Gavin Newsom was a rising star — now he’s lieutenant governor

The ambitious former mayor of San Francisco chafes at the job’s limitations and lack of visibility. But he tries to keep his name at the forefront.

- Share via

For more than two years, Gavin Newsom has suffered the indignities of being the state's second-in-command.

His ideas about economic development and education are routinely ignored. He chairs a commission that's met only once. On the rare occasions he subs for the chief executive, protocol dictates he not make headlines. (In April, when Gov. Jerry Brown was in China, Newsom boldly declared a state vegetable. And fruit. And grain.)

On a Monday this spring, he was escorted off the Senate floor.

A security officer had told the lieutenant governor that he couldn't sit in the same room as lawmakers when they debated policy because he was a member of the executive branch.

Outside, Newsom slumped on a wooden bench, his face that of a star pupil who'd been sent to the principal's office.

"I've actually presided over the damn thing," he said, noting his ceremonial role as president of the Senate, one of his few official duties. "It's kind of ironic."

Just then, a woman stopped and asked Newsom — former San Francisco mayor, hero to the gay rights movement, gubernatorial contender — if he would pose for a picture with her son. Newsom put his arm around the boy and flashed a Hollywood smile.

"What's a lieutenant governor?" the boy asked.

Newsom kept his gaze on the camera.

"I ask myself that every day."

