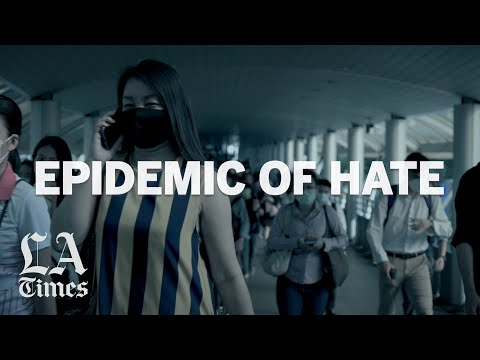

Asian designers and stylists speak out against COVID-19 racism

- Share via

Amid the surge of anti-Asian sentiment in America right now, a collective West Coast-East Coast voice stemming from the fashion community — including stylist Jeanne Yang and designers Prabal Gurung and Kimora Lee Simmons — has risen to speak out against the rhetoric and racism.

During the seven-week period from March 19 to April 30 there were 1,716 reported incidents of coronavirus-related attacks directed at Asian Americans, according to a recent study released by Stop AAPI Hate, a Los Angeles-based organization that was launched in March to record incidents of coronavirus-related discrimination against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

“Asian Enough” is a podcast about being Asian American — with guests like John Cho, Lulu Wang, Mina Kimes, Margaret Cho and Padma Lakshmi.

To put that number into perspective, just look at three years ago: The number of reports of discrimination against Asian Americans registered in 2017 at the website standagainsthatred.com, started by Washington, D.C.,-based Asian Americans Advancing Justice, came in at 200 for the entire year.

The rapid rise of racist incidents has driven several notable designers and stylists of Asian descent to use their large social-media platforms, appear on national news segments and forge relevant product collaborations to ease the already tense times and political division pulsing through the country and around the world.

Gurung is no stranger to speaking out on social and political issues ranging from immigration to LGBTQ rights. His spring 2020 runway collection examined what it means to be American, and the designer tapped journalist and immigration activist Jose Antonio Vargas to consult on the presentation. A diverse cast of models wore traditional symbols of Americana, including cowboy boots and boiler suits, and took the finale walk in pageant sashes posing the question, “Who gets to be American?”

“America is not a country. It’s an idea that different people can coexist and it ignites invention, innovation and growth,” said the New York-based designer. “In that, the Asian community has been a huge contributor. America doesn’t get to celebrate without our contribution.”

Gurung, who was born in Singapore and raised in Kathmandu, Nepal, has been speaking out consistently since February on his social platforms to combat rhetoric around Asian culture and specifically the reference to the coronavirus being called “the Chinese virus.”

Hoarding toilet paper, “forgetting” your mask, late-night hooking up? We want to hear your dirty little secret — anonymously.

“Our leaders should not be using terms like ‘Chinese virus,’” said Gurung of President Trump’s repeated reference to the coronavirus in late March. “I’m not calling the president racist. I’m calling him unaware of the fact that he shouldn’t be using it. There is no point vilifying someone and calling them racist. It is important to call them out and say, ‘Those words have a negative effect. Please consider rewording.’

“Our ancestors came here to make a living. They kept quiet, kept heads down and made a living,” Gurung said. “How I look at it is, our ancestors did that so we can speak up. I have to act for the future and next generations. Our forefathers fought for that quietly so now we have the responsibility to speak up.”

Gurung’s message during this pandemic aims to generate the same type of discussion as his collection as well as to press Asian communities to unify in support of one another, defying stereotypes of passiveness that have been long associated with Asian culture.

For designer Phillip Lim, getting the word out has meant turning to Instagram to post messages about the coronavirus being a human threat, not a foreign one. He has appeared on CNN and partnered with a pharmaceutical company to create packaging for hand sanitizers of which 100% of proceeds went to families suffering amid the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. His actions were sparked after seeing videos of racist attacks and hearing firsthand from colleagues about discrimination close to home.

“The march has gone virtual, basically,” said Lim of taking to social media and CNN as a megaphone against anti-Asian sentiment. “This is a new way of marching. We need to use our collective platforms to speak out against hate and have a collective united voice that is a show of solidarity and goodwill. With the rise of racism and a blame game, the only way to combat that is solidarity and to put back out love.”

Gurung and Lim were included in the 2020 A100 List, which was released in early May and put together by Gold House, an L.A. nonprofit organization formed to empower Asians. (May is Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month.) The annual list recognizes the 100 Asians, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders who have the most significance on American culture.

The global fashion industry includes a robust Asian and Asian American community with 48 of the 477 members of the Council of Fashion Designers of America identifying as Asian (with 31 identifying as Latinx and 19 as black). Well-known names include Rei Kawakubo, Anna Sui, Vera Wang, Lim, Jason Wu and Gurung, who have become pillars of the industry for establishing pioneer brands and aesthetics ranging from avant garde and eclectic bohemian to bridal.

Fashion designers of various ethnic backgrounds have been increasingly vocal about social issues they feel passionately about. Many are putting their views into their runway presentations and closing shows with provocative statements strewn across models’ finale looks or their own T-shirts.

Alarmed by the accounts of racism, other designers and stylists have been speaking out against anti-Asian sentiment and reported incidents of hate crimes. They’re also offering peaceful solutions forward to stand in solidarity as a community. The hashtag #notyourmodelminority has been spreading across social media and into conversations around Asian identity on a mission to defy the limiting connotations that Asian Americans are a monolithic group.

“I definitely do not fit into the model minority,” Lim said. “The model of America, what America is, is a belief system, not a physical appearance. We’re all an equal, collective conscience who have the will to fight for what’s right — to me, that’s the model minority — fighting for each other.”

The designer dissects the role that Asian stereotypes have in tempering and perpetuating racism. “It’s so systemic in Asian culture that our parents tell us to keep our head down, don’t make problems or ignore racism and it will just go away,” he said. “It’s so ingrained in our subconscious. That was a survival strategy. Now fast forward to today, and it actually does the opposite. It takes away your right for a voice and it takes away the opportunity to be seen. People are asking me, ‘What’s the right thing to do?’ You have to normalize your voice outwardly. Speak up. Combine the ideas of your parents of being mindful and respectful and amplify that with an outdoor voice.”

“I want to defy the very definition of what Asian is,” Gurung said. “I want to have a different representation of the narrative. We need a wide range of representation. It’s what is needed for people to understand.”

The designer also acknowledged the history Asian communities have had with other groups of color and the recent reports of racism against Africans in China during the coronavirus outbreak.

“It’s time for us to reflect and understand the racism in minority groups,” he said. “When minority groups fight, who benefits? Colonists, oppressors and the establishment benefit when we fight against each other. There is no need to be angry or vilify anyone, but it is important to ask what we’ve done and do to other communities and what we can do better. If you don’t speak up and don’t come in support of each other from within our community, how can we expect someone from another community to speak up?”

In the fight against the coronavirus, Gurung donated 2,000 N95 respirator masks to New York hