Can Inglewood’s NFL-fueled turnaround be a success if its schools are failing?

- Share via

Laura Rosales, mother of three, lives blocks from the site of Inglewood’s planned NFL stadium.

Watching the fast-moving construction of a futuristic complex that is expected to bring thousands of jobs and millions of dollars in tax revenues to the city makes her think about the toilets at her 7-year-old son’s school.

They are so dirty that he waits until he gets home to use the restroom. The high school that her teenage daughters attend chronically underperforms academically, as do most of the district’s schools.

And those aren’t the only problems. Three years ago, after Inglewood school administrators hugely and repeatedly overspent their budget, the state took control of the district.

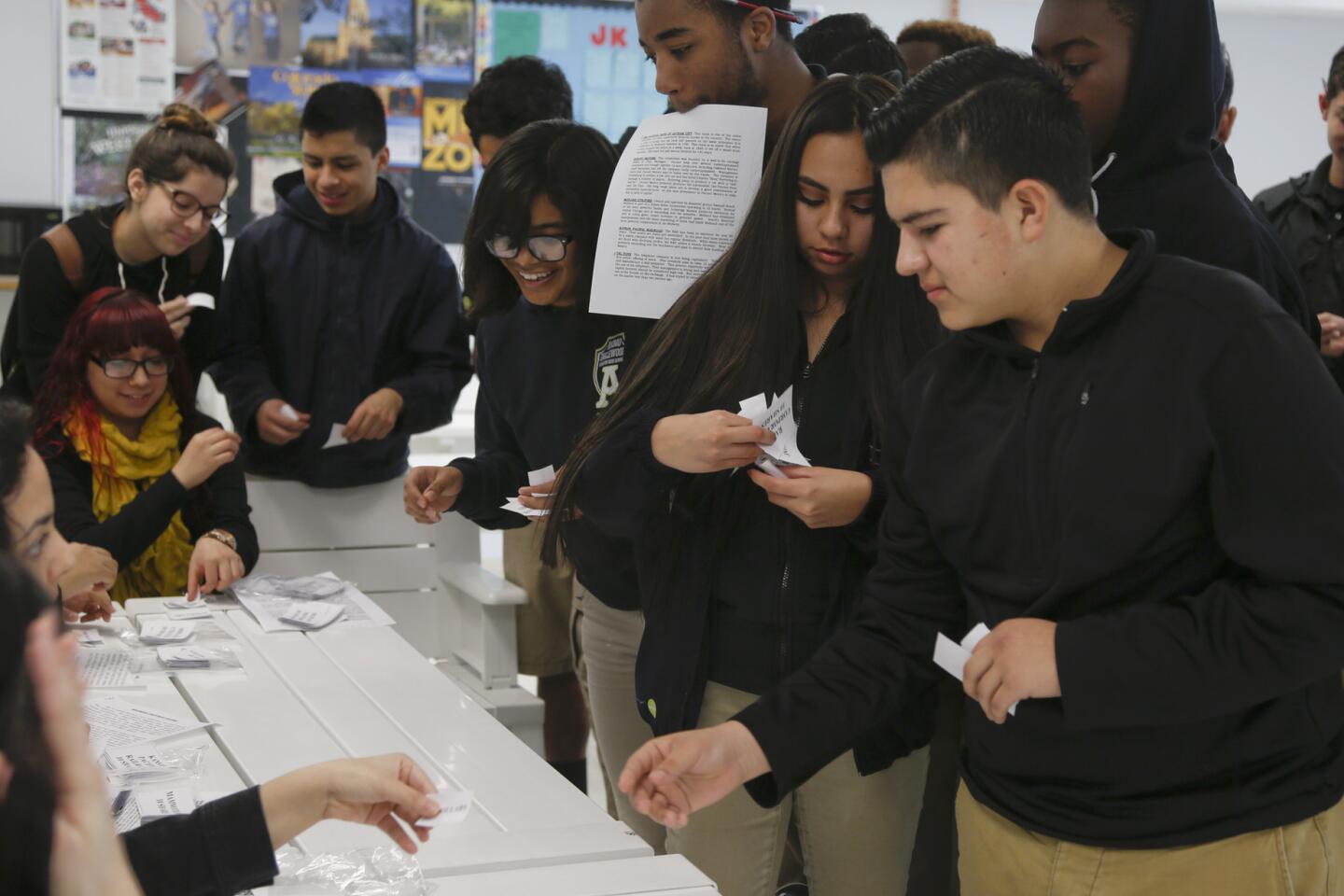

By then, thousands of children had already flocked to a growing number of charter schools taking root in the area, and the exodus has continued. Today about 20% of Inglewood students attend one of nine independent charter schools within the district’s boundaries.

