After L.A. cleared out homeless encampments, here’s what happened to some Tujunga Wash dwellers

Dave Curry, right, visits his friend Russell Badgwell in Tujunga Wash, the place he used to call home. Curry received a Section 8 voucher from a San Fernando Valley housing agency and now lives in an apartment.

- Share via

After a decade in the riverbed, Dave Curry was ready to try living under a roof.

With the help of a San Fernando Valley housing agency, Curry got a Section 8 voucher and went looking for an apartment.

He was a few weeks into his search when his campsite in Tujunga Wash was demolished. Curry was one of about 30 men and women uprooted last fall in a series of cleanups conducted by the city of Los Angeles and nearby residents.

Dave Curry lays on the floor and plays with his dog, Boo, in his new apartment. With the help of a San Fernando Valley housing agency, Curry got a Section 8 voucher and found an apartment in Sunland.

A few slipped back into the wash. But most dispersed, leaving no record of where they went or how their lives changed.

It’s a story that was repeated nearly 1,000 times last year, on scales large and small: Tents and shopping carts appear, residents complain, sanitation crews arrive to clear away the camps. But where did the displaced people go?

NEWSLETTER: Get essential California headlines delivered daily >>

In the absence of an official account, the presumed answer is that they went somewhere else, to another street, another alley, another drainage ditch.

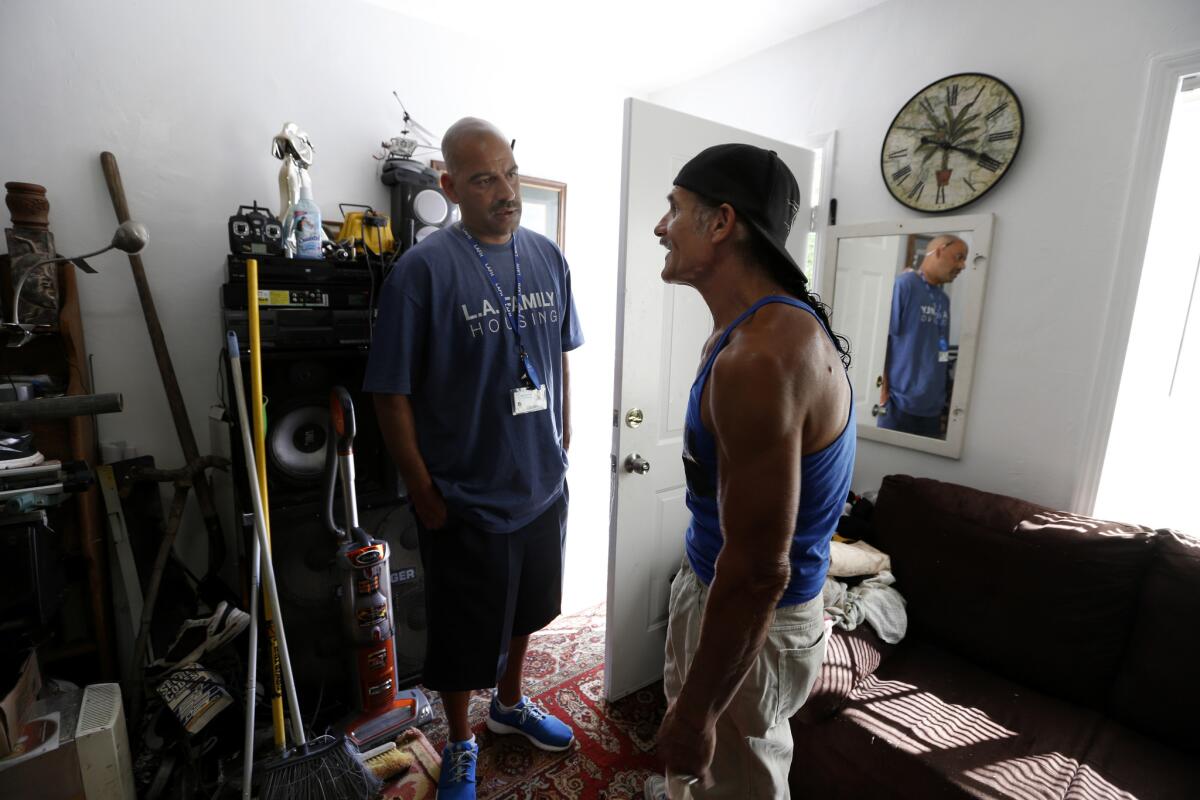

Eric Montoya, a L.A. Family Housings outreach worker, left, speaks with Dave Curry in his new apartment in Sunland. After a decade in the riverbed, Curry was ready to try living under a roof.

