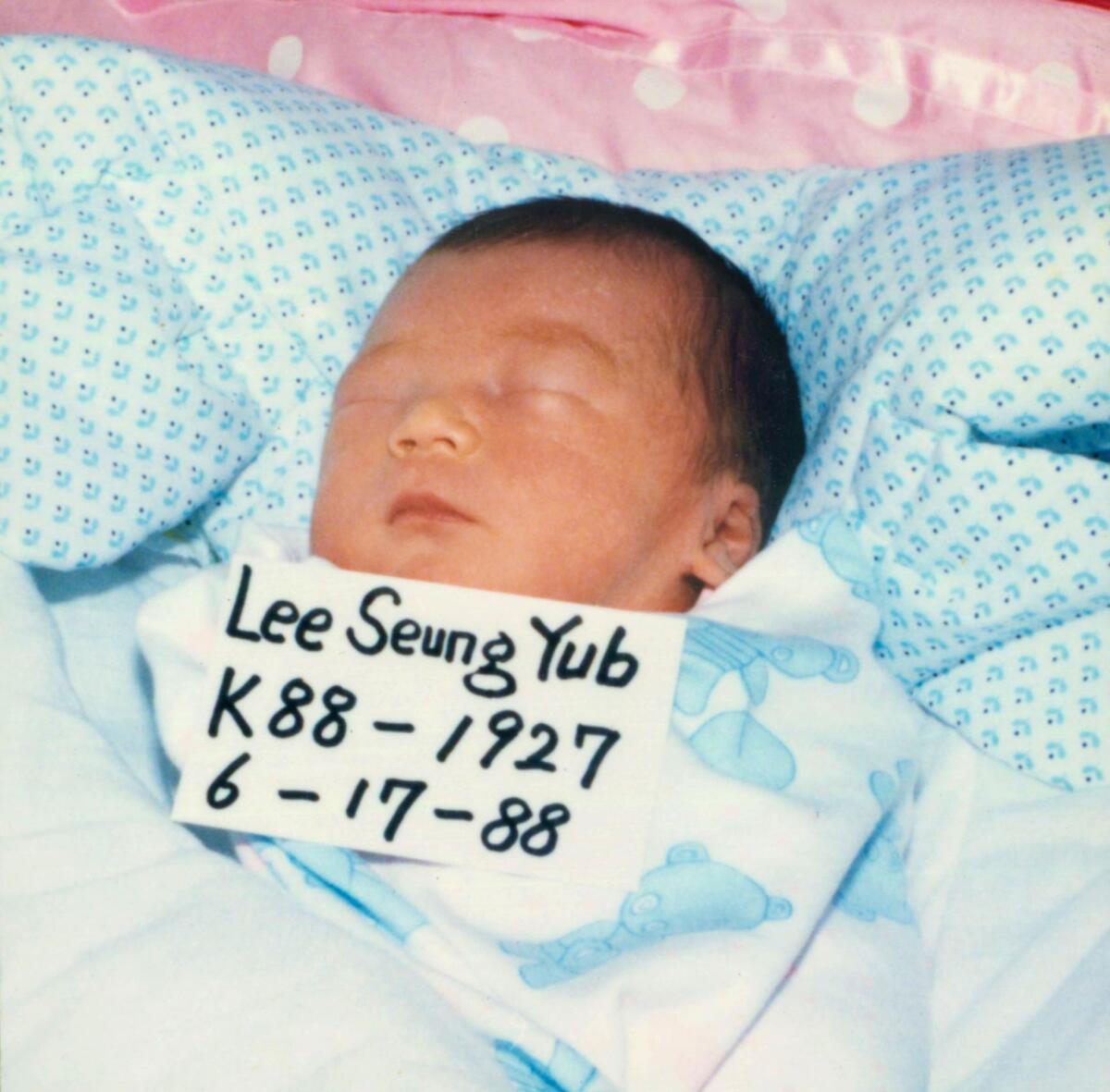

An adopted son discovers more than he expected in return to S. Korea

A reporter had envisioned simply saying ‘thank you’ to his biological mother. But seeing her pain over giving him up and her shame at being a single mother, it was not so simple.

- Share via

T

wo knocks. I swallowed hard. A middle-aged Korean woman with dimpled cheeks, her hair held back by a tiny blue butterfly clip, peeked around the door.

"Annyeonghaseyo," I said softly, timidly — my awful Korean accent worse than normal.

"Annyeonghasey…" Her voice cracked. She couldn't finish the word for hello. She began to cry, her sobs almost a moan, and locked her arms around me. She repeated something faintly.

