Battling treacherous office chairs and aching backs, aging cops and firefighters miss years of work and collect twice the pay

- Share via

When Capt. Tia Morris turned 50, after about three decades in the Los Angeles Police Department, she became eligible to retire with nearly 90% of her salary.

But like many cops and firefighters in her position, the decision to keep working was a financial no-brainer, thanks to a program that allowed her to nearly double her pay by keeping her salary while also collecting her pension.

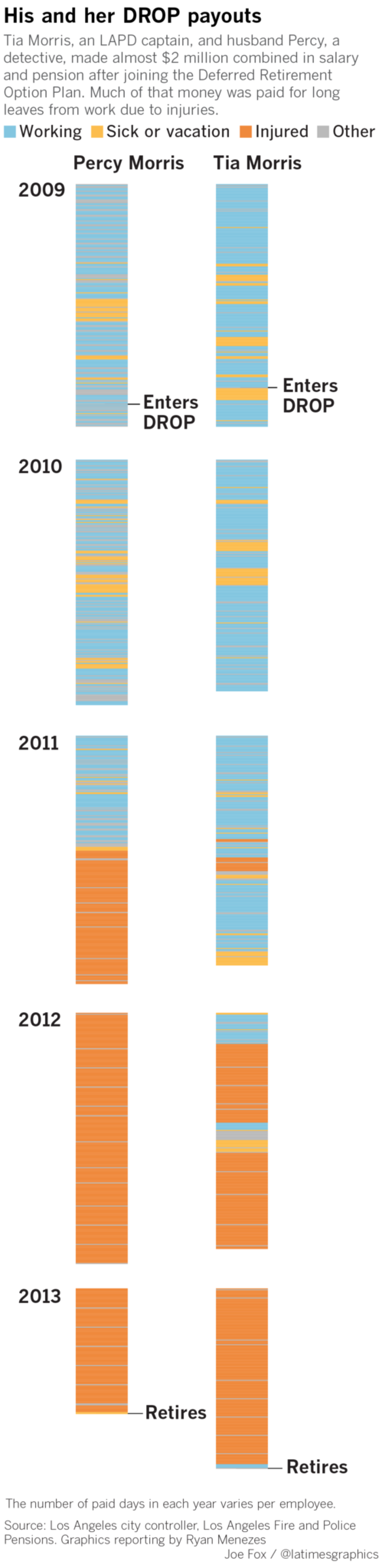

A month after Morris entered the program, her husband, a detective, joined too. Their combined income for four years in the Deferred Retirement Option Plan was just shy of $2 million, city payroll records show.

But the city didn’t benefit much from the Morrises’ experience: They both filed claims for carpal tunnel syndrome and other cumulative ailments about halfway through the program. She spent nearly two years on disability and sick leave; he missed more than two years, according to a Times analysis of city payroll data.

