Small districts reap big profits by approving charter schools with little oversight

- Share via

The superintendent’s plan was born of necessity.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, as tax revenue plummeted, small school districts across California quickly felt the pain. Many were already lean, where administrators did the work of two or three, and students were counted in tens, not thousands. The economic collapse threatened their very existence.

In Superintendent Brent Woodard’s rural district, which covered the towns of Acton and Agua Dulce about 45 miles north of Los Angeles, enrollment in 2013 had fallen by more than a quarter over five years. The area’s population had aged, the birthrate declined and some students were choosing to attend schools outside the district. Without increasing revenue or making harmful cuts, the district was facing insolvency and the threat of a state takeover.

In California’s charter school law, Woodard saw financial salvation.

In the years to come, some would praise his creativity. Others would accuse him of embarrassing the district. Everyone agreed that his strategy was entrepreneurial, though not everyone meant it as a compliment.

Court records detail how — methodically and rapidly — the Acton-Agua Dulce Unified School District began approving new charter schools. The first year, there were two. The next: 11. By 2017, the district, which operates only three schools of its own, had authorized 17 charter schools.

How a couple worked charter school regulations to make millions »

Some were located outside the district’s geographical boundaries, in places like L.A., Santa Clarita and Pasadena. Some were based entirely online.

Each charter brought the district something it badly needed: money.

“It was common knowledge ... just go to [Acton-Agua Dulce], they’ll sponsor anyone,” said Ken Pfalzgraf, who won a seat on the district’s board in 2016.

Woodard did not respond to several requests for comment.

Across California, other small districts hatched similar plans as word spread that they could fix their financial problems by approving certain types of charters and then charging them for a range of services.

State law allows school districts to charge charters fees that are meant to cover the cost of monitoring the schools, but it does not restrict how districts use the money. As a result, districts have spent charter oversight fees on sports coaches, textbooks and computers for their own schools.

When the California Legislature passed the Charter Schools Act in 1992, it was intended to introduce competition into public education as well as an incentive for districts to experiment. There was supposed to be a marketplace of ideas about new ways of teaching and learning. But what has evolved in some parts of the state resembles an actual marketplace in which charter schools can shop for lenient authorizers and school districts can rake in much-needed cash.

Before he was elected to the school board for Acton-Agua Dulce, Pfalzgraf recalls attending meetings and watching with growing concern as a line of charter operators sought approval to open new schools. He remembers those meetings as breezy, friendly affairs in which the answer was nearly always yes and district officials asked few questions, even of schools known to have been rejected previously by other districts.

“You’re telling people they’re supposed to vet charters. But they also know that if there’s no charter revenue, they don’t have a job,” Pfalzgraf said. “I think staff was looking at this and going, ‘If I recommend no, what’s going to happen to me?’ ”

The district’s income from charter fees has more than doubled in the past five years, surpassing $3 million last school year. Roughly 25% of its operating budget now comes from those fees, according to its current superintendent.

Students attending the out-of-town charter schools have not always benefited. Last school year, most of the charters Acton-Agua Dulce oversaw posted lower passing rates on state exams than its own district schools. In four of the charters, more than 95% of students failed the math test.

