Immigrants turn to job agencies for the American Dream

Employment agencies become gateways to the U.S. by playing matchmaker for Chinese-run businesses and cheap labor.

- Share via

Wedged between a travel agency and a hair salon off one of Monterey Park's busiest streets, Honesty Employment Agency has no English sign.

There one recent afternoon, three young men lounged on black leather couches, chatting in Mandarin about jobs in distant states.

"Dallas is very good, if you know a little English," said the owner, Mimi Chen.

"I'm afraid it won't work out, and I'll end up going for nothing," replied one man with spiky hair and a shy manner.

The phone rang, and soon Chen was niftily managing two conversations at once, a cellphone pressed to one ear, a landline to the other. She scrawled job listings in one of the notebooks stacked on her desk. Everyone calls her "Sister Chen."

"I have a stir-fry cook right here. He can do any job," Chen said before handing the phone to the cook for a quick interview with a restaurant owner.

Here in this bare room, where a map of the U.S. is one of the only decorations on the walls, a young man newly arrived from northeast China can find work washing dishes in Minnesota or Utah for 12 hours a day, six days a week.

Honesty — official name: Xin Xin Service — is one of at least a dozen employment agencies near the intersection of Garvey and Garfield avenues that are gateways to a hidden economy, supplying Chinese-run businesses around the country with cheap labor.

In an afternoon or two at the agencies, stories emerge of immigrant dreams that have dead-ended in short-term gigs as fry cooks, busboys, masseuses or nannies. It is a world that rarely intersects with mainstream America except through bargain foot massages or the General Tso's chicken served at small-town restaurants.

Some employers insist on a work permit or green card, while others will hire immigrants without legal status. In the lingo of at least one agency, "He has everything" means he has papers. "He doesn't have anything" means the job will be under the table.

While they wait, job seekers vent about unscrupulous bosses and exchange updates on their immigration cases, many of them involving asylum. The agencies deal in possibility but also its flip side.

Qiang Chen, 58, a veteran of the restaurant circuit who was waiting for a job in front of the Xing Xing Employment Agency on Garfield, shook his head and scoffed when asked if he ever received overtime pay.

"The bosses are bad. They should treat other Chinese well," said Chen, who has a green card. "Instead, it's Chinese taking advantage of Chinese. There's no job where you don't work at least 12 hours, from 10 in the morning until 11 at night."

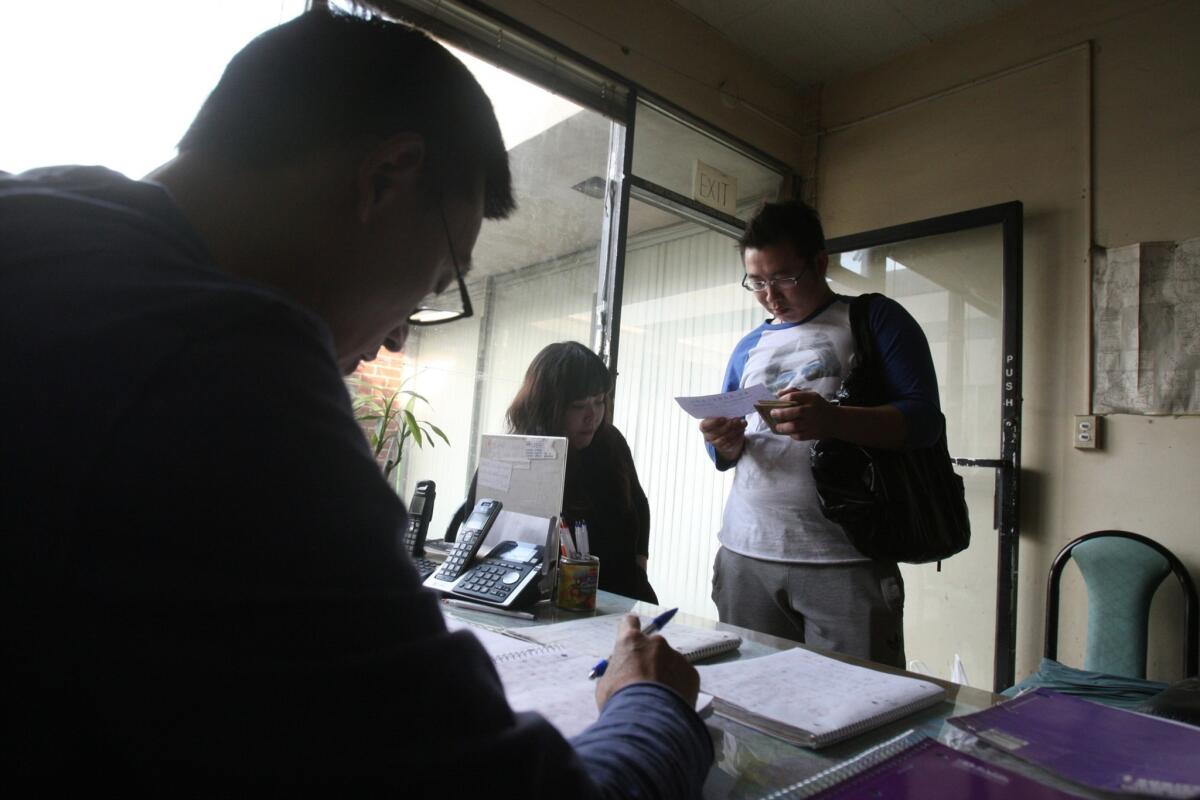

Genxing Qin (left), 52, assists a couple from northeast China at Xing Xing Employment Agency on January 27, in Monterey Park. The agency assisted the couple, who are from Liaoning, China and did not wish to give their names, in getting a job at a massage parlor in Phoenix. Genxing Qin helps Chinese immigrants find jobs at small businesses around the country. Xing Xing is one of at least a dozen employment agencies at the interesection of Garfield and Garvey Avenues in Monterey Park. More photos

Everything a Chinese immigrant needs can be found on this corner — an $8 haircut, the bread and noodle dishes of northeast China, dried sea cucumber to treat high blood pressure. A two-minute phone conversation at one of the employment agencies can be enough to secure a job.