But that’s not always the case, and it wasn’t in the wash. Like Curry, many of the wash dwellers were already working with the housing agency in the hope of regaining a traditional life. Some have succeeded in getting housing. Seven months later, others are still struggling with bureaucratic and human obstacles.

To illuminate the difficult path out of homelessness, LA Family Housing, the agency that was working with Curry, obtained permission from several of the Tujunga Wash dwellers to tell their stories.

::

Eric Montoya, LA Family Housing’s outreach worker in Tujunga Wash, parked the white van on Big Tujunga Canyon Road. Montoya hiked a quarter-mile over sand and boulders, crossing the creek then flush with spring runoff.

Valery Tash visits her friends in Tujunga Wash. Although she lives in a shelter, she says she prefers to spend time in the wash because it is more peaceful than the shelter.

In a clearing cut out of tall shrubs, he found Russell Badgwell, sun-bleached hair cascading to his shirtless shoulders, sitting on a beach chair beside his tent while sausages crackled on a propane camp stove.

The purpose of the visit was partly pep talk and partly a nudge to keep Badgwell on track.

After months of give-and-take, the former auto mechanic had decided early in January to seek housing.

Montoya had helped him get food stamps.

Next was applying for general relief, a $221 monthly county payment. Badgwell didn’t show a great deal of motivation. He said he made enough money recycling.

But Montoya reminded him he needed proof that he could pay his share of the rent, even though it could be as low as $8. Under the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Section 8 program, he would pay only 30% of his income in rent, and could also receive a utility offset.

Badgwell said he hadn’t gone to the welfare office yet because he had missed his doctor’s appointment. The rules require him to have a doctor’s clearance before he can apply for general relief.

Dave Curry locks his door to his new apartment in Sunland. After a decade in the riverbed, Curry was ready to try living under a roof.

Montoya said he’d make a doctor’s appointment for the next day and take Badgwell in the van.

“I’ll come back at 10 a.m.,” he said.

Despite his procrastination, Badgwell insisted he was motivated to get an apartment.

“I just want to get a place to live, get back on my feet,” he said. “If I get stable and get a shower and all, I wouldn’t mind going back to work.”

Nothing went as quickly as Montoya hoped. It took three weeks to schedule the doctor’s appointment. Badgwell was approved for general relief in late April. With Montoya’s help, he filled out the 50-page Section 8 application. When the Housing Authority schedules an appointment, Montoya will drive him to the Wilshire Boulevard office to submit it. Two to four weeks after that, he should receive his voucher.

Montoya next stopped beside a thicket and yelled, “Bill.”

“I’ll be out,” Bill replied. “I’m getting ready.”

Bill, who didn’t want his last name used and didn’t want visitors to see his camp, stepped out of the bushes a few minutes later, shaven, coiffed and wearing a freshly washed Hawaiian shirt.

Bill already had his Section 8 voucher, but he was having trouble finding an apartment and time was running out.

His voucher would expire Monday.

“Bill’s heard ‘no’ so many times it’s really hard for him to get out of bed every day,” Montoya said later.

Bill once lived comfortably in a treehouse he built himself. That was torn down in a past cleanup. But until he finds an apartment, Bill said, he will continue to make the wash his home.

“I’m not going to live on the boulevard with a shopping cart,” Bill said. “I don’t want to impose on anyone. I did that.”

::

Montoya regularly visits about 100 homeless people in the northeast Valley.

He estimates that he puts 30,000 miles a year on the van taking clients to appointments at the doctor, the welfare office and the Department of Motor Vehicles, the first stop for many who don’t have identification.

His insight into their lives is shaped by his own experience.

“I grew up with a troubled lifestyle, was in trouble most of my life,” he said. After completing a drug treatment program in Sun Valley, he applied for a job there.

“I felt it was my duty to educate others and help others; that there [are] services available for them, the services that I never got,” Montoya said.

