Great Read: Tragedy shapes a South L.A. playwright’s artistic life

- Share via

The bullet screamed out of the barrel of a silver-plated handgun, tearing through his left eye, his nasal canal, the optic nerve in his right eye. He fell to the barroom floor.

Everything was dark and he waited for death. So did the paramedics; he heard them say he probably wasn’t going to make it.

Four days later, lying in a hospital bed, he still couldn’t see. He was afraid he was going crazy, that the trauma of being shot made him imagine he was blind. Then a doctor sat at his side and explained: Surgeons had been forced to remove his left eye. The optic nerve in his right eye was severed.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Lynn Manning: A headline on an article in the Nov. 14 Section A about playwright Lynn Manning said that violence in South L.A. took away his sight. The shooting that resulted in the loss of his sight occurred in Hollywood. —

------------

“It will no longer work,” the doctor said. “You’ll never see anything again.”

Lynn Manning, tall, black, strikingly handsome and 23 at the time, had been raised amid relentless chaos in South Los Angeles. He’d dreamed he could alter the course of his life by devoting it to art and becoming a painter.

“Growing up, I had developed a habit of always preparing for the worst,” he says, his measured, resonant voice evoking a bluesy disc jockey whose words come wrapped with a professorial air. “Even before the shooting I’d thought, ‘Since you love painting so much, how would you survive if it was taken from you? If you couldn’t see?’

“It was hard for everyone around me to believe, but I looked at it like this wasn’t the worst thing that ever happened.”

He’d been blinded, but soon he discovered that there was more than one kind of art. Much more. Over time, the stage would become his canvas, and the city where he was nearly killed his muse.

::