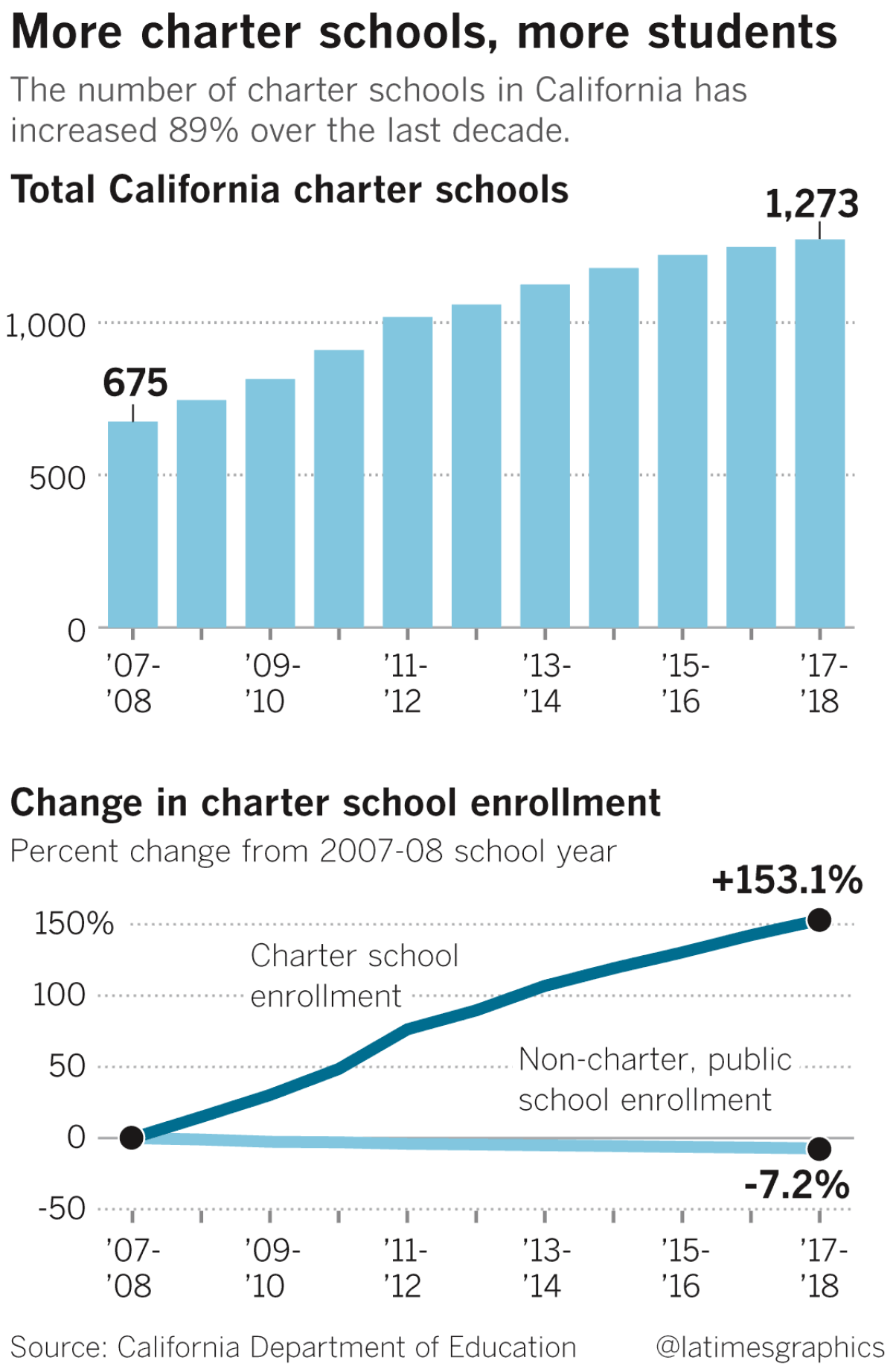

California has more than 1,000 school districts, and most do not rely on charter school fees to keep the lights on. In fact, charter supporters often complain, correctly, that districts have a strong financial incentive not to approve charters within their boundaries because the new schools may lure away students and the funding that goes with them.

But a Times analysis of enrollment data found more than 60 California school districts in which more than half of the students enrolled are attending charter schools.

Some run only a few neighborhood schools but have authorized as many as 10 charters. In Acton-Agua Dulce, about 1,000 children were enrolled in district-run schools last year; nearly 14,000, many of them from outside the area, were in district-authorized charters.

Many of the charters approved by small districts are classified as non-classroom-based, meaning their students receive much of their instruction off campus. Schools in that category typically aren’t a threat to district enrollment numbers because they draw from different markets — home-schooled children, students who work full time and others who have dropped out.

In Shasta County, for example, a one-school district with 35 students and one part-time administrator has approved three non-classroom-based charters.

In Kern County, a district with about 300 students has authorized five charters — all but one conducts most of its classes online.

In one small San Diego County district, charter oversight fees made up nearly a third of its operating budget last school year.

![Acton-Agua Dulce Unified School District board member Ken Pflazgraf said that when he joined the board, “It was common knowledge ... just go to [Acton-Agua Dulce], they’ll sponsor anyone” to establish a charter school.](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/e9e40a9/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2048x1278+0+0/resize/1200x749!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fd2%2F38%2F8cfab42ff99a03db3f6de132d51b%2Fla-1552432230-isplmrnlkk-snap-image)

‛Creative Financing’

School districts looking to make money from charters often begin by approving only charters that are unlikely to compete with their own district-run schools. Some take advantage of provisions in the law that allow certain charters to locate outside the boundaries of their authorizing districts — if, for instance, they can’t find a suitable school site in the district or partner with a job training program.

