California fire: What started as a tiny brush fire became the state’s deadliest wildfire. Here’s how

- Share via

Reporting from PULGA, Calif. — Before there was a spark, there was the wind.

On the morning of Nov. 8, as the sun rose over the isolated mountains in the Sierra Nevada, gale-force winds tore through the canyon. A fire outpost on the Feather River recorded blasts of 52 mph — a bad omen in a national forest that hadn’t had a satisfying rain since May.

From his station bunk at the head of Jarbo Gap, Capt. Matt McKenzie of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection woke to the sound of pine needles pelting the roof.

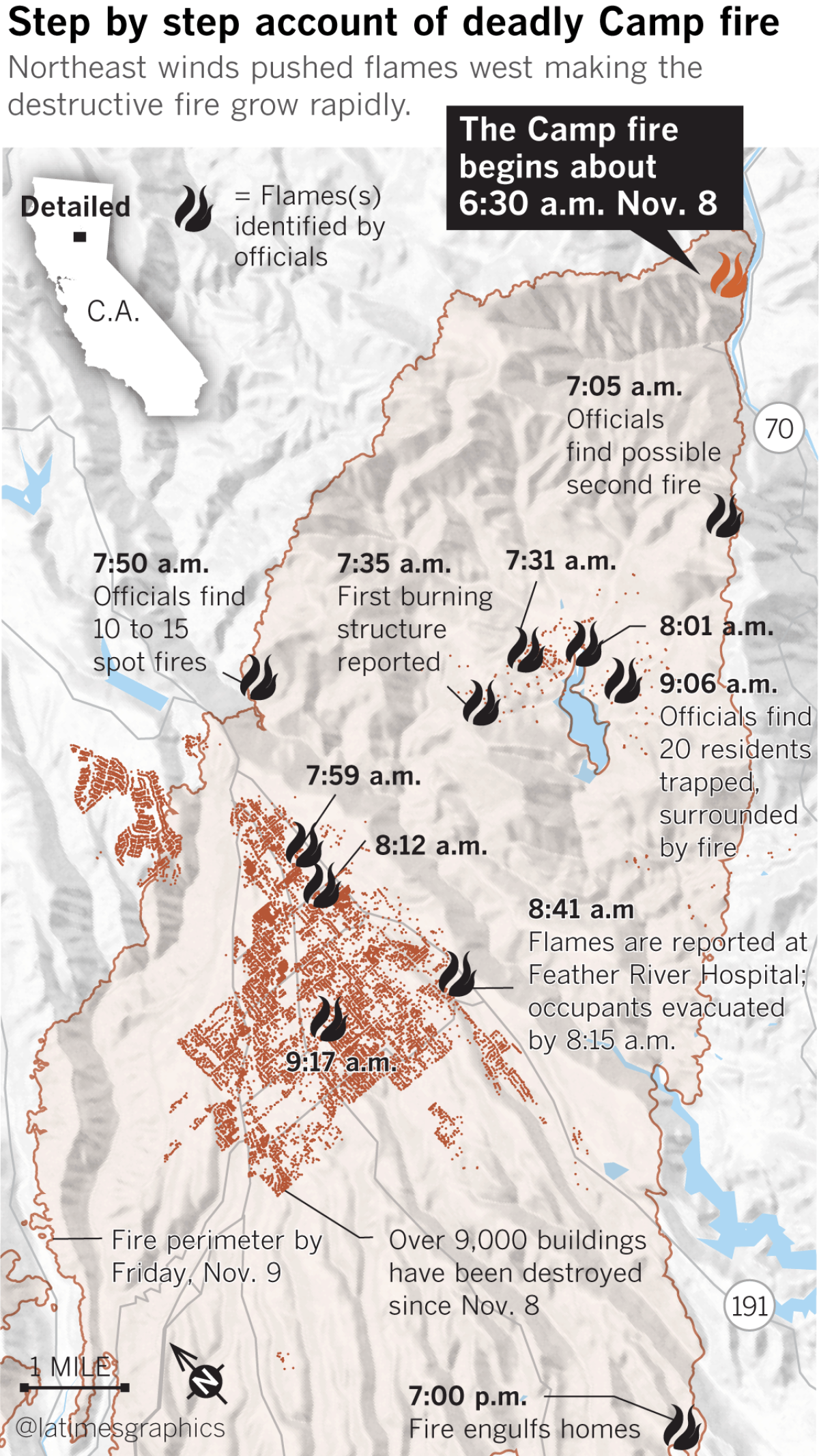

At 6:15 a.m., a Pacific Gas & Electric Co. high-voltage line near the Poe Dam generating station six miles away malfunctioned. A report of fire came at 6:29.

