Must Reads: The world’s largest pot farms, and how Santa Barbara opened the door

- Share via

In a sandy draw of the Santa Rita Hills, a cannabis company is planning to erect hoop greenhouses over 147 acres — the size of 130 football fields — to create the largest legal marijuana grow on Earth.

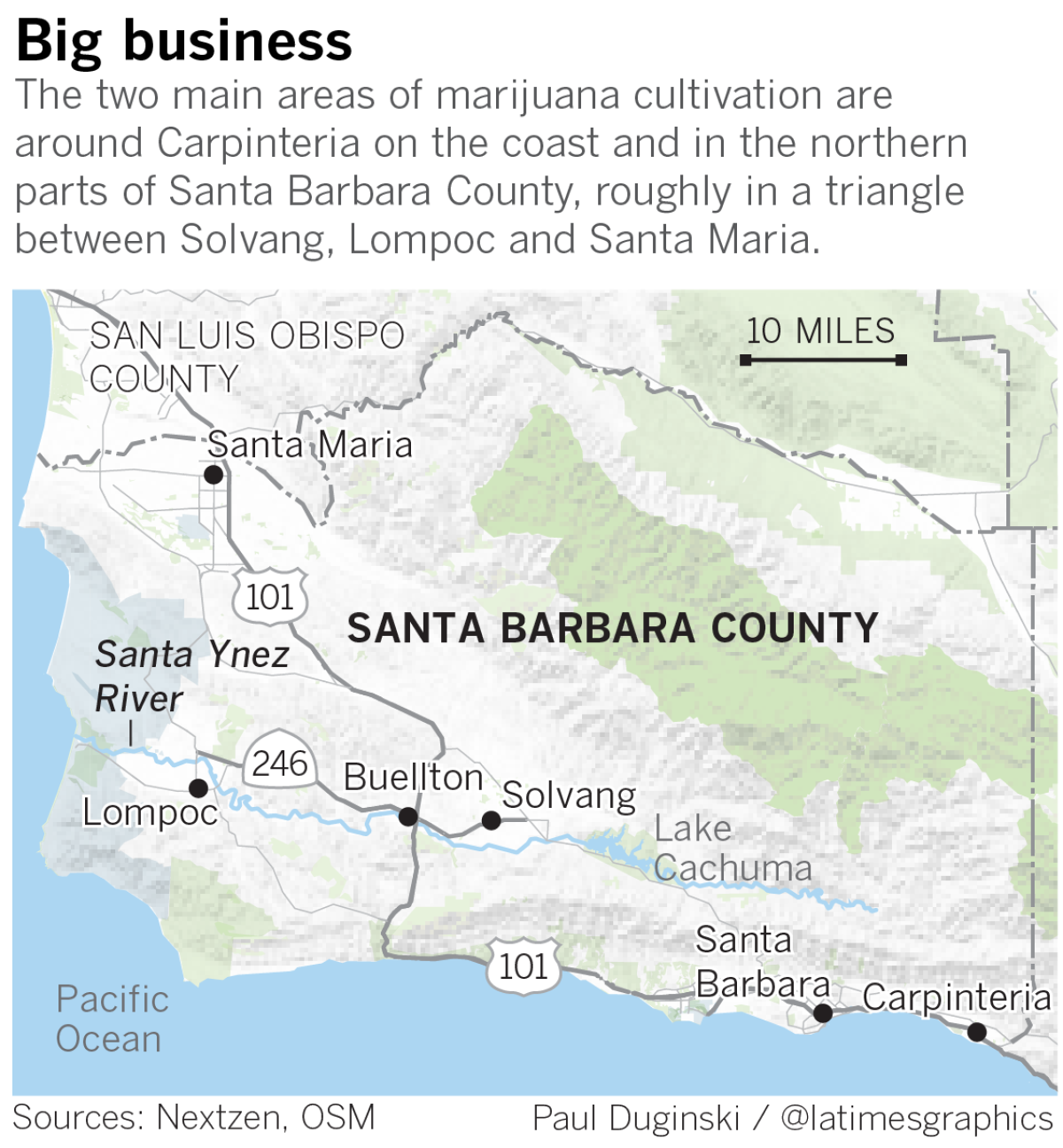

Across the Santa Ynez River, two miles away, a farmer is planting the planet’s second-biggest grow, at 83 acres. Several operations are already as large as what industry trackers say are the world’s other behemoths, in Colorado and British Columbia, with a dozen more slated to be much bigger.

