L.A.’s share of river restoration could hit $1.2 billion

- Share via

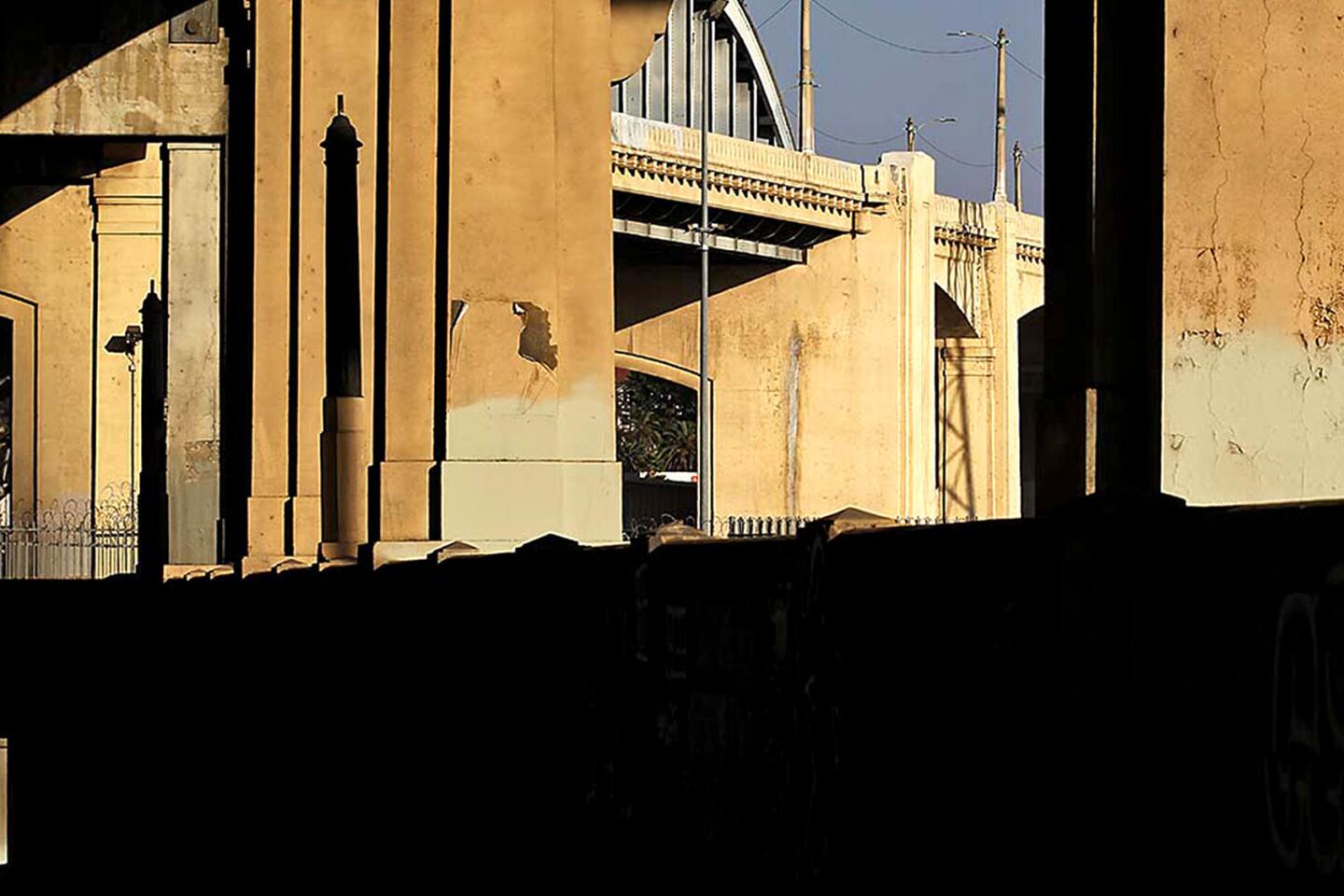

Returning the Los Angeles River to a more natural state has long been a dream of city officials, who see it as a way of adding parkland, restoring habitat and attracting investment along its curving path from Griffith Park to downtown.

That effort seemed to get a big boost last year when Mayor Eric Garcetti announced support from a high-level federal official for an ambitious plan to remake the river. City leaders had been hoping to split the expense evenly with the federal government by contributing about $500 million over the life of the project.

But now, a new report says the city’s share of the cost could rise to as much as $1.2 billion.

The growing cost projections have city budget analysts warning about difficult work ahead in identifying the funds for the river restoration, which is expected to take 30 to 50 years.

