From the Archives: Green Card Marines: Born in Mexico. Jose Garibay was just looking to fit in

- Share via

On this Memorial Day weekend, we take a look back at our 2003 series on Green Card Marines.

The war in Iraq drew attention to the growing number of noncitizens in the U.S. military -- about 37,000. Ten were killed during the war, seven from California. Most were Latino. This is the second of four portraits of Green Card Marines who gave their lives.

The snapshot came straight from the deck of the Navy ship Ponce as it sailed toward Iraq.

He was wearing his Marine fatigues, shiny black boots and the baddest pair of sunglasses. With a pistol in his right hand, he had never looked so menacing.

Toshia Hooven, his girlfriend back home, wondered if it was all a charade.

Only two weeks earlier, on a car ride near Camp Lejeune, Jose Garibay had talked a mile a minute about dying. He had told Hooven he was having nightmares again about the fighting to come in Iraq. He had promised he'd keep his head down but told her that, if a bullet found him, he wanted his casket open.

She knew that all his life -- in a tiny village in Mexico, in his home in Costa Mesa and in the Marine camp in North Carolina where he was known as Gummi Bear -- he had taken on different personas as a way to get by.

Over the years, he had hidden his Mexican heritage, separating himself from his family to find his way in America. Like a chameleon, he had melted into the landscape of the other side.

We are freedom's answer to fear. We do not bargain with terror. We stalk it, corner it, take aim and kill it.

— Jose Garibay

Now, on the eve of battle, 22-year-old Jose had steeled himself with a new identity. "We are freedom's answer to fear," he wrote to Hooven. "We do not bargain with terror. We stalk it, corner it, take aim and kill it."

It was a voice she did not recognize.

On the fifth day of the war, he was in Nasiriyah and encountered a group of Iraqis pretending to be something they weren't. Caught by surprise in an ambush by enemy soldiers making gestures of surrender, Jose died with six other Marines.

Several weeks ago, at his funeral in Costa Mesa, people from the different parts of his life honored him: a surfer, an Internet friend, a high school football teammate, his teenage sister with two children, his mother who works as a hospital maid and the postal worker who took him in when he left home at 16.

Among the mourners was Toshia Hooven's mother, the manager of a KFC in North Carolina. The Jose she knew, she said, was a boy named Joe who had fallen in love with her daughter, a heavyset girl with bleached hair and hard luck and a 15-month-old son by another man.

Joe liked nothing more than eating chicken at Ruby Tuesday's and shopping at Wal-Mart, Debbie Caudill said. He never uttered a word of Spanish or hungered for the taste of a tortilla. He got so good at fitting in that her daughter, in eulogizing him, said he had made her forget that he was Mexican.

"I think he felt he had to be whatever everyone else wanted him to be," Caudill said.

There is no one place to find Jose Angel Garibay. He left a footprint in Mexico, where he was born, and a footprint in Iraq, where he died, and a footprint in Costa Mesa, where he grew up.

It was in Costa Mesa, just a few miles from the beach, the malls and Disneyland, where he began shedding the old Jose and creating a new Joe. He was not unlike other immigrants who have chosen to embrace American culture with a fervency that leaves little room for the past. But by the time he was done reinventing himself, he blended in so thoroughly that some of his closest friends were people who felt contempt for Mexicans, even as they regarded Jose as the exception.

His death at such a young age prevented him from discovering what so many immigrants eventually do: that there is room in one man's life for two countries, two languages, two cultures.

As he prepared to walk onto the battlefields of Iraq, he seemed to be struggling with the price of erasing his roots. In a last batch of letters home, it is possible to glimpse a young man on the brink of one of life's most defining moments, trying to puzzle out what was genuine in his life. The young soldier, forever an outsider, would cross a last border not knowing who he was, afraid of dying before he could find out.

Dividing Lines

No matter where he stood, the lines never vanished: dividing Mexico from America, Orange County's rich from poor, white kids from brown kids. The trick was getting over to the other side. It became the game of his life.

He was only a few months old when his mother, Simona Garibay, standing on the Mexican side of the border, placed him in the arms of an Orange County couple and pretended to be their nanny. The son she called Angel crossed into the United States without a fuss, as if he belonged to them.

Documents or not, he had a claim to this side. It was during a stay with her boyfriend in Costa Mesa that Simona Garibay had conceived him a year earlier. Only after returning to Jalisco did she learn she was pregnant. Her boy was born in a free clinic on the grounds of an elementary school in the tiny town of Los Tecomates.

