From the Archives: Simpson Not Guilty: Drama Ends 474 Days After Arrest

- Share via

In light of the season finale of “American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson,” we’re looking back at the L.A. Times’ first-run coverage of the “Trial of the Century.” Written by Times staff writer Jim Newton, here’s The Times piece 474 days in the making: the verdict.

Bringing one of history’s most riveting courtroom dramas to a stunning climax, O.J. Simpson was acquitted of two counts of murder Tuesday, verdicts that set the football Hall of Famer free 474 days after he was arrested and charged with a brutal double homicide.

At 11:16 a.m., Simpson returned home to his Brentwood estate, embracing his longtime friend Al Cowlings in the same driveway where the two were arrested on June 17, 1994. As night fell, crowds of well-wishers and detractors gathered beyond police barricades while the Simpson entourage partied inside the famous home.

Within hours of the verdicts--broadcast live and bringing businesses across the country to a temporary standstill--family members of the victims retreated in grief, and the first of the anonymous jurors emerged to give The Times an interview in which he dismissed the prosecution’s physical evidence as “garbage in, garbage out.”

While jurors scattered to their homes, prosecutors, defense lawyers and family members of the victims and defendant gathered in an extraordinary series of news conferences.

In a statement read by his eldest son during one of the media sessions, Simpson expressed relief, gratitude and a commitment to finding whoever murdered his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Lyle Goldman.

“I am relieved that this part of the incredible nightmare that occurred on June 12, 1994, is over with,” Simpson said. “My first obligation is to my young children, who will be raised in the way that Nicole and I had always planned.”

Simpson vowed to pursue “as my primary goal in life” the killer or killers responsible for the murders, concluding: “I only hope someday that--despite every prejudicial thing that has been said about me publicly, both in and out of the courtroom--people will come to understand and believe that I would not, could not and did not kill anyone.”

After 266 days of sequestration at the Inter-Continental Hotel in Downtown Los Angeles, jurors deliberated a mere three hours before accepting Simpson’s contention that the charges against him were unproven.