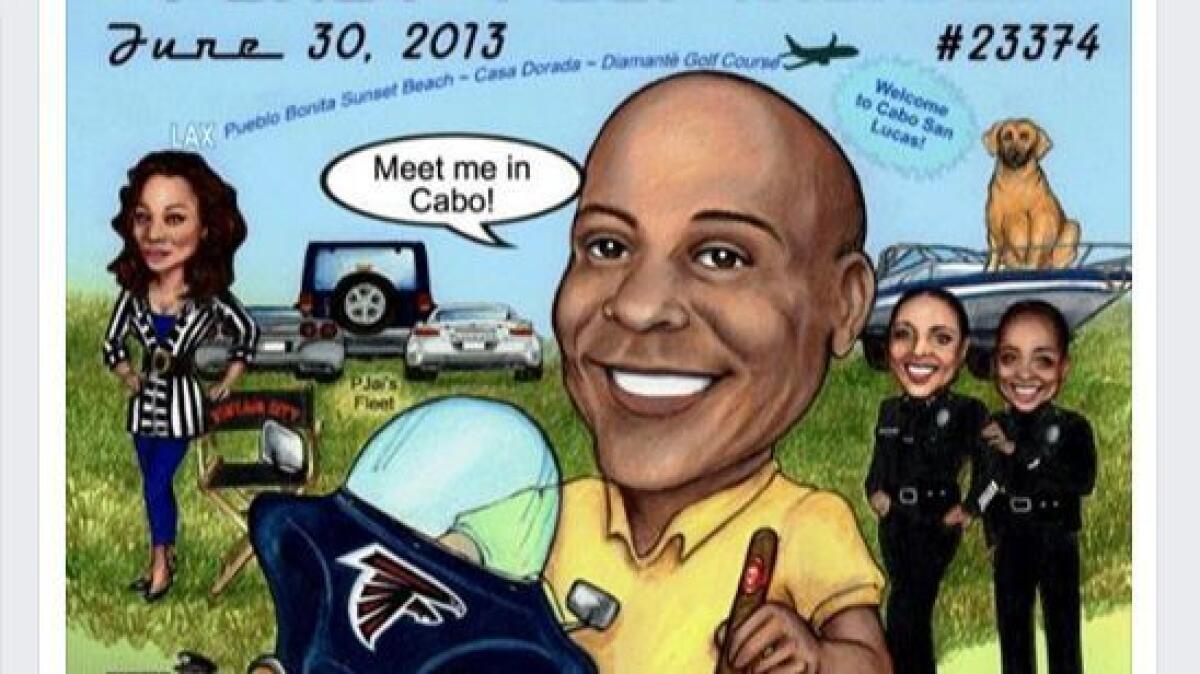

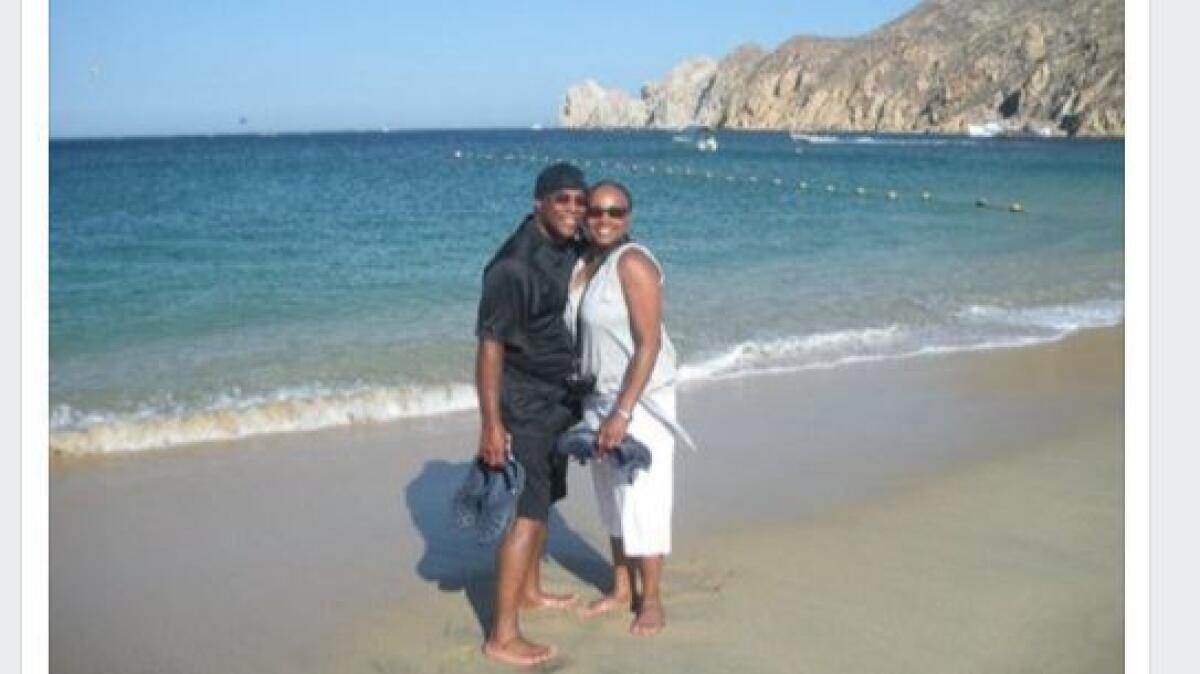

The couple spent at least some of their paid time off recovering at their condo in Cabo San Lucas and starting a family theater production company with their daughter, according to Tia Morris’ Facebook posts and her self-published autobiography. They declined to comment for this story.

