- Share via

Alex Bogancha lay in bed, restless as he and a friend talked on the phone about whether Russia would invade Ukraine. It was before dawn on Feb. 24, 2022. He hadn’t slept. War was all he could think about.

A few hours later, a thunderous explosion answered his question. A Russian missile struck near his home in Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine.

“It felt like it was right outside my window,” the 18-year-old said.

Bogancha, his parents and his 14-year-old sister quickly loaded their dog, Lorik, and a few days’ worth of clothes into their car. They joined a sea of traffic heading west.

Los Angeles Times photographers document the battle in Ukraine after Russian forces invaded nearly a year ago.

“Everybody was scared,” Bogancha said. “Nowhere seemed to be safe. We didn’t know what to do.”

For nearly a week, the family kept driving, sleeping in their car. Eventually they reached Austria, where another refugee helped them get an apartment. “We were lucky to find a place to live,” Bogancha said.

They were grateful to have made it out, but Bogancha’s father, Andrii, worried about the future for his son, who had been in the middle of his freshman year at Kharkiv National University. The father had hoped a quick end to the war would allow the young man to continue his studies, but the fighting kept going.

Then came an unexpected offer of help in a WhatsApp message from a woman 6,000 miles away in Tarzana. She knew something special about the family’s history that would alter the course of his son’s life.

“I never believed in destiny,” Bogancha said. “But after this situation, I’ve changed my mind.”

An 80-year-old debt

The day was bitterly cold as Zhanna Arshanskaya Dawson desperately knocked on the door of the Bogancha home.

It was winter 1941. Dawson, 14, had trudged for miles in the snow, holding fast to five sheets of music, Frédéric Chopin’s “Fantaisie-Impromptu,” tucked under her clothing and her father’s final words in her ears: “I don’t care what you do, just stay alive.”

That day, Nazi troops had rounded up Dawson and her family and sent them, along with other Jews, on a 12-mile march toward a ravine at the southern edge of Kharkov, as the city was then known. Just a mile from the destination, Dawson’s father bribed a guard with a gold pocket watch to let his daughter escape.

She fled, hiding in a crowd of onlookers, never to see her parents or grandparents again. They, along with about 16,000 others, were executed on the edge of the ravine, known as Drobitsky Yar.

Dawson sought refuge at the home of a non-Jewish classmate, Nicolai Bogancha. She hoped his family — whom she knew as “good-hearted people” — would let her in.

Just before Nazi Germany invaded Hungary in March 1944, Jewish youth leaders in the Eastern European country jumped into action.

When his mother answered the door, she pulled Dawson inside to safety.

Two days later, the Bogancha family heard that Dawson’s 12-year-old sister, Frina, was nearby, hiding with another family. They took her in too. Frina, who died in 2019, never revealed how she escaped.

For two weeks, the girls hid in an underground fruit cellar whenever they were spooked by an unexpected noise or visit.

But the sisters were precocious piano players and local celebrities. Everyone knew they were Jewish. What if a neighbor spotted them? They needed a new plan.

They adopted new birthdays and names. Zhanna became Anna and Frina became Marina. The Boganchas helped them devise a story to explain why they were suddenly orphans — their imaginary father was a Russian army officer killed in action, and their mother had died in a bombing.

The Boganchas arranged for a horse cart to take the girls to the city outskirts. From there, the girls made their way to an orphanage, where a piano tuner eventually heard Dawson play. He introduced the two girls to a theater director who was in charge of entertaining German soldiers. The sisters performed for them throughout the rest of the war, securing their survival.