Santa Barbara County’s famed wine region — with its giant live oaks and destination tasting rooms — and the quiet beach town of Carpinteria have become the unlikely capital of California’s legal pot market.

Now row after row of white plastic hoop houses sprawl amid rolling vineyards and country estates, and coastal bungalows and schools carry the whiff of backcountry Humboldt.

Lobbied heavily by the marijuana industry, Santa Barbara County officials opened the door to big cannabis interests in the last two years like no other county in the nation, setting off a largely unregulated rush of planting in a region not previously known for the crop. County supervisors voted not to limit the size and number of marijuana grows. They chose not to vet growers’ applications for licenses or conduct site inspections.

They decided to tax the operations based on gross revenue instead of licensed square footage, as Humboldt and Monterey counties do, even though the county has no method to verify the numbers. So far, the county has received a fraction of what its consultants had predicted.

Santa Barbara County officials are not alone in trying to lure cannabis cultivation. But the other local governments seeking this revenue stream are mostly in remote, economically depressed regions, not high-priced coastal and tourist areas.

In Santa Barbara, growers and their hired advocates developed close ties to two county supervisors, Das Williams and Steve Lavagnino, who pushed for and won nearly every significant measure the cultivators asked for. A third supervisor elected in November, Gregg Hart, hired a marijuana lobbyist as his chief of staff.

The cannabis boom has caused a backlash from residents and vintners afflicted by the smell, and farmers who worry that spraying their avocados could make them financially liable for tainting multimillion-dollar marijuana crops. Fearing for their businesses and quality of life, they have organized into activist groups, hired attorneys, filed lawsuits and zoning appeals.

The county is now trying to rein in the industry with stricter regulations and law enforcement.

California voters passed Proposition 64, legalizing recreational marijuana, in November 2016. In the ensuing 16 months, Santa Barbara County supervisors worked on plans to regulate and tax the industry, while allowing it to vastly expand under temporary licenses.

The open window, combined with no limits on crop size, drew companies with the means to invest millions of dollars.

Farms in Santa Barbara County hold 35% of all cultivation licenses issued in California this year, despite the county having only 1.8% of the state’s land. Humboldt County, the historic center of the marijuana universe, has 22%, while illegal grows there continue to dominate the larger black market.

Santa Barbara County officials say the industry will boost the agricultural economy, provide jobs and shore up government coffers.

Williams said the revenue from the cannabis tax allowed the county to create a sheriff’s enforcement team that began eradicating illegal grows in August. “Thirty-five raids in a small county is a lot,” he said.

He envisions the county fostering an industry that obeys the law, pays its taxes and solves problems affecting its neighbors. He conceded that the board’s actions helped create a “Wild West situation that we’re just cleaning up now.”

“Our community is painfully divided about how to bring this industry under control,” he said.

At the south end of the county in Carpinteria, the skunky odor of marijuana pours out of the open vents of steel-frame greenhouses that the cut flower industry used for decades. Residents said the irritant makes eyes water and chests tighten. Some complain of headaches and nausea.

Casey Roberts, 61, who has taught at Carpinteria High School for 33 years, said the smell comes and goes. It’s worse in the morning, he said, and it doesn’t seem to have changed much with the odor control systems. “Every day you get that scratchy throat,” Roberts said.