Under state law, districts that authorize charter schools can charge oversight fees of up to 3% of a charter’s revenue. In practice, however, districts can add thousands of dollars in fees or an array of extra services, such as help with human resources.

In the fall of 2017, the California state auditor released a report that exposed two school districts’ tactics of increasing revenue by approving out-of-district charter schools.

Investigators found that Acton-Agua Dulce had taken a 3.5% cut from each of its charters, surpassing the legal limit, even though its charters made only “sporadic use” of the extra services. The district ultimately reduced its fees.

The report also determined that New Jerusalem Elementary School District, located in a rural part of San Joaquin County, had overcharged one of its charters by $100,000, a finding the district disputed.

Charter operators are aware that the income they provide to districts can be vital, and they have courted small districts across the state.

“People were coming and saying, ‘Hey, we can give you somewhere between 1 to 3% of the enrollment [revenue],’ and the small districts were saying, ‘Boy, could we use that,’” said Justin Cunningham, a retired superintendent on the executive committee of the Small School Districts’ Assn.

Cunningham approves of what he calls this “collaborative model.” He was superintendent of the Bonsall Unified School District (population 2,930) in San Diego County, and he is familiar with the tight margins that make running a small district a challenge. If “the smalls,” as he called them, make deals with charter schools that financially benefit both sides, then it’s a win-win.

“It’s almost like what bankers call ‘creative financing,’ ” he said. “That’s how the schools are adapting to survive.”

A District Transformed

For the first century of its existence, the New Jerusalem Elementary School District consisted of a single schoolhouse surrounded by farmland. Located in Tracy, about 25 miles south of Stockton, the district had never had more than 240 students in kindergarten through eighth grade, according to its current superintendent, David Thoming.

In the mid-’90s, though, rising costs sent the district’s leaders searching for new revenue. When the charter law passed, they saw an opportunity.

Over the next two decades, New Jerusalem opened a series of what are called dependent charters — schools that are free from many state regulations but still controlled by their local school districts. The charters siphoned students away from neighboring school districts, along with the state revenue that came with them.

Thoming quickly got a reputation for being charter-friendly. When a lawyer representing charter schools called to ask if he would consider approving an independently run charter not controlled by the district, Thoming and his school board agreed.

After that, the tiny school district found itself awash in charter petitions.

By 2016, New Jerusalem was overseeing six independent charter schools in addition to its seven district-run charters and its lone traditional school. Over five years, its enrollment had soared from 686 students to 5,015, and millions of dollars had poured in.

“I’m not going to deny we were getting more money, but I do chafe when people say, ‘You guys were doing this just to bring in more money,’ ” Thoming said. “I felt like I was leading the charge for kids and for school choice. Looking back, I paid a price.”

Four of the independent charter schools New Jerusalem approved closed because of financial problems.

Two of them had begun to fall apart after only a year. Although the schools were authorized by New Jerusalem, they opened in Stockton Unified under the management of a nonprofit called the Tri-Valley Learning Corp. Loaded with debt and tainted by fiscal mismanagement, Tri-Valley in 2016 declared bankruptcy and closed all of its charters the following year.

Under California law, there are no penalties for school districts that authorize and don’t adequately supervise charters that are poor-performing or financially troubled. No one can revoke a district’s authority to approve more charters or require it to improve its oversight.

About the only thing the state can do is call for an audit. The state auditor chastised New Jerusalem for not doing enough to police the Tri-Valley charters.

Thoming said the audit’s criticism was overstated. By his account, once he saw the problems, he went after the charter group, ultimately spending about $500,000 in legal fees to shut them down. What he got for his effort, he said, was unfair criticism.

Still, Thoming said he became concerned that charter operators were choosing New Jerusalem because they saw its leaders as easy marks.

In March 2017, he received a vaguely worded charter petition that seemed to confirm his fears.

The paperwork for the virtual charter school, to be called Rise Academy, looked as though it had been inexpertly copied from another charter school’s proposal. Page numbers were cut off, one document was for a school called California Prep, and all of the parents who had signed a petition in support of the school had home addresses in another part of the state. When Thoming called them, several told him they had no interest in Rise Academy.

