Once home to the Lakers and L.A.’s first Democratic Convention, this arena is getting torn down with little fanfare

- Share via

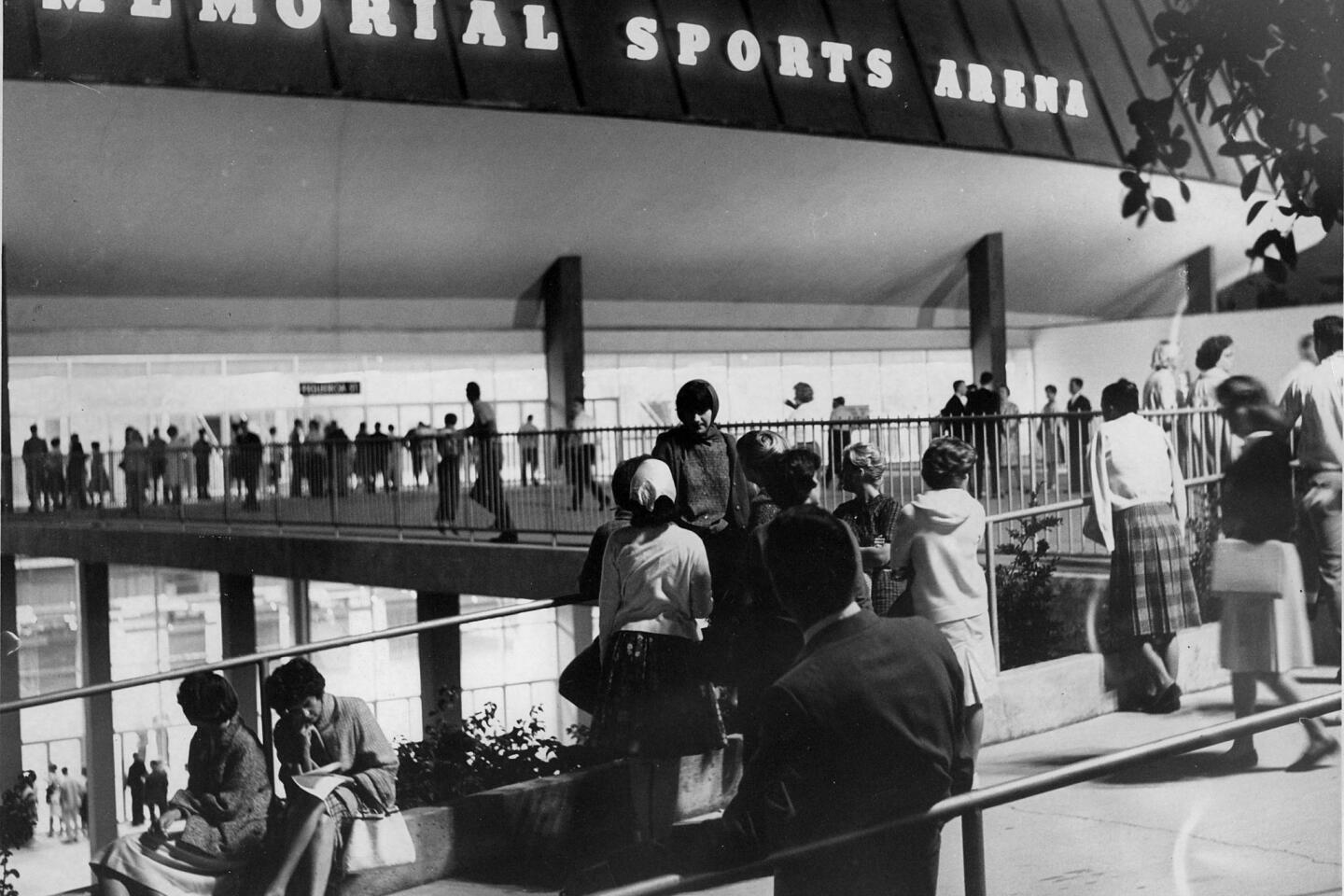

Few will mourn it. Many had never seen it up close. Some didn’t even know of its existence.

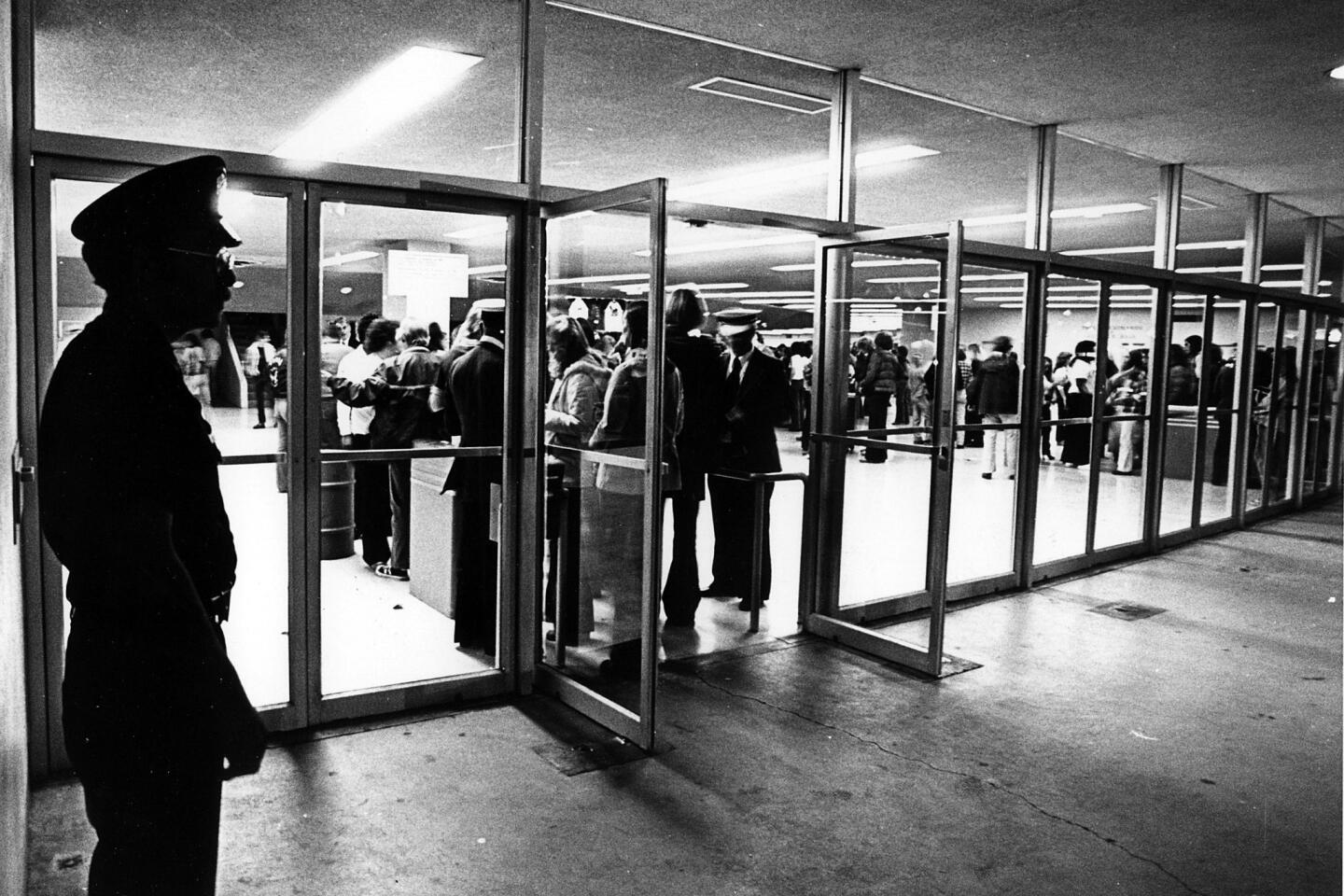

And so the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena — now a mass of dusty concrete and steel — is slowly being razed with little public outcry.

It’s a finale that characterizes the city’s apathy for a 57-year-old has-been that plodded through the decades in the shadow of glitzier venues.

Soon to rise in its place is a 22,000-seat stadium that will host a Major League Soccer franchise.