He’s now in his 16th year at LA Family Housing.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

Before the cleanups last fall, Montoya had placed 10 former wash dwellers in LA Family Housing’s new Day Street complex, a 49-unit apartment building in Tujunga with medical and social services on site. Day Street is now fully occupied, crimping Montoya’s housing options.

Still, since the cleanups, Montoya has relocated 24 people from the wash. Thirteen obtained Section 8 vouchers and stay in LA Family Housing’s 250-bed shelter in North Hollywood. They are looking for their own apartments. Four moved in with family or friends, including one young woman who was five months pregnant when she was displaced. She and her baby are living with a friend.

Seven have obtained Section 8 vouchers and have their own apartments. Bill was the seventh. Eight days before his voucher expired, he found an apartment in Sylmar.

One died and one is in jail, leaving seven still in the wash.

The cleanups last fall may have hastened that exodus, but it was already underway by then, said Nathaniel VerGow, who supervises LA Family Housing’s five outreach workers.

The stimulus was a policy shift in Washington and locally that gave the chronically homeless priority for housing vouchers.

After years in which housing vouchers were almost impossible to get, Montoya was allocated a handful for his clients in Tujunga Wash.

Curry was his first taker.

Montoya first encountered Curry on the night of L.A. County’s homeless survey in January 2015. The onetime construction worker had settled into the wash a decade earlier after an illness forced him to stop working and his trailer was foreclosed on.

“He didn’t want anything to do with us,” Montoya said. “He was happy in his tent. There was an old Bowflex. He worked out every day.”

Other outreach workers had promised Curry things but couldn’t deliver. Montoya didn’t have much to offer either.

“At the time it was just shelter,” he said. “He didn’t want shelter.”

Montoya kept trying.

“I would go out weekly, take him water, backpack with supplies, trash bags so he could try to keep his area clean,” he said.

Then the housing vouchers came through.

“I thought he would turn it down and say give it to the next person,” Montoya said. “When he was able to see there was an end to his homelessness and he didn’t have to live in a tent anymore, he jumped on it.”

Curry’s decision set off a chain reaction.

“Not too long after Dave got his voucher, everyone down in the wash wanted a voucher,” Montoya said. “Everybody was just coming out of the woodwork saying, ‘I need help.’”

But Curry’s search didn’t go well.

“Dave was riding his bike all over Sunland-Tujunga,” Montoya said. “He would go from apartment to apartment looking for vacancies and for potential landlords who would take the voucher. He wasn’t having any luck.”

In November, the voucher expired after 240 days. He had to apply again and wait for a new one.

“Toward the end, he almost wanted to give up,” Montoya said.

::

Amy Perkins, LA Family Housing’s rapid re-housing manager, works the phones every day. She and a team of “navigators” make cold calls to landlords — from mom and pops to corporate property managers — with one question: “Do you have a vacancy for a Section 8 voucher?”

Perkins presents it as a “win-win”: guaranteed rent paid on time and support from LA Family Housing if trouble arises.

The state of the rental market makes it a hard sell. With the vacancy rate plunging to 2.7% late last year and rents on the rise, landlords are often able to command more than Section 8 allows.

So her pitch is partly emotional, imploring landlords “to see how happy some of our housing partners are in the community, to see how happy they can be in the placements they have.”

A prime example is Sam Keshish, a used-car dealer who has invested over the years in apartment buildings.

Perkins cold-called Keshish, and they clicked.

“We just kind of developed a phone rapport,” Perkins said.

He took one of her clients and it worked out. Others followed. For Keshish, renting to the homeless became a mission.

“Something needs to be done,” he said. “Somebody needs to step up and do it.”

Perkins called Keshish several times last year about Curry. He had nothing.

Then, this year, a tenant vacated the yellow duplex over Keshish’s Foothill Boulevard dealership. Keshish renovated the apartment and rented it to Curry.

Curry now has space for the possessions he has collected over the years, including two giant speakers, a solar cell and lots of tools.

He has a proper home for his dog, Boo.

And he enjoys his new ease.

“I can go to the bathroom whenever I want,” he said. “And I take a shower every day.”

Twitter: @latdoug

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

ALSO

Scripps College students, faculty protest Madeleine Albright’s selection as commencement speaker

If you registered to vote at the DMV, check again

Elderly Koreatown immigrants keep filling slots at Southland casinos, knowing it’s a gamble

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.