The Morrises are far from alone. In fact, they’re among hundreds of Los Angeles police and firefighters who have turned the DROP program — which has doled out more than $1.6 billion in extra pension payments since its inception in 2002 — into an extended leave at nearly twice the pay, a Times investigation has found.

Former Police Capt. Daryl Russell, who collected $1.5 million over five years in the program, missed nearly three of those years because of pain from a bad knee, carpal tunnel and multiple injuries he claimed he suffered after falling out of an office chair.

“It was defective,” Russell said of the chair during a recent interview. “I believe the screws underneath came out.”

Former firefighter Thomas Futterer, an avid runner who lives in Long Beach, hurt a knee “misstepping off the fire truck,” three weeks after entering DROP, according to city records. The injury kept him off the job for almost a full year.

Less than two months after the knee injury, a Tom Futterer from Long Beach crossed the finish line of a half-marathon in Portland, Ore., in a brisk 2:05:23, according to race results posted online. Only one Tom Futterer lives in Long Beach, according to public records.

Futterer did not respond to repeated requests for comment. His attorneys, Roger Cognata and Robert Sherwin, refused to confirm whether Futterer had run the half-marathon in Oregon.

Big money, questionable results

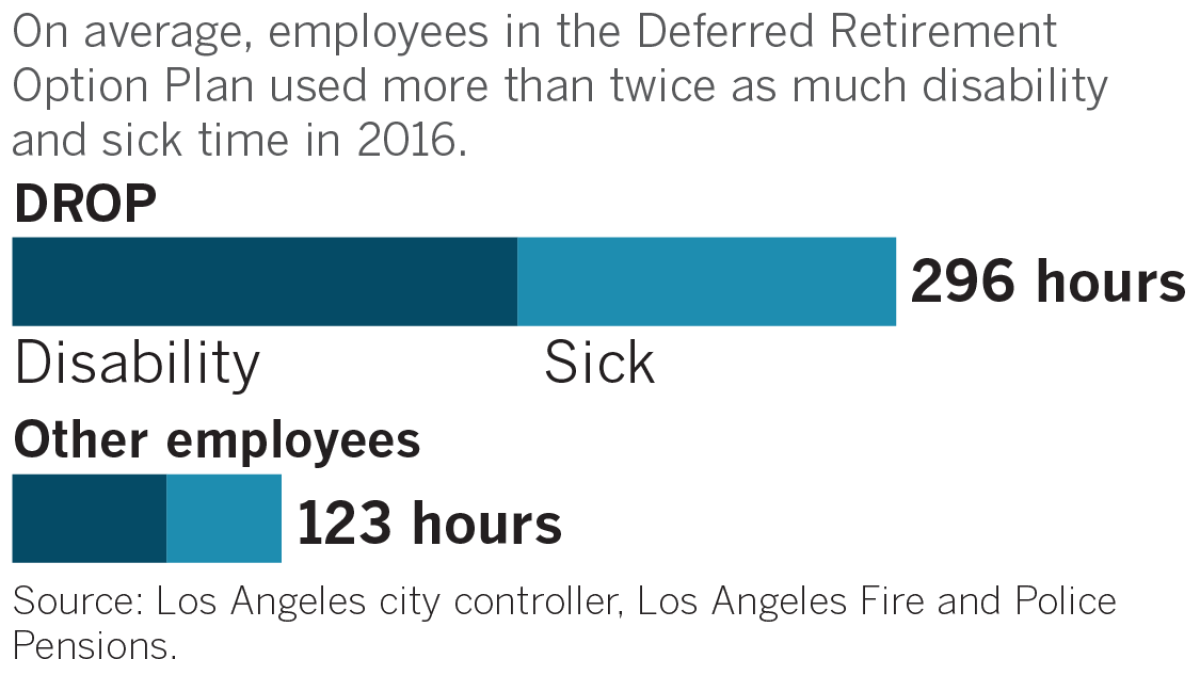

City officials say they have never studied the amount of disability and sick time taken by DROP participants, but a Times review of thousands of pages of workers’ compensation files and tens of millions of computerized payroll and pension records from July 2008 to July 2017 found:

• Police and firefighters in the DROP program were nearly twice as likely to miss work for injuries, illness or paid leave.

• Those taking disability leave while in DROP missed a combined 2.4 million hours of work for leaves and sick time and were paid more than $220 million for the time off.

• More than a third (36%) of police officers who entered the program went out on injury leave. At the fire department, it was 70%.

• The average time off for those who took injury leaves was nearly 10 months. At least 370 missed more than a year.

• In addition to the salary and pension payments, leaves taken by DROP participants create a third cost for taxpayers: The Fire Department pays overtime to fill their shifts; the Police Department requires other officers to cover their work.

The idea of allowing retirement-age public employees to collect their pensions while working and receiving paychecks originated more than three decades ago in tiny East Baton Rouge, La.

But it wasn’t envisioned as a program to retain experienced employees, said Jeffrey Yates, the city’s retirement administrator. In fact, the goal was the opposite: to discourage older employees from staying so long that they limited upward mobility for younger workers. And it had a two-year time limit.

