Cal State, faculty’s union reach accord over salary dispute

- Share via

For instructors such as Devon Hackelton, frustration over low pay and demanding working conditions has been mounting for years.

His anger is such that he was ready to walk out of his freshman English classes at Cal Poly Pomona, joining thousands of colleagues across California State University’s 23 campuses in an unprecedented strike that could have crippled the nation’s largest higher education system.

That action was put on hold Thursday after Cal State officials and the union representing faculty reached a tentative agreement over a long-running salary dispute. The five-day strike was scheduled to begin Wednesday. Members of the California Faculty Assn. must still approve any resolution.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

Even if the strike is averted, many of the issues that have plagued the “people’s university” for decades remain to be settled, faculty members and others said. They include a reliance on diminishing state funding, increasing enrollment demand, backlogs in maintenance and repair of campus facilities, and pressure to graduate staggering numbers of students from low-income households who would be the first in their family to attend college — as well as lagging faculty compensation, which has been at the heart of the current dispute.

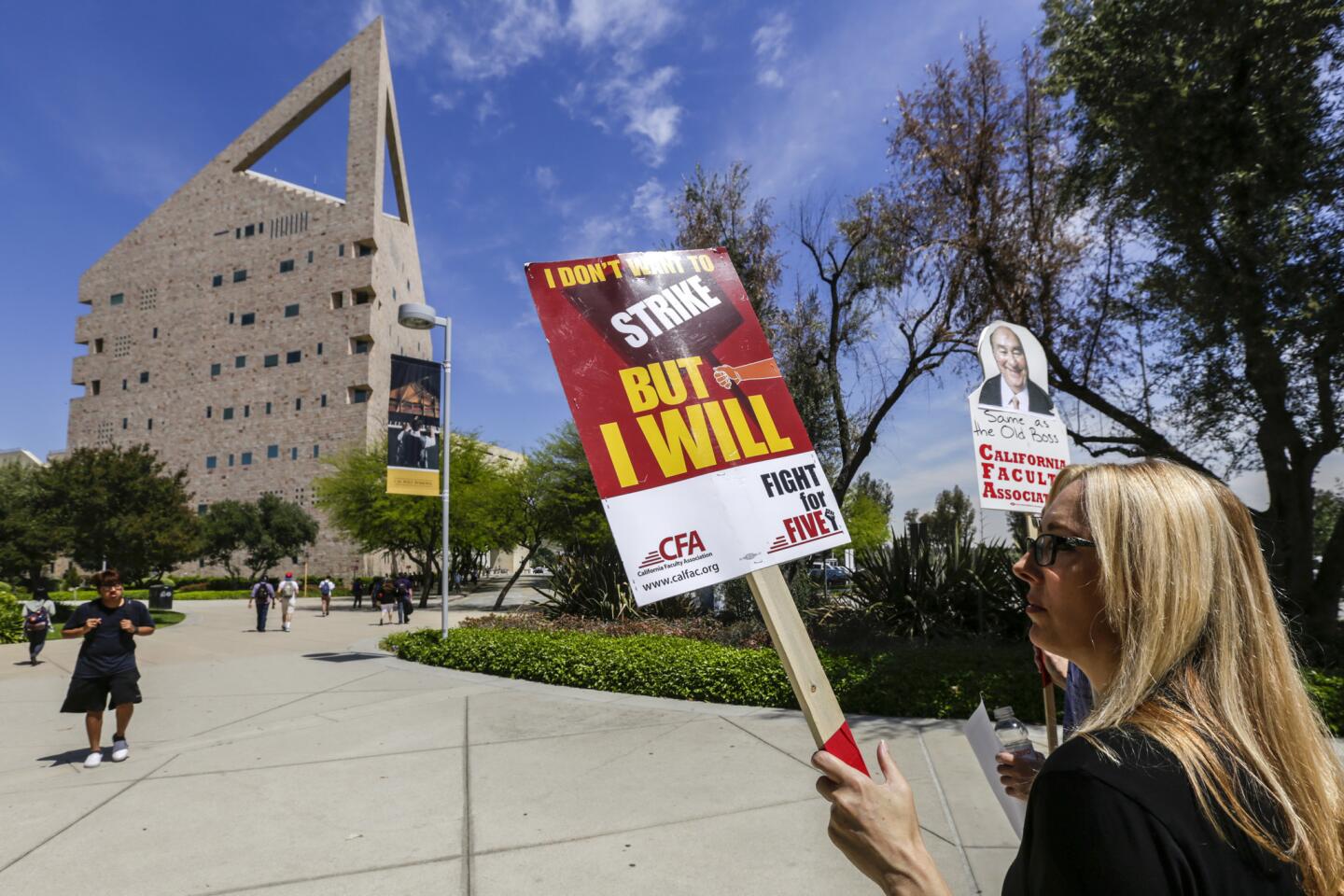

Tensions had been mounting. Earlier this week, Hackelton and dozens of his colleagues gathered in the back of the student center to strategize how to shut down the Pomona campus and made protest signs that said “I don’t want to strike but I will.”