The county mandated that growers in the Carpinteria Valley, which sits on unincorporated land surrounding the city, install odor control systems as part of their land-use permits, and though the rule has not gone into effect, at least 12 of the 23 operations have done so, according to officials. But how much of the odor has been contained or neutralized is difficult to ascertain.

Joan Esposito, 76, lives across from a greenhouse and says the smell still “permeates everything.”

Odor control systems are not required outside Carpinteria in the more rural wine country.

In the Santa Ynez and Santa Maria valleys, the smell of pot can overwhelm the wine tasting rooms downwind of grows, while vast rows of polythene hoop houses have become eyesores on the pastoral landscape, threatening the tourism-dependent economy of one of the nation’s top viticulture zones, famous to non-connoisseurs as the setting of the 2004 movie “Sideways.”

“The skunk smell is a deterrent to other animals and humans,” said Tyler Thomas, the winemaker at Dierberg, which sits on a wedge of land surrounded by 230 acres in the permitting process for pot. “We have human beings coming to our tasting room we don’t want to deter.”

Farmers closest to cannabis came to realize they can no longer spray pesticides without fear of being held liable for contaminating neighboring cannabis grows. By law, marijuana must be destroyed if it tests positive for pesticide.

“The pesticide levels set for cannabis are extremely low,” said Rick Shade, who manages 600 acres of avocado trees in the Carpinteria Valley.

Marijuana growers agreed to sign a contract to not hold farmers liable for their crops if they spray during a specified time period. But commercial crop dusters last month decided they didn’t want to take the risk.

Sharyne Merritt, who has 13 acres of avocados, says even the organic spray she normally uses is banned for cannabis and the only acceptable one “is completely ineffective.”

“The cannabis growers will make tons of money while I’m going to lose half the value of my crop,” she said. “No one seems to have thought this through.”

Graham Farrar, a Carpinteria Valley grower and president of the Carp Growers cannabis coalition, said he and his members would continue to look for a solution.

Many of the Carpinteria-area cannabis growers were in the flower industry, he said, and have deep ties in the town. “It’s really in our best interest to make our neighbors happy,” he said. “I like to walk into the coffee shop with my head held high.”

The rush to profit from cannabis in Santa Barbara started during a moratorium on new grows.

On Feb. 14, 2017, county supervisors cleared the way: Anyone who said they had been growing medical cannabis on or before the day the moratorium was passed — Jan. 19, 2016 — could continue to cultivate the same amount on the same land if they signed into a registry that would grandfather them in.

The growers did not have to provide any evidence that they owned or leased the property at the time, much less that they were cultivating cannabis there.

This registry became the de facto list of legal growers in the county.

When the state announced in the fall of 2017 that it was going to issue the first temporary cultivation licenses, the county turned to the registry to determine eligibility. Those on the list just had to sign an affidavit under penalty of perjury that they were growing medical marijuana on their site prior to Jan. 19, 2016.

The supervisors rejected a measure recommended by the planning commission to have staff ask for documentation and research the veracity of the statements.

The affidavit became the only documentation the California Department of Food and Agriculture was given to issue the state license. Santa Barbara was the sole county to rely just on an affidavit.

Proposition 64 stipulated that large-scale grows not be licensed until 2023 to give small, local operators a chance to establish themselves before big corporate interests entered the market. State agriculture officials issued licenses for small grows of 10,000 square feet or less of planting space and medium licenses for up to an acre. But they allowed a loophole: Growers could stack as many of the small licenses as they wanted, leaving it to local jurisdictions to set limits.

When Santa Barbara County supervisors decided to allow unlimited licenses, moneyed interests from all over the state saw an opportunity.

The state licensing authority was suddenly deluged with applications for sites in Santa Barbara County — many filed by companies from Northern California and Los Angeles. All claimed they had been growing in Santa Barbara since January 2016.

In the Santa Ynez Valley wine region, long tunnels of hoops began popping up last year. Just three weeks after the vote not to set limits, Iron Angel II registered with the state as a limited liability company based in Agoura Hills. By the end of the year, it had 265 small licenses — plus a single medium license — allowing it to grow 60 acres altogether.

