With women in a supermajority, L.A. County supervisors are no longer the ‘little kings’

- Share via

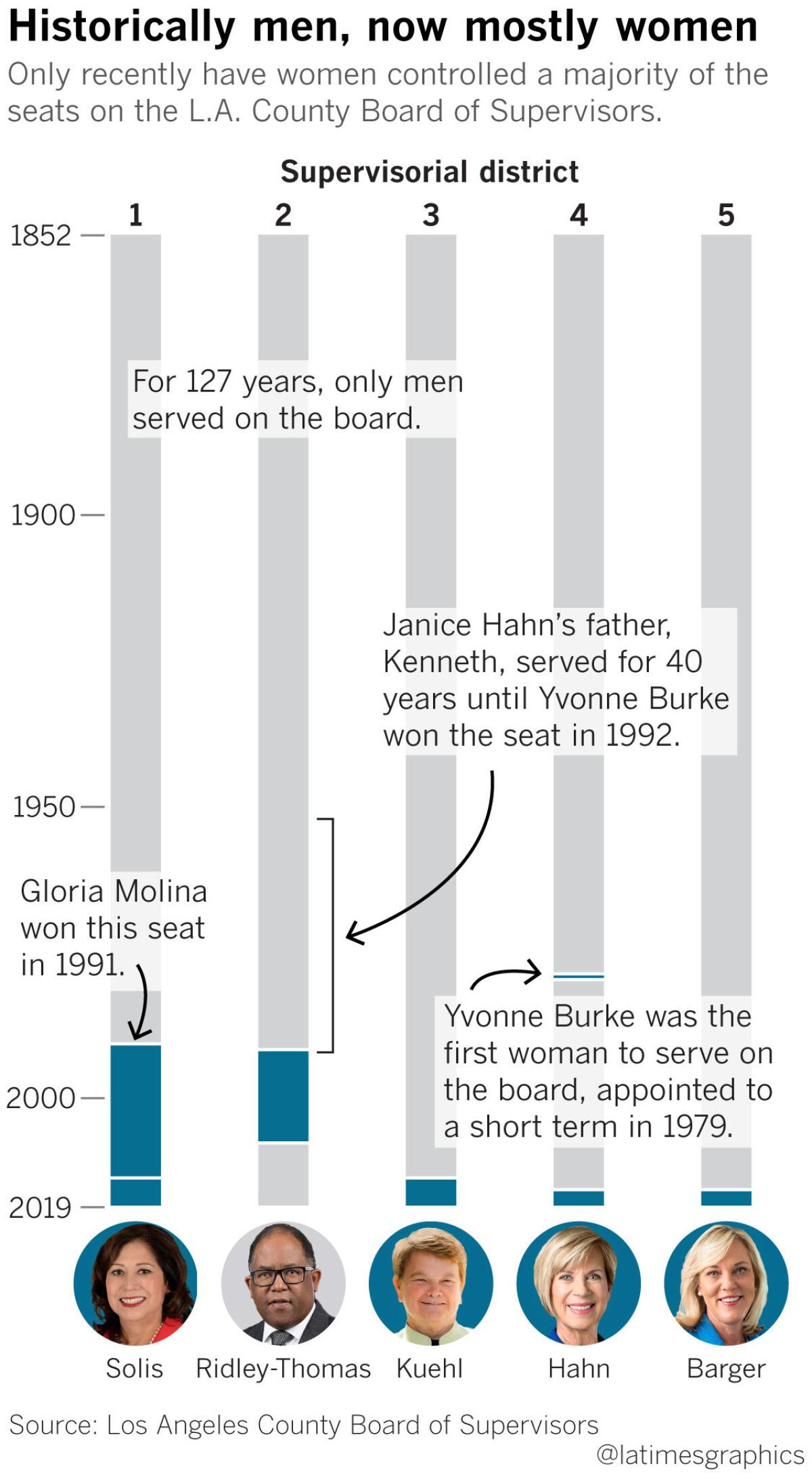

For more than 150 years, Los Angeles County’s Board of Supervisors has been the realm of men — a powerful governing body that long ago earned the nickname of the “five little kings.”

But that was before women earned a supermajority on the board, with Supervisor Janice Hahn — whose father, Kenneth Hahn, had the same job from 1952 to 1992 — now serving as chair. It’s a shift that has accompanied increasingly progressive stances on a host of issues, including housing policy and criminal justice reform, but especially on issues that specifically affect women.

Someone apparently forgot to tell all of this to Sheriff Alex Villanueva.

In an extraordinary exchange during this week’s board meeting, the newly elected sheriff ran into an unusually stiff wall of resistance as the female supervisors upbraided him over a decision to reinstate a male deputy who had been fired amid allegations that he abused and stalked an ex-girlfriend.

“If I sound critical, it’s because I am,” said Supervisor Sheila Kuehl. “But it’s mostly because I’m worried. I’m really worried and concerned about the message that is being sent.”

Though certainly notable as a rare public rebuke of the county’s top cop, the meeting marked the second time in a month that the board has tangled with county officials over issues related to gender. Supervisors also have pushed to recruit more women to county agencies and to implement more vocational training for women and female youths incarcerated in county facilities.

“I’m aware of it every single time that I look at this board,” said Hahn, who works at the county administration building named after her father. “I know that this is not my father’s Board of Supervisors. It is historic, and I do think it makes a difference in so many areas.”