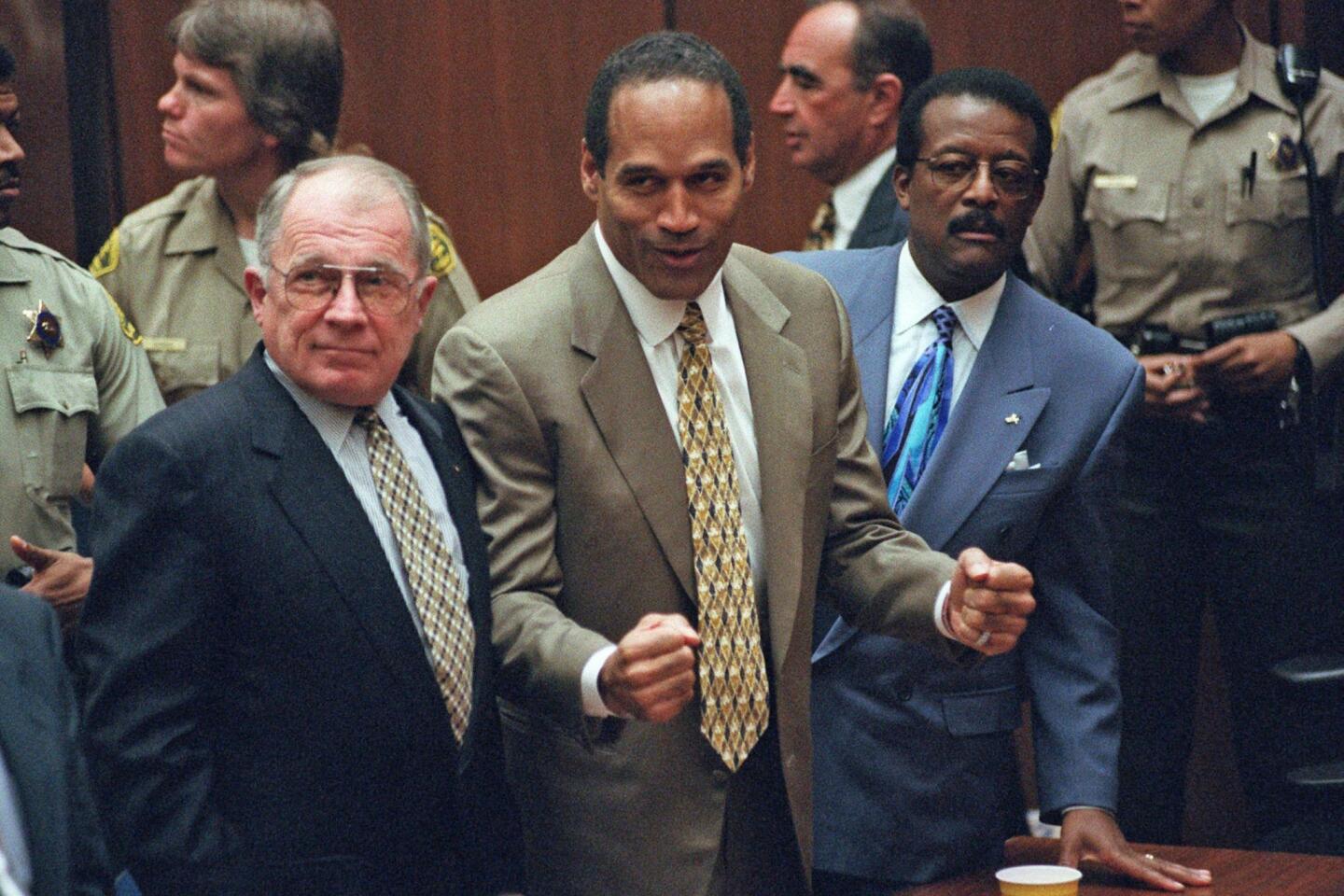

Their verdicts, which were delivered in a courtroom so tense that some spectators trembled visibly in anticipation, united jurors and Simpson in a strangely triumphant moment.

Simpson smiled thinly and mouthed the words “thank you” as the not guilty verdicts were read. Two jurors smiled back. Another, Lionel (Lon) Cryer, raised his left fist in a salute toward Simpson as the panel left the courtroom.

But the same finale was greeted with shock by the family of Nicole Simpson, and it wrenchingly broke the spirits of Goldman’s relatives.

Nicole Simpson and Goldman were knifed to death outside her Brentwood condominium on June 12, 1994, a foggy summer evening in an otherwise quiet neighborhood. O.J. Simpson pleaded not guilty to the crimes, but he was the only suspect, and members of both victims’ families came to believe that he was responsible for the murders.

In court, Fred Goldman, the victim’s father, stared in pain at the ceiling, his wife in one arm and his daughter in the other, both sobbing openly as the verdicts were read. In the quiet courtroom, Kim Goldman’s gulping sobs were the only sound that accompanied the reading.

“Oh my God,” Patti Goldman said, turning to her shaken husband.

“Murderer,” he said under his breath, repeating that later as he left the courtroom.

Kim Goldman, Ronald’s sister, fought to keep herself from speaking out while court was in session--Superior Court Judge Lance A. Ito had warned that any outbursts would be grounds for ejection. But after the verdicts were delivered, she could not contain herself. She quietly burst out a short string of expletives, then turned to the people sitting near her on the courtroom bench and apologized.

“I’m sorry,” she said, repeating that twice more as her long red hair cascaded over her tear-stained cheeks.

Later, Fred Goldman said the night of the murders “was the worst nightmare of my life.”

“This,” he added, “is the second.”

Prosecutors Solemn, Defense Celebrates

For the police who investigated the case and the prosecution team that brought it to trial and spent six months presenting what Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Gil Garcetti labeled a “mountain of evidence,” the quick verdicts were a devastating repudiation.

Deputy Dist. Atty. Christopher A. Darden turned toward the panel as it was being polled and glared at its members, his mouth half open in disbelief and dismay. None of the jurors would meet his gaze.

Next to him, Deputy Dist. Atty. Marcia Clark refused even to turn toward the jurors. She looked over her right shoulder and pursed her lips, expressionless but for the exhaustion in her eyes.