"She's saying she's sorry," the social worker who was with us translated. "She said she's really, really sorry."

As I listened to 25 years of shame spill from somewhere deep inside her, it was impossible not to break down with her.

"I missed you," she said. "I've never forgotten you."

I would not cry again during my 3 1/2-hour meeting with my biological mother.

But in those moments I cried because I understood the depth of her pain — and I knew I was helping to relieve it.

On my application for a program that brings Koreans adopted abroad back to the land of their birth, I ranked "Search for your birth parents if possible" the lowest on a scale from one to five.

On a survey, the adoption agency that organizes the annual trip asked: "Do you want to pursue a possible birth search?" I circled "Don't know."

Unlike many other adoptees, I have never been all that curious about, much less troubled by, my adoption. My parents, who are white, handled the topic so smoothly that I don't remember ever having a formal conversation about it. I got a good education, I have a good job and I'm surrounded by loving friends and family. I know how fortunate I am.

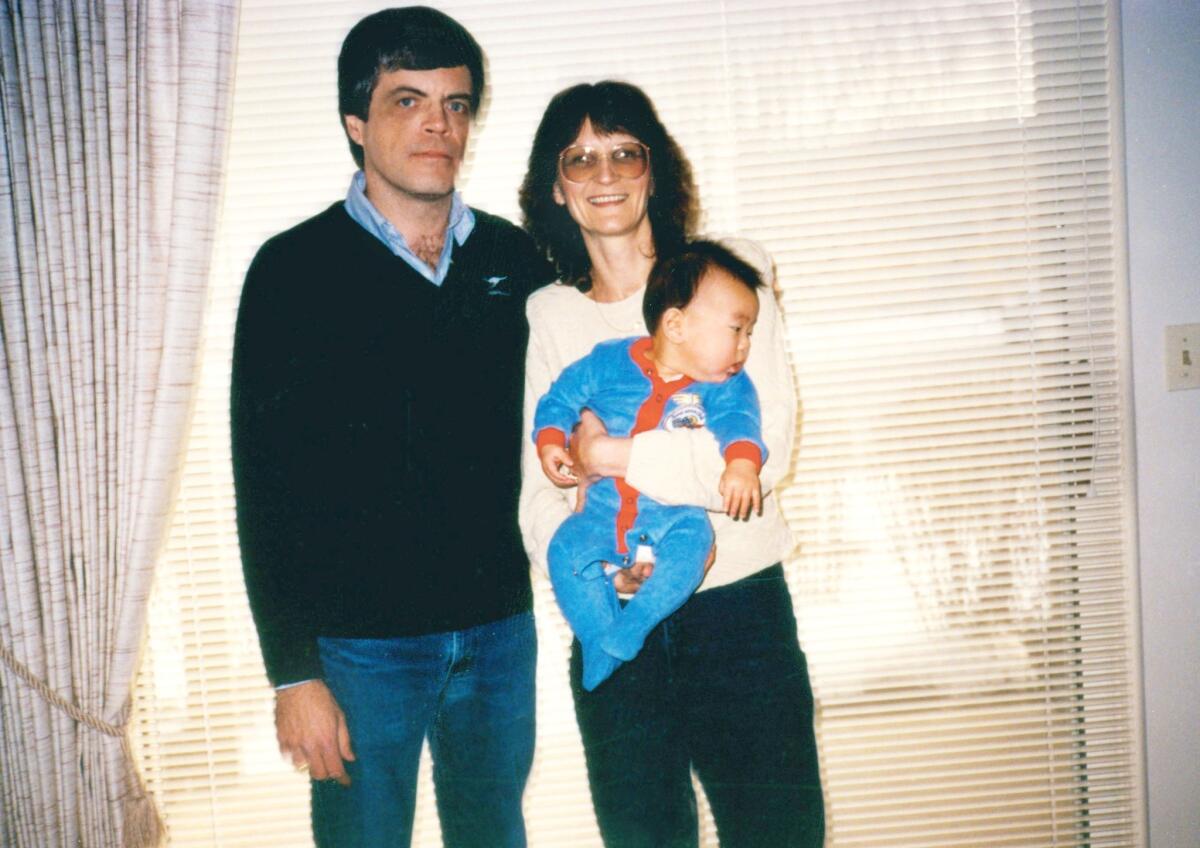

Matt Stevens is held by his parents, Jim and Jan. They were supportive of his trip back to South Korea and of him meeting his biological mother. (Family photo) More photos

But after taking an Asian American studies class in college, joining an Asian journalism group and just living close to Los Angeles' Koreatown, I wanted to learn more about the country I last saw when I was 4 months old.