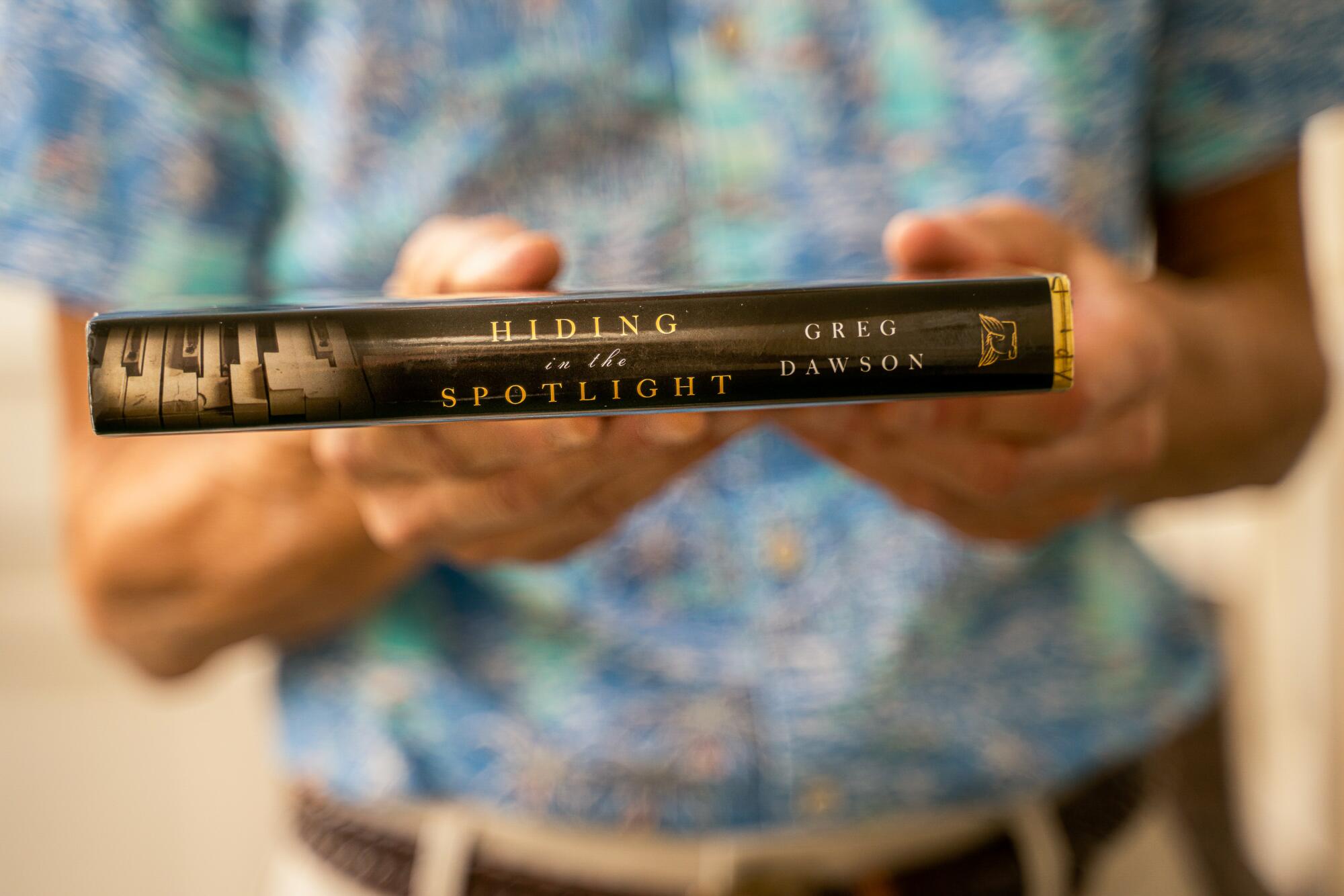

Years later, after the sisters immigrated to the U.S., after they attended the Juilliard School of Music in New York, and after Dawson married and began to teach music at Indiana University, she told the story to her son, Greg Dawson, who wrote a book about her experience, “Hiding in the Spotlight: A Musical Prodigy’s Story of Survival.”

“I was not playing for them,” Dawson told her son. “I was playing for my mother and my father and for the music. For Beethoven, for Mozart, that’s who I was playing for.”

The book becomes key

In 2013, Marina Orlovetsky of Tarzana was given a copy of the book. She read it in a single sitting.

“I just couldn’t stop reading it,” she said.

Orlovetsky, 61, grew up in Kharkiv too, but didn’t know the Drobitsky Yar tragedy happened in her hometown. Her Soviet-era school books never mentioned the word “Holocaust.”

For her, Dawson’s story was key to unlocking the true history of her birthplace. She set out to find her and discovered Dawson was living in Atlanta. After spotting her phone number online, Orlovetsky called, and the two spoke in Russian for nearly three hours.

“She told me everything,” Orlovetsky recalled. “That was how our friendship began. I was fascinated by her story. It was like part of my life.”

A couple of months later, she met Dawson and her son at a Holocaust Remembrance Day event at Chapman University in Orange County. At 86, Dawson had been invited to perform her signature piece — Chopin’s “Fantaisie-Impromptu.” She did so, effortlessly, from memory. The five pages of sheet music she had carried with her when she fled the Nazis were safe at her son’s home.