Charter advocates say these schools give parents like Rosales a path to a better education for their children. But even with these independent schools, Inglewood students still are lagging far behind.

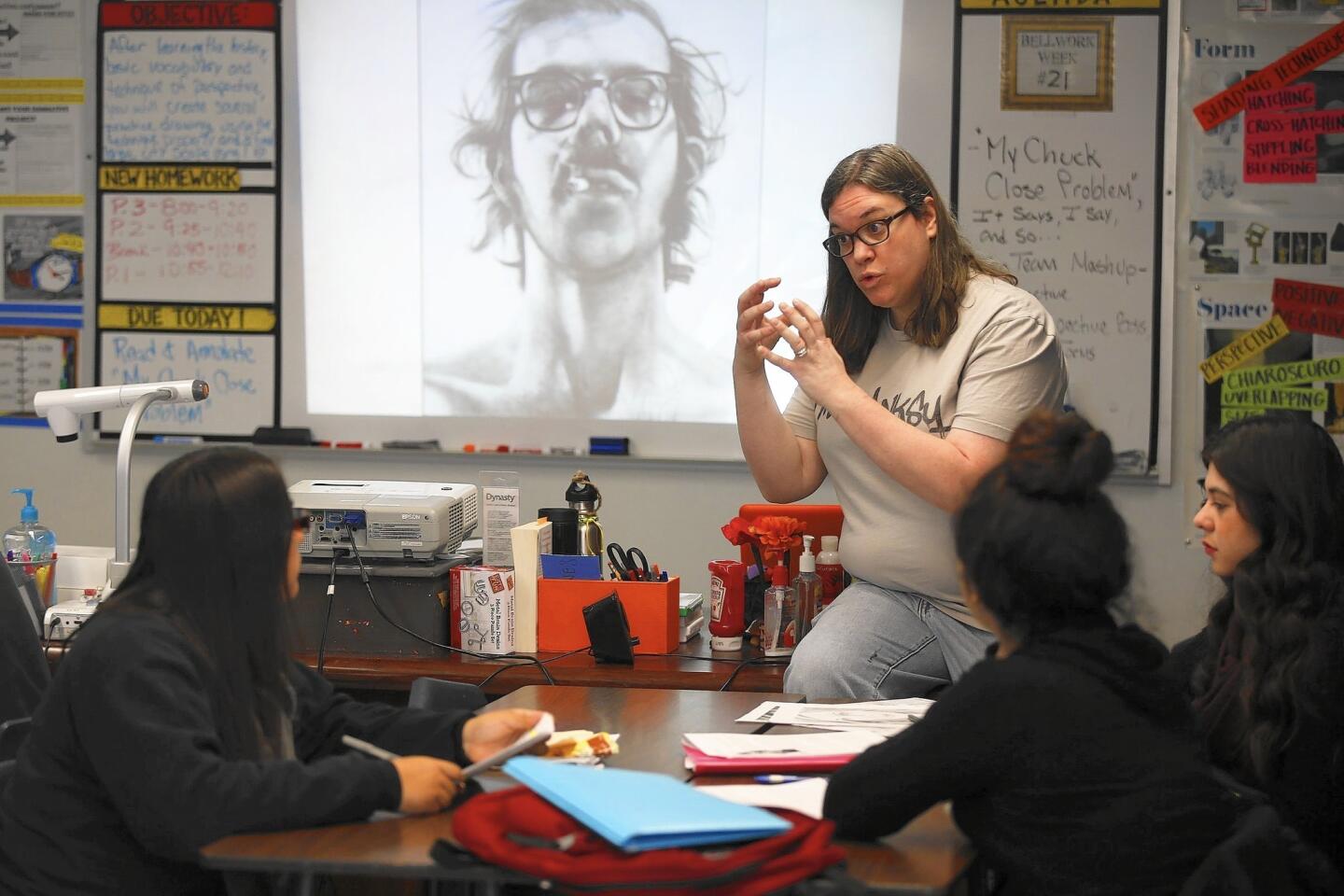

As a whole, Inglewood charter schools outperformed district schools on new, more difficult state exams. But an analysis by The Times shows that although the city has a few high-achieving charters, most of the charters, like most schools in the district, still performed below the county average.