Fifteen minutes later, McKenzie stood at the dam looking helplessly across the river canyon at a 10-acre fire on the rock slope above. He had no way to reach it. Its unpaved access route, Camp Creek Road, clung to the mountain so precariously that rock slides threatened to erase it.

The last time he put a heavy wildland engine on the crumbling grade, it took an hour to creep a mile, mirrors folded in, a man walking beside each wheel to watch for collapse. It would be a death sentence to send a crew out there in a fire.

California’s professional wildfire strike forces make a regular practice of killing small grass fires — stomping thousands into anonymity each year. But this one was being lashed by a canyon vortex locals call the Jarbo wind.

McKenzie understood the immense capability of this little fire. It was the disaster he had trained for.

“This has got potential for a major incident,” he radioed. “Still working on access.”

He called for an evacuation of the nearby community of Pulga and ordered a slew of engines, water tankers, bulldozers and strike teams.

The wind was faster. Already, it lofted a blizzard of embers toward nearby towns. McKenzie appealed for “early up” of the helicopters and air tankers that could attack the fire from above. He was told he’d have to wait.

These are the victims of the California wildfires

Cal Fire planes don’t fly before light or if the wind is too fierce, and both the time and weather conspired with the growing fire on Camp Creek Road. People were trapped and dying in the mountain enclave of Concow and homes were burning at the top of the ridge in Paradise before a fleet of helicopters and tankers could lift off.