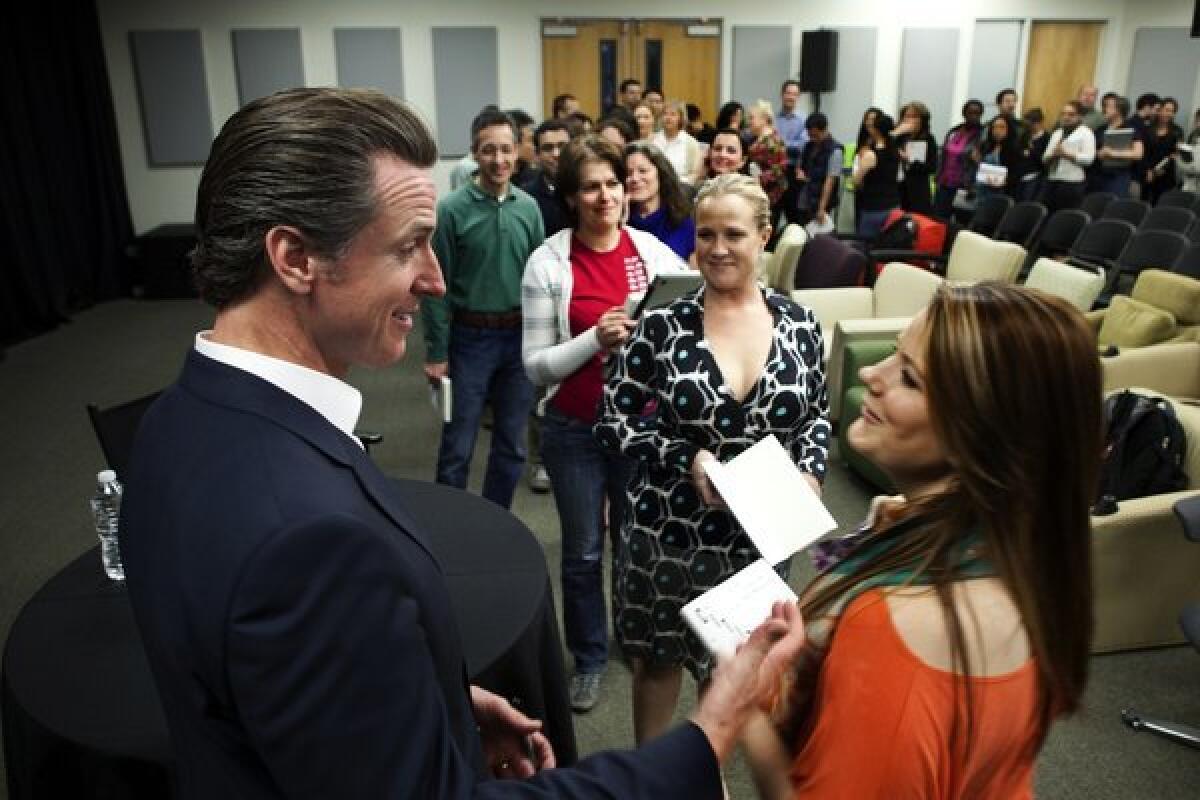

Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom chats with Linkedin employees during a book signing after being the guest speaker at an All Hands Meeting in Mountain View, Calif. More photos

Just a few years ago, Newsom, a Democrat, was on his way to political stardom as the big-city mayor who flouted state law and ordered San Francisco to grant marriage licenses to same-sex couples.

That controversial move led to years of legal wrangling and resulted in last month's Supreme Court decision that allowed gay marriage to resume in the state. He also launched the country's first universal healthcare initiative — three years before President Obama's program won congressional approval.

He survived a potentially career-killing affair with the wife of his campaign manager and close friend and later emerged as a leading contender for governor.

Then political veteran Brown jumped into the race. Facing weak poll numbers and a skimpy bank account, Newsom was left with few political options other than to run for an office he had once derided as "a largely ceremonial post … with no real authority and no real portfolio": lieutenant governor.

With all due respect to that office, anybody who holds it has a fate almost worse than death."— Larry Gerston, political scientist

"With all due respect to that office, anybody who holds it has a fate almost worse than death," said Larry Gerston, a political scientist at San Jose State.

The post has rarely been a springboard to anything. Since the state's birth in 1850, only two No. 2's have been elected governor. The last, Gray Davis, was recalled and replaced by Arnold Schwarzenegger. No lieutenant governors have become senators, either, or presidential candidates.

Will Newsom be able to defy historical precedent?

He clearly tries to keep a high profile. He hosted a short-lived talk show on Current TV. He wrote a book called "Citizenville," about the intersection of technology and politics. A political junkie who starts his day with Politico's "Playbook," the insider newsletter on Washington politics, he is a regular on local and national news shows, including "Meet the Press."

"Not a lot of lieutenant governors are on that show," he said, laughing.

Nearly every surface of his Capitol office is covered with photos of him embracing Democratic heavyweights: Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Ted Kennedy. The items on his desk, however, serve as reminders of his current political station: policy papers on pot legalization, sent by a drug research group, and a box of artichokes — a gift from California growers.

"These are the serious things we do in politics," Newsom joked as he opened the artichoke box.

