‘How do you explain love?’ Finding community, friends and more at L.A.’s Braille Institute

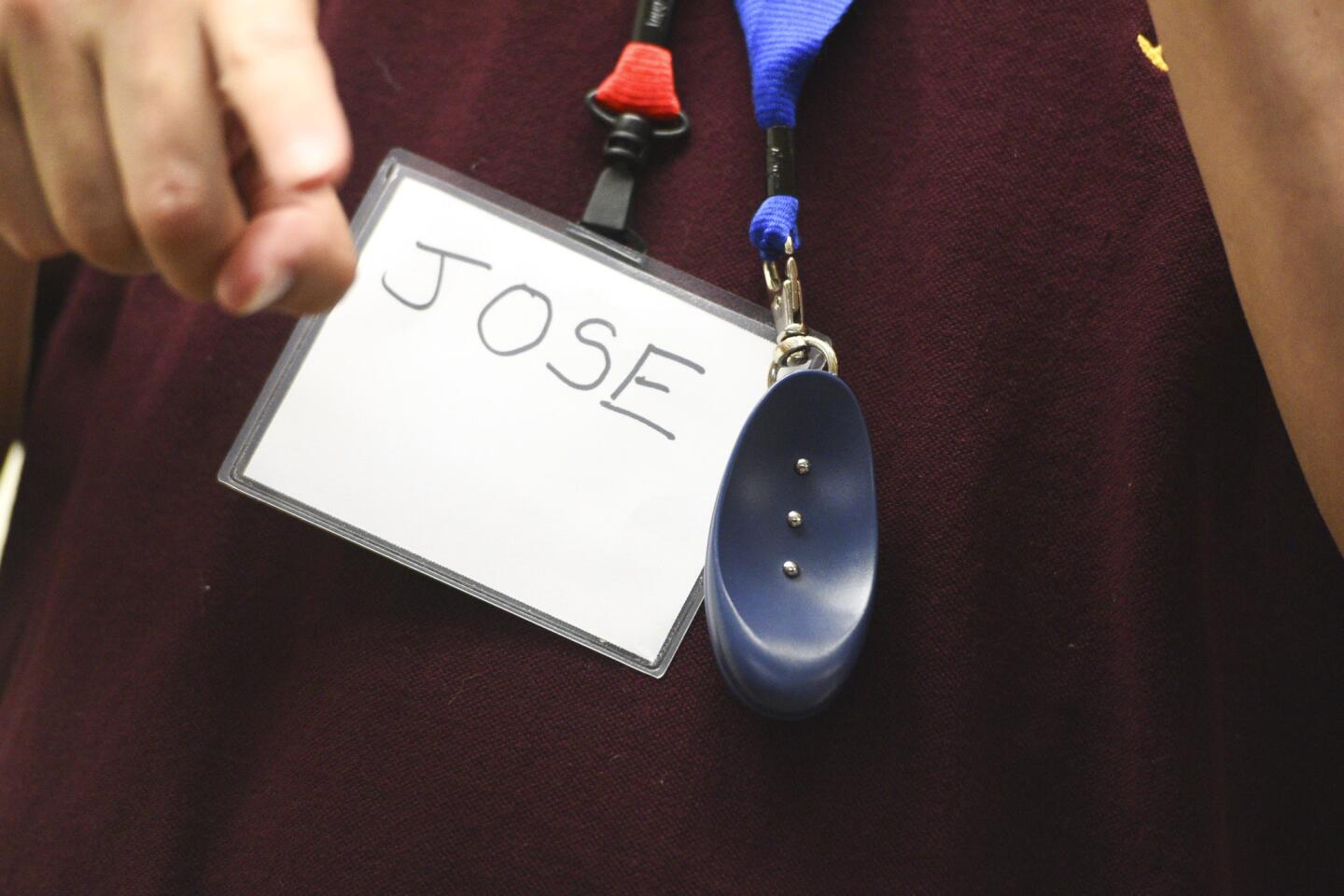

Tania Amaya uses sign language to speak to her husband, Jose.

- Share via

Tania and Jose Amaya are both a little shy, but ask them how they met and they’ll light up. She’ll blush. He’ll grin.

She was a computer teacher at the Braille Institute in East Hollywood, soft-spoken and sweet. He was a volunteer, deaf and legally blind, unable to speak. She was enrolled in deaf studies at Cal State Northridge. He’d help with her sign language homework.

They’d speak in a language for the deaf-blind, called tactile sign language. She’d sign, and he’d hold his hands over hers, reading the movements of her fingers. They’d make each other smile.

By the time they learned to communicate, something else happened: They fell in love. Next month, they’ll celebrate five years of marriage.

Asked recently what attracted them to each other, Tania signed the question to Jose, and they chuckled.

“How do you explain love?” she asked.

It’s the kind of thing that happens often at the Braille Institute. People — many of them sad and scared after starting to lose their vision — find community. They find friends. They find mentors. And, sometimes, they find love.

The institute recently lauded those relationships in a social media campaign called #loveatbraille, with couples and friends cheesing for the camera beside cutout hearts to “celebrate finding hope and love in our community.”