The decision to migrate north split the family in two, she and Jose on one side and her three grown children by another man on the other. Costa Mesa did offer the chance for reunion with her two brothers, Urbano and Melquiades Garibay, both gardeners who had settled there. Blending into the city's west side was easy, with its taco shops and Latino five-and-dimes and apartments full of newcomers.

She took Jose to get his shots, she said, "and then I just joined the flow of life here."

She tried to make a go of it with the landscaper who had fathered Jose. They moved into a trailer but stayed together less than a year. Jose Angel never took his father's name.

Their status as illegal aliens prevented her from pursuing child-support payments, Simona said. She moved into the house of her brother, Melquiades, earning her keep by caring for his children. Jose grew up so close to one cousin that he considered the boy a brother. He loved his aunt's ceviche, the tangy fish cocktail that she served on a fried tortilla.

Simona Garibay doesn't recall much from those years. Poverty flattened out their lives, gave them a mundane sameness. She said she made sure her son got plenty of fresh fruit -- grapes, watermelon and apples -- and on Sundays they would stroll to the park and splurge on pizza and games at Chuck E. Cheese's. If she had a few extra dollars, she would press the money into his hands. Go out and buy a burger or candy, she would tell him. Instead, he would stash away the money for clothes and shoes, caring how he looked, even as a little boy.

His kindergarten teacher, Martha Blair, still remembers the high-energy kid. He had a hard time sitting still. Coming from a house where no English was spoken, Jose developed more slowly than the other kids and had to repeat the grade.

"He was a very active little boy. He was one of those little guys you had to keep your eyes on," she said. "From the beginning, he liked the physical stuff."

He became fascinated with toy soldiers and GI Joe dolls. He could sit in front of the TV for hours, watching football and professional wrestling. He loved model cars and airplanes.

His mother got involved with one man and then a second, giving birth to a girl named Crystal and a boy named Gabriel.

Jose, his mother and his siblings shared a broken-down, two-bedroom, rented house. A pile of junked appliances littered the backyard. Jose slept on a couch in the living room. He had for himself only a closet, where he kept his clothes, old toys and books.

He grew to be the man of the house, taking special pride in watching over Crystal, who was four years younger. He had a hawk eye. At home, the moment a boy came around, he would shove his sister indoors.

"He'd get jealous and say, 'Get in the house! Don't come out!' " Crystal said. He hated it when his friends teased him about his sister's many admirers.

He could play the mother role too. When Simona took a job as a housekeeper at the nearby College Hospital, it was Jose who held down the home front, baking cakes for birthdays and roasting a turkey on Thanksgiving. She would come home from work and he would tell her not to worry about any household chores. Rest, Mami, he'd say in Spanish.

"He was very good to me. He never talked to me in English because he said he wanted me to speak only as I really spoke," Simona said. "If I ever scolded Angel, he'd never talk back."

In later years, Jose Garibay would tell Hooven another story, one that suggested he wanted nothing more than to be a kid. The role of fending for himself and his siblings wasn't always his choice.

One day, she recounted his saying, there was no food in the house and his mother promised to go to the store. She left and hours passed without a word. He said he got so hungry that he climbed to a shelf and brought down his piggy bank. He shook out what coins he had saved and stuffed them into his pocket. He then walked to the store and bought a loaf of bread. His mother came home late that night, but she had no groceries in her arms.

Life in Transition

Jose began to separate himself emotionally from his family in his early teens, his mother recalled. He had acquired the status of a legal resident, and she decided to seek child support payments from his father. The father denied that Jose was his son, the Garibays said, and wouldn't pay a dime without a blood test.

The test confirmed Jose's paternity, they said, and the father agreed to pay $150 a month.

The wound of rejection never left Jose. On Father's Day, he would make a card at school for his uncle Urbano, who didn't have a son of his own. "Ever since that day, he'd say, 'I don't have a father, Mami,' " his mother recalled. "He'd laugh, but with pain."

He found himself surrounded by skaters and surfers, jocks, cheerleaders and preppies at Newport Harbor High School. He went out for football, even though he was only 5 foot 7 and 160 pounds. He was never very good at it, but he worked hard -- lifting weights and running extra wind sprints.

"He did the most with what he had, and what he had was next to nothing," said Mike Bargas, his coach. "He liked the discipline here. He liked the structure. He craved the regimen."