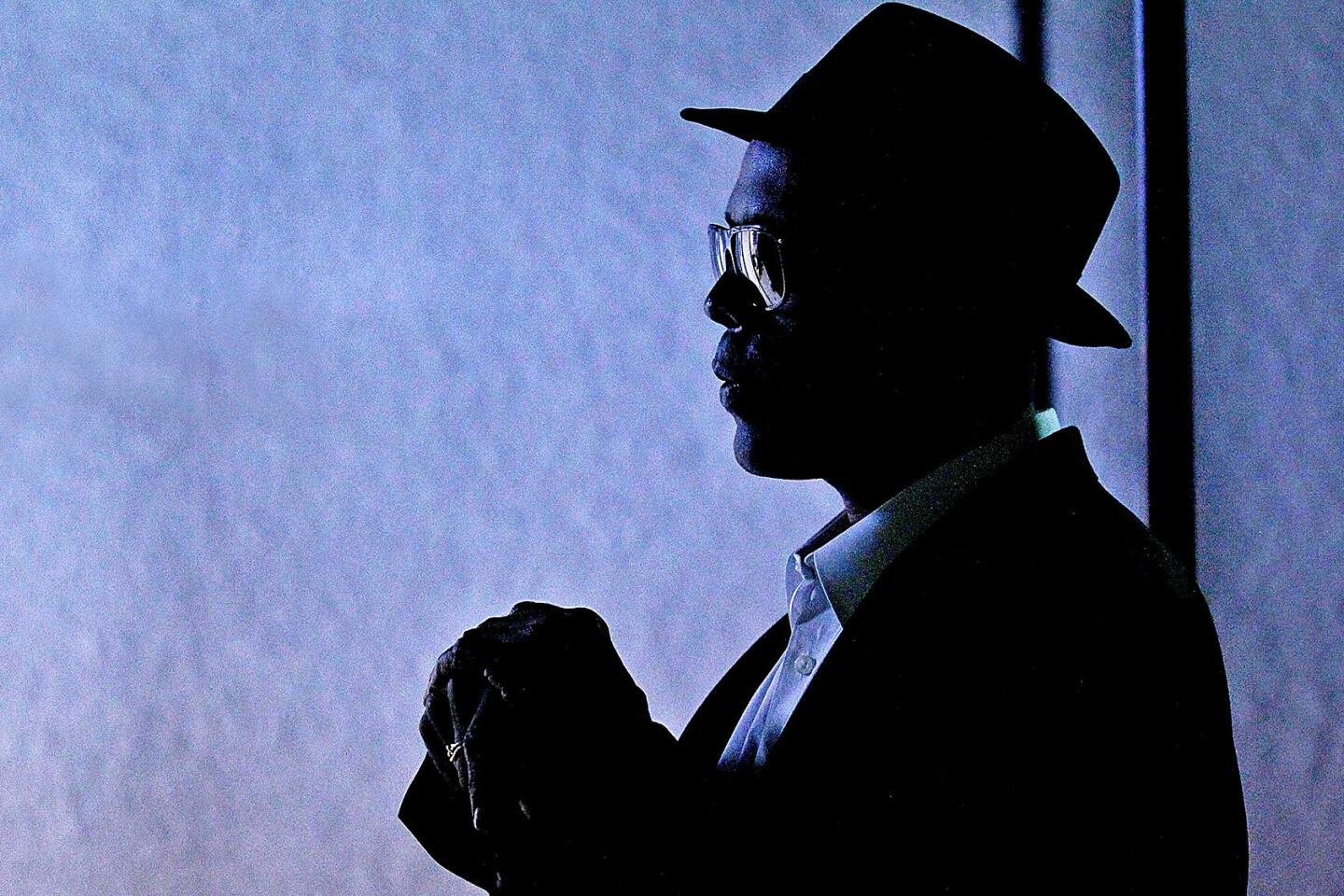

Thirty-six years after the shooting, Manning is a vital part of Los Angeles’ cultural landscape: a poet, actor and playwright whose work leans on sharp perception and unflinching social commentary.

He says he comes up with some of his material during regular rounds at the darkened H.M.S. Bounty, an old-school, mid-Wilshire jukebox bar full of white, black, Latino and Asian regulars. “Hey big Lynn! … Welcome back, my man!” they call out when he walks in.

He perches on a stool at the long counter and orders grilled pork chops and a house Pinot Noir. He flirts with the waitresses and talks hoops and politics with Andy, Shin, Lawyer Bill or others from his wide cast of barfly friends.

The Bounty was the recent location of his annual “Rebirth Day,” which celebrates the shooting’s anniversary and the good and bad that came after it, from the poetry to the plays to the pair of failed marriages.

“At heart, I’m a homebody,” says Manning, who lives alone and walks with a carbon fiber cane five blocks from his small apartment to the bar. “Los Angeles is the central character in my work: all that tension, all those issues being worked out.”

And he has given back to the city, as the co-founder and artistic director of the Watts Village Theater Company, the only professional acting group in one of L.A.’s most impoverished corners.

He knows the area well. When he was 7, growing up in a tough South L.A. neighborhood near USC, his life was upended by a vicious argument. With a butcher knife, his mother stabbed and nearly killed his stepfather, sending Manning and his handful of siblings into the clutches of foster care.

What followed was about a decade of nonstop uncertainty. He ended up living in six foster homes — several near Watts — and attending nine schools. He suffered vicious treatment.

What saved him was art. He could spend hours playing with color, painting faces and geodesic shapes. As early as grade school he was selling pencil drawings of Batman and the Beatles for a few dimes.

“I lived for that visual sense,” he says. “It took me away from harsh reality.”

After high school, he had a goal: move to Paris and become a painter. He got a job as a counselor at a group home and took art classes at Los Angeles Community College. Whip smart, with a soft Afro and an easy smile, he cut quite a figure at his favorite Hollywood drinking spot: The Waterhole #5 on Vine Street.

It was there that he went on the evening of Oct. 25, 1978, celebrating a work promotion in his white Panama hat.

A stranger approached; Manning and the man fought. The man skulked from the bar — then returned, carrying a silver-plated .32.

During his recovery, Manning vowed not to feel shame or self-pity. Within a year, he’d learned the basics of Braille, mastered the sweeping cadence of walking with a cane, discovered new ways to organize his apartment so he wasn’t pouring laundry detergent instead of oatmeal into his cereal bowl.