In its later years, the arena became an object of disdain, faulted for its dated decor, spartan concession stands and patched-up seats.

“Sports Arena brings out the worst in a crowd,” declared a 1999 headline about the venue, set in Exposition Park south of downtown.

Although it had been the first home of the Los Angeles Lakers, shelter to the Clippers for 15 years, and the dutiful servant of UCLA and USC basketball teams, the Sports Arena suffered from a muddled identity, never tugging at nostalgic heartstrings in the way that landmarks should.

And yet it once held the pulse and promise of Los Angeles inside its elliptical frame.

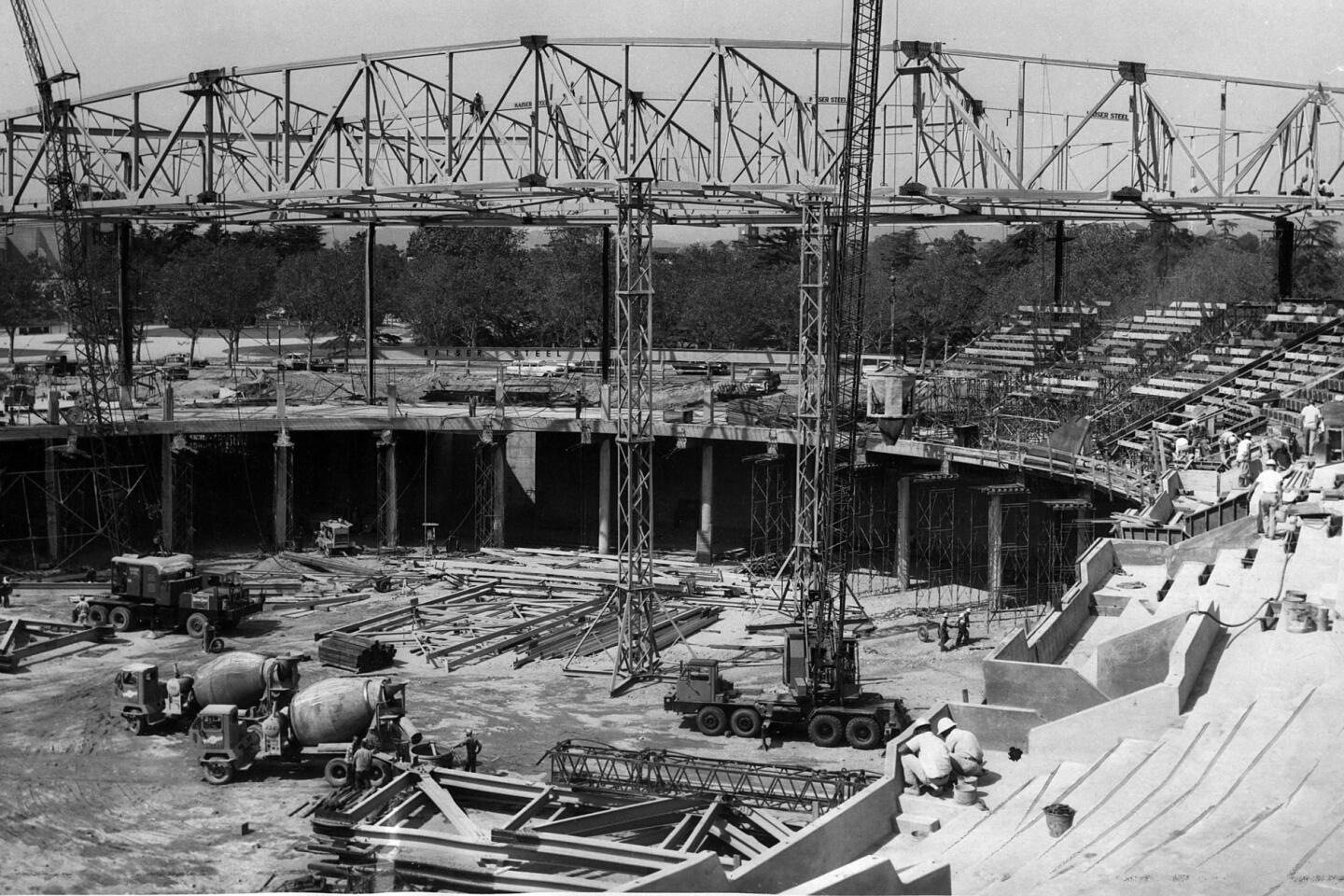

When it opened July 4, 1959, the shiny $6-million venue was lauded as the future of the city, a more versatile host than its vastly bigger next-door sister, the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

“The city had so little in those days in the way of facilities,” recalled Martin Brower, 88, who worked as a publicist for the arena’s architectural firm, Welton Becket & Associates. “The arena represented an era of something great happening in Los Angeles.”

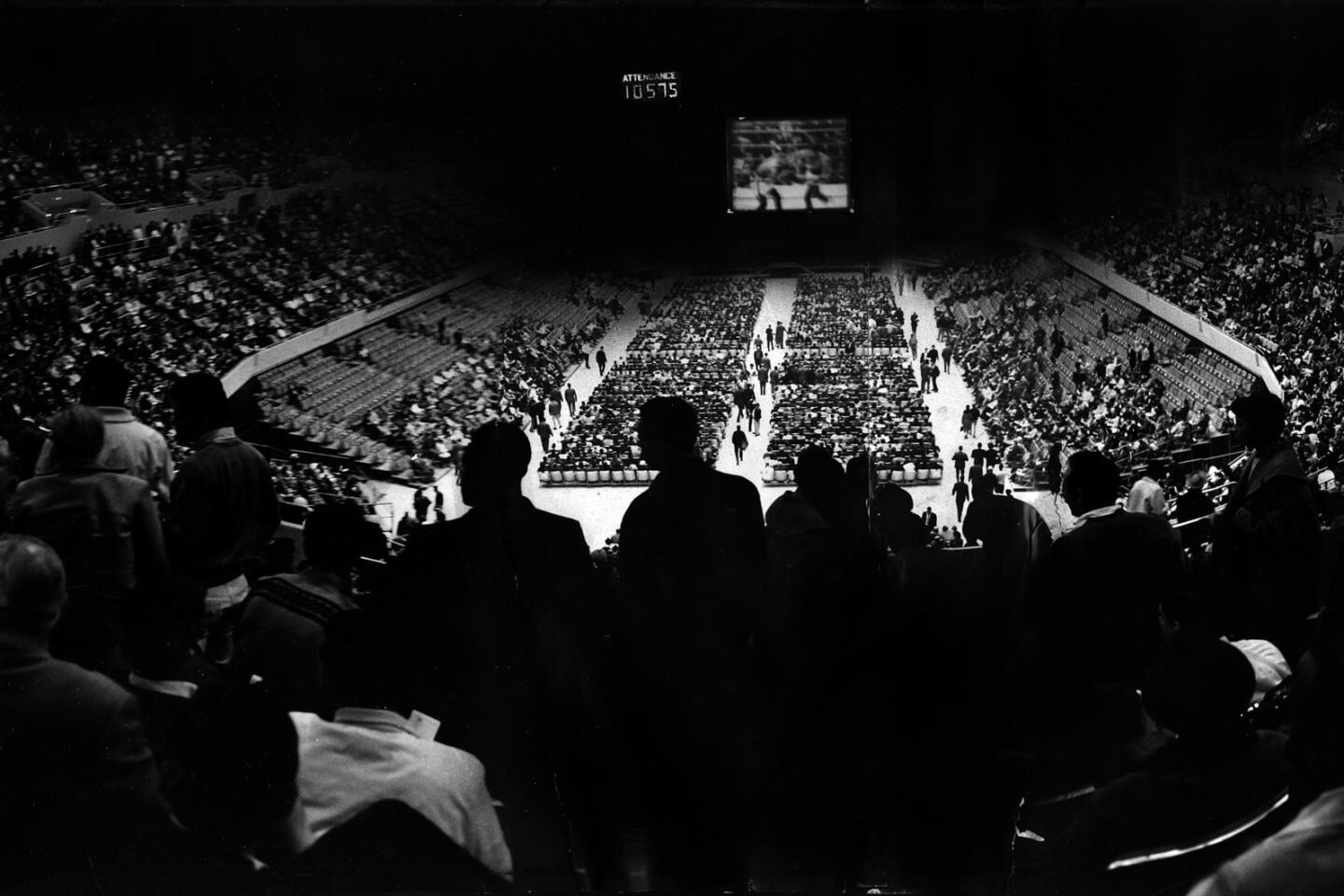

Built to host “spectacular” athletic events, trade shows, conventions and circuses, the arena soon swelled with boxing, wrestling and tennis matches, as well as rodeos, ice-skating performances and home exhibitions.