Another grow, a 30-acre greenhouse complex north of Buellton, had more than 600,000 plants before it was raided for reasons the Sheriff’s Department would not reveal.

Stefanie Keenan said the rush to plant caused a surge in land values that has kept potential small growers like her and her husband out of the market. “They’re charging $10,000 an acre a month to grow marijuana,” said Keenan, who lives in Buellton. She urged the supervisors to start with a pilot program of local growers that would have less of an impact in communities. “You could have eased people in. But this is so in your face.”

Blair Pence said the field next to his winery on Highway 246 in the Santa Rita Hills had been planted with bell peppers until the spring of 2018. Now cannabis is growing on 30 of those acres and the sharp odor rolls down the canyon to his home and tasting room.

He said another grow popped up on the parcel on the other side of his neighbor’s land, along with two more across the street and numerous others along the highway between Buellton and Lompoc — all in 2018, two years after the operators claimed they were already growing there.

“These guys are all lying through their teeth,” Pence said.

A review of the sites on Google Earth confirms his observation that many farms were not there when the affidavits said they were, including one operated by a member of the county agricultural advisory board, John De Friel, who is applying for permits to grow 83 acres this year. De Friel did not respond to requests for comment.

Dennis Bozanich, the deputy county executive officer in charge of developing cannabis regulations, said that the sheriff has eradicated about 20 licensed farms because the operators lied on the affidavits about having grown since Jan. 19, 2016, and that investigations into others are ongoing.

The state temporary licenses are expiring this year. The county now requires growers to go through its land-use permitting process, which gives neighbors a chance to appeal. (But while that process is underway, temporary license holders, with the county’s consent, can get a state provisional license that allows them to grow for another 12 months.)

Every extra day helps. A 20-acre harvest could make over $40 million.

The county is now quickly approving the longer-term grows. Those operations will be subject to more regulation than the last two years, officials say. They will have to tag and inventory every plant, a state requirement to ensure they pay taxes and sell only to licensed distributors.

For the Carpinteria area, supervisors set a 186-acre limit because of residents’ complaints about the smell. But elsewhere, the only limit on acreage is what the market will bear.

In early May, Pence’s attorney learned that the county had approved a land-use permit for a 50-acre marijuana grow, bigger than any in Colorado or Canada, across the street from the winery.

“I never received any notice from the county,” Pence said. “I had one day to appeal.”

The cannabis policy was developed largely by Bozanich and supervisors Williams and Lavagnino. The two supervisors formed an ad hoc committee — not subject to California’s open-meeting laws — that guided Bozanich and planning staff in writing temporary measures and, ultimately, a broad ordinance regulating the industry.

At board meetings, Bozanich, Williams or Lavagnino floated concepts they had already discussed with growers — like the registry — and growers lined up to support them during the public comments. Though there were numerous public hearings, few residents attended most of them, and many people were later caught unaware by the scope of the cultivation, failing to anticipate the consequences of the incremental measures being passed.

The supervisor who regularly opposed the industry’s agenda, Janet Wolf, retired in January and said the board’s actions felt less like a policy debate than a “fait accompli.”

“Bottom line, people didn’t understand the implications of anything that was going to happen,” she said. “We’d never taken on a huge land-use issue and do it by an ad hoc committee in the 12 years I was on the board.”

Emails and calendars released to The Times through the state public records act show marijuana lobbyists and growers had easy and regular access to Williams and Lavagnino.

Erin Weber, a cannabis consultant with California Strategies, a Sacramento-based lobbying firm, drafted a letter last year for Williams to send to the Coastal Commission, urging it to certify the county’s cannabis regulations in the coastal zone.

“This is very faithful to what we discussed,” Williams responded in an email. “We will submit it without changes.” He told The Times that because the anti-cannabis side also supported the regulations, he saw no problem with signing the letter.