Since then, versions of the program have been adopted by dozens of states, counties and cities across the country. The details vary — some have short terms to encourage early retirement, others have long terms to retain experience — but the central appeal for employees is constant: two large checks instead of one.

Allowing employees to take long stretches of paid time off while in DROP runs counter to Los Angeles city leaders’ stated rationale for the program, which was to keep experienced and savvy veterans in firehouses and police precincts serving the public and mentoring new recruits.

‘That was a mistake’

The Los Angeles police union proposed the program to former Mayor Richard Riordan in 2000 when senior officers were retiring early or leaving for other jobs in the wake of the Rampart scandal, which exposed widespread corruption within the department.

Voters approved a 2001 ballot measure that promised “no additional cost to the city” to create the program. Since then, roughly 5,000 of the city’s public safety officers have joined DROP, which allows them to collect their salary and pension simultaneously for up to five years at the end of their careers.

In 2016, officers exiting the program had been paid an average of $434,000 in extra pension payments, according to a Times analysis of Los Angeles Police and Fire Pension fund data.

Asked about the program last year, Riordan said: “Oh, yeah, that was a mistake.”

Riordan said he supported DROP to appease the police union during a tumultuous period in city politics, but that it had been dogged by rumors of abuse from the beginning.

Told that nearly half of all DROP participants who entered the program had subsequently gone out on disability leaves, Riordan, now 87, said he remembered hearing the number was even higher. “Either way, it’s total fraud.”

The Times reviewed thousands of pages of workers’ compensation records for police and firefighters who took disability leaves while in DROP. None of the injuries described in those files was the immediate result of intense action, such as running into a burning building or confronting a combative suspect.

Instead, the injuries claimed by program participants, who must be 50 years old with 25 years of experience, were for ailments that afflict aging bodies regardless of profession: cumulative trauma to knees and backs, high blood pressure, cancer and carpal tunnel syndrome — all of which, under state law, are presumed to be job-related for police and firefighters.

City officials acknowledged that taking long leaves at the end of careers to treat nagging injuries is an ingrained part of the culture.

“Historically, police and firefighters have always waited until they’re close to retirement to go out and fix all their aches and pains,” said Maritta Aspen, who is in charge of employee relations for the city administrative officer.