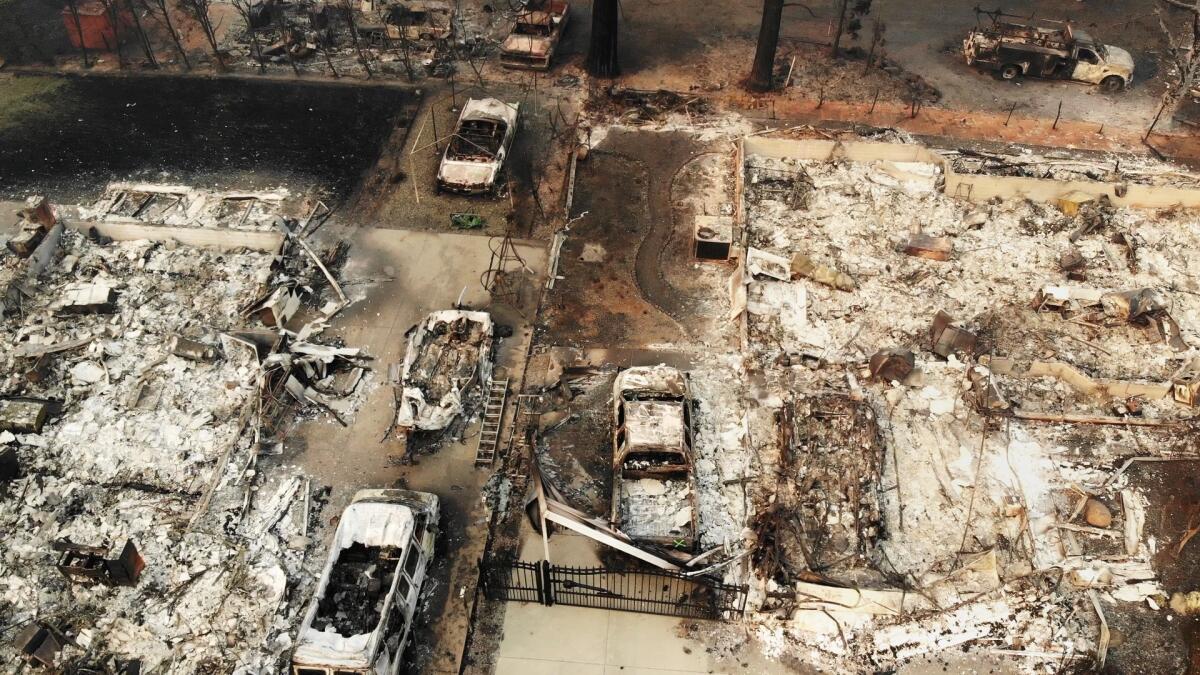

By sunset, the fire had swept 19 miles over an entire mountain, surprising, trapping, terrifying and killing — the most destructive and deadliest in California history. Concow and the city of Paradise are largely gone, adjoining mountain towns devastated.

Eight days into the search, the death toll is 76 and rising. Hundreds remain missing; some 50,000 residents are displaced, scattered to relatives’ spare rooms, motels and a Walmart parking lot turned refugee campground.

Survivors, emergency radio recordings and accounts by officials depict the chaos of that nightmare: a staggered evacuation plan that fell tragically short, residents with no warning to get out, and gridlocked evacuation routes that became fire traps, forcing hundreds to try to outrun the fire on foot.

The fire moved so fast — faster than emergency officials grasped, faster than evacuation orders could be acted on — consuming entire neighborhoods before people could flee.

7:40 a.m.: “We’ve got structures already burning down here.”

Susanne and Gilbert Orr were eating breakfast when they saw flames outside their kitchen window. Gilbert, 71, ran out with a rake and a hose, “but there were little fires everywhere,” said Susanne, 68. “Everywhere.”

The couple lived in Concow, a small mountain community of homesteaders, retirees and marijuana growers a little more than five miles upslope from where the fire began. Within an hour of McKenzie’s initial assessment, embers were battering the town. Four minutes after that, a home was ablaze. A minute later came orders to evacuate. More homes caught fire.

The Orrs piled into their old Trans Am with their dog Duke. As they made their escape, they fended off sparks that blew in through the car’s broken window.

8:07 a.m.: “They’re trapped.”

A fallen tree blocked Hoffman Road, Concow’s main escape route. It trapped a state fire crew and 20 residents.

McKenzie radioed instructions for the fleeing villagers to seek the relative safety of a park. Out of desperation, some plunged into a creek feeding the Concow Reservoir. A fire captain and his crew deployed their emergency shelters to shield civilians as the heat blast rolled in. “We might have injuries,” a firefighter radioed, and an advance call went out for medics.

When it passed, firefighters radioed they were coming out with three people who had burns over half their bodies. A 90-year-old man was pulled from the water with hypothermia. At least eight people were killed.

8:12 a.m.: “Spot fires in backyards ...”

Even as Concow burned, state fire crews saw Paradise was in peril. A fire chief calling to evacuate the entire eastern flank of the town came across the radio at 7:46 a.m.

Paradise had been spared from the frequent wildfires of Butte County, though one 10 years ago stopped at the edge of the old mining town. The evacuation had been a disaster. Three of the four major roads out had caught fire. Evacuees were trapped for three hours in gridlock, leaving them defenseless if the fire had come.

A grand jury report and county fire plans said Paradise needed a way to get everyone out quickly at once. Instead, Paradise leaders divided the town into evacuation zones that could be emptied a few at a time.

Following the lead of other fire-prone counties, Butte County contracted for a private warning system to alert residents in danger — if they had the foresight to sign up. The Paradise emergency operations director estimated no more than 30% of citizens were on the list.

The result was that as the Camp fire entered Paradise, the evacuation order issued at 7:46 a.m. covered only the eastern quarter of town. Evacuation orders weren’t given to the rest of the city for nearly an hour.

Within two minutes of the broader warning, the first major traffic jam was reported. Then the evacuation corridors caught fire, as they had a decade before.

9:43 a.m.: “It’s not looking good to get people out.”