His class sizes have grown in the last decade while his salary of about $53,700 has increased by less than $4,000. He works two jobs to make ends meet and traded his house for an apartment when the cost of living outpaced his salary. “The proverbial last straw has been hit,” said Hackelton, who has taught at the campus for 20 years.

The union, which represents about 26,000 professors, lecturers, counselors, librarians and coaches, has demanded a 5% pay raise, plus additional hikes for some faculty based on their length of service. Cal State Chancellor Timothy P. White countered with a 2% offer, arguing that any more would jeopardize other important priorities.

Details of the agreement were scheduled to be announced Friday morning by White and faculty union President Jennifer Eagan in a joint news conference.

Once ratified by the union, the tentative agreement will be voted on in May by the Cal State Board of Trustees.

University officials resumed talks with the union Wednesday in a final attempt to prevent what could have been the largest strike by higher education faculty in the nation, one that would have disrupted studies for more than 460,000 students.

But Cal State still faces a laundry list of problems:

The system lost more than $1 billion in funding during the recession. Even with gradual funding increases brokered under a budget deal with Gov. Jerry Brown, the system is still about $135 million below 2008 funding levels, White said.

Cal State is still dependent on state general funds to cover about half its operating costs, unlike the University of California, which relies more on tuition and other nonstate revenues.

State funding for the UC and CSU systems have declined dramatically since the 1980s, when Cal Sate received about $10,000 per student, according to data from the Public Policy Institute of California. In 2011, that figure had dropped to less than $6,000 per student, after adjusting for inflation.

Cal State has trimmed expenses in recent years by restricting the growth of enrollment, among other measures, but has relied primarily on tuition increases to help fill the funding gap, which is not politically popular or in line with the greater vision of public higher education in California, said Hans Johnson, senior research fellow at the institute.

“Our public higher education system has been critical to the state’s economic success,” Johnson said. “No one argues that.”

After doubling from pre-recession levels, annual undergraduate tuition of $5,472 has remained flat since 2011 and will remain that way next year as part of the agreement with Brown.

Enrollment throughout the system has increased about 20,000, but CSU has not been able to make room for everyone who wants to attend a Cal State school. Officials last fall had to turn away about 30,000 applicants who fulfilled all the admissions requirements.

Cal State leaders are now seriously considering a controversial plan to introduce small, yearly tuition hikes to contend with long-range funding needs.

The bigger picture issues driving the salary dispute have not gone away, said Steven Filling, chairman of the Cal State Academic Senate. Lower salaries at Cal State have made it difficult to hire new instructors, especially those considering posts in high-cost areas such as Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Jose, he said.

“Who wants to be — ‘Great, I spent 12 years in college, I’ve got this job that I care about but I can’t afford to buy a house, I can’t afford to send my kids to college’ — those are not things that tend to attract really good people, and to me, that speaks to the sustainability of CSU,” said Filling, an accounting professor at the Stanislaus campus.

Students also are straining under the pressures. At Cal Poly Pomona, many awaited updates on whether to go to class, worried about missing even two days of face time with their professors.

“I want to graduate on time,” said Royal Chen, a fifth-year psychology major who commutes every day from Altadena and works three jobs to help pay for books, student loans, gas, food and rent. Cal State’s budget woes are affecting her studies: “This year, there were only like 15 offered courses in the psych department, and I’ve taken 13 out of the 15 courses,” she said.

In her five years on campus, parking costs have jumped 50%, and she has noticed more students in her classes but “no new faces” among her professors.

Pomona student Laura Hasbun said many of her professors work part-time jobs at more than one campus, and she recently had to drive to Fullerton to find her professor and get help on a paper. “That was my gas money, my parking money, my time,” she said.

More than half of Cal State faculty members earn less than $38,000 in annual gross income, according to the faculty union. That figure includes part-time instructors. Annual salary for a tenured full-time professor averages $96,660 for a nine-month school year, according to CSU.

An analysis of the system’s budget, conducted on behalf of the union by an accounting professor from Eastern Michigan University, found that Cal State had about $500 million in excess cash flow in 2015 and more than $2 billion in reserves.

Cal State officials have disputed the union’s income figures but said they were sympathetic to its position.

“We don’t disagree that our faculty [pay is] below-market,” White said last week in a meeting with The Times editorial board.

The challenge, he said, is balancing faculty compensation against the costs of higher enrollment, academic support programs and maintenance and upgrades to buildings and outdated technology.

The salary demands all told would cost the Cal State system about $102 million a year, he said.

Ultimately, every one of Cal State’s top priorities is underfunded, White said. “The only way to achieve our shared goals for students, faculty and staff is greater financial investment by the state.”

Twitter: @RosannaXia

ALSO

Cross has no place on L.A. County seal, judge rules

Rain moves into Southern California and will linger through Sunday

Social workers charged with child abuse in case involving torture killing of Gabriel Fernandez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.