At the time, USC and UCLA were playing on a stage at the Shrine Auditorium and at the Pan Pacific Auditorium. Suddenly the two teams had a respectable and expansive home court.

The Lakers soon arrived. So did the Democratic National Convention in 1960.

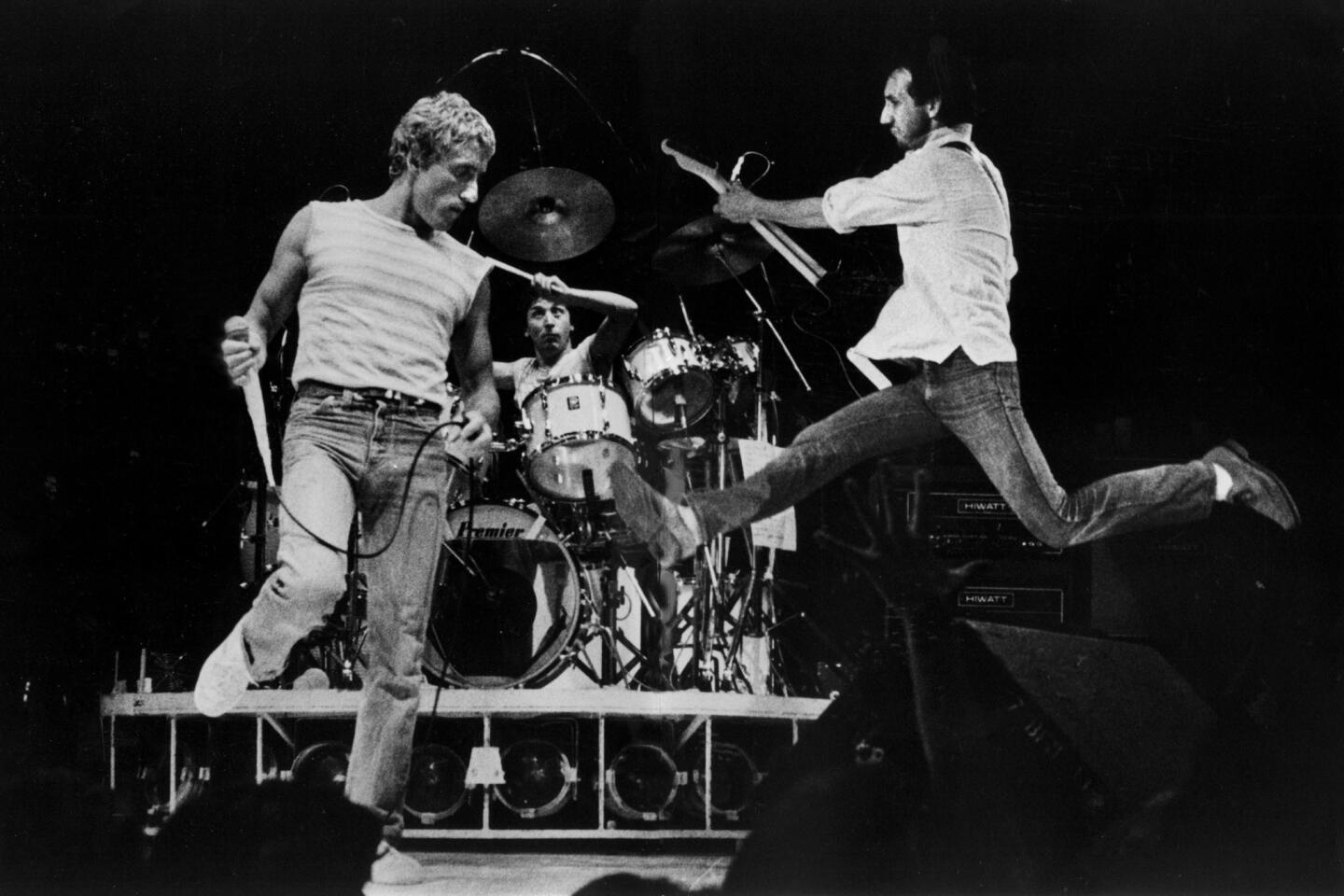

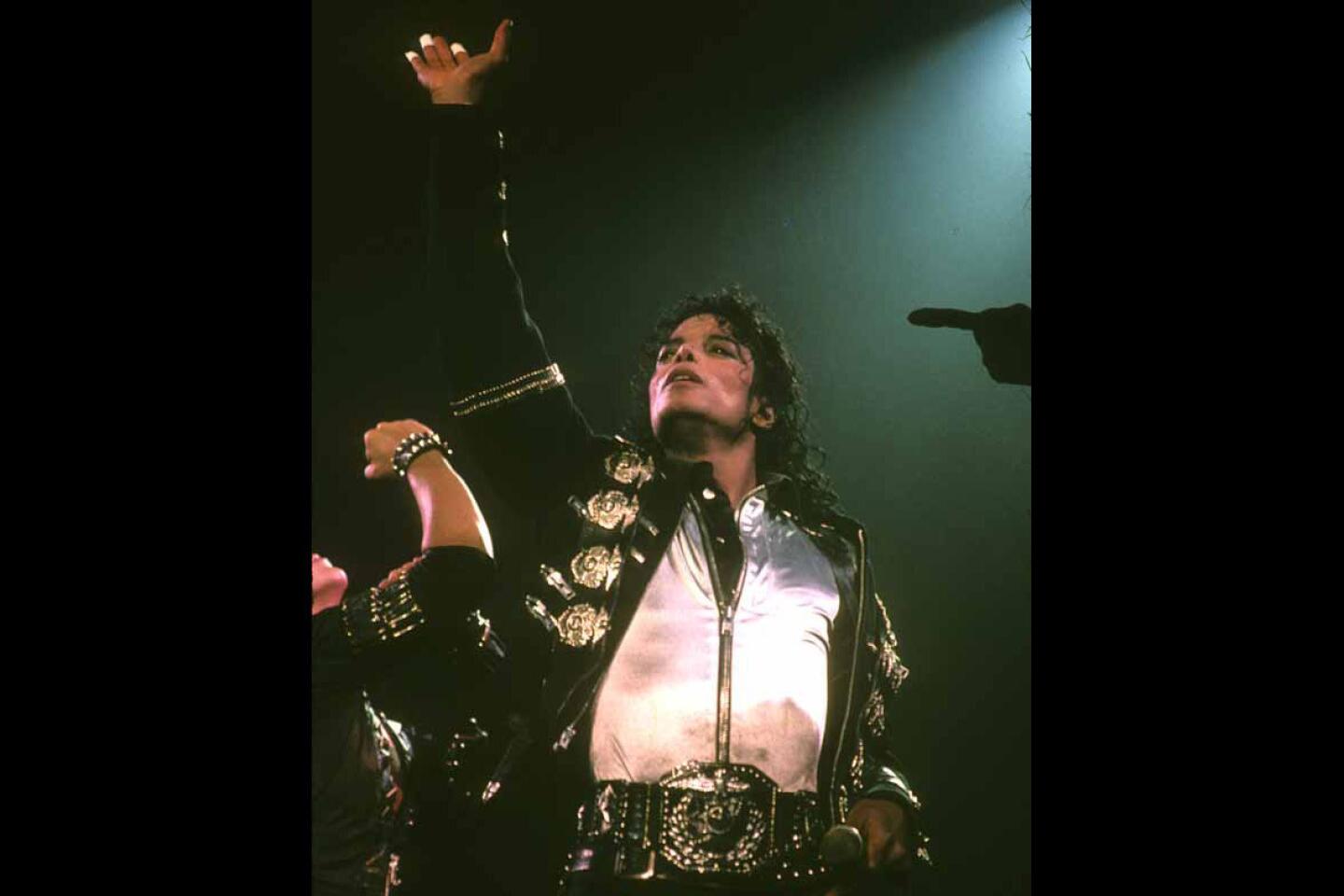

The arena is where Cassius Clay — before he assumed the name Muhammad Ali — made good on his prediction that he’d knock out Archie Moore in the fourth round, where Jim Beatty shattered the four-minute indoor mile, where Michael Jackson closed out his first solo concert tour, “Bad.”