Asked whether it makes sense to pay them double while they take time off to do that, Aspen said, “Obviously, that wasn’t the intent. It was to have them working for a longer period of time, to extend their careers.”

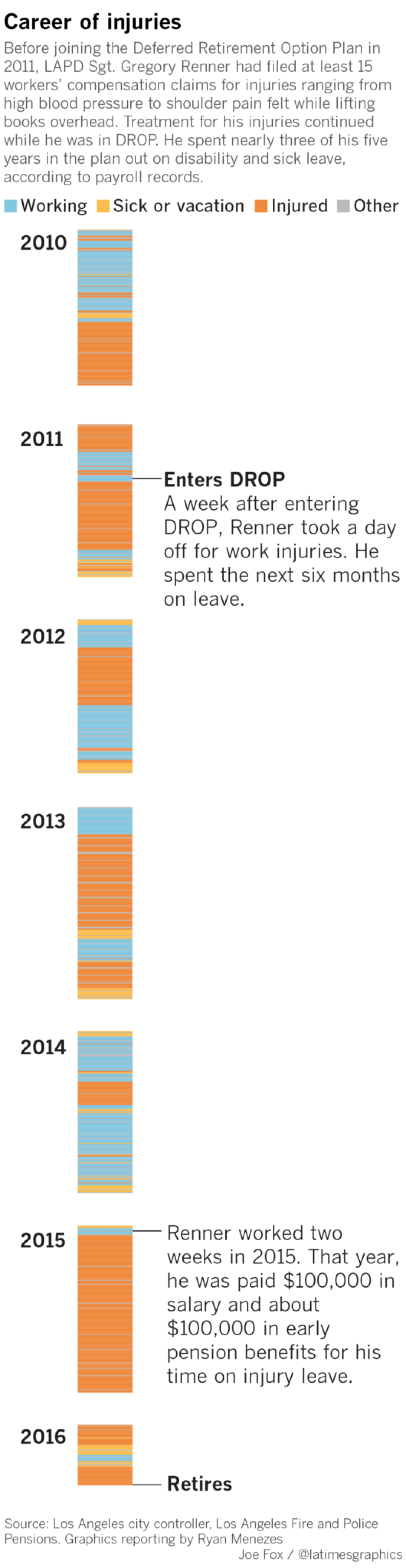

Former LAPD Sgt. Gregory Renner was paid almost $1.2 million for his five years in DROP. He missed nearly three of those years on disability and sick leave, payroll records show.

Before Renner entered the program in 2011, he had filed at least 15 workers’ compensation claims for injuries including sore knees, wrists and shoulders, high blood pressure, ulcers, a tumor on his bladder, a hernia and a sharp pain he felt in his left shoulder while lifting books overhead.

Renner said his most painful injury occurred during the 1992 riots when a looter threw a video cassette recorder at him, damaging his elbow. He left the field for a desk job in the mid-90s.

Renner’s injuries have cost the city more than $2 million, city records show.

City officials concede that, aside from making sure an employee meets the age and experience requirements, there is no screening of applicants before accepting them into DROP. And once in the program, there is no mechanism to suspend the extra pension payments no matter how long an employee is unable to work.

“When you come in to sign up for DROP, you have to be on active duty, but then the following day you could trip on a ladder, or whatever it might be, and you could be out until the day you exit,” said Raymond Ciranna, general manager of Los Angeles Fire and Police Pensions, which administers the program.

Difficult to change the rules

Senior Los Angeles Fire Department officials — many of whom are in DROP and stand to collect high six-figure payments from the program — declined to comment for this story.

Assistant Police Chief Jorge Villegas, who joined DROP in 2015 and could walk away with nearly $900,000 in extra pension pay at the end, said any change to the rules would require careful deliberation.

