An African American farmer’s Central Valley dream

- Share via

When his mother’s health was declining, Dennis Hutson moved to Allensworth in California’s Central Valley. The town, founded in 1908, was created on the principle that African Americans could own property, run their own town and live peacefully while pursuing the American dream. Population 471, the town is now just 5% African American.

It’s the kind of place where everyone knows everybody. Some cite the demographic shifts of African Americans moving to cities, and others the closure of the Allensworth railroad stop, for the economic downfall of the area. There is not even a service station or corner store in the town.

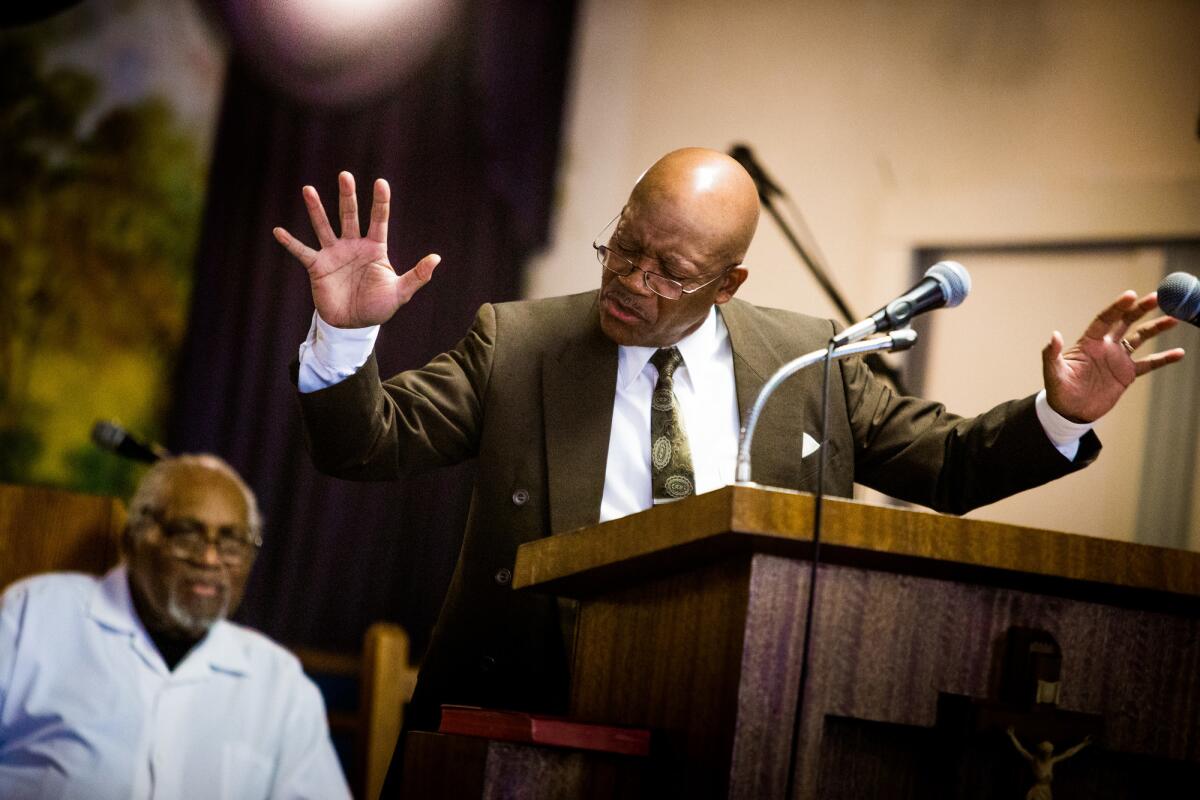

When his mother, Nettie Mae Morrison, moved to Allensworth in 1979, Hutson began visiting. He was amazed by the poverty and lack of economic development. A Methodist preacher and Air Force chaplain, he said God spoke to him and told him to be a positive change in the community.

Since then, he has purchased a 60-acre farm, hired several African American farm hands, and is now on his way to owning a sustainable, organic farm. In a country in which less than 2% of farmers are African American, Hutson hopes to provide a boost to this once-thriving town.

He is doing it to honor his late mother (“the unofficial mayor of Allensworth”) and to provide economic opportunity for his African American brothers and sisters.

After a morning of work on his farm and checking his fields' water levels in the evening, Hutson rests. His wife and most of his family live in Las Vegas. He jokes that all of his decades in the Air Force and tours around the world helped prepare him for this — his most remote posting. His wife plans to join him within a year, when the farm is more functional, and they will build a home.

In the evening, Hutson drives to the edge of his farmland to visit his mother’s grave.

“I think she would be very pleased and proud to see what we have done here,” he says. “I think that part of the reason that she hung on so long was because she wanted to see the progress here and that someone other than herself was working for this community.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.