A few years ago, Monterey Park cracked down on the agencies for occupying prime storefronts reserved for retail establishments. Job seekers spilled onto the sidewalks, chain-smoking as they waited, said Monterey Park City Manager Paul Talbot.

Now, most agencies are located upstairs or deep within shopping plazas, in compliance with zoning laws. About 20 are registered with the city.

At Xing Xing, handwritten signs advertised for a driver in Tennessee — paying $3,000 a month — and a fast-food cook in Texas, for $3,300. Another agency listed jobs in New Mexico, Utah, Nebraska, Colorado and Wisconsin. Out-of-state jobs pay more than local ones and often include room and board.

Workers foot the referral fee — typically, $40 for restaurant or massage jobs, $80 for domestics. Transportation costs are also the worker's responsibility, unless the job lasts at least six months.

"You can call from any part of the country to get a nanny or a restaurant worker sent to you," said Xiaojian Zhao, a professor of Asian American studies at UC Santa Barbara who has studied the employment agencies. "They are like labor distribution centers for the ethnic economy."

There's no job where you don't work at least 12 hours.”— Qiang Chen

Prosecutions of Chinese employment agencies are rare. But in January, agency owners in Houston were arrested on federal conspiracy charges, accused of providing jobs to immigrants from Mexico and Central America who were not authorized to work in the U.S.

U.S. Department of Labor officials have visited the Monterey Park employment agencies to distribute information about workplace laws. Federal investigators have found that some Chinese restaurants that employ immigrants violate overtime and minimum wage requirements by paying a flat salary, said spokeswoman Priscilla Garcia.

The ease of finding work gives immigrants a measure of power. They can walk away from an unsatisfactory posting and return to Monterey Park to try their luck elsewhere. The wages, low by American standards, are still more than they could make in China.

"Is room and board included? How much is the plane ticket? $200? One way? OK, that works," said a thick-set man in a yellow T-shirt and jeans, on the phone with a restaurant boss outside Xing Xing.

The man, a recent immigrant from northeast China, had just scored a job in Pennsylvania, though he said he had no idea where that was.

Nearly all the job seekers are Chinese, but some Latinos have discovered the agencies. On a recent afternoon, a trio of young Guatemalan men walked out of Yang Guang Employment Agency on Garfield, soon to start as dishwashers at a Chinese restaurant in West Covina.

"We have been the portal, the Ellis Island, of Asian immigrants for 30 years," said Talbot, the city manager. "We see people walking down the sidewalk with suitcases. They've just landed. I don't know how they get here from the airport, but they get here."

Of the three employment agencies in a small shopping plaza off Garfield Avenue, Chen's is by far the busiest.

Mimi Chen, 43, is a native of Hunan who owned a chain of nursery schools in China. Her wavy bangs and large glasses are old-fashioned, but her wardrobe includes flashy staples like a tight turquoise minidress and a zebra print cardigan. She says her clients came to the U.S. to make money, and she helps them achieve that goal.

We have been the portal, the Ellis Island, of Asian immigrants for 30 years.”— Paul Talbot

"I will help them with their problems and create a road for them to travel," Chen said. "It's not easy for new immigrants."

Chen said there is nothing illegal about her middleman role. If bosses violate labor or immigration law, "that's their problem," she said, while workers are free to refuse the jobs.

"If you want to go do that job, go do it. If you don't like it, I'll help you find something else," she said.

Bosses are blunt about their requirements: only women, preferably pretty women, not too old, not from that province. Many deals are finalized with hurried phone interviews, so both parties rely on Chen's judgment. She dispenses advice as freely as jobs, often in a schoolmarmish scold, counseling immigrants to lower their expectations.

"If this store is so great, why would they hire inexperienced people?" she told a woman hoping to break into the massage business. "So go there and learn something, then go somewhere else."

Chen's matchmaking is not limited to jobs. For $2,000, she will venture into affairs of the heart.

After several hours of waiting, the spiky-haired young man approached Chen's desk. He would give only his last name, Miao, because he had not yet received the work permit typically issued to asylum applicants.

I will help them with their problems and create a road for them to travel.”— Mimi Chen

Since coming to the U.S. from Hebei province a year ago, Miao has waited tables at Chinese buffet restaurants in Nebraska and Owasso, Okla. The 12-hour shifts, for tips only, were too grueling. He wanted to try his hand at massage.

"Can I get my wife and kid over here? If I don't pass my asylum interview, this will all be for nothing. Should I take this time to learn English?" Miao asked. But Chen was on the phone again and didn't reply.

In Monterey Park, Miao stays at a "family hotel" — a boardinghouse, where the going rate is $10 a night to share a room with many other immigrants. From there, he can hop on a plane or a Greyhound bus at a moment's notice. He studied hotel management in college and would like to train as a nurse or electrician.

"Life is simpler in the U.S. In China, it's all about guanxi," Miao said, referring to the personal relationships that are currency in Chinese culture. "You can't get a job without guanxi."

A week later, he had given up on switching to massage. He found a job, through another Monterey Park employment agency, and was headed to one more buffet restaurant, this time in Denver.

Follow Cindy Chang(@cindychangLA) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Turning to Native rain dance in time of drought

In a small town, when you call a rain dance, word gets around.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.