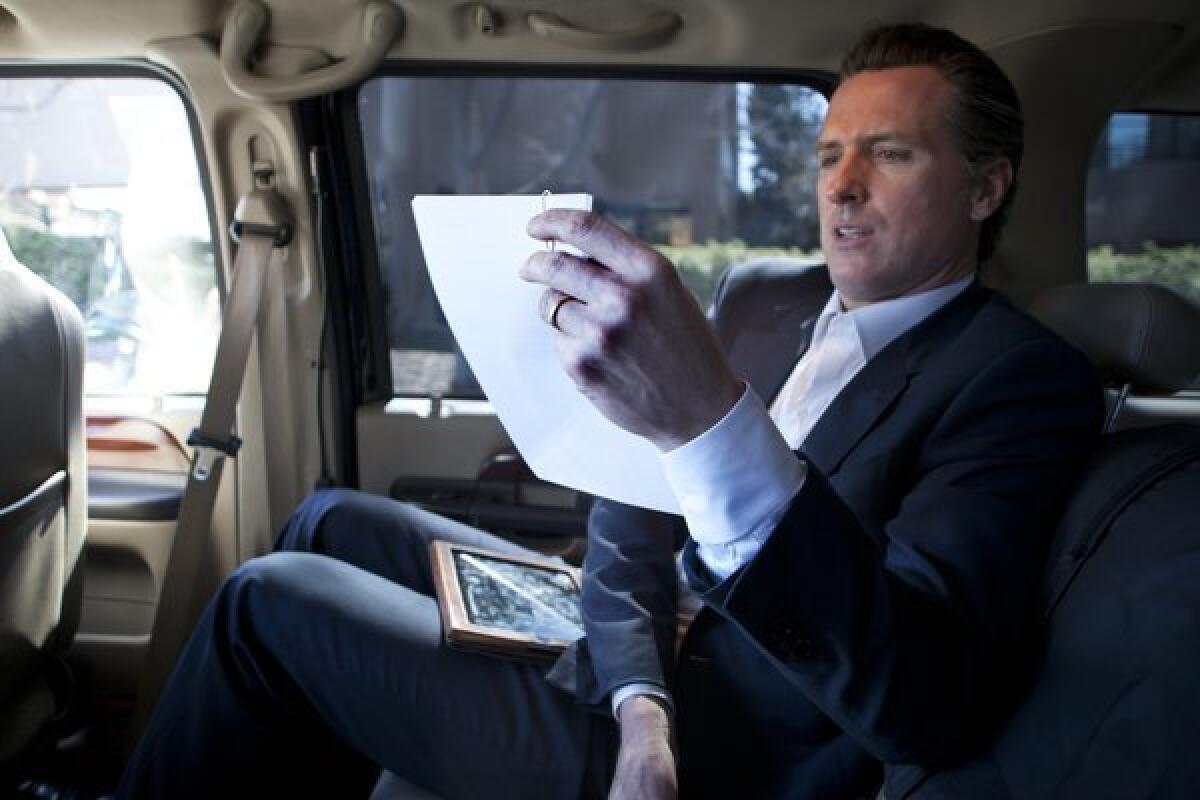

Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom works in his California Highway Patrol-driven vehicle between speaking engagements in Silicon Valley in February. More photos

Later that day, representatives from the California Asphalt Pavement Assn. met with him to ask that he use his clout to help push through legislation to fund infrastructure repairs. He told them that he didn't have much power. Although he chairs the state Commission on Economic Development, he said, the governor had yet to appoint enough members for the body to vote on anything.

"The good folks across the hall haven't been interested in appointing anyone," Newsom said of Brown's office. "It's only been two years…"

He admitted numerous times to disenchantment with his job and the temptations he faces as acting governor when Brown leaves the state. (Newsom is in charge again for the next two weeks while Brown vacations in Europe.)

"I'm not the guy who's going to appoint a Supreme Court justice or anything stupid. But there were moments when I thought, 'You know what, damn it, can I at least appoint the commission that I chair,'" he said. He paused before adding, "I'm not going to do it."

He did draft legislation to make his job part of the gubernatorial ticket — instead of an independently elected office — but he couldn't find any legislators to introduce it.

In one conversation, he cribbed a line from Thomas Edison: "I feel like I've succeeded in finding a million ways not to do something."

Being lieutenant governor does give Newsom a bully pulpit, however small.

From his perch on the governing board of the University of California, he railed against tuition hikes and the school's new logo, which he thought failed to respect the history of UC. The symbol was universally panned and later dropped.

He has repeatedly endorsed the full-scale legalization of marijuana — the only statewide elected official to do so, as he often says.

Sometimes he makes headlines — small ones — as acting governor. In April, he issued the tongue-in-cheek proclamation to correct a "glaring absence of agricultural products from the list of our officially adopted icons." For the remainder of 2013, he anointed the avocado as the state fruit, the almond as the state nut and rice as the state grain. The state vegetable: the artichoke.

Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom stops for lunch at Crepeville in Palo Alto after making an appearance on Fox Business with Adam Shapiro in February. More photos

The man with the movie-star looks and slicked-back hair is also a serious nerd.