“It’s about redefining hope. People come here thinking they’re useless to other people and that they’ve lost their independence,” said Anita Wright, executive director of the institute’s Los Angeles center. “As students come here, they start to understand that there’s more to life than just the eyes, and that the eyes are to look through but the vision is through the heart.”

Jose Amaya, 36, was born deaf in El Salvador, with only the ability to hear extremely loud noises, such as emergency alarms.

His grandparents raised him but could communicate only with simple hand gestures. They didn’t know of any schools for deaf children, so while Jose’s brothers went to class, he stayed home, taking care of the farm animals and planting fruits and vegetables.

At 10, he moved to California to live with his parents, who had come to the U.S. years earlier. He finally started learning American Sign Language in school. But when he was about 12, his peripheral vision started getting fuzzy. He was slowly going blind.

Earth Kidkul from Braille Institute Los Angeles shows how people who are blind can use an iPad to send email.

Jose has Usher syndrome, a condition that affects both hearing and vision. Retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative eye disease, has deteriorated his sight so much that he now can make out only blurry shapes. He prays it won’t get worse.

When Jose started coming to classes at the Braille Institute in 1999, there was a petite young receptionist with big brown eyes and a kind smile. He wanted to talk to her but didn’t know how. She didn’t know sign language.

“I could see better then,” Jose signed, with Tania translating. “We didn’t know each other. It felt kind of awkward, how to communicate.”

Growing up nearby, Tania Amaya, 40, often walked by the Braille Institute but never really knew what went on inside the austere concrete building on Vermont Avenue.

She started volunteering there while taking classes at Los Angeles City College next door and quickly fell for the place. In 1999, she took a job as a receptionist. She watched the deaf-blind students talking with each other, signing into each others’ hands, feeling the words.

“What a beautiful language,” she thought.

Jose wanted to take care of himself. So, in 2001, he moved to Sands Point, N.Y., about an hour’s drive northeast of Manhattan, to attend vocational and independent living classes at the Helen Keller National Center for Deaf-Blind Youths and Adults.

“I had never before seen so many deaf and blind people,” Jose said. “We socialized and communicated. We just enjoyed chatting.”

On Sept. 11, 2001, he took a cab to work for a morning shift at his new job at a clothing store in another nearby suburb. Then the planes flew into the World Trade Center.

“They called an emergency alert,” Jose said, signing rapidly. “I could hear that loud alarm. We had to stop what we were doing. They told me we had to leave now. I didn’t know what to do. How can I leave?”

Jose walked with a cane at the time, his vision better than it is today, but still not good. Co-workers told him cabs weren’t running, nor were buses. His boss helped him get to the Helen Keller center, where everyone had worried about him, alone in the chaos.

Jose graduated from Helen Keller in 2002 and moved into his own apartment. But the economy took a hit. He lost his job.

He moved back to California and started volunteering at the Braille Institute. Tania was by then teaching computer classes and studying sign language. She introduced herself and told him she was still learning — could he help her?

They had study dates at Starbucks, having signed conversations, getting to know each other. He encouraged her to become an interpreter. They dated for two years before, one night at dinner, Jose asked: “Would you like to marry me?”

Jose now works at a clothing store in Northridge, and Tania teaches in the same Braille Institute classroom where she’s worked for 15 years. She helps the visually impaired learn how to type — the kind of patient works that on a recent day involved explaining keyboard shortcuts to a man trying to cut and paste words without being able to use a mouse.

The Amayas’ marriage is like any other: There’s constant learning. Like all couples, they fight sometimes. But they can’t yell at each other from across the room — they have to touch each other’s hands to talk, even if they’re mad.

“Many people think the same thing, ‘Oh, he’s deaf, that means you guys never argue,’” Tania said, laughing, her cheeks pink. “Well, of course, we do.”

Jose, a big grin on his face, showed what he does when they fight: He yanks his hand away from hers so they can’t talk.

Every Friday, the Amayas hold an open lab for blind-deaf people at the Braille Institute, where all classes and services are free. Jose and his guide dog, a golden retriever, commute by bus from the couple’s Van Nuys home.

On a recent morning, a deaf-blind man, Paul Hoffard, came in with his iPhone. He uses a Braille device to type on it, and the Bluetooth connection didn’t work. The device was still synced with his wife’s phone — she’s blind and deaf too.

Jose sat with him, and they held hands, signing, fingers flying. Jose donned a thick pair of specialized glasses and inverted the colors on the iPhone screen, trying to make out the magnified words.

For several minutes, he worked with the phone and Braille device, as Hoffard, an old friend, vented about the tech issues. Jose was having trouble with the needed fix — and it was a maddening mishap. He was trying to enter a serial number but couldn’t see that he was typing too many zeroes. Tania helped figure it out, and Jose signed the good news to Hoffard.

“It worked!” Hoffard signed. “Thank God! Thank you!”

The Amayas both smiled.

[email protected] | Twitter: @haileybranson

ALSO

Victim of plane crash on San Diego County freeway was a Roller Derby skater

Homophobia, drugs and mental illness may have led to gay man’s killing and father’s arrest

This year’s election could usher in a liberal ‘supermajority’ on L.A. County supervisors board

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.