Some educators believe certain charters do better in part because they draw the most motivated students whose parents have given up on the traditional schools.

Understanding how well charters operate relative to traditional public schools is important not just to students in those schools but also to the overall discussion of public education, in part because charters lure students — and the taxpayer money that goes with them — from traditional campuses.

Across Los Angeles County, about 41% of students passed state exams in English and 30% passed their math exams.

No schools in the Inglewood district met the county average in math and only one did in English. That school, Highland Elementary, tested 21% English learners and 7% students with disabilities — constituencies that experts say need to be taken into account as they tend to lower overall scores.

In comparison, an analysis by The Times shows that three of the nine charter schools in Inglewood exceeded county passing rates.

One of those schools, Animo Inglewood Charter High School, is among the highest-performing campuses across the state — 87% of students at Animo passed English and 73% met math standards. About 15% of students who took the test are learning English and 7% have disabilities.

The other two schools that exceeded county pass rates had fewer than 10 students taking the test who had disabilities or were learning English. A vast majority of students at the two schools are black.

Although Animo brought up the overall test scores for charters, the full picture of education in Inglewood remains bleak. Among the worst examples, only 1%, of students at Morningside High, a traditional public school, and at Children of Promise Preparatory Academy, an elementary charter school, met state standards for math.

In January, Vincent Matthews, the latest state-appointed administrator to lead the district in its quest to regain independent status, issued a long-awaited draft plan of what the district needs to do to wrest itself from state control. It calls for various changes, including the creation of stronger academic programs to lure 4% of charter students back to the district by 2018-19 and an additional 4% each following year.

Declining enrollment — including the exodus to charters — has left the district with fewer than 11,000 students and less money for improving facilities, maintaining academic programs and retaining staff.

“It’s just this revolving circle that keeps gnawing away at itself,” Matthews said.

UCLA education professor John Rogers agrees that the underlying financial and academic failures at the district were compounded by the growth of charter schools. And, he said, the same challenges could face the vastly larger Los Angeles Unified School District, if charters succeed in enrolling up to half of the district’s students over the next eight years, as outlined in a charter expansion proposal drafted by the Broad Foundation.

That plan, Rogers said, “presumes that competition and the market is a way to lift all boats in effect and what we see in Inglewood and what I fear for the future of Los Angeles is that competition leaves a lot of boats that are sunk in its wake. Particularly over the short term, it’s very difficult for districts that are already struggling to survive that level of instability.”

Charter supporters argue that districts often overstate the threat to traditional public schools.