The two lead police investigators, Tom Lange and Philip L. Vannatter, sat a few feet away. They showed no emotion and declined to comment at length afterward. Asked whether he could believe the verdicts, Vannatter responded only: “No, not at all.”

Afterward, at a news conference featuring the district attorney team and the Goldman family, downcast prosecutors publicly thanked each other for their efforts but were obviously shaken by the swift dismissal of a case in which they summoned 72 witnesses during 99 days of testimony.

Clark, her voice thick and her eyelids heavy, expressed her sympathy and love for the victims’ families and thanked the members of her team for doing a “beautiful job.”

Darden stepped to the lectern next. The young prosecutor, who distinguished himself in the trial’s closing arguments, said he was not bitter about the verdicts, but when he began to thank his colleagues, he faltered: “I’m honored to have. . . .” he said. Then he paused, his voice tightening up.

With a small wave of resignation, he stepped away from the microphone and crumpled in the arms of the Goldman family.

Although Darden said he accepted the jury’s verdicts, his boss, Garcetti, conceded that he was angry.

“We are, all of us, profoundly disappointed,” he said.

“This case was fought as a battle for victims of domestic violence,” Garcetti said. “We hope this verdict does not discourage the victims, who are out there throughout our communities, throughout this country, from seeking help.”

For the defense team, the trial’s end represented an enormous legal triumph: Johnnie L. Cochran Jr., the defense’s lead trial lawyer, hugged colleagues and denounced pundits who viewed the verdicts as an indication of the predominantly black jury’s distaste for the LAPD rather than a reflection of its evaluation of the evidence.

“I just want to say how grateful we all are for this verdict,” Cochran said at the defense’s news conference. “We think the verdict bespeaks justice. We were always optimistic. That optimism proved right.”

He and the defense team were joined at the news conference by Simpson’s family--his mother, sisters and grown children--who effusively expressed their gratitude and relief. His mother, Eunice, said her belief in her son had never wavered, and her grandson, Jason, read his father’s statement.

Cochran said his client did not attend the news conference for security reasons--Nation of Islam guards were present at the courthouse and have provided security for the Simpson family and defense team in recent days.

But one of Simpson’s sisters, Shirley Baker, said family members were ecstatic: “I just feel like standing on top of this table and dancing a jig.”

A Case of Twists and Turns

The Simpson case tragically and violently began with a double murder in the normally placid Westside community of Brentwood. No credible eyewitnesses ever surfaced to the murders, but the culprit or culprits left behind a number of clues.

Bloody shoe prints from Size 12 shoes led away from the bodies, and drops of blood were found to the left of those shoe prints. A bloody glove and a knit cap were found next to the corpses.

Four detectives went to Simpson’s house before dawn that morning--they said they were there to notify Simpson of the killings and to help him care for his children, who were inside their mother’s home when she was killed. Once there, they jumped the fence and one of them, now retired Detective Mark Fuhrman, told his colleagues that he had found the mate to the bloody glove at the crime scene.

It was at that moment, Vannatter testified, that Simpson became a serious suspect.

Over the next few days, more pieces of evidence would fall into place that seemingly implicated Simpson: When he was interviewed by police on the day after the killings, for instance, police noticed several cuts on his left hand, one of which they believed was large enough to have left the blood drops at the scene.

Bloodstains also were found in Simpson’s car, and analysis of the drops leading away from the bodies revealed that they matched his blood type. A pair of his shoes revealed that he wore Size 12.

Still more evidence would surface later: A limousine driver interviewed by police said he saw a shadowy figure darting inside Simpson’s house just before 11 p.m. and Simpson then quickly answering the intercom. Simpson said he had overslept, but investigators believed that was a lie, that he actually had just returned from committing the crimes and was trying to hide his tracks.

Armed with sophisticated DNA tests, a history of domestic violence between Simpson and his ex-wife, and powerful circumstantial evidence suggesting that Simpson had the opportunity to commit the crimes, prosecutors boasted early on that convictions seemed likely, even inevitable.