Bargas noticed that Jose never spoke Spanish. Some students went to school in Mexican soccer team shirts or other symbols of their native land. Not Jose. Other Mexican American students, who had been born in California or had lived here most of their lives, took on the baggy clothes and exaggerated gestures of hip-hop. Jose dabbled for a time with a street gang but decided in the end that he wanted no part. He worked part time at a discount clothing store.

He befriended teammate Aaron Maher, a surfer with spiked hair. After school, they hung out at pool halls and the Wedge, a famous surf spot in Newport Beach. Jose soon became a regular visitor at the Mahers' spacious condo. Before long, he was spending weekend nights there.

"He was at a crossroads," said Richard Maher, a single father who works as a communications manager for the U.S. Postal Service. "The one path could be in a gang or drugs. The other could be to graduate high school, follow his dreams and get what he wanted -- a piece of the American pie."

At the end of his sophomore year, Jose left home and moved in with the Mahers. He never talked about his family and rejected offers of Mexican food. He craved hot dogs, steak and potatoes. He chipped in by doing the laundry and cooking whole fish and other dishes he learned to prepare in his home economics class.

To friends outside the Maher house, he would refer to Richard Maher as "Dad" and Aaron as "a brother." Inside the house, though, no matter how close they became, he insisted on calling Richard Maher "Mr. Maher."

Simona Garibay said she never lost contact with her son, but it seemed important for him to keep a wall between worlds. "He only came to visit me," she said.

Jose transferred to nearby Costa Mesa High his junior year, in September 1999, telling friends that the move would increase his playing time on the football field. He never tried out for the team, though. It was enough that he now had a girlfriend, Crystal Capen, a cheerleader at Costa Mesa High.

Crystal's mother, Marilynn Capen, had married and divorced twice and raised five children. The Capens' Costa Mesa house doubled as a day-care center for a dozen preschoolers. Capen had watched the west side of town turn Latino and couldn't help but wonder if the immigrants -- who "came like bees" -- were changing her city for the worse.

In her eyes, Jose was different. "He didn't act Mexican," she said. Whenever one of the Spanish-speaking day care workers tried to talk to him in his native tongue, Jose would get angry and answer in English. "He didn't want to offend us with Spanish," Marilynn Capen said.

On trips to Arizona and Las Vegas with her daughters, Capen took Jose along. He became a walking tour guide for Las Vegas, researching facts about the city on the Internet. He began talking about a new calling. He wanted to be a cop and work the casino beat. He grew so close to the Capens that, at night, when he didn't feel like returning to the Mahers' condo, Jose made a bed for himself in the room that doubled as the day care area.

Joining the Marines Family

It was as Jose was distancing himself further from his real family that the military bug seems to have bitten. He began confiding to Chuck Schubert, a television studio teacher at Costa Mesa High, about wanting to join the service. Schubert, a colonel in the Army Reserve, taught a rapt Jose everything the teacher knew about M-16 rifles and the munitions system on a Black Hawk helicopter.

Schubert told Jose he might do better in the Army, where he could advance faster and earn his spurs as a military police officer. But Jose wanted to be a Marine, the toughest and the best.

In the spring of his senior year, he returned to Newport Harbor High to graduate. He had intended to ask Crystal to the prom, but he didn't have the money. When Richard Maher asked Jose about his plans, he was sheepish. Maher took it upon himself to push the matter and lent Jose a tuxedo. Crystal's mom rented a limo and slipped Jose $50. That night, Jose and Crystal went to the Outback Steakhouse and then to the Fox Country Club in the Anaheim Hills.

They began to drift apart as boyfriend and girlfriend, but they still spent their weekends jogging and hanging out with local Marines. After graduation, they both enlisted and headed off to boot camp in San Diego. Jose stuck with the Marines; Crystal chose the Navy. A year after their breakup, he would continue to refer to Marilynn Capen as "my mom."

Jose returned home to the small brown house in Costa Mesa to say goodbye to his real mother. He was wearing his Marine uniform, and they posed together for a photo in the frontyard. No matter how distant their relationship had become, he decided to send her a good chunk of his $1,100-a-month military salary. The money almost always came with instructions on how to spend it: Buy new sheets for the family, Mami; buy a Nintendo for brother Gabriel.

In January of 2001, Jose was sent to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. Before arriving, he posted a personal ad on Yahoo! with a picture of himself in uniform. He was looking for new friends, he said, and he soon got a response from the daughter of a Presbyterian minister who lived an hour's drive from the base.