“You could change the operation from a prize fight to a circus to a concert in short order,” recalled Jim Hardy, 93, who managed the Sports Arena as well as the Coliseum from 1973 to 1986. “And when the events were attractive to a group, they’d pack the joint.”

Still, there may have been signs of the Sports Arena’s destiny as a second-class citizen even during its early days.

Basketball legend Gail Goodrich, who played there as a Bruin and a Laker, recalled a sparse locker room that quickly became outdated.

“It was more like a dressing room for Broadway or an entertainer,” said Goodrich, 73. “It was hard to get 15 guys in there and it felt like a makeup room — it had a mirror on one side and a counter and then you had stools. There were no actual lockers for each player.”

When the mayor invited President Eisenhower to officiate at the arena’s grand opening, they instead got Vice President Richard Nixon.

It had that old-school vibe and that’s what I loved about it.

— Danny Hizami, owner of Figueroa Philly Cheese Steak

Later, the arena hosted the city’s first Democratic National Convention, but nominee John F. Kennedy opted to give his acceptance speech at the adjacent Coliseum.

Even the 1959 inaugural college basketball game between UCLA and USC was considered a disappointment because of what would become a recurring critique: low turnout.

“Thousands of fans will show up at the Sports Arena for a Clipper game disguised as empty seats,” a sportswriter mocked three decades later.

Players and coaches often blamed the setting.

“It’s just sort of a gloomy building, it’s so old and everything about it seems to be dull,” Laker Jon Barry once said.

It didn’t help that a series of unmemorable sports franchises landed at the arena, only to fizzle out. And then there was the matter of Jack Kent Cooke, then the owner of the Lakers.

Cooke had a delicate relationship with the Coliseum Commission ever since his initial request of a 10-year lease for the Lakers was countered with a two-year agreement. He had also balked at the arena’s demand he pay $50,000 annually into a “talent-procurement fund” to be administered by the commission. In 1965, Cooke put in a bid for an NHL expansion team, sweetening his offer with the promise of a brand-new arena. A year later, Cooke broke ground on the Forum in Inglewood, eventually taking the Lakers with him, as well as his newly acquired team, the Kings.

By then, the Bruins were long gone, enjoying their brand-new Pauley Pavilion. In 1999, a gleaming Staples Center opened, boasting both the Clippers and the Lakers. Seven years later, the Trojans were playing in their own Galen Center. Trade shows and performances made their way to the Convention Center and the imposing Music Center.

Times were changing. The Sports Arena did not.

By 2012, the arena and the Coliseum were struggling financially, having lost more than $7 million because of mismanagement. Corruption charges were filed against three former managers of the property, which also came under fire for hosting raves at which attendees overdosed on Ecstasy.

Later, the Coliseum would make plans for an estimated $270-million renovation, while the arena was drawing events such as an annual health clinic, a drone expo and a K-pop fest.

Developer plans Pershing Square condo tower with balcony lap pools »

In 2014, Mayor Eric Garcetti suggested razing the arena to welcome George Lucas’ “Star Wars” museum.

Although it had undergone a seismic retrofit in 2001, the arena never received a major overhaul to give it the modernity patrons had come to expect at Los Angeles events.

For some, that was its charm.