“I think that’s something that has to be negotiated with the various unions,” Villegas said. Asked whether the department should be able to prevent employees with poor attendance because of a long history of injury claims from entering the program, Villegas said, “I think we cannot be discriminatory.”

Villegas has not taken any time off for injuries since joining DROP, city records show.

When most Los Angeles taxpayers reach the standard retirement age, 65, they face a stark choice: keep working and collecting their paychecks or quit and start collecting Social Security, which replaces only a small fraction of annual wages for most people.

When city firefighters or police officers reach their retirement age, 50, the choices are far better. They can keep working for a paycheck, they can retire with up to 90% of their salary in pension and city-subsidized health insurance for life, or they can enter DROP. For many, the choice is easy.

If they choose DROP, they keep working and collecting their paychecks for up to five years while their pension checks are deposited into a special account. They don’t get any more pension credit for the time they spend in DROP — pensions typically increase with every extra year worked — but the city guarantees 5% interest on the money in the account. The city also adds annual cost-of-living raises to the pension checks to make sure they keep pace with inflation.

When the employee quits working and exits the DROP program, the paychecks stop, the pension continues and the money in the account is transferred to the employee.

Of the 2,583 cops and firefighters who entered the program between July 1, 2008, and July 1, 2017, 860 have collected more than $1 million in combined salary and pension payments during their tenure in DROP, The Times found. Thirty-one have collected more than $2 million.

Because pension payments that begin early are usually a bit smaller, union leaders argue the cost to the employer is offset over time. But in recent years, a growing number of jurisdictions have abandoned or drastically scaled back DROP programs because the math doesn’t work.

Other cities dropping DROP

Instead of saving money, or remaining “cost-neutral,” the programs lead to ballooning pension costs and accusations that employees are simply double-dipping.

In Alabama, a statewide DROP was discontinued in 2011 after reports that some of the top beneficiaries were high-level administrators, lobbyists and football coaches.

San Diego closed its DROP to new employees in 2005 after officials decided it was ineffective and too costly.

Despite the backlash against the cost of the programs, there has been little public scrutiny of employees taking long stretches of paid injury time while also collecting dual checks.

The Times contacted officials and reviewed policies in roughly a dozen jurisdictions with DROP programs around the country and found none that examined the frequency of long injury leaves.

San Francisco was the only jurisdiction The Times found that implemented a simple rule to prevent them: Any officers who received temporary disability payments would have their pension payments suspended until they became fit for duty again. When they returned to work, the payments would be reinstated.

Micki Callahan, director of San Francisco's Department of Human Resources, said the provision was introduced to prevent abuse. “Isn't it wasteful to spend this money for people who aren't even at work?"

Even with that provision, officials in San Francisco found the DROP program too expensive and discontinued it within three years.

One incentive for cops and firefighters to file a workers’ comp claim, rather than use their health insurance, is that their salaries are exempt from federal and state income tax while they’re out on disability leave for a job-related injury.

That means they take home substantially more of their salary while they’re home recovering than they would if they went to work. If they wait until they’re in DROP to take off a few months — or a year, or two — they receive pension checks on top of the tax-free salary.

The downside of the workers’ comp system, according to interviews with DROP participants, is the difficulty getting the city to approve ongoing medical treatment for cumulative injuries, especially if an employee claims several of them.

Claims adjusters working for the city are particularly slow to approve significant surgeries, such as knee replacements, employees said. They try to save money by encouraging employees to try weight loss, physical therapy and cortisone injections first, even if the employee’s personal doctor has recommended surgery.

The delays cost the city money, employees argue, because they end up on disability leave longer.

‘That last year was about me’

All that time away from the job has another negative impact, according to employees who have been through it: lower self-esteem.

“I hated it,” Renner said of the nearly three years he spent off duty waiting for, and recovering from, treatment for his bad back, sore knees and an injured thumb while he was in DROP. “You feel like a worthless piece of trash.”

Between salary and pension, the city paid Renner more than $650,000 for time off while he was in the DROP program, The Times analysis found.