Calista Hofland was only 15, but Jose confided in her. He told her he was having a hard time reconciling a military culture that demanded such discipline by day and allowed such debauchery by night. While his fellow Marines hopped from strip club to strip club in nearby Jacksonville, he rarely left the base. He ran, lifted weights, burned CDs on a computer and rented scary movies.

A few months after their online meeting, Calista visited Camp Lejeune. But she ended up meeting and falling in love with another Marine, Kevin Vitale. They married and took in Jose as family. "He was trying to reach out and find someone he could connect to," she said. "He was so unconnected to his family. He grabbed onto me and Kevin. He wanted roots."

Jose had no one to take to the annual Marine ball, and Calista Vitale agreed to be his date. From afar, he looked sharp in his formal uniform. On closer inspection, he had put the removable buttons on backward. Calista didn't want to hurt his feelings so she said nothing. They had barely reached the dance floor when someone pointed out the mistake. He ran to the bathroom embarrassed and switched the buttons around.

Before he shipped off to Japan, Vitale gave him a new nickname. He had been joking that he was as "scary as a bear." You're a bear, all right, she told him. A soft and chewy Gummi Bear.

In Okinawa, he played on the Marine rugby team. He was no better at rugby than he was at football but that didn't matter to Jesse McDonnell, the Charlie Company squad leader. Jose enjoyed the friendships and the beer drinking and the Marine songs they sang after each game, McDonnell said.

By Easter 2002, Jose was back at Camp Lejeune clutching a four-day pass with nowhere to go. Someone in his dorm was headed home to Kentucky, and Jose looked at the map and put his finger on Knoxville. Drop me off there, he said.

His first stop was the local university, where he strutted around in his uniform in hopes of impressing a coed. Mandy Bergey couldn't help but notice him sitting in an empty library.

"He didn't look like he belonged," she said. "I thought I would help him out." She invited him to Easter service at the Calvary Baptist Church and then took him to the home of Lisa Humphreys, a mother of four who hosted students at her house and shared her faith.

Jose would later tell friends that he felt an instant connection with Humphreys and her children. Long after that weekend, they exchanged letters and care packages.

"We felt that it was not a random act that he came to us," Humphreys said. "He seemed to care a lot about us too."

It was during his last three months at Camp Lejeune, in the fall of 2002, that the Internet delivered a new friend.

A Home for the Holidays

Toshia Hooven was a 20-year-old single mom with a slight drawl who had selected Jose from hundreds of Marine photos posted on Yahoo! Hooven had moved from the hills of North Carolina to a small town near the military base. She shared an apartment with her baby son, Nathan, and her mother, Debbie Caudill, who had taken a new job managing a local KFC.

"Hey, do I know you?" Jose messaged back. That led to a four-hour instant messaging session followed by a five-hour phone conversation. He was just about the most polite young man she had ever talked to. When she confided to him the trials of being a single mother, he talked about the disappointments in his own family.

"If you didn't know him and talked to him for an hour, you'd think he had lived with Richard and Aaron Maher his whole life. He even told everyone on base that he had been adopted by them."

After his aimless Easter holiday, Jose was determined to have a place to go for Thanksgiving. He had written Humphreys in Knoxville and asked if he might spend the holiday at her house. But after meeting Hooven and her mother -- and securing a Thanksgiving invitation to their place -- he changed his mind.

Hooven's mother told him to name a special dish he would like. He asked for carrots and peas. Garibay polished off dinner and stayed for four days. By that time, it hardly mattered that the nice young man with the caramel complexion and dark eyes turned out to be Mexican. He had no accent. He spoke Spanish only during the few times he called home to his mother, and those conversations were usually brief.

"Where I come from, the races don't mix," Hooven said. "But it never went through my mind that he was Mexican."

He stayed at Hooven's apartment every weekend after that. They never ventured far -- shopping at the local chain stores and eating at the local chain restaurants. Garibay would dart into the toy department and buy a GI Joe and a toy Humvee -- for himself. He picked up dozens of true-crime books and was a sucker for any DVD with a military theme.

He showered gifts on Hooven and her son, Nathan, as well. The boy lighted up every time he walked into the room. One day, just weeks into their relationship, Jose bowed his head in an embarrassed manner and declared his love for the two of them. He referred to himself as Nathan's "daddy" and talked about the day they would move to Las Vegas, where he would be a cop.

As his deployment date drew near, he began waking up in the middle of the night, heart pounding. He told Hooven he kept having the same nightmare: He was in combat and someone was chasing him.