There were setbacks, of course. Hard falls. Times he got lost walking the city or taking its buses. Once he stumbled into a busy Hollywood intersection, cars whizzing by so terrifyingly fast that he wasn’t sure he’d make it to the other side. When he did, just barely, a stranger drove up and offered a ride.

“I took that ride, something I wouldn’t have ever done before,” he says. “An important lesson: As determined as I was to do things my own way, I was going to have to learn to sometimes rely on people. I was going to have to learn trust.”

At the Braille Institute on Vermont Avenue, he took judo, and soon enough was aiming for a black belt and winning international competitions for blind martial artists.

He enrolled in a poetry class, overcoming his stage fright by reminding himself that if he could do judo blind, he could do just about anything.

By the early ‘90s, he’d become a popular mainstay on the city’s booming spoken-word poetry circuit — riffing free-form, autobiographical verse — sometimes darkly painful, sometimes sweet, often limned with humor.

“I just needed to hear one poem from him and I recognized that this was an enormous talent,” says Irene Oppenheim, a local playwriting teacher who took Manning under her wing. “He wanted to get into the world of plays.”

His breakthrough came when he adapted a play by 19th-century German playwright Georg Buchner into “Private Battle,” a critical look at racism and poverty through the lens of an African American soldier who grew up in South L.A.

“He started taking off,” Oppenheim says. “The play was really good. We took it to New York and he began to get a reputation and with that he was on his way.”

His most popular one-man show, “Weights,” centered on the shooting. Eventually he performed it in theaters from Los Angeles to Edinburgh to Adelaide, Australia.

During the play, Manning stands facing his audience, broad shoulders thrust back. When he takes his sunglasses off, other than the fact that his eyes fix on nothing, there’s no sign of the shooting, no sign of the bullet that remains lodged in his skull. He speaks of his blindness, and calls it a gift.

“In the absence of that vastness, that visual feast, I came to recognize the overwhelming distraction that sight had been. I had never noticed that sound moves the way it does, or feels the way it does. And what about this pulse, this radiation that flows from all things? And the smells! Good God! The smells! Who knew such sensory lushness existed in this more immediate realm. Blind people knew. Blind people had to have known all along.”

::

In 1996, determined to bring live theater to the neighborhoods of his youth, Manning and fellow African American actor Quentin Drew formed the Watts Village Theater Company.

Drew died nine years later, of cancer, but the group kept going, surviving just barely at times, throughout nearly two decades.

Cobbling together grants and donations to pay for professional actors, it has put on 25 full-scale plays, including works by Shakespeare and other masters adapted to fit story lines that resonate in South L.A. Lacking a permanent stage, its performances have been held at a train stop, at Jordan High School, the Watts Towers and inside a small gym at the Mafundi Institute, created in the aftermath of the 1965 riots.

Nothing has come easy. Audiences can reach nearly 100, but sometimes dwindle to six. “People have this fear of Watts, it’s hard to get people to come,” Manning says.

He refuses to give up, reminding anyone who’ll listen that the scarred community is also thick with stories that need telling through theater — a determination that has drawn plenty of admirers.

“He connects the white world, the hip world, the disabled world, the Latino and black and Asian world,” says Oliver Mayer, associate professor of dramatic writing at USC. He works “through the lens of Los Angeles, often through its violence — since violence is something that so affected him.”

At the Watts Coffee House on a recent Sunday evening, Manning sits in a small audience just before the start of the company’s latest play, “Follow,” which tells the story of a mixed-race gay couple raising a foster child and planning to wed, all while dealing with family and religious prejudice.

“We want to make people a little uncomfortable,” he says, placing his black cane beneath a plastic seat. “Move them to think beyond limits.”

The lights dim but he can’t tell, so he keeps speaking for a while. Then the audience quiets and an actor walks slowly to the stage, his footsteps soft against the carpet. Lynn Manning smiles his easy smile. He knows that the show is about to begin.

Twitter: @kurtstreeter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.