So I applied for the Happy Trail in Korea program, organized by my adoption agency, Holt Children's Services. In July, I joined 16 other Korean adoptees from five countries, ages 19 to 39 — many, like me, visiting South Korea for the first time.

During a 12-day marathon, this eclectic group became as tightknit as any set of summer campers ever could.

We cheered one another on as together we broke boards during taekwondo, drunkenly sang Britney Spears songs at karaoke and most of all, swapped stories about the things we had in common.

But each of us came to Korea for a different reason. Some wanted a free international vacation. Others were searching for their identity.

Some of the 17 told the agency that they didn't want to search for their parents at all. Others longed to find their families, but struck out. Only six of us met our biological parents during the trip.

Two French sisters, Camille and Marion, were 4 and 6 when their father dropped them off at the agency, promising that he would be back soon. Marion, now 30, still remembers what the building looked like.

Their father never came back — until their meeting this summer.

When Camille and Marion returned from their reunion, they passed around baby pictures — ecstatic to finally have the little images of themselves so many of us take for granted. Camille playfully tried to hide one photo she thought made her head look too round. Then she summed up her meeting and the common thread in each of our experiences.

"It was like swimming, swimming, swimming…"

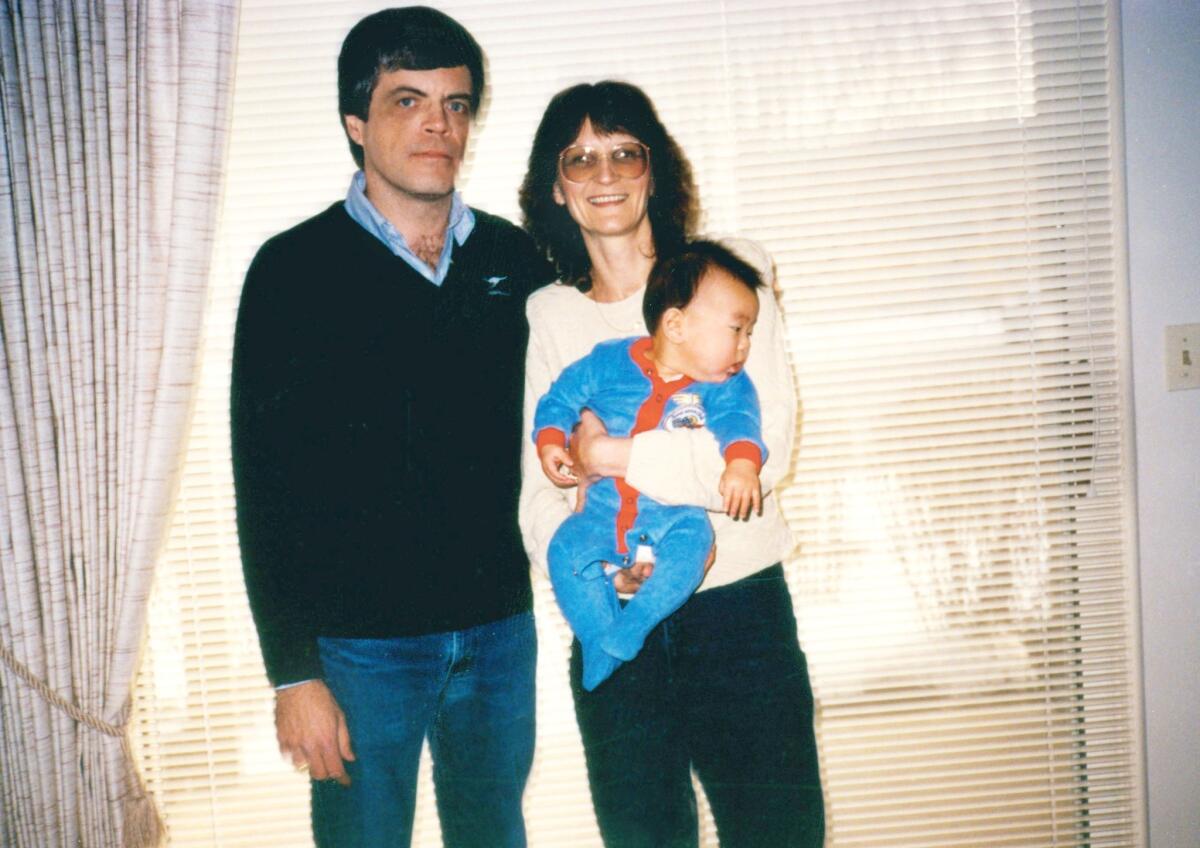

That same day, I returned from my own meeting with my biological mother. A friend I call my "Seoul mate" delicately slipped her hand over mine. She furrowed her brow, and felt she had to ask: "Are you OK?"