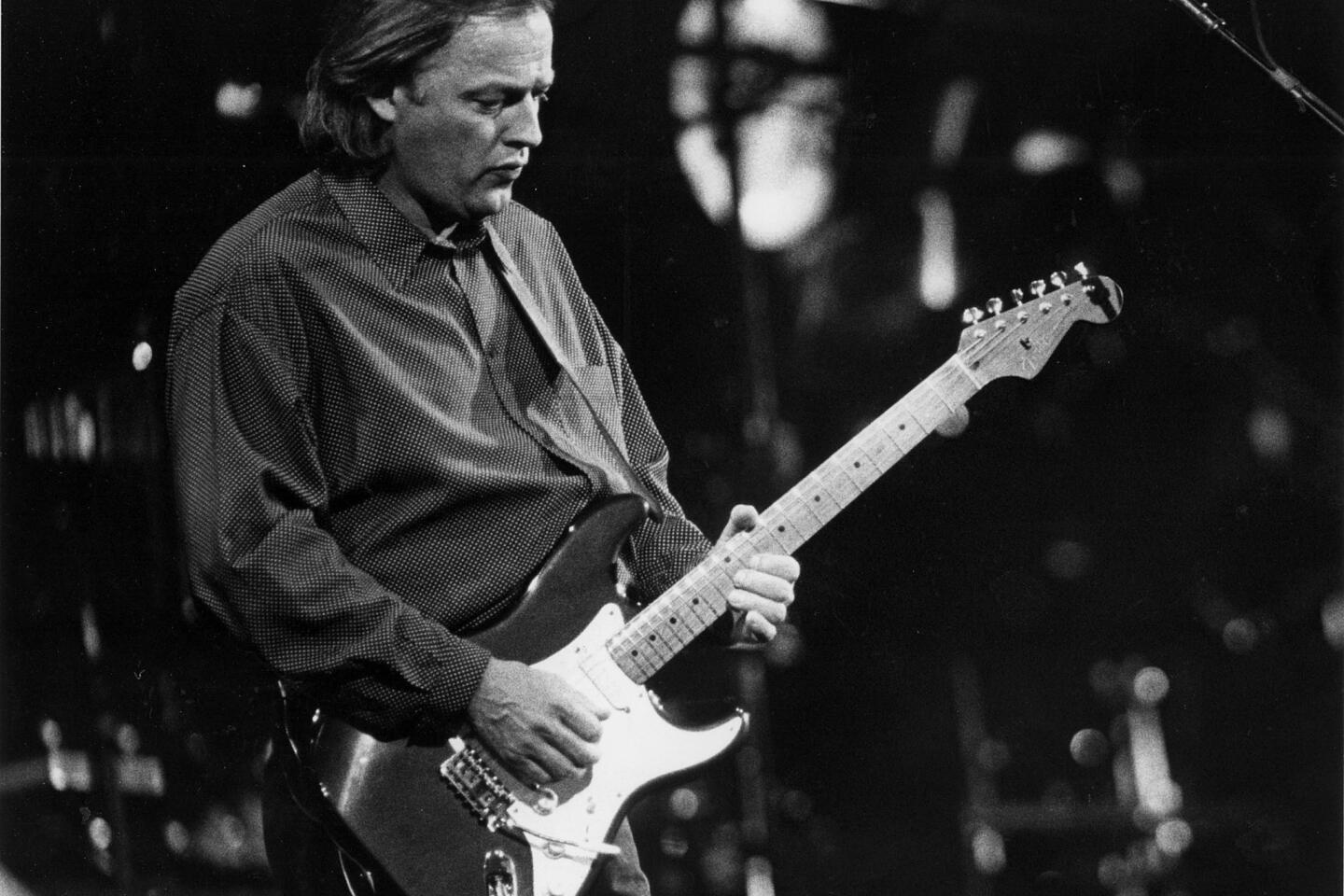

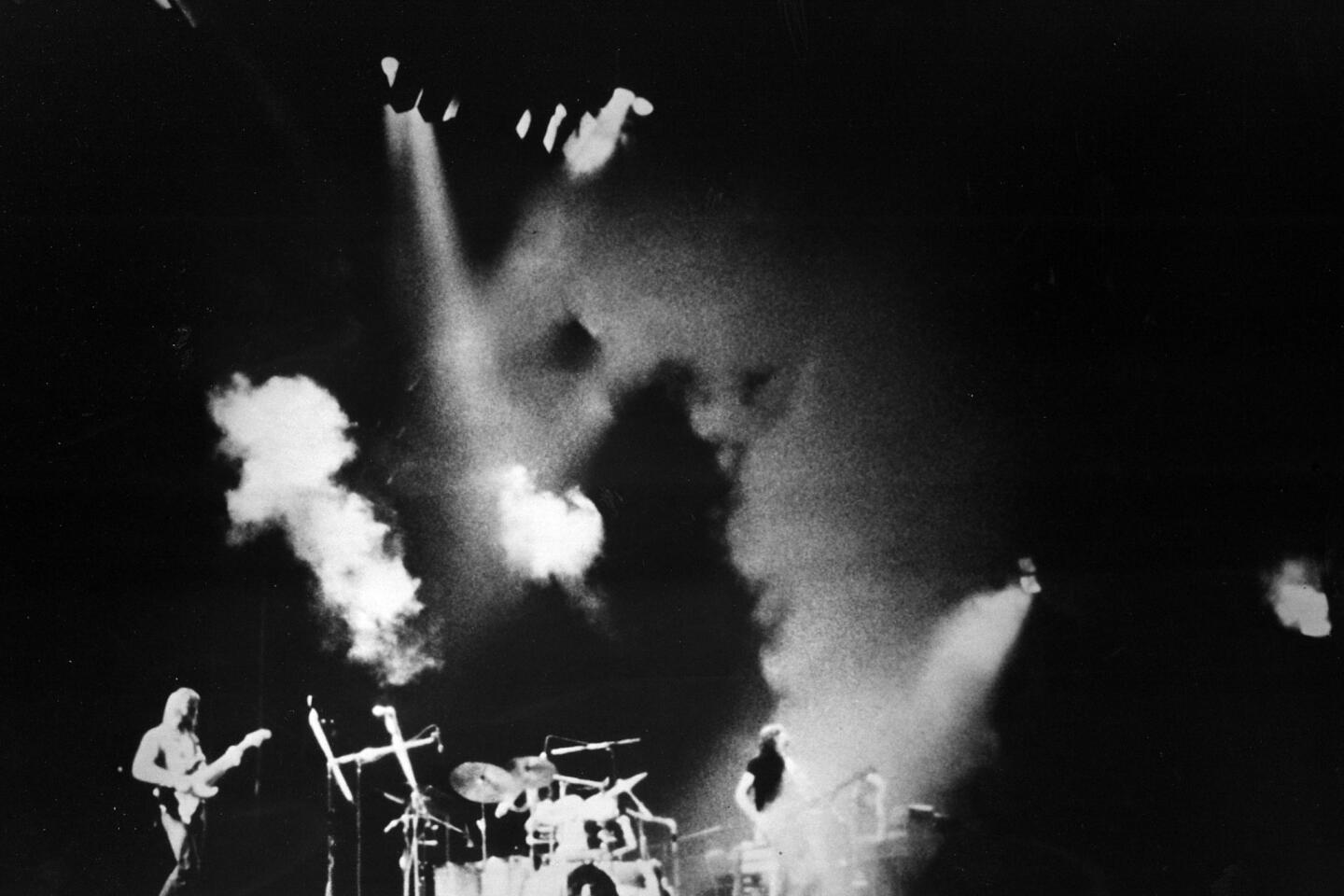

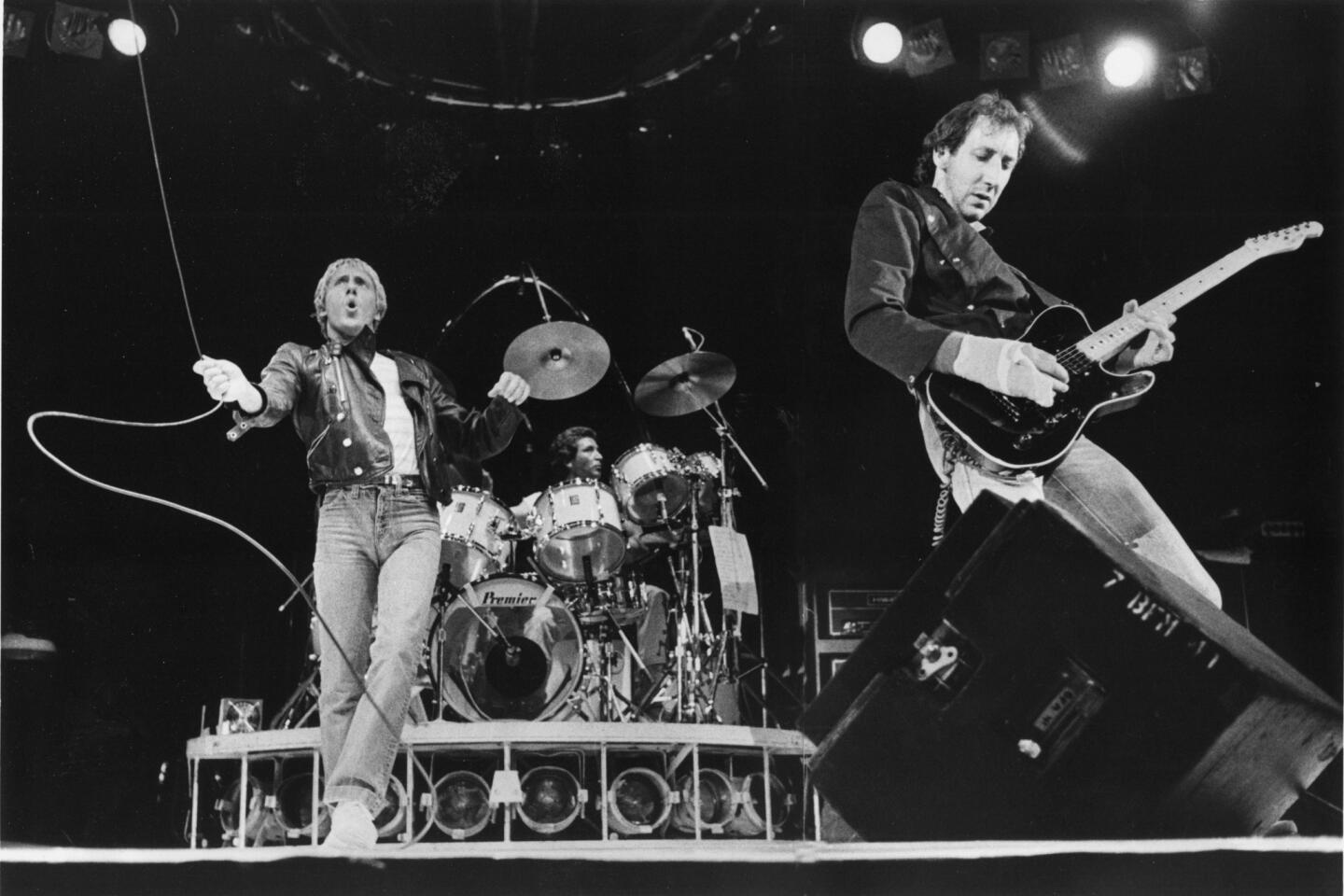

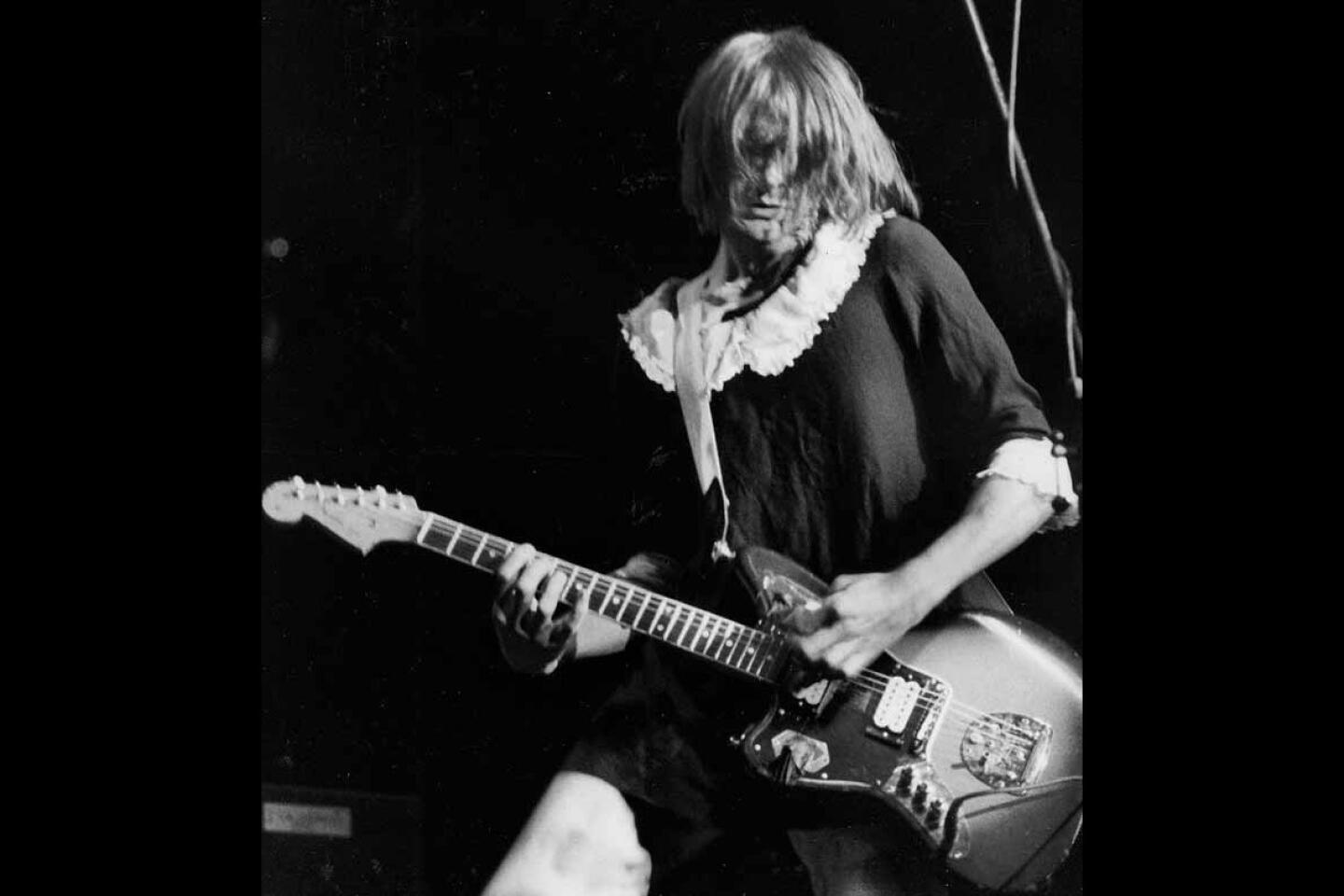

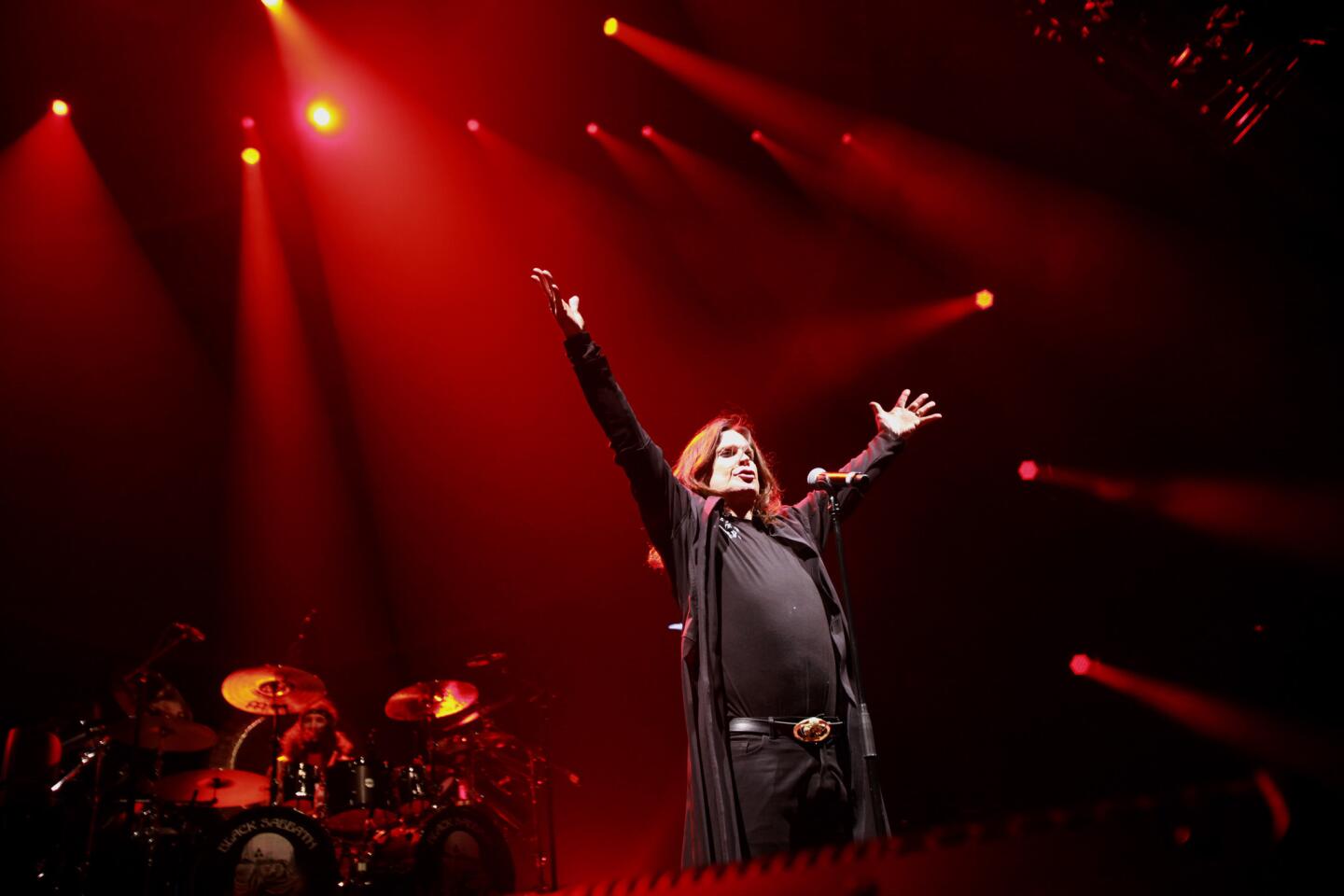

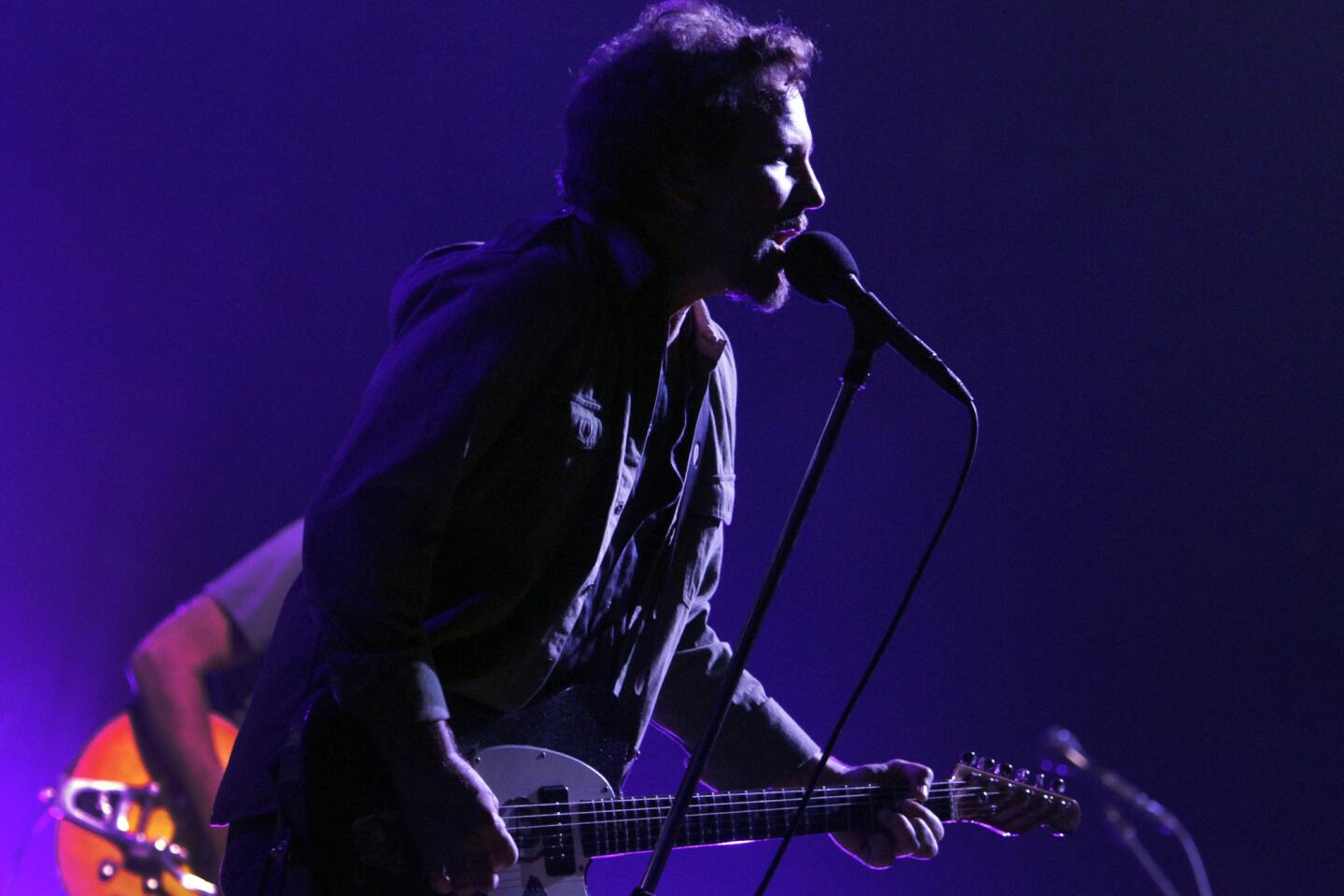

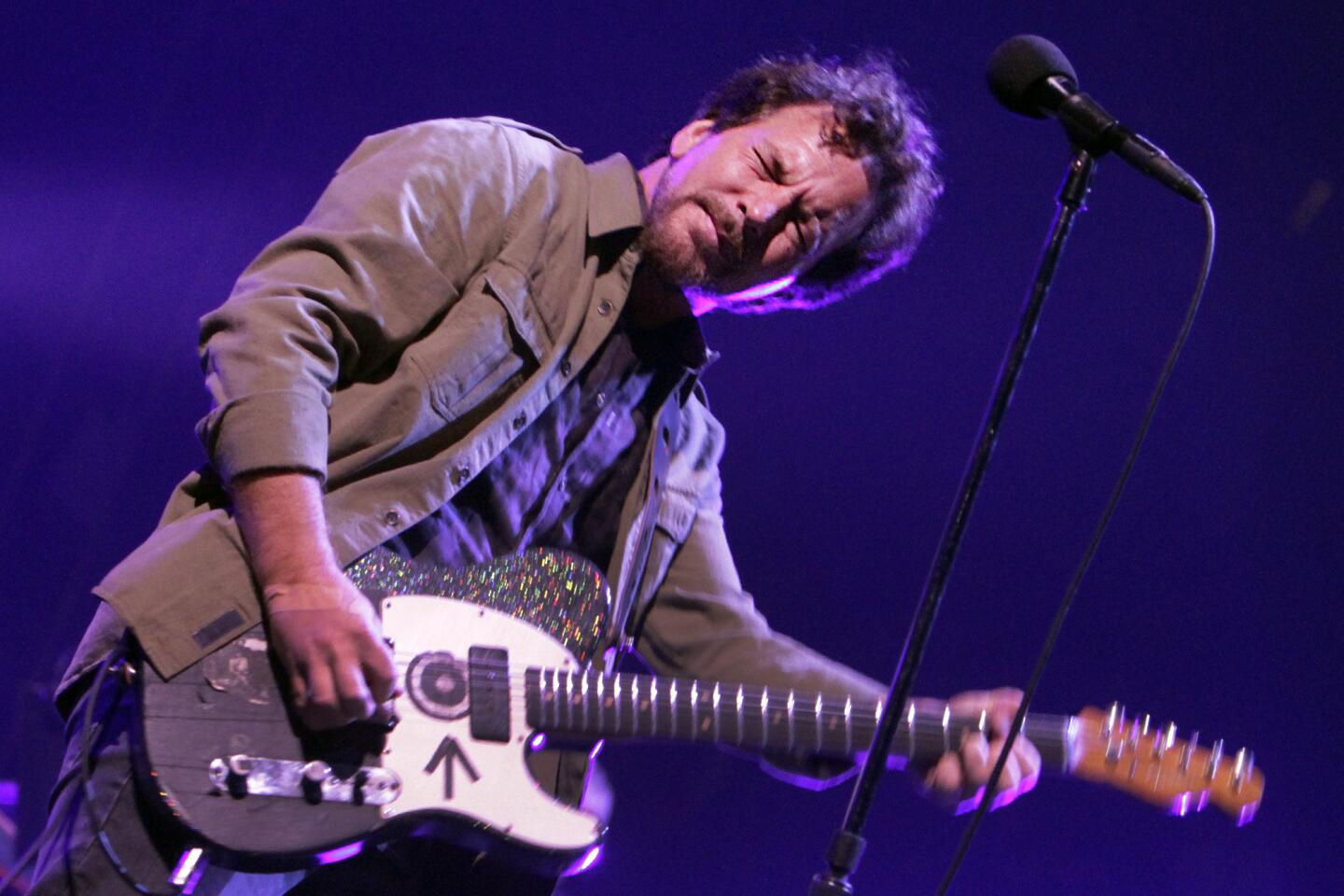

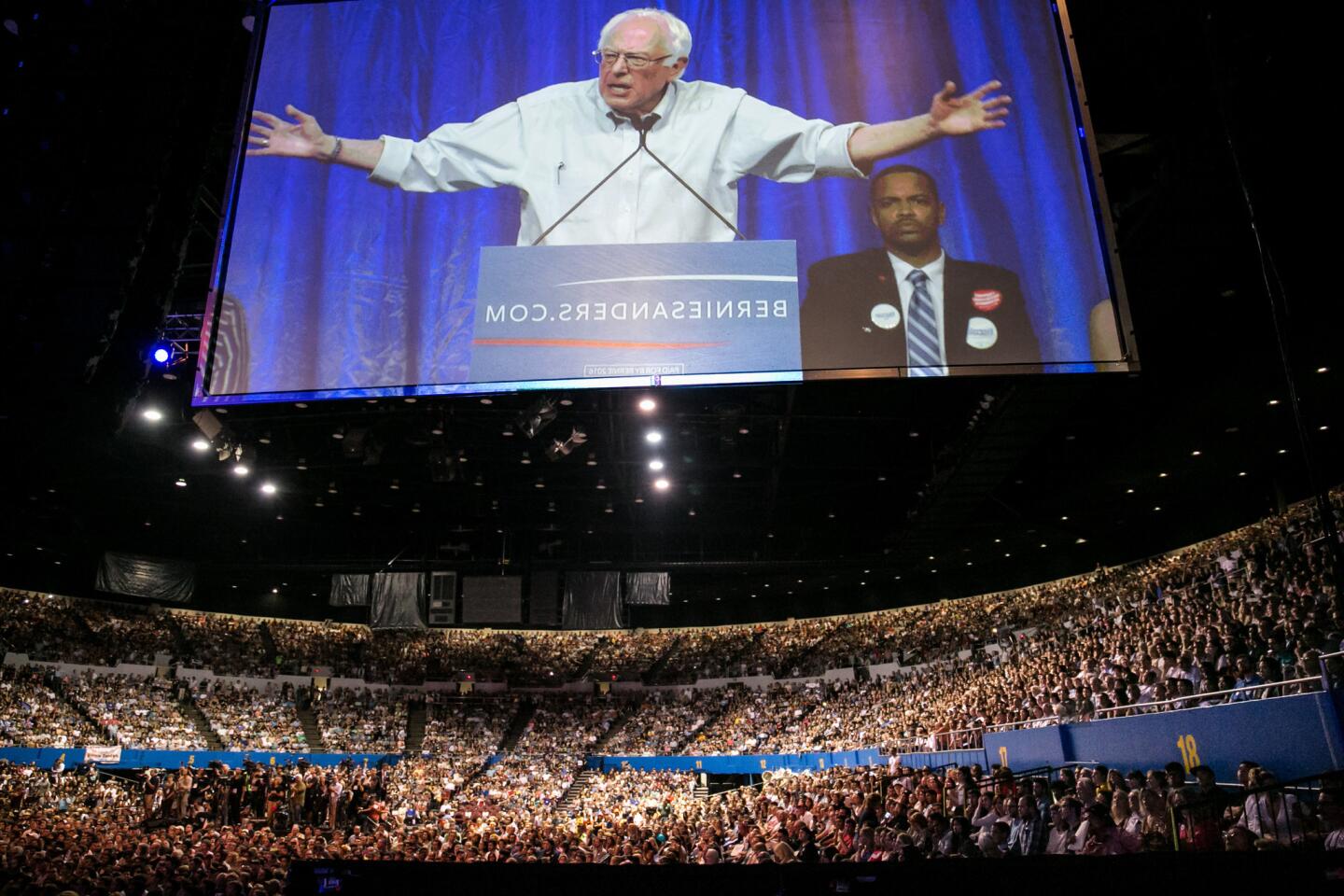

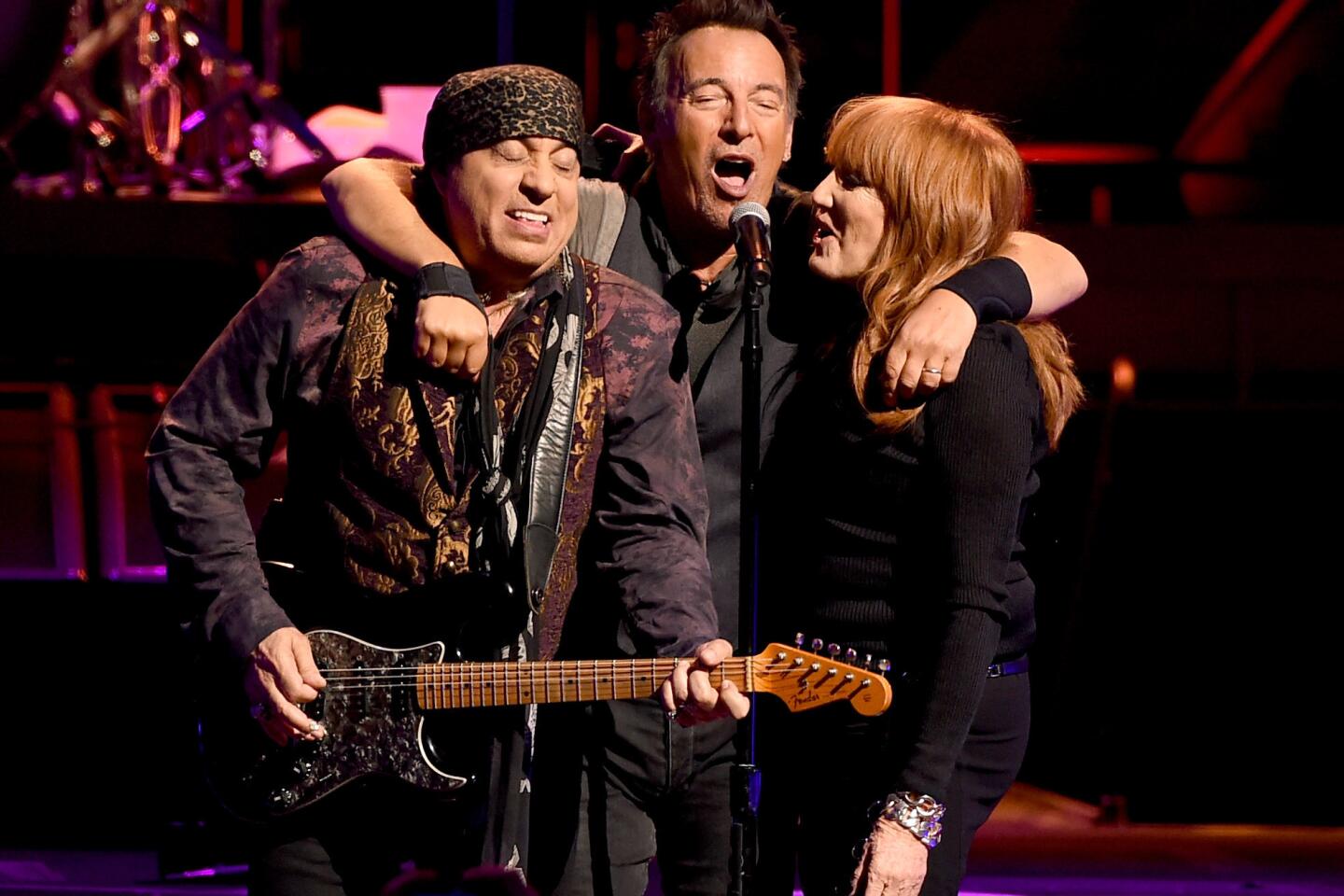

Bruce Springsteen famously christened the arena “the dump that jumps,” choosing it over other venues and playing a three-night stint in March, one of its last operating months. And the arena received praise from locals for booking acts such as the Killers, Green Day and Pearl Jam, even if one reviewer described it as a “concert hall at a summer camp.” A rally last year for former Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders drew a passionate crowd of nearly 30,000 to the arena.