He is rarely without a white legal pad — the byproduct of a boyhood struggle with dyslexia — where he scribbles extensive notes on state, national and international news. Once a week, interns take those notes and distill each topic into a single page and store them in binders. They do the same for the political and economic books Newsom marks up with comments and yellow Post-It notes.

The personal "CliffsNotes" help keep Newsom topical. Before a round of national interviews recently, he studied his notes on Syria, Benghazi and the Senate confirmation of the defense secretary. He has little use for the knowledge in his day job, however, because Brown never asks him for his opinions on anything.

Newsom and Brown have family ties that go back generations: Newsom's grandfather ran Brown's father's campaign for San Francisco district attorney; the younger Brown appointed Newsom's father to the bench.

Since the 2010 election, the two men haven't had a one-on-one meeting even though their offices are across the hall from each other.

The tension started during their short-lived battle for the Democratic nomination for governor, which Newsom pitched as a choice between "a stroll down memory lane" with Brown, then 71, or a "sprint into the future" with Newsom, then 41.

It was difficult to realize, 'I'm lieutenant governor.' And Brown appropriately reminded me of that."— Gavin Newsom

After Brown was elected to the top job and Newsom as his lieutenant governor, Newsom tried to carve out a role for himself. He asked Brown to create a council on homelessness and appoint him to the board that governs the state's nascent health insurance exchange, two areas where Newsom had distinguished himself in San Francisco. The requests went nowhere. Brown's office did not respond to The Times when asked for comment.

Newsom, who had co-founded 17 businesses, then spent months developing a 30-page plan to spur the state's sluggish economy. Brown ignored it and hired his own jobs czar

"It was difficult to realize, 'I'm lieutenant governor.' And Brown appropriately reminded me of that," said Newsom, 45.

He hasn't hidden his ambitions though. He told reporters in the middle of last year's election that he would like to run for governor in 2014 — careful to say he would do so only if Brown bowed out.

With the governor enjoying healthy approval ratings, an early retirement appears unlikely. Newsom now says he's focused on supporting Brown and on his own reelection to the position that pays $123,965 annually.

Asked last year whether he was satisfied with the job Newsom has done, Brown told the San Francisco Chronicle: "I think he's well within the tradition."

Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom chats with Rowena Bacher on the street in Palo Alto, Calif., in February. More photos

Newsom has a budget of $1 million to pay his small Sacramento staff and maintain two offices. He typically visits the Capitol about once a week.

He spends much of his time in the San Francisco Bay area, where he lives with his wife and their three children. He leases a desk in the city at a loft-style office building. When Newsom is not meeting with business executives, elected officials and labor leaders, he travels the state speaking to Chambers of Commerce, Rotary Clubs and other civic groups.

"He's gone from 24/7 to now trying to figure out what he's going to do next," said Derek Smith, a longtime friend. "I honestly don't know if he can do this job for another four years."

One day earlier this year, Newsom barnstormed the state, downplaying the influence of elected officials. Speaking to employees of the website LinkedIn, he talked about how social media and technology have empowered citizens to fix problems that would typically be left to government.

The world has shed "this idea that you have to be someone to do something…," he said. "You don't need formal authority."

Newsom ended the day in Los Angeles with Jimmy Kimmel, using his office as a punch line on the comedian's late-night show: "You wake up every morning, you read the paper looking in the obituaries for the governor's name. That's pretty much it."

Newsom then recalled the time in 2004 as San Francisco mayor when he ordered city staff to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples who had applied for them.

"The question for politicians here is fundamental: You can read the polls or you can change the polls," he said to cheers. "Stand up on the things you believe in."

It was the sort of talk you might expect from someone running for governor.

Follow The Los Angeles Times (@latimes) on Twitter

More great reads

In the U.S. illegally, she inspires a senator

See, this is why I did this. Because of some things she said."

Fighting cancer to see her son grow up

He knew I was sick but didn't know how to tell us he was worried."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.