After the hug at the door, my biological mother and I took seats on opposite sides of a small oval table. On the lime-green wallpaper, birds hovered near a tree with wavy branches, making the room feel a little like a children's nursery.

I had misjudged the magnitude of this meeting — both for my biological mother and for me.

She scooted her chair around the table so she could snuggle up next to me. She began massaging my arm up and down, up and down. She grasped my hand and held on for most of the first hour. She told me her name was Lee Jung-soon, and I told her my name was Matt Stevens.

I had agreed to the reunion so I could simply say "Thank you," and perhaps make one mother worry a little less. Then I figured I would move on.

But I had misjudged the magnitude of this meeting — both for my biological mother and for me.

As the conversation sputtered along, it became increasingly clear that this was a life-changing day for my biological mother. She would later tell me that since we met, every day had become happier for her.

I told her how selfless she was to choose adoption. I thanked her for her choice and pointed to a piece of paper on the table with pictures of my family taped to it.

But that only unleashed a new round of sobs. "I would never have imagined that you would have ever looked for me," she murmured. "Thank you for accepting me."

I always knew the boilerplate facts in my adoption file: My biological mother got into a relationship and when she was five months pregnant, the man told her that he was married.

Is it true that you have never resented her, never blamed her?"— Esther Kim, social worker and translator

What documents in my file called "adverse circumstances" made it too difficult for her to raise me on her own, so she gave me up for adoption. The file also told me that I had three half siblings: two on my father's side, one on my mother's.

When I asked about my biological father and my half siblings, my mother remained troubled by her own "sinful past."

"She's asking again, and this will take some time, no matter how many times we repeat and tell her," said Esther Kim, the social worker. "She was asking, 'Is it true that you have never resented her, never blamed her?' "

In Korea, single motherhood still carries a heavy stigma and many people remain more reluctant to adopt than in other parts of the world. The Confucian society still deeply values bloodlines and keeps detailed records of family ancestry.

Still, more than 160,000 Korean children have been adopted internationally since the Korean War ended in the 1950s. The majority, like me, were adopted in the United States.

The practice peaked in the mid-1980s, a few years before I was born. Today the number of Korean international adoptions into the United States stands at a few hundred per year.

Rachel Taylor, left, and Matt Stevens pose for a picture. Taylor, whom Stevens calls his "Seoul mate," was among the program participants who helped Stevens process his meeting with his biological mother. (Rachel Taylor) More photos

In South Korea, reality TV shows that attempt to reunite separated families routinely feature adoptees.

My biological mother told me that she watched such a show, and "every time I saw it, I would wonder if you'd ever come up."

She felt guilty about her past, and I felt guilty that I didn't have the same feelings for her that she had for me. She had thought about me almost daily for years. Because I have always been happy with my adopted life, I had not looked for her until now.

Today, when I listen to the recording I made of our meeting, I tear up. I'm ashamed of the man talking in stilted English to his biological mother like he's addressing a child, filling every silence with words of praise and forgiveness.

My biological mother asked me for my phone number and to see me off at the airport. I said talking by phone would require a translator, and planning another meeting would be too complicated. We would simply write letters using the agency as an intermediary, as it advised.

When would I come back? I promised that I would see her again, but couldn't guarantee exactly when.

The woman who brought me into the world wanted to touch me, hold me. At one point, she noticed that my shoe had come untied, and promptly bent down to tie it for me.

As we walked back to the hotel, a drizzle began to fall and she unfurled an umbrella. In an instant she had me tucked into her chest. "I will not let even one drop of rain fall on your head," she said.

And as we stood in the lobby getting ready to say goodbye, she peered up at me and grasped my hand, her eyes watering again.

"Be healthy, be happy," she whispered before kissing my palm. "I love you."

I couldn't quite meet her gaze.

Then I said, "I love you too."

Follow Matt Stevens (@MattStevensLAT) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Brazilian sees museum as 'the Disney of the future'

We are building the...Disney World of culture, the intellect, the environment and research."

A strong voice in Louisiana's Cancer Alley

The guys who work in the plants will tell you they know it killed their dad."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.