Nichole Jolly knew it was coming. The 34-year-old Paradise native, a surgical nurse at Adventist Health Feather River hospital, had received a one-word text from her husband earlier that morning: “Fire.” He texted again a minute later, “Huge.”

Staff at the hospital had begun moving out its 67 patients before the official evacuation warnings. Now Jolly searched the halls and bathrooms to be sure no one was left. As she pulled out of the parking lot, the human resources building was on fire.

Pentz Road, one of the town’s four evacuation routes, was jammed. So was the crossroad to the other nearest exit route. Cars inched forward as brush burned on both sides of them and embers rained. People yelled to be heard over the sound of exploding car tires.

The fire caught up to Jolly on Pearson Road, blasting her car with heat. She reached for the stethoscope slung around her neck and flinched as the metal burned. Her steering wheel was melting — the plastic stuck to her hands.

As her car caught fire and began to fill with black smoke, she called her husband. “Run,” he told her.

Jolly fled for safety to the car ahead of hers, but it too was abandoned. She ran on.

The rubber on her shoes melted into the asphalt. The back of her scrubs caught fire, blistering her legs. She tried another car, but it wasn’t moving.

“I can’t die like this,” she told herself. “There’s no way I’m going to die sitting in a car. I have to run.”

LIVE UPDATES: The latest on the California wildfires

Jolly plunged into the smoke, now blinding, and ran with her hands stretched out in front of her. She hit firm, hot metal. A firetruck.

Two firefighters lifted her in and radioed for help, pleading for a water drop. The crackled response came back: “Impossible.”

“Start turning people around,” a dispatcher said. “Get them going toward the hospital.”

They went back through the fire, back past the burning carcasses of a California Highway Patrol car and a state fire vehicle, also abandoned, their occupants fleeing on foot.

The hospital was still standing.

9:58 a.m.: “People are abandoning vehicles on Skyway. We’re going to try to push them out of the way.”

The gridlock was happening all over Paradise. On a typical day, the town’s only four-lane road, Skyway, ferried 1,200 cars an hour — and that was at rush hour. Now it was being asked to empty a city of nearly 27,000.

The cars backed up into the feeder streets, and into the secondary roads that fed those.

On Edgewood Lane, a long residential drive with only one way out, evacuees inched forward through smoke, then flames. Motorists scrambled from their cars.

William Hart, 44, a professional umpire accustomed to the split decisions of baseball, scooped up passengers. A panicked woman by the side of the road. Two dogs. One of them hesitated. “Get in, dude!”

The fire surrounding them was hot and white. It roared like the engines in a drag race. He saw a human form on fire in a car. Behind him, “a tsunami of liquid fire” as high as the trees barreled toward him. Somehow his car kept going.

On the road, at least five people were killed.

In the thick of the evacuation chaos was Butte County Sheriff Kory Honea, enveloped in what he called the “fog of war.”

The county’s dispatch center was flooded with 911 calls. There was a backlog of 40 people trapped and needing evacuation assistance. Honea paused at Skyway and Elliott Road to direct traffic, as if he could will it to move. The Paradise city police officer he assisted was his daughter. It was hard to leave.

Honea feared he might not see her again.

10:02 a.m.: “Woman in active labor ... she will be honking her horn.”

Jolly was back at the hospital when she heard an alert that a woman trapped on Skyway was in labor.

Though parts of it were burning, a makeshift clinic sprang up in the ER parking lot. Fire refugees stumbled in, including elderly women carrying Chihuahuas and Pomeranians.

The prospect of a woman in labor was more problematic. Fire officials radioed that she had complications requiring a caesarean section. With a flashlight, Jolly crept back into the hospital for surgical supplies — sutures, sterile dressings, a bassinet.

The patient never arrived. Jolly could find no one who knew her fate.

10:16 a.m.: “Fire is too intense.”

As bad as it was in the evacuation madness, Alexandria Wilson, 21, was still at home in her terry slippers, watching the stream of cars on Skyway. Her boyfriend was convinced he could put out the spot fires.

