This South L.A. corner is no place for ex-inmates to reenter society, critics say

- Share via

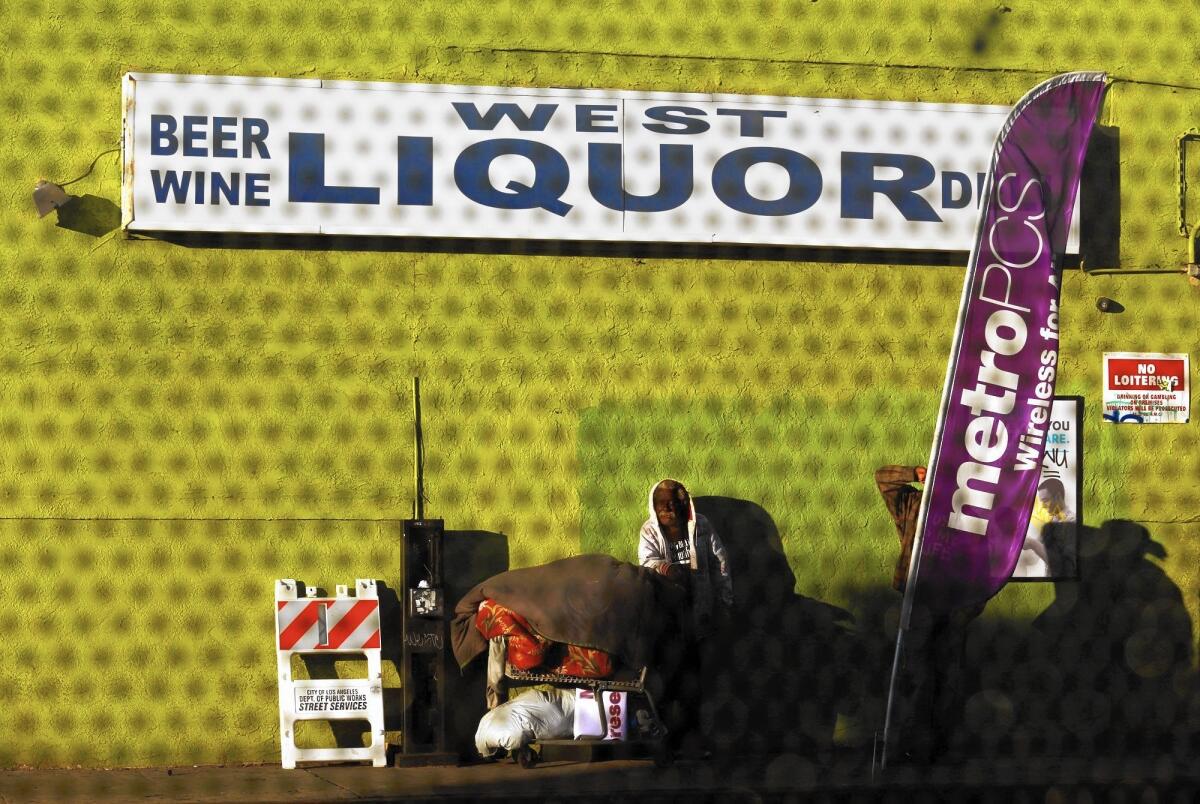

The South Los Angeles intersection of Vernon and Western avenues is anchored by a liquor store and a boarded-up mini-mall. Murders have roiled the area over the last year — including a recent drive-by shooting before noon. Neighbors complain that prostitutes and drug dealers linger nearby.

At a recent hearing at City Hall, community members and activists argued it was no place for people trying to shake off a criminal past. They denounced the plans of a company that wants to open a Vernon Avenue residential facility that would provide services to scores of former inmates.

“If you want to put parolees in an environment where there’s drugs, prostitution, gang war … all the vices that will send them back to jail, I think this is the location,” said Karim Zaman, a businessman who said he had heard fatal gunshots across the street from his Vernon Avenue office.

But others argue that the facility is exactly what former inmates need.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

“The people who are being released from prison are coming to our community anyway,” said Leonard Delpit, an area representative on the Empowerment Congress Central Area Neighborhood Development Council, which backed the plan. He praised the company, Geo Reentry Services, for being “willing to empower these people.”

