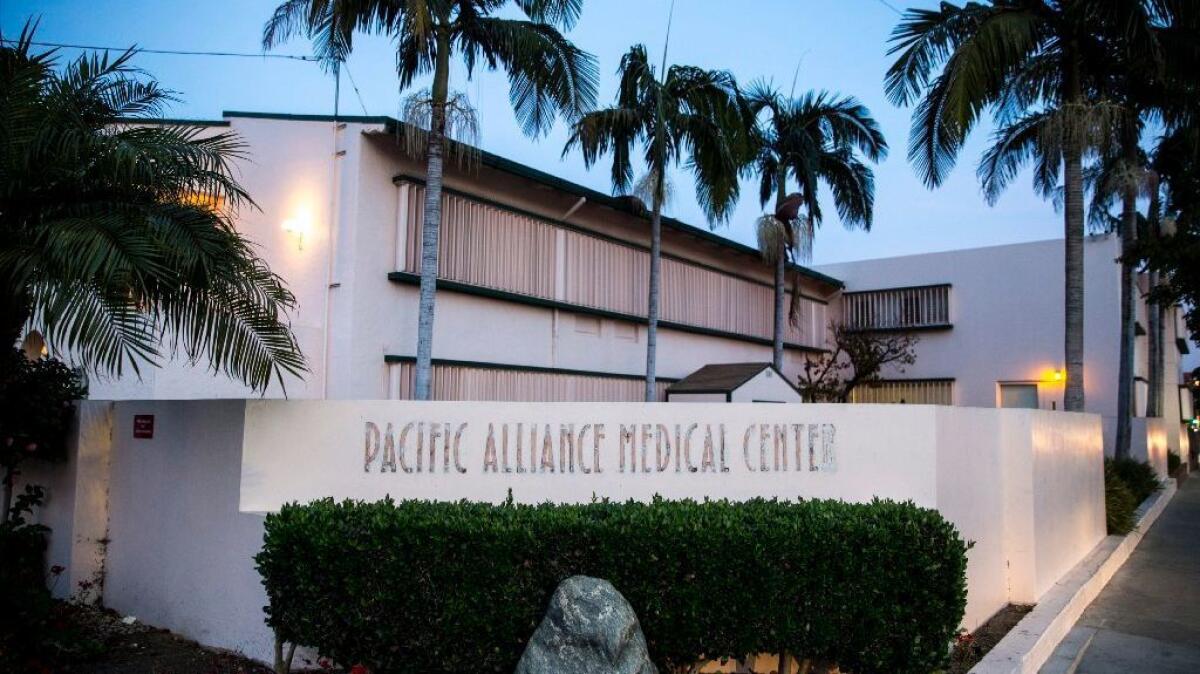

For decades, the Pacific Alliance Medical Center, better known as the French Hospital, has been Chinatown’s only hospital, serving a large population of seniors and recent immigrants and giving generations of “French babies,” as they came to be known, a reason to call Chinatown home.

On Dec. 11, the hospital’s lease expired, and all 638 of the facility’s employees were laid off.

After 157 years, like many Chinatown institutions in recent years, it closed quietly and without fanfare. The move sent shock waves through a Chinatown community struggling to preserve its historical identity as gentrification and investment creep north from downtown Los Angeles.

Residents say the hospital’s closure leaves seniors and families living in the area without an important option for healthcare. Community advocates worry about the economic impact of losing one of the neighborhood’s biggest employers.

Amy Mar, who has lived and worked in Chinatown for nearly 50 years, summed up another fear.

“Chinatown doesn’t feel like a place for Chinese people anymore.”

The French Hospital, the oldest hospital in Los Angeles, was established in 1860 during a smallpox scare to serve the 4,000-odd French people who lived in Los Angeles at the time. A few decades later, when Chinese people began to settle the area around the facility, it grew popular with Chinese immigrants.