“We are going to have a heavy lift,” Assistant City Administrative Officer Patricia J. Huber told lawmakers earlier this week.

Estimates for the overall project cost have also been increasing. The largest took place after federal officials refined the estimate for acquiring and relocating a major rail yard not far from the Twin Towers jail downtown. That added more than $200 million to the total, city officials said.

Chief Legislative Analyst Sharon Tso, who issued the report, cautioned that the numbers are “constantly evolving.” The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which would oversee the restoration, is still preparing its final report on the project. Still, even the alternative plan under discussion, one seen as more favorable to the city, would leave Los Angeles on the hook for $965 million, or 71% of the project’s overall cost.

Garcetti spokeswoman Vicki Curry acknowledged that the project’s price tag is being revised upward. But she said there will still be plenty of time for the mayor to seek a more favorable financial arrangement from the federal government.

Federal officials are scheduled to submit a report on the river project this summer to Lt. Gen. Thomas Bostick, commanding general of the Corps of Engineers. He, in turn, is expected to decide by the end of the year whether to recommend the project to federal lawmakers.

“There are many opportunities for the city to negotiate the cost share as the river restoration project moves forward, especially when the project goes to Congress for appropriation,” Curry said.

The City Council voted Wednesday, without comment, to send the federal government a document stating that it is financially capable of pursuing the project. As part of that decision, budget officials prepared a menu of possible funding sources for the restoration, including anti-pollution grants, state water bond revenue, soil cleanup funds and even a local tax increase.

The budget deliberations come at a time of heightened anticipation for the project, which is expected to introduce the most dramatic changes to the river since it was lined with concrete as part of a larger flood control initiative in the middle of the 20th century.

Once finished, supporters say, the restoration would result in the removal of concrete from sections of riverbed near Cypress Park, Chinatown, Glendale and elsewhere. Wetlands would be reintroduced near downtown; tributaries would be re-created from storm drains.

Those changes, Curry said, would add long stretches of open space while creating 9,000 construction jobs.

“Freeing the river from its concrete straitjacket and restoring it to its natural beauty will transform Los Angeles,” she said in an email. “It will create miles of open space within our dense urban area and bring new life to the neighborhoods around it.”

Some contend that the restoration plan has triggered a land rush along the river. Since the plan was announced, neighborhoods such as Elysian Valley have seen “enormous speculation,” said Kevin Mulcahy, an architect who works in that community.

Sale prices for riverfront property in Elysian Valley, between the river and the 5 Freeway, have doubled in the last 24 months, Mulcahy said. To justify those high prices, real estate developers are now proposing four- and five-story residential projects along the river — a change that has been greeted with alarm by some, he said.

“There’s going to be an urban wall” of residential buildings along the river, Mulcahy said. “It’s going to feel more like an urban canyon, rather than the softer, more landscaped vision [of the river] that we’ve been rallying behind.”

Federal officials initially recommended a smaller, 598-acre river restoration initiative last year. After Garcetti intervened, Assistant Secretary of the Army Jo-Ellen Darcy recommended the more extensive proposal to the Corps of Engineers.

At that time, Curry said, federal officials favored an approximate 50-50 cost share for the river project, albeit with certain conditions. One of those conditions is a limit on the amount of federal money that can be provided to the city to cover land acquisition. That, in turn, has caused the city’s overall obligation to go up.

“Real estate in L.A. is extremely expensive, and a project done in a highly urbanized area makes this more expensive than any other restoration project in the country,” said Jay Field, spokesman for the Los Angeles office of the Corps of Engineers.

Councilman Mitch O’Farrell, whose parks committee has been reviewing the project, has held multiple sessions on potential sources of outside funding. O’Farrell, whose district includes a stretch of the river, said he hopes that negotiations between the city and the federal government will produce a cost-sharing formula closer to 50-50.

Although he voiced strong support for the river project, O’Farrell said he also does not want to place new financial pressures on city finances.

“We want the best product” for the 11-mile stretch of riverfront, O’Farrell said. “We want it to be within reason, within reasonable cost, not at the expense of everything else we do in the city.” One possibility presented to the panel is a $1-billion citywide bond measure — a property tax increase that would require two-thirds voter approval. Budget officials prepared a document saying that half the bond’s proceeds could be tapped for the river.

Lewis MacAdams, president and founder of the nonprofit Friends of the Los Angeles River, said previous estimates for the project’s cost were only preliminary. He did not voice alarm at the changing numbers, saying that the project was always contemplated as one that would take decades to complete.

“The only way it’s going to be paid for, as far as I can see, is over a long period of time,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.