Simpson and his high-priced but often divided legal team argued strenuously from the outset that he was innocent, and his lawyers launched an extraordinary assault on the police investigation.

Cochran accused police of a “rush to judgment” and attacked every aspect of the inquiry. According to Cochran and the rest of the legal contingent assembled by Robert L. Shapiro, coroners were not summoned promptly, criminalists were ill-trained and poorly supervised, and evidence in the case was hopelessly contaminated and corrupted.

A highly touted pair of DNA legal experts, Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld, were brought in from New York to take on the prosecution’s physical evidence, a task they tackled with vigor. With aggressive cross-examinations of prosecution witnesses, they challenged the evidence collection techniques, and they called Dr. Henry Lee, one of the nation’s foremost criminalists, who testified that “something’s wrong” with the physical evidence.

Although prosecutors responded to each point, jurors dismissed early in the case said they had doubts about the integrity of some evidence after hearing the defense challenge.

Then, just as the trial was winding down, the defense team dropped a bombshell whose impact will reverberate through Los Angeles long after the spotlight has moved from Simpson. One of the detectives in the case, Fuhrman, had given a series of interviews to an aspiring screenwriter; in them, he boasted of beating suspects, singling out minorities for brutal treatment and manufacturing evidence.

Gamely fighting back, prosecutors responded that Fuhrman’s evident racism and lying discredited him but should not taint the case as a whole.

Although Shapiro had once promised that race would not be an issue in the Simpson case, Cochran made no such pledge. In his closing argument, Cochran called Fuhrman a “lying, perjuring, genocidal racist,” compared him to Adolf Hitler and blasted the investigation as nothing short of a sham.

Joined by Scheck, he encouraged jurors to “do the right thing” and called on them to reject the Police Department and its Simpson investigation with not guilty verdicts.

That message carried the day.

One juror, returning home Tuesday, declined to comment in detail about the case, but her brief statement echoed Cochran’s argument.

“I think we did the right thing,” she said. “Matter of fact, I know we did.”

From the beginning of their deliberations, Cryer said, 10 panelists believed Simpson was not guilty; the other two, he said, came around after testimony of the limousine driver was read back to them. Cryer also dismissed the government’s central theory of the case: that Simpson had killed his ex-wife as the final act of a violent, controlling relationship.

“The prosecution tried to build a picture of him raging that day on June 12 to a point where he was wanting to be controlling of Nicole,” Cryer said. “And apparently he didn’t have that control anymore, and that’s why he went over there and killed her.

“To be honest with you,” Cryer said, “I never bought into it. I didn’t see it.”

Reaction Quick and Emotional

Throughout Southern Californian and the nation, reaction to the verdicts was heartfelt, and opinions often broke along racial lines--as they often have throughout the case.

Outside the courthouse, where crowds grew larger and more unruly in the trial’s closing days, demonstrators got word over radios and television sets. Dozens immediately burst into joyful shouts. Some pumped fists in the air. Some cried.

Bus riders traveling along Alvarado Avenue on the No. 18 line broke into cheers when the driver announced the verdicts over the loudspeaker system.

But in the Orange County neighborhood where Simpson’s children are being cared for by their grandparents, someone posted a sign reading: “O.J., you’re not welcome here.”

Tuesday night, the intense emotions that swept through the region all day coalesced at Simpson’s Brentwood estate, where supporters and detractors gathered outside the gates. Preachers shouted messages of love and forgiveness, and a saxophonist played “Amazing Grace” to a backdrop of helicopter noise.

The crowd’s chants of “O.J.! O.J.! O.J!” drew his sister, Shirley Baker, to the estate gate, where she briefly addressed news crews. “We just want to thank all you guys,” she said. “O.J. is home, and at a later time, he’s going to speak with you.”

But not all were there in support.

“What about Ron Goldman?” asked Shane Novak, who criticized Simpson and his lawyers for holding a party to celebrate the verdicts. “There’s no one playing a saxophone at Ron Goldman’s party now.”

In political circles, from Washington to Sacramento, there also was no shortage of comment on the case that has preoccupied the country for nearly 16 months.

President Clinton, who watched the verdicts from the Oval Office, wrote out a short statement in longhand.