After a contentious hearing this month, a Los Angeles City Council committee voted against the Vernon Avenue proposal, sending it to the entire council for a final decision. A report by council staff said the facility “does not promote a strong and compatible commercial sector,” was not compatible with community plans and would worsen neighborhood blight.

“Any reasonable person that stands at the corner of Vernon and Western for even five minutes knows that this makes no sense,” Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson said at the hearing.

His spokeswoman Chanelle Brown later said that the councilman also had concerns about former inmates being negatively affected by illegal activity in the neighborhood.

Geo counters that the neighborhood is no worse than many other areas that successfully host such programs and has a number of advantages over more isolated sites, including easy access to public transportation. It says it wants to provide an array of services to men exiting prison, including job training, anger management, GED preparation and substance abuse treatment.

“Without reentry programs, these folks are going to be facing those temptations every day in their life,” said Rachel Kienzler, regional director of business development for the reentry services provider. “Our job is to prepare them to be able to cope with that.”

Company representatives point out that the Vernon Avenue building, now vacant, had been approved and used for similar programs in the past. Former inmates wouldn’t be able to loiter in the neighborhood, Kienzler said. Residents would be able to leave only for previously approved reasons, such as going to work or visiting family, Geo officials said, and the company would check on them randomly.

Last year, planning officials and a city commission supported the plan for a facility housing up to 140 men, deeming it suitable for the area. The local neighborhood council backed it too, telling planning officials in a letter that the new facility would provide “vital programs to help men get their lives back on track.”

But the proposal troubled some activists and other community members, who urged city lawmakers to reject it. Community organizer Cheryl Branch argued that the area was stricken with violent crime and would not help people leaving prison to thrive. She said the area should instead have “viable, robust commercial uses along its valuable transit corridors.”

Experts said they knew of little research on whether the crime rate in a neighborhood affects the success or failure of programs for people transitioning out of prison. Many said that other factors, such as whether they could access jobs, were much more crucial.

Ultimately, however, “I think a lot of what will determine the success of the halfway house is how it’s operated,” said Stefan LoBuglio, director of corrections and reentry for the Council of State Governments Justice Center. “Communities have legitimate concerns to ask, ‘Will this be an asset to my community?’”

Much of the debate over the Vernon Avenue facility has swirled around Geo and its track record. Geo Reentry Services is part of Geo Group, which identifies itself as the biggest corporation providing correctional and reentry services worldwide.

It has repeatedly faced lawsuits and allegations of mistreatment at other facilities. For instance, the Department of Justice said it found “egregious and dangerous practices” at one of its Mississippi correctional facilities four years ago, including a pattern of excessive force used against youth.

“These people have been profiting off of our misery,” said Susan Burton, executive director of A New Way of Life, which assists formerly incarcerated women.

Company officials said that most of the troubling incidents in the report had happened either before Geo assumed management of the Mississippi facility or in the first few months afterward. The company also said it had made “significant improvements.” However, the federal report stated that “key personnel, policies and training … did not change substantially” after the reentry services provider merged with its previous operator.

Closer to Los Angeles, the company has also faced criticism over an immigrant detention center that it runs in Adelanto. The ACLU of Southern California and several immigrant rights groups wrote federal officials last year, raising concerns that Geo “consistently has denied or delayed necessary medical and mental health treatment to Adelanto detainees.”

In response, Geo vice president of corporate relations Pablo Paez said the facility provided “comprehensive, around-the-clock medical services pursuant to strict contractual requirements.” The company also touts high scores for Adelanto and other facilities from the American Correctional Assn.

Angela Moore, whose late father, Roy Evans, headed the previously operating Bridge Back program at the Vernon Avenue site, said he had purposefully sought out Geo after his own program dissolved. The Evans family still owns the building, which is slated to be sold to Geo if it gets city permission for the facility.

“He didn’t just enter lightly into this,” Moore said. “He chose them to carry out his legacy.”

Branch, who faced public accusations that she was trying to get the building for herself, denied that and said her reasons for opposing Geo were simple.

“We do not want private prison operators in our neighborhood, even if they rebrand themselves as reentry programs,” Branch said.

The council is scheduled to take up the proposal Tuesday.

Twitter: @LATimesEmily

ALSO

The problem with your lottery tickets and school funding

He brokered deals for an empire of California charter schools -- and now faces a felony charge

Orange County jail escapee fled the law before, fleeing to Iran

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.