Longtime L.A. civil rights leaders dismayed by in-your-face tactics of new crop of activists

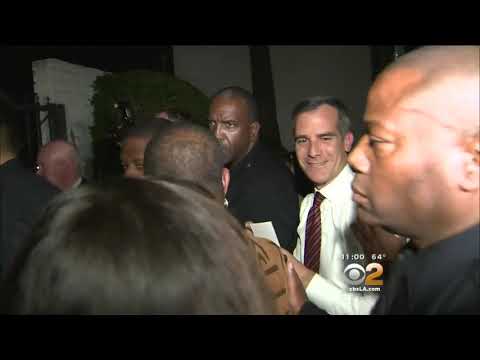

Pastor Kelvin Sauls, far left, from Holman United Methodist Church, listens as community activist Najee Ali denounces recent behavior by Black Lives Matters members against L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti.

- Share via

Long before Black Lives Matter made a mark in Los Angeles, there were the Rev. Cecil “Chip” Murray, Najee Ali, Earl Ofari Hutchinson. They and a handful of other black civil rights and religious leaders led the charge whenever issues of race and police brutality arose in South L.A.

They organized marches and held news conferences. But they also broke bread with L.A.’s political establishment, seeing it as an effective way to bring reforms.

Now there are new kids on the block, and they are shutting down freeways, disrupting community meetings, and camping outside LAPD headquarters and Mayor Eric Garcetti’s Windsor Square home.

Earlier this month, they confronted Garcetti at a forum in a church, eventually following the mayor—chanting along the way—to his car.

Rowdy crowd confronts Mayor Garcetti in town hall meeting

Inside and outside Holman United Methodist Church, longtime L.A. activists witnessed the scene, aghast. Embarrassed. Angry.

The hundreds of members of the fresh crop of community activists—many of whom came of age during the 1992 Los Angeles riots—reject the traditional tactics of the “old guard.” Despite their relative youth, they have adopted acts of civil disobedience used during the 1960s civil rights era and are more interested in pushing city officials and politicians to make change than in sitting on their commissions and boards—and waiting.

United under the banner of the national group Black Lives Matter, they are actually a loose coalition of organizations that believe that a more in-your-face approach to issues like excessive use of police force is not only more effective, but justified.

“You can’t attempt to employ 1980s and 1990s strategies in a 2015 moment,” said Pete White, founder of Los Angeles Community Action Network and a member of Black Lives Matter. “There’s a push back against methods and individuals whose message did not work.”

For the veteran activists—many of whom grew up in the era when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. preached nonviolence—the actions of some of the protesters distract from their message.

“With Black Lives Matter being a new organization with young activists, they don’t have the experience or discipline to be more effective advocates,” said Ali, the director of the advocacy group Project Islamic Hope. “They seem like a one-trick pony and all they can do is disrupt and make noise.”

The distinct approaches have caused a rift between activists like Ali and the young bloods—an echo of the kind of ideological disagreements that have surfaced within the world of black activism over many generations.

The protest over Garcetti at the West Adams forum last week laid L.A.’s latest version of it bare.

The Rev. Kelvin Sauls, a part of the established group of black reformers, invited Garcetti to host his first town hall meeting with area residents at his church. Eventually the hourlong discussion was interrupted by protesters affiliated with Black Lives Matter.

About 50 demonstrators turned their backs on the mayor as he spoke to a crowd of several hundred. When Garcetti attempted to leave, the demonstrators surrounded him and chanted as he walked to his car. One activist jumped on the trunk of the car as the mayor stepped inside.

In the following days, each side held dueling news conferences.

Patrisse Cullors, co-founder of the national Black Lives Matter group, said Garcetti promised to work with the activists to hold a forum, but then went behind their backs and partnered with Sauls.

Later, a group of clergy and other leaders of well-known organizations demanded an apology from the protesters, accusing them of being disrespectful and using words that seemed akin to a public spanking.

“I was raised by strict Southern grandparents that told me that if I acted up in public then I would get my discipline in public,” said Xavier Thompson, president of the Southern Missionary Baptist Church. “We will not tolerate irreverent behavior.”

On Sunday, Garcetti had planned a return visit to Holman United Methodist Church. But Sauls said he decided to cancel the event after news of it was leaked online.

Jasmyne Cannick, a political consultant, said that the mayor appeared to be dividing the black community into “good black people” and “bad black people,” essentially classifying Black Lives Matter among the latter by leaning on the generally older, seasoned activists and seeming to exclude the new voices.

With Black Lives Matter being a new organization with young activists, they don’t have the experience or discipline to be more effective advocates.

— Najee Ali, director of Project Islamic Hope

Last summer, in the hours before the Los Angeles Police Commission issued its ruling critical of two officers involved in the shooting death of Ezell Ford, Garcetti spoke with Hutchinson, Ali, and other traditional civil rights leaders to gauge the temperature among residents in South L.A.

Later, he invited the same group of black leaders to a meeting at City Hall to talk with Matt Johnson, an entertainment lawyer he appointed as the president of the police commission.

Members of Black Lives Matters said they did not receive a call or an invitation to the Johnson meeting. The group had been lobbying the police commission to hold the officers responsible in Ford’s death and were vocally opposed to Garcetti’s selection for the commission.

The mayor’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

“What those who are being targeted often do is use a divide-and-conquer strategy,” said Fredrick Harris, a political science professor at Columbia University. “Perhaps this is a strategy to divert attention away from the demands of the more contentious activists.”

Robin D.G. Kelley, a history professor at UCLA, said that Black Lives Matter is reminiscent of the 1960s Student Non-Violence Coordinating Committee, which organized sit-ins to protest segregation.

These groups “are called outsiders, troublemakers, disruptive and never had the kind of political legitimacy that people expected them to have,” he said. “But they were able to win concessions.”

Cullors held the first Black Lives Matter meeting in 2013 after demonstrators took to the streets to protest a jury’s acquittal of George Zimmerman, a Florida man who shot and killed black teenager Trayvon Martin, who was not carrying a weapon. About 30 people, mostly college students, showed up, said group organizer Melina Abdullah.

“Black Lives Matter” became a rallying cry during protests after the shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., in August 2014 by a white police officer—and again in L.A. during protests over police killings of black men around the country.

Abdullah said that Garcetti has forced the group members to take a “hard-line agitation approach to him when we could be working …with him.”

Despite the tension, both groups of activists said they are willing to work together toward a common goal.

“This is not about the black community airing out its dirty laundry,” Thompson of Southern Baptist Missionary Church said. “We will come together behind closed doors.”

Twitter: @AngelJennings

Emily Alpert Reyes contributed to this report.

ALSO

Victim lands on 5 Freeway sign after Glendale crash

Beverly Hills water wasters ‘should be ashamed,’ state regulator says

USC’s Pat Haden steps down from College Football Playoff committee

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.