In the fall of 2017, Weber and her colleague Jared Ficker were lobbying hard to let growers on the registry cultivate with no limits. Williams’ calendar contains an entry on Sept. 4 for “Sailing Trip/Diving” with Ficker and Williams’ wife.

When the planning department last year recommended a measure that the marijuana farmers should bear all the costs of appeals to their permits filed by neighbors, the cultivators emailed Williams that it was unfair and urged him to reject it. “Don’t worry, I’ll fix it with a 50-50 recovery model. Don’t tell anyone though,” he wrote to grower Mike Palmer.

“On it,” he wrote to Farrar, the president of Carp Growers, “We will cost split it if I get my way.”

“Thanks Das,” Farrar replied.

The move would have put half the cost of county staff time — as much as $14,000 for a single appeal — on the grower and half on the person making the appeal.

Instead, the supervisors decided not to vote on the staff recommendation, saying it was unfair to growers, and left the county to bear the entire amount.

Williams met frequently with Farrar. He wrote a letter of recommendation on Farrar’s behalf to Culver City, where the grower was seeking to open a dispensary.

The two also socialized.

“Hey man,” Farrar emailed Williams in September 2018, a couple of months after the appeal measure was shot down, to recommend shows they might see at the Santa Barbara Bowl. “The National — this will be awesome.. i’ve got an event before so not sure if i can make it but definitely will if i can.”

In 2017 and 2018, members of Carp Growers gave a total of $16,500 to Williams’ campaign committee, and they donated $12,000 to Lavagnino in the month leading up to the final vote on the cannabis ordinance last year.

Both Williams and Lavagnino said the contributions and relationships did not influence their decisions.

“I have friends on the other side of this, too. This is a small community,” Williams said.

Emails suggest Farrar had a relationship with Lavagnino as well, even though the supervisor’s district is on the opposite end of the county as Carpinteria. They attended a fundraising dinner together in Santa Barbara for the Special Olympics in October. That morning, Farrar wrote to the supervisor: “Hey man — happy Sunday ... what are you thinking for tonight? When do you want to get there? Drinks before?”

Lavagnino has said repeatedly that the county’s goal was to bring an illicit industry into the light and make it pay taxes. The supervisors drafted a tax measure that voters passed requiring growers to pay 4% of their gross receipts to the county.

This had a couple of advantages over taxing by square footage: Growers would not have to pay for failed crops, and operators who ran their own distribution and retail ventures would be taxed just once, at the final sale. But for the time being, the county had a system in which they had no idea how many plants were grown, nor how much product was sold.

In February 2018, a consultant for the county, HdL Cos., estimated the county would collect between $15 million and $21 million in taxes annually from the 47 acres licensed to grow at that point. If that acreage expanded, so would the tax stream. That month, Lavagnino urged two of his skeptical colleagues to pass a tax referendum and land-use policy so the county could reap the rewards.

“I’m trying to generate what could be $20 [million] to $40 million a year for the county,” he said.

By the end of 2018, the acreage licensed had grown to more than 630 acres. Even if only a quarter of that were cultivated, the county would be due between $24 million and $36 million annually in taxes, using the consultant’s formula and a price per pound of $500 to $750. But for the three tax quarters collected so far, covering the peak of the harvest season, the county has received only $4.6 million.

“We’ve been somewhat flying blind,” Bozanich said.

He said that will change later this year as growers come into compliance with the ordinance passed last year and must register every plant with the state.

Statewide cannabis industry leaders say there are not enough licensed dispensaries in California to buy what is being grown.

“It’s either going to leak into the informal market or rot in warehouses,” said Hezekiah Allen, a cannabis lobbyist who headed the California Growers Assn. for four years and now serves on the board. “This is absolutely ludicrous in terms of volume.”

“We think it takes 1,100 acres to supply the entire state,” he said.

By the end of May, the growers in Santa Barbara County had applied to plant 1,415 acres.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.