The women serving on the board now — Supervisors Hilda Solis and Kathryn Barger, in addition to Hahn and Kuehl — form a bloc that sets the priorities and policies of county government, a low-profile, but powerful tier of public agencies with a collective budget of $30 billion and jurisdiction over courts, jails and social services.

Only six women have served on the board since it began in the 1850s, with the current group preceded by Gloria Molina, elected in 1991, and Yvonne Burke, elected in 1992. But, with the addition of Hahn and Barger in 2016, this is the first time there has ever been four female supervisors on the five-member board at the same time.

Their life experiences with childbirth and motherhood, and with navigating discrimination in the workplace and in society, at large, have helped shape their priorities on the dais, they say. And it is happening at a time, in the #MeToo era, that institutions across the country and state are grappling with issues of gender equality and sexual misconduct.

The discussion with Villanueva is just one example.

Three weeks ago, supervisors also clashed with county officials over a long-standingl plan to relocate female prisoners to a new, 1,600-inmate jail near Lancaster, about 80 miles north of downtown.

In addition to a desire to incarcerate fewer women, the supervisors said they worried that the remote location could isolate women awaiting trial and complicate visits from children and other family members.

Amid those concerns, the county has delayed the multimillion-dollar project, which had been close to breaking ground but now seems in peril.

“This is a new board of supervisors,” Hahn said during that meeting. “We know that the direction we’re going to take. L.A. County is going to be different.”

Another example happened during a weekly meeting of the board two years ago, when the four female supervisors donned headbands from the film “Wonder Woman” to raise awareness about recruiting women to the L.A. County Fire Department.

Out of more than 2,500 firefighters, only a few dozen are women, they noted, and some stations aren’t even equipped with separate bathrooms, locker rooms or sleeping areas.

At the time, Hahn pressed Fire Chief Daryl Osby to retrofit the Marina del Rey station, which is in her district, and to recruit more women.

“The chief was very aware that there were four women on the dais who were very serious,” she said. “I’m not sure a previous board would have made that a priority.”

Three years ago, Kuehl and Solis promoted a five-year initiative that directs dozens of county departments to address the disadvantages facing women and girls. The broader bloc of female supervisors also has pushed for more options for vocational training for women and female youth who are incarcerated in county facilities.

“I don’t think there is any doubt that having even one woman on a board makes a difference, if she’s allowed to speak up and speak from her own experience,” Kuehl said. “Certainly, having four women on the board, I would think, is somewhat intimidating.”

To be sure, gender is not the only issue at play on the Board of Supervisors. Kuehl is gay, Mark Ridley-Thomas, the board’s lone male, is black and Solis is Latina — all of which are reasons that the supervisors are, as a whole, sensitive to progressive issues, some political observers say.

But the supervisors say they aren’t blinded by their own biases. Barger, for example, is married to a retired sheriff’s deputy, yet she brought forward the motion that compelled Villanueva’s testimony this week.

“I’m not trying to do an ‘I got you,’” Barger told the sheriff. “[But] I couldn’t, especially with the board a majority of women, not challenge those statements.”

At that meeting, both Hahn and Ridley-Thomas were absent because of illness, and the sheriff encountered extraordinary pushback even though he is independently elected and does not report to the board.

The remaining three female supervisors pressed from the dais about whether the fired deputy, Carl Mandoyan, who also volunteered on Villanueva’s election campaign, should have been rehired amid allegations that he abused a former girlfriend in 2014.

During a few testy exchanges, the sheriff interrupted the supervisors at times and quibbled with Barger over whether the woman who made the allegations should be called a “victim.”

Villanueva said he disagreed with the board about the facts of the case, which remain unclear because of the confidentiality of personnel files of law enforcement officers in California. He said the case against Mandoyan was the result of a flawed disciplinary process that can lead to unfair termination.

“An all-male board, earlier, may not have thought the same way,” the sheriff told The Times after the meeting in response to a question about the makeup of the board. “But they have a very valid point, and we want to make sure we’re protecting the rights of everyone who’s in a vulnerable position. But we have to protect the rights of everyone. We can’t pick and choose who we afford that protection for.”

Villanueva and supervisors remain at odds — and it’s an issue that might not fade quickly. In two weeks, the county’s lawyers are expected to report back with more information about the case after the board passed a motion directing them to do so.

The makeup of the board is expected to remain the same until next year, when an election to replace the term-limited Ridley-Thomas could well give women complete control of governing Los Angeles County.

So far, former L.A. City Councilwoman Jan Perry has entered the race, as has City Council President Herb Wesson. Soon-to-be-termed-out state Sen. Holly Mitchell also is strongly considering a run, according to two people familiar with her thinking.

If such a shift away from a male-run board happened, it would be historic for L.A. County and California, though six other counties in the state do have female-majority boards, including Contra Costa, El Dorado, Marin, Modoc, San Bernardino and Sonoma counties, said Sara Floor, a spokeswoman for the California State Assn. of Counties.

Also, just two of the 15 members of the Los Angeles City Council are women, and women only represent about a quarter of the California Legislature and officials elected to statewide office.

“If that were to happen in Los Angeles, that would be a real signal,” said Jennifer Piscopo, an assistant professor of politics at Occidental College who has studied gender dynamics in governance. “It would cause buzz, and it would get attention, and it would be a real moment.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.