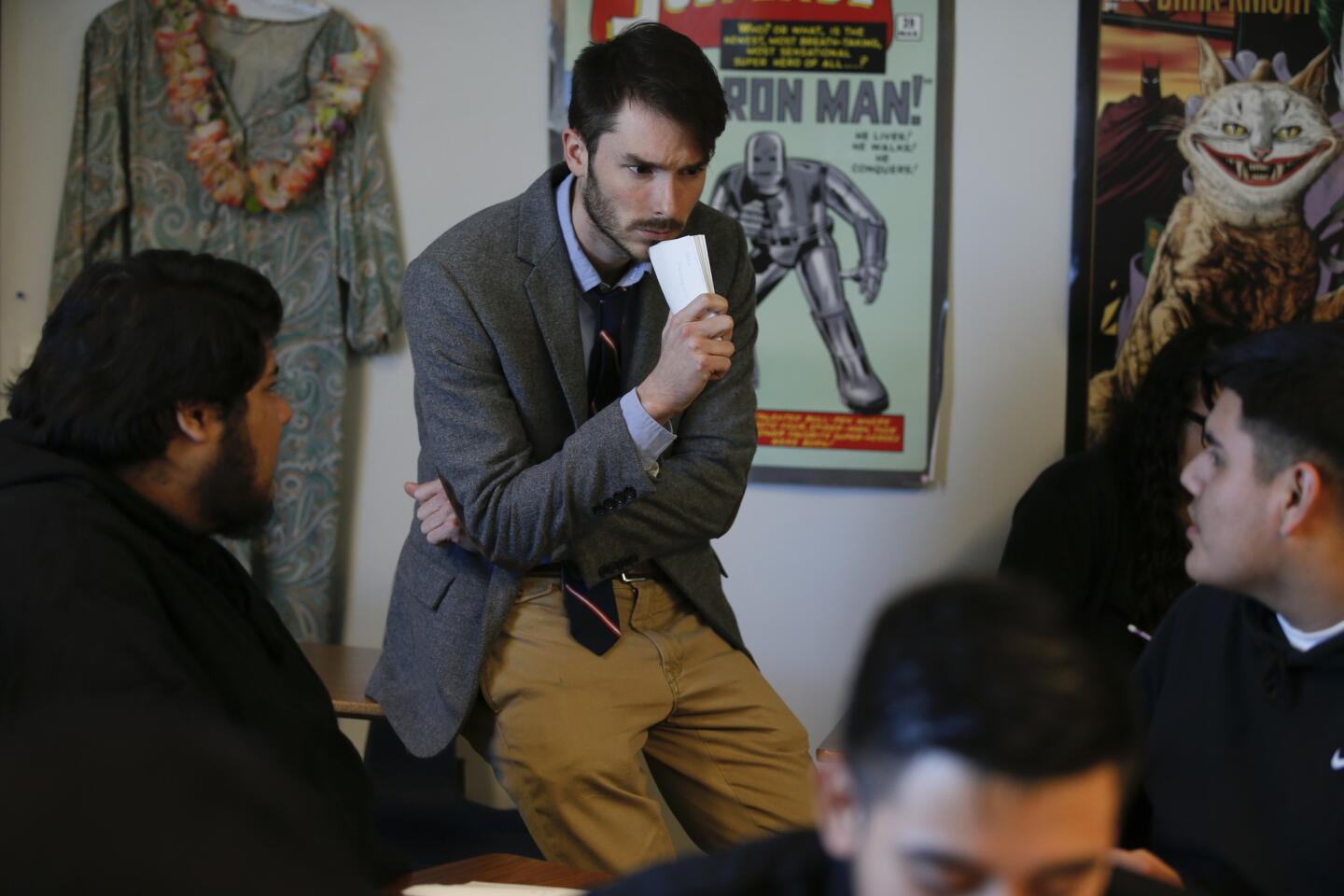

“Do I have sympathy for them? No,” said charter activist Steve Barr, who founded Animo.

He said school districts should learn from successful charters instead of blaming them.

“That’s what happens in competition. That’s what happens when organizations don’t adjust to pretty obvious trends. They’re either going to get it or they’re not,” Barr said.

The California Charter Schools Assn. says it may call for the closure of Inglewood charters that consistently underperform, but it argues that other charter schools should not be deemed bad simply because they do not meet county averages.

Matthews, the state administrator, said he is beginning to delve deeper into charter performance. He said the district should support successful charters but schools that are not up to par should be held accountable.

He and other education experts note that restoring parents’ and students’ faith in the district is also key.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

One way Inglewood might staunch the flow of students, said state superintendent Tom Torlakson, is to develop innovative district-run charter and magnet schools, such as a pre-engineering and construction academy that would somehow tap the expertise and economics pouring into the new football stadium.

The lack of a strong public education system frustrates Inglewood leaders, who say they know that the draw of professional football will not be enough to bill the city as a turnaround success if its schools are failing.

“While people are proud of the progress the city has made, we definitely need to see that replicated in the school district,” said Mayor James Butts.

In the meantime, Rosales, the mother of three, worries that neither the charters nor the district will improve fast enough to significantly improve the education of her son, a first-grader, let alone her daughters, a junior and a senior in high school.

“It’s just a string of disappointments,” she said.

Twitter: @zahiratorres

Times staff writer Sandra Poindexter contributed to this report.

Editor’s Note: The Times receives funding for its Education Matters digital initiative from one or more of the groups mentioned in this article. The California Community Foundation and United Way of Greater Los Angeles administer grants from the Baxter Family Foundation, the Broad Foundation, the California Endowment and the Wasserman Foundation to support this effort. Under terms of the grants, The Times retains complete control over editorial content.

MORE FROM EDUCATION

Magnet schools: How to navigate one of L.A.’s most complex mazes

The UCLA gymnast who became a viral sensation by just being herself

College freshmen are more liberal and keen on political activism, survey says

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.