Russell, the former police captain, said he would have loved to return for light duty during his nearly three years off, but his superiors never called to offer him that chance.

LAPD officials disputed that account, saying they have a policy of contacting employees who are out sick or injured every seven days, and that Russell was contacted at least 84 times.

Villegas said Russell should not have needed any special accommodation because “the captain’s job is a desk job. Certainly you can come back to answer phones and respond to emails if you want to.”

While it’s unlikely the department would bother pursuing charges years after the fact, Russell’s suggestion that he would’ve returned if contacted “may be evidence of criminal fraud,” Villegas said, because it implies Russell was actually able to work. “He’s suggesting that he’s healed if we would have called him,” Villegas said.

Russell’s time off began when he tore his right biceps reaching for a cooler in his garage before a Super Bowl party in 2012. That wasn’t a work-related injury, but while recovering from surgery the pain spread.

“I suddenly start having trouble with my wrists … just out of the blue,” Russell said. He was found to have carpal tunnel syndrome and had additional surgery.

After a long stretch recovering from that, he returned to the office only to have the chair collapse beneath him. He wound up on the floor with a reinjured wrist and a newly injured back, Russell said.

For each workplace injury, police and firefighters are allowed up to 364 days of injury leave.

As he recovered from his fall from the chair, Russell sought treatment for cumulative trauma to his knee. The city was slow to approve surgery to fix the problem, Russell said, so he never returned to work.

“That last year was about me,” Russell said. “It was about taking care of myself.”

The city paid him more than $830,000 for his time off during DROP, according to The Times’ analysis.

In her self-published autobiography, “Mama’s Curse,” former LAPD Capt. Tia Morris describes her 2006 diagnosis of breast cancer — the disease that killed her mother — and the months of successful treatment that followed. She also writes about her sense of betrayal five years later when she was passed over for promotion in the Van Nuys division — a little more than a year after she entered DROP.

“I felt defeated and irrelevant, so I was done for once and for all with the LAPD,” she wrote.

Instead of simply retiring with her pension and city-paid health insurance, however, Morris remained in DROP and started taking long disability leaves for injuries she said she had accumulated during decades on the force — collecting her salary and pension all the while.

She filed workers’ comp claims for carpal tunnel in both hands, pain in her neck, a sore elbow, a sore shoulder, a sore knee and a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection she claimed she’d contracted from filthy conditions at the department’s Southwest Division.

Of her carpal tunnel treatment in February 2012, she wrote, “I wasn’t happy about having surgery but I was happy to be away from work.”

With the exception of a few workdays in June 2012, she remained on injury leave until September 2013, when she retired, city records show. The city paid her nearly $470,000 for the time off in DROP, The Times’ analysis found.

Her husband, Percy Morris, filed claims for carpal tunnel, MRSA and a back injury while in DROP. He was paid about $476,000 for the more than two years he took off during the program, The Times found.

The injuries prevented the couple from doing their desk jobs at the LAPD — hers was administrative, he spent at least half his time typing reports — but they were far from idle.

Postcard from Cabo San Lucas

Photos posted to Tia Morris’ Facebook profile while they were both in DROP and Percy Morris was on injury leave show the couple embracing on the beach in Cabo San Lucas, where they bought a timeshare. In her autobiography, Tia writes about starting the theater production company shortly after entering DROP.

They staged plays and produced films written and directed by their daughter, pitching in with everything from renting theaters and furnishing sets to baking cookies to sell to audiences. It was all “perfect for our transition from law enforcement to a much happier place,” Tia wrote.

It was important, however, to make sure the hours she spent working for the family business did not overlap with hours she otherwise would have been scheduled to work at the LAPD.

“I did not want any work comp fraud issues,” she wrote, “so I was letter of the law.”

Since the program’s inception, not a single DROP participant has been charged with workers’ compensation fraud, court records show.

Twitter: @JackDolanLAT

Twitter: @GGarciaRoberts

Twitter: @ryanvmenezes

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.