(The Times also made calls to the parents on this list. Most did not answer, but two who did said they had never heard of the charter.)

Thoming said Rise Academy’s petitioners offered him a deal sweetener. If the school was approved, they said, on top of oversight fees, they would reimburse the district for any money it would lose if its students switched to the charter.

“Their main pitch was, ‘You’re going to get more money,’” Thoming said. “I remember thinking: That’s dirty. That completely flies in the face of the charter law, which is to provide competition.”

Rise Academy’s leaders eventually withdrew their petition. They would try again, petitioner Greg Ruffin wrote Thoming, with “another district that is comfortable with charters.”

In an interview, Ruffin said that although he was one of the charter’s founders, he had no role in writing the petition or collecting signatures and that he didn’t know who was responsible. He said he had mistakenly submitted the wrong list of parent signatures but the district wouldn’t let him fix the problem. Of New Jerusalem, he said: “They were very hostile.”

The Times contacted three other people involved in Rise Academy’s petition, but none responded to requests for comment.

The thought of Rise Academy approaching other school districts, shopping for one that wouldn’t examine its petition too closely, made Thoming uneasy. He understood small districts’ financial pressures. He knew some superintendents didn’t have the time or the know-how to tell a well-meaning charter operator from a profiteer. He acknowledged ruefully that he had been one of them.

What he didn’t know was that the same group behind Rise Academy had sent nearly identical applications to a handful of other small districts that had approved them. It was already in business under different names.

No Strings Attached

California doesn’t track whether the fees charter schools pay school districts are used to monitor charters or hire football coaches.

Districts that properly exercise their oversight powers often find that the fees don’t come close to covering their costs. The $10.8 million that L.A. Unified collected last year, for example, fell short, according to district officials, of the expense of overseeing its more than 250 charters.

But for districts that do the bare minimum, charter fees become new revenue.

Across the state, charter oversight fees have subsidized sports programs and extracurricular activities as well as the salaries of teaching assistants and classroom aides.

There have also been cases of less altruistic spending.

In 2016, former Mountain Empire Unified School District Supt. Steve Van Zant pleaded guilty to violating conflict-of-interest laws. Van Zant, prosecutors said, had been getting a cut of the fees from each charter school the district authorized, and some of those charters had hired his consulting firm. In his plea deal, he agreed to reimburse the district for roughly $51,000.

Recently, a rural county in the Eastern Sierra has been embroiled in a dispute over how its superintendent spent fees from the three far-flung charter schools it authorized.

Mono County Supt. Stacey Adler told the Orange County Register that some of the money had gone to spelling bees, mock trials and other programs that the state did not fund. But a former employee alleged in a lawsuit that Adler had paid herself from the fees.

Adler declined to comment. In a statement to the The Times, Mono County Office of Education attorney Timothy Cary said that the school board had not found that she “did anything inappropriate” but that she would pay back all of the $24,500 by June “to avoid any negative public perception.”

An Old Problem

The fact that some authorizers have a financial incentive to approve online and out-of-district charter schools and keep them open regardless of performance has not been lost on the charter movement’s leaders.

Each year since 2011, the California Charter Schools Assn. has published a list of “chronically underperforming” charters that it believes should be closed — based primarily on test scores and graduation rates. In assembling the list, the group has encountered districts that have refused to shut down charters even after they’ve been given evidence that the schools are failing students.

But charter advocates and teachers unions have been unable to agree on legislation to solve the problems. The political gridlock has left districts and counties to decide for themselves what kind of authorizers they want to be.

In Acton-Agua Dulce, the district now is eager to break with its past.

“You have to ask yourself, why are these charters really picking us as their authorizer?” said board member Pfalzgraf. “I don’t like having the reputation of a barfly. I’m not easy,” he said.

Woodard, the superintendent who made approving charters a side business, left the district in 2017. Lawrence King, the veteran administrator who replaced him, said the district thoroughly reviews charter applications now. “We take our oversight responsibilities very seriously,” King said.

He has said he would like to improve the district’s reputation, returning it to a time when it was better known for its own schools than for its lucrative fleet of charters.

But that’s easier said than done.

Though financial problems have caused several of its charters to shut down in the last year, Acton-Agua Dulce still oversees 15. It remains heavily dependent on that income.

Twitter: @annamphillips

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.