A few years later, Orlovetsky stumbled upon an article about the Holocaust that Andrii Bogancha had posted on Facebook. His last name caught her attention. His ancestors had saved her friend on that bleak day in 1941.

She sent him a message: “I just told him, please accept my biggest respect for you and your family,” Orlovetsky said.

She then followed up with a gift basket, which included a copy of “Hiding in the Spotlight” and a CD with recordings of Dawson’s piano performances.

A village of strangers band together

We asked Times readers who escaped Europe amid violent antisemitism and authoritarianism what they think about American democracy today.

Orlovetsky and Andrii Bogancha kept in touch over the years. As war once again approached Kharkiv, they exchanged messages. She stayed in touch throughout the Boganchas’ escape, then made her offer of help.

Once Andrii Bogancha accepted, Orlovetsky reached out to Greg Dawson and his wife, Candy, for assistance. They had been volunteering with Ukrainian Mothers and Children Transport (UMACTransport), which helps Ukrainian refugees come to the U.S.

“I’m a son of Holocaust survivors,” said one of the founders of the group, Michael Bazyler, a Chapman University law professor.

Bazyler’s mother would talk about growing up in a peaceful Ukraine — until “all of a sudden being bombed and running away with her family.” The Russian invasion has felt like “a repeat of the horror story,” he said. In another coincidence, he was the one who had invited Dawson to play Chopin at the Chapman concert where she and Orlovetsky had first met in person.

UMACTransport volunteers secured Alex Bogancha’s admission to Santa Monica College, and a local filmmaker, Andy Lauer, agreed to be his financial sponsor.

“I have an 18-year-old son. What if he was suddenly displaced?” said Lauer, who hosted a Ukrainian family of five last spring. “For me, it was personal.”

Michael Solomon, whose wife of 32 years died of cancer last year, offered to let Bogancha move into his poolside guesthouse in Santa Monica. “It just felt like the right thing to do,” said Solomon, 72.

Greg Dawson booked Bogancha’s flight. Orlovetsky shopped for necessities.

“All the pieces just came together,” she said.

Rebuilding with ‘such kind people around us’

On a wet January afternoon, nine months after she sent her WhatsApp message, Orlovetsky stood amid a group of well-wishers at LAX clutching a plate with a loaf of bread and salt — a welcoming gesture.

When they spotted Bogancha making his way through the terminal, the group cheered enthusiastically and waved American flags — then took turns embracing him. Orlovetsky FaceTimed Bogancha’s parents to let them know he’d arrived safely. His mother sobbed as he smiled and waved.

“He’s here!” Orlovetsky said in Russian. “He’s finally here!”

Bogancha was disappointed that he never got a chance to meet Zhanna Arshanskaya Dawson, who died at 95 just days before he arrived, but he’s quickly settled into his new life: He walks 15 minutes to school — his backpack slung on his shoulder, the school’s logo on his sweatshirt. The surf and sand are less than two miles away. The view is starkly different than in war-stricken Kharkiv.

Any day now, Bogancha’s parents and younger sister are expecting to receive approval to join him in L.A. He hopes to take them to Disneyland.

“I think we just need to be thankful for everything that we can, so that we can live,” he said. “We have such kind people around us.”

Since being in L.A., he’s eaten at In-N-Out Burger — a rite of passage — gone on hikes in Malibu, taken the bus on his own to explore Hollywood and walked along the Santa Monica Pier. He’s found comfort by practicing guitar and befriending other Ukrainian refugee teens through the messaging app Telegram.

The spike in antisemitism and other hate crimes in L.A. is grim, but a Jewish neighborhood in L.A. offers glimmers of hope.

Dawson had dementia for several years before her death, so her son wasn’t able to tell her about the Russian invasion or how the family had been able to reciprocate after the kindness the Boganchas had bestowed on her decades ago.

But the events have prompted Greg Dawson to reflect on his own legacy, including the birth of his granddaughter, who wouldn’t be alive if not for the risks that the earlier generation of the Bogancha family had taken.

Once all the Boganchas arrive in California, Greg Dawson, who lives in Florida, plans to host a memorial service in L.A. for his mother — and invite the village of strangers who helped the two families reconnect.

“What a shame it is that she is not able to see this part of the story. The way it comes full circle,” he said. “It’s further redemption of everything they went through and everything the Boganchas did for them.”

As for Orlovetsky, who served as the bridge between the two families, she says she “just did what every normal human being would do.”

“I just want to make them feel that every good deed will be [paid back] 1,000 times more when you do something good.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.