"At first, he told me he would take a bullet for one of his fellow Marines because they had family to come back to. After we got closer, he said he wasn't going to take any chances because now he had Nathan and me." They said their goodbyes on Jan. 7. He boarded the Ponce in Virginia and, four days later, headed out to sea.

When he learned she might be pregnant -- a false alarm, it turned out -- he seemed to welcome the news. "I am worried, not that you are pregnant," he said, but that he would not live to be there. "Or, if I make it back, will I be a good dad?"

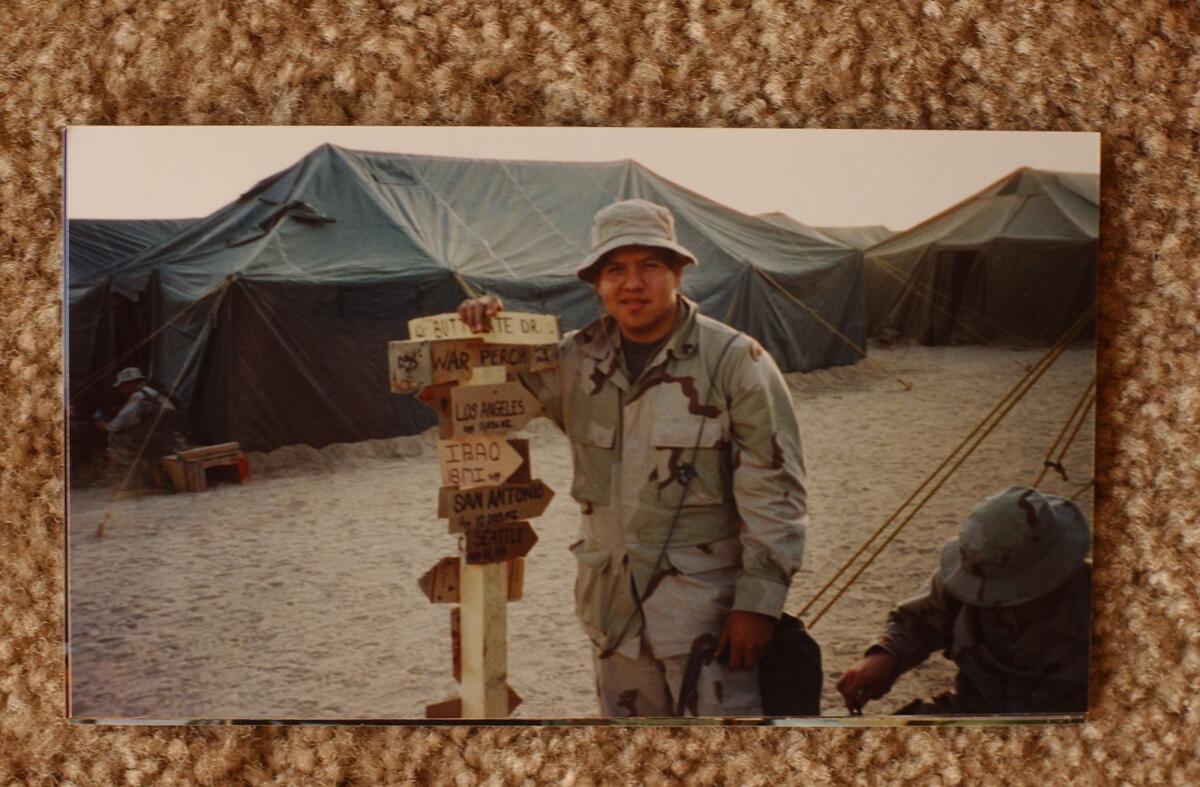

On the eve of the march toward Nasiriyah, days before he was killed, Jose sat in a 20-man tent in the desert and wrote a final batch of letters.

In one letter, he asked a friend to send him Snickers bars. In another, he told Hooven that his nightmares had returned but promised he would keep his head down. He was going to come home alive and treat her to a chicken and rib dinner at Applebee's.

"Expect 100 kisses from me when I get back. I'll hug you to death." He signed both letters Joe.

In a last letter to his mother, he asked for tamarindo candy and a tape of Vicente Fernandez. The legendary Mexican cowboy singer was just about the furthest thing from his favorite rock artist, Marilyn Manson.

"Cuando regrese vamos a celebrar con carne, ceviche y cerveza," the letter to his mother ends.

Whenever I return, we will celebrate with meat, ceviche and beer.

He signed it Jose.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.