A closer look at test scores for English learners, magnet schools and charters

- Share via

More than three million students across California traded in pencils for computers to take their standardized tests last school year.

You might have read about the statewide results of the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress: More than half of the state’s public school students in grades 3 to 8 and 11th grade failed to meet benchmarks for college readiness. The test is new and considered harder than previous ones — and scores did increase from 2015, the first year scores were reported. But they remained low — and certain groups, such as black students, lagged behind.

Some schools and districts performed very well. Some improved greatly from one year to the next.

Across the Los Angeles Unified School District, 39% of students met standards in English and 29% in math.

At Wonderland Avenue Elementary School in the Hollywood Hills, whose students mostly are white and Asian, 84% of non-magnet students met English standards, and 83% met math standards. The school’s scores are higher still if you factor in the gifted magnet. Principal Sean Teer attributed some of the success to a new math program called “cognitively-guided instruction” that encourages students to create their own strategies for solving problems.

The tests are aligned to Common Core, a set of standards that are supposed to emphasize critical thinking and in-depth learning over rote memorization.

Though tests do not tell the full story of what’s happening in the classroom, the scores can be helpful in assessing the kind of education that different groups of students are receiving.

Learn more about this year’s test scores and look up your school at www.latimes.com/test-scores-2016.

Here’s a closer look:

Magnets

Students in L.A. Unified’s magnet schools performed far better on state tests than did students at other district schools or charters.

The district often touts magnets as examples of academic excellence, especially in comparison to charter schools. Part of its plan to maintain enrollment is to increase the number of these themed schools.

But the composition of test-takers at magnet schools does not reflect the district as a whole.

The magnets that got the highest scores are the gifted, highly gifted and high ability schools, comprised entirely of students who must meet certain requirements, which can include high scores on this state test. Other magnet schools accept students based on a complex lottery system that doesn’t take academic performance into account.

“This why the district’s strategy is problematic,” said UCLA education professor Pedro Noguera. While the district criticizes charters “for creaming off more privileged kids,” he said, magnets do the same.

The magnets without such entry requirements still performed better than independent charters or other L.A. Unified schools, but by a smaller margin.

At Downtown Magnets High School, a campus comprised of two magnets, principal Jared DuPree says his schools’ high pass rates — in the 90s for English at both schools — came thanks to a strategy of targeting struggling students. “We celebrate the data but we’re going to use it as a foundation to reach this utopian goal” of making sure 100% of students meet the standards, he said.

Not all magnet schools performed better than the district’s neighborhood schools. And compared to charters and the district as a whole, magnet schools have lower percentages of test-takers who are English learners, students with disabilities and students eligible for free and reduced lunch, a poverty indicator, according to L.A. Unified.

Magnets also had a lower percentage of Latino students taking these tests than the district as a whole, and there were a higher percentage of black, Asian and white students among magnet test-takers than in the district as a whole, according to the school system.

L.A. Unified does need to do a better job recruiting high-needs students to magnets, said Keith Abrahams, the district’s executive director of student integration services.

“Every child in the city needs to understand they can go to a magnet program,” he said. “My gut tells me that some families believe that they can’t.”