“The jury heard the evidence and rendered its verdict,” he wrote. “Our system of justice requires respect for their decision. At this moment, our thoughts and prayers should be with the families of the victims of this terrible crime.”

Gov. Pete Wilson echoed Clinton’s sympathy for the families, but also argued that the long, contentious trial demonstrated the need for legal reforms. Wilson, who is a lawyer, said television cameras should be removed from criminal trial courtrooms, and recommended that attorneys be prohibited from asking juries for a “political message” such as the one sought by Cochran in denouncing the LAPD.

“I would urge the removal of cameras from our courtrooms,” Wilson said. “To contribute to turning a serious legal proceeding into a circus-like atmosphere is not in the interest of justice or public confidence in the justice system.”

Wilson also was fiercely critical of Cochran. “I find it particularly distressing, in fact it is more than that, when lawyers do not argue the issue at hand,” the governor said, “and instead ask jurors to use a verdict as a means of sending a political message to law enforcement.”

In Los Angeles, Mayor Richard Riordan, who broke off a trip to Asia to be at his post when the verdicts were announced, praised jurors for their “extreme sacrifices to meet the challenges of this trial.” The mayor urged residents to accept the panel’s decision.

“Whether we agree or disagree,” Riordan said, “we must accept the decision.”

Police Chief Willie L. Williams, whose department has been subjected to yearlong criticism and whose officers went on tactical alert Tuesday, said he hoped the jurors’ decision was not based on “the defense team’s decision to put my department on trial.”

“The vast majority of the men and women of the Los Angeles Police Department day in and day out put their lives on the line serving the people of our community,” Williams said. The chief urged residents to “move on . . . make sure all the races in this city work together.”

Nevertheless, many legal experts said the verdicts demonstrated how badly the LAPD’s credibility has eroded, particularly in the minds of many black residents.

“This just shows that you can’t get black jurors to trust LAPD,” said Harland W. Braun, an experienced defense attorney who represented Officer Theodore J. Briseno in the Rodney G. King civil rights case. “If you can convince jurors to eliminate any evidence that LAPD might have tainted, this is what happens.”

Steven D. Clymer, who prosecuted that case and won convictions against two of the officers, said the verdicts also demonstrated the power that charges of racism can bring to a criminal trial.

“I think it’s a tragic irony that O.J. Simpson, a person who probably never suffered the kind of racism that Mark Fuhrman dished out, is a beneficiary of the claims of racism,” said Clymer, now a professor at Cornell Law School. “I doubt that O.J. Simpson in his adult life experienced those things. I feel it’s a terrible result. I feel so bad for those families.”

But John Burris, an Oakland civil rights lawyer, said he considered the verdicts well-supported by the defense case and justified by the questions raised about the LAPD’s performance.

“The verdict is a perfectly sensible verdict in light of the evidence presented,” he said. “It reaffirms my faith in the good sense of African Americans that police misconduct won’t be tolerated.”

Although Tuesday’s verdicts mean that Simpson can never be tried again for the murders, they do not end the legal action spawned by the brutal murders nor Simpson’s legal troubles.

The district attorney’s office has indicated that it will consider perjury charges against Fuhrman, though most legal analysts say a conviction would be difficult to win. The Justice Department and the LAPD, meanwhile, are investigating possible criminal charges growing out of Fuhrman’s comments in the taped interviews.

And Simpson faces an immediate future still dotted by legal challenges. Three separate wrongful-death lawsuits have been filed against him, one by each of Goldman’s parents and the third by Nicole Simpson’s estate.

Those cases do not require a finding of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, only that jurors conclude that a preponderance of the evidence favors one side or the other. And they are unaffected by Tuesday’s acquittals.

Robert Tourtelot, the attorney who once represented Fuhrman and continues to represent Fred Goldman and his family in their lawsuit against Simpson, pledged Tuesday to pursue that lawsuit aggressively in the coming months.

“Today, the judicial system took a very big hit,” he said. “A lot of people will be looking to us for justice.”

Having successfully dispatched the criminal charges, Cochran and his staff will represent Simpson in those cases as well.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.