The hospital’s cafeteria served congee, tea and stir-fried snow peas as well as oatmeal, coffee and steamed broccoli. It supported youth basketball teams at the Alpine Recreation Center across the street, offered health classes in multiple languages, and helped sponsor Moon Festivals and Chinese New Year celebrations, said Don Toy, a Chinatown community organizer who was born at the hospital.

A birth certificate from French Hospital became a source of pride for some Chinese Angelenos, an indication of how deep your roots in the community went, said Rick Eng, a French Hospital baby himself. Dr. Julius Sue, a Chinese doctor, became so well known in the community that the children he helped birth called themselves “Sue babies,” Eng said.

By 1989, at least 55% of the French Hospital’s patients were Asian. That year, a group of Chinatown investors and doctors took over the financially struggling facility and renamed it the Pacific Alliance Medical Center.

Hospital representatives say the percentage of Asian patients has dwindled to 11% in recent years. More than half of PAMC’s patients were Latino at the time it closed, the hospital said.

A representative of the Pacific Alliance Medical Center said the hospital chose not to renew its lease because state law requires the facility to complete nearly $100 million of earthquake renovations by 2030.

Investing that much money would be impractical, the hospital said, because someone else owns the land it sits on. PAMC, which has tried to buy the hospital land twice, owns only the parcel that the parking lot is built on and a different part of the property. Building a new hospital would have cost more than $400 million.

According to state records, the hospital posted operating losses of $53 million and $44 million in 2015 and 2016, respectively. This year, the hospital paid $42 million to settle a federal whistleblower lawsuit that alleged that it was forming illegal partnerships with doctors in exchange for patient referrals.

The nonprofit that founded the French Hospital, La Societe Francaise De Bienfaisance Mutuelle De Los Angel, still owns the property. The nonprofit has a two-year option to purchase the hospital’s parking lot, hospital representatives say. Gary Wilfert, vice president of the society, told The Times he could not comment on the nonprofit’s plans.

At a community meeting last week, many of Chinatown’s seniors said they relied on the hospital for medical care. They called upon city leaders to help build another hospital or keep the current one operating.

Waiwing Ng, who lives at a Chinatown senior living facility, said many seniors walked to the hospital to get care for ailments that are too trivial to call an ambulance or their adult children for, like severe indigestion or constipation. And dozens of seniors attended the hospital’s free classes about hypertension, nutrition, cancer, and how to use insurance.

“If we don’t have this hospital, it’s really hard for seniors to live here,” Ng said in Mandarin. “And if we can’t live here, we can’t afford to go anywhere else.”

Health advocates said that there are enough hospitals in the area to take on any displaced patients. Pacific Alliance Medical Center, a 138-bed acute care facility, wasn’t a high-volume hospital and didn’t have an emergency room, said Jennifer Bayer, spokeswoman for the Hospital Assn. of Southern California.

“There are a lot of hospitals within a 10-mile radius,” said Bayer, who described the impact on health services in the area as “very light.”

Toy and many other seniors say the hospital was one of the last reminders of a time when Chinatown was the vibrant epicenter of the Chinese community. Its closing has accelerated fears about gentrification and displacement.

“If we don’t do anything, in a few years, there won’t be a Chinatown,” said King Cheung, a community organizer.

A few years after giving birth to Sharon, Lei and Yang opened a gift shop in Chinatown where these days their their best sellers are portable radios and shoulder bags for seniors and luggage for tourists.

Sharon Lei, 22, grew up playing on the shop’s floors and helped run the store.

The long weekends at the shop taught her to respect her parents’ sacrifices and manage her time. She learned about the eye care industry from a Chinese optometrist across the street. Now she’s studying to be an eye doctor. Though her birth certificate says Los Angeles, she says Chinatown is her real hometown.

“It’s something I learned to be proud of as I grew older and shaped me a lot. It’s a place I still care about,” Sharon said.

These days she is studying optometry at the Southern California College of Optometry. After she graduates, she hopes to open her own practice in Chinatown.

That is, if she can afford the rent.

Twitter: @frankshyong

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.