Wind gusting at 72 mph blew the flames sideways, propelling them house to house so quickly that heat did not have time to bake the leaf canopy of the trees above. Houses incinerated while the trees around them remained unscorched.

Wilson saw drivers give up on Skyway and jump the curb to try their luck on the new Paradise bike path. The rest of her family had already left. “Babe,” she pleaded with her boyfriend. “Babe ...”

After he promised to follow her, Wilson started off alone and took the car and the two dogs. Within blocks, she was trapped in the gridlock. An officer ran by telling drivers to pull over and run.

In slippers, towing two dogs, Wilson did just that. Down the road, she joined a group of elderly women and their pets in the back of a pickup. But amid the explosions, one of the dogs bolted. She cried as she watched the German shepherd mix crawl into a drain pipe. Harley!

“Your dog is going to be fine. Your dog is going to be fine,” the women said, some of them crying too.

Then the truck stopped, blocked by traffic.

For a second time, Wilson ran, but now officers steered her back the way she had come. She found refuge in a school bus, where passengers cried and wailed as the driver rammed abandoned cars blocking the road. In a desperate attempt to get around, he swung the bus toward a ditch, where it got stuck.

The buildings on both sides of the street were burning. Wilson climbed out the rear exit and resumed running. Take any car with keys in the ignition, officers shouted. “Just go.”

12:18 p.m.: “Don’t tell anyone to get out of their cars anymore. They are all on foot.”

Wilson’s feet burned through her slippers. There was no sight of her boyfriend. She was seven months pregnant and believed herself alone in the world. “Oh my God,” she thought, “What am I going to do with my son? What am I going to do at all?”

Emergency responders were trying to ram their way into Paradise. Blocking their way were more than 150 abandoned, burning cars and as many people on foot. Clusters of civilians massed at whatever safe spots they could find — in fields, at stores. Wilson joined those at an antiques shop.

Fire engine crews tried bumping the abandoned cars out of the way. They called in bulldozers. Behind them came buses to bring the refugees out, 40 to 50 people from one location, others left in a nursing home, and a preschool.

Wilson once again climbed into the bed of a pickup, still holding one dog. She joined a man with a cat carrier and a couple with two dogs. They rode on through the smoke and fire, never stopping.

Track key details of the California wildfires

At the end of the road was her boyfriend, who had arrived in the truck right before hers. And three days later, Harley resurfaced, burned but alive. The house they had abandoned still stood.

In Paradise, city fire hydrants eventually ran dry.

“We’re trying to save what we can, but it’s not looking good,” a fire engine chief said over the radio.

5:51 p.m. “Be careful. It’s coming out of the canyon hard.”

Anna Dise, 25, was at her father’s house in the foothills above Chico, keeping tabs by television on the nightmare four miles away in Paradise. Midday, their power went out.

With that went their awareness of the encroaching fire. Anna’s cellphone had no reception, and her father’s home had no landline.

Nobody drove by with evacuation orders or information. She didn’t know firefighters just up the ridge were alarmed. The fire was gathering for a new run.

The sky was black with smoke by 2 p.m., but it wasn’t until evening, after 7 p.m., that she saw the flames coming at them.

In the fires before, Gordon Dise, 66, had refused to leave his land, where he tinkered on motorcycles and was building a fountain. But this time, he helped Anna pack. They went to the car together.

Then without explanation, Dise’s father returned to the house. She yelled at him not to. She honked the horn. Still he didn’t come out. She tried to drive and realized the tires had melted.

By then the house was on fire and collapsing. Dise and her two dogs ran to a neighbor’s gravel drive, and she found enough water in a ditch to wet her jacket and hair.

Trapped in that spot, she watched her childhood home burn. She presumed her father was still inside. Flames came up beside and behind her, sometimes feet away.

Her fingertips burned. Her face was scorched. She tried dialing 911 and got through long enough to ask for a rescue, but none came. She could hear trees falling.

Eventually the sky lightened. Beyond the smoke was morning.

Dise could hear chain saws, firefighting crews at work on firebreaks.

She and her dogs walked toward them.

It will take ’10 to 20 years’ before Santa Monica Mountains look like they did before Woolsey fire »

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.