Nonetheless, those with a soft spot for the building can’t help but agree that its moment has passed.

“It had that old-school vibe and that’s what I loved about it,” said Danny Hizami, owner of Figueroa Philly Cheese Steak, which sits across the street from Exposition Park. “It was nostalgic, it had history. I guess you could call it the Wrigley Field of indoor stadiums because it was just so old and so kind of authentic and cool.”

It was the arena that hosted Hizami’s first concert, a performance by a snarling, strutting Pat Benatar. Yet the 48-year-old is among many area business owners who say the arena’s heyday is long gone and look forward to the state-of-the-art soccer stadium set to take its place. By 2018, they hope the incoming MLS expansion team will bring a much-needed stimulus to the neighborhood.

Even the design architect of the Sports Arena embraces the future plan, although he lamented that demolishing the structure was “no worse than having my foot amputated.”

At 28, Louis Naidorf was assigned to draft a plan for the Sports Arena and had one week to create a building that came with a list of unusual demands: seats high enough to be safe for a rodeo, a roof tall enough for a circus, pipes that could handle refrigerant to freeze the floor, 130,000 square feet of floor space.

It also had to fit into an already excavated hole that the city had dug because it needed the dirt to help construct an extension of the 110 Freeway. “Another stroke of civic genius,” said Naidorf, now 88.

The result was no-frills, but functional and inspiring enough to land on the cover of the telephone directory and nab design awards.

But the luster is long gone, Naidorf acknowledged. He last saw the arena a few years ago.

“It was looking a little dilapidated, like it had lost its spirit,” he said. “It’s at a point where it can go quietly in hospice and make way for some vibrant thing that will serve the people of Los Angeles well. It’s done its job.”

ALSO

Amid swelling homelessness, Santa Ana turns an old bus terminal into a shelter

Protesting tenants of a Highland Park apartment complex face a mass eviction

If Proposition 55 passes, the state budget will rely even more on California’s highest earners

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.