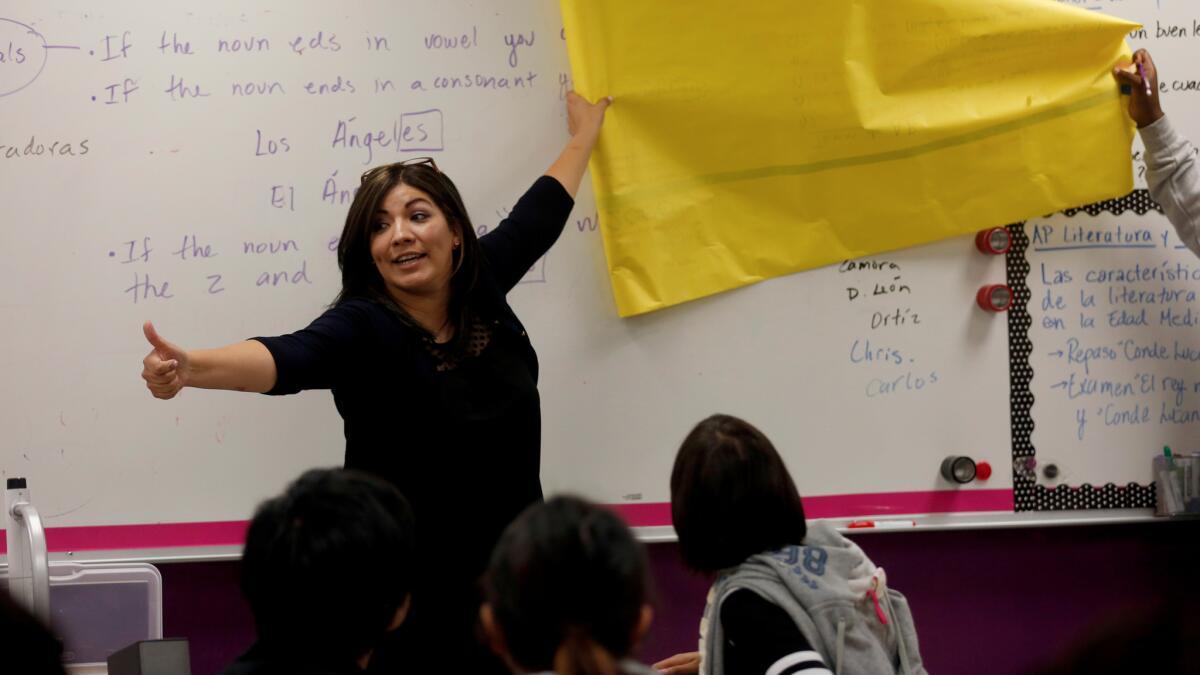

English learners

English learners as a group scored low on the test. In California, 13% met English standards and 12% met math standards. That’s a slight improvement over 2015, when 11% of English learners met both English and math standards.

In L.A. Unified only 4% of English learners met English standards and 5% met math standards. L.A. Unified English learners are more likely to be low-income than those in the rest of the state, which puts them at a higher risk for learning disadvantages, said UCLA education professor Patricia Gándara.

One problem is that the tests were designed for fluent English speakers, so it’s hard to say what the students don’t understand — the questions or the actual test material, Gándara said. And once English learners prove they have a mastery of the language, they’re moved to a different category called “Reclassified Fluent English Proficient,” which usually scores higher than the district average on state tests.

In 2015-16, there were 1.37 million English learners in California, over one-fifth of the total public school population. In L.A. Unified, about 165,000 English learners make up just over a quarter of the enrollment.

In some cases, Spanish speakers could take the math test in a stacked form, with the questions and answers listed in both English and Spanish, and some other tools were available, such as glossaries in multiple languages.

In L.A. Unified, 49,940 English learners took the math test, and about 1,800 had access to the stacked tool, though it’s unclear how many used it, spokeswoman Barbara Jones said in an email.

Some teachers in the district feel that they have not received enough training in how to teach Common Core standards, which require deep conceptual understanding, to English learner students, Gándara said.

Training around 30,000 teachers in Common Core and English language development standards “is a huge challenge for a school district like ours,” said Hilda Maldonado, executive director of L.A. Unified’s multilingual and multicultural education department. “They’re all doing double duty in my opinion. Everybody’s working hard at learning two things at once.”

One problem for these students is that during English class, some schools concentrate on teaching English learner students the language rather than concepts of literacy such as finding the main subject of a story or determining context clues, said Carrie Hahnel, deputy director for research, policy and practice at The Education Trust–West, a nonprofit advocacy group.

“We’ll focus on getting kids to the point where they can speak English before we teach them academic content,” Hahnel said.

Charter Schools

Independent charters and traditional public schools fared similarly statewide, though charter students performed better in L.A. Unified than traditional schools.

One reason that the district’s enrollment is decreasing is because families choose charter schools over neighborhood schools. L.A. Unified has more charter schools than any other district in the state, and that number continues to grow.

“Is it the strength of your academic program … or is it that the most motivated parents are choosing those schools?” said UCLA’s Noguera. “It’s hard to discern.”

The charter school students tested last school year were more heavily black and Latino than test-takers in L.A. Unified as a whole — and 81% were low-income versus 80% in the school system, according to analysis from the California Charter Schools Association and L.A. Unified.

As in other types of schools, there is a large range of scores among charters.

Within L.A. Unified boundaries, the schools with the highest scores in both math and English belong to the network of charters called Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP LA), which runs more than a dozen schools in South L.A and East L.A., according to its website. Kipp Raíces in East L.A. led charters in English, with 86% of elementary school students tested meeting standards, while 91% of students at Kipp Iluminar, also in East L.A., met math standards.

Charter schools bettered their scores from last year, as did the state’s schools as a whole, but improvement isn’t enough, California Charter Schools Association spokeswoman Emily Bertelli said in an email.

“It is important to keep in mind that this year’s statewide results also tell us that 50% or more of students are still not meeting standards, and we have a long way to go,” Bertelli wrote. “We need to have the more difficult conversations about schools that have yet to meet the needs of children.”

Reach Sonali Kohli at [email protected] or on Twitter @Sonali_Kohli.

MORE FROM EDUCATION

Finally, a disturbing trend in education shows signs of reversal

$1-million donation will help needy students with their homework at L.A. libraries

High schoolers can’t bank on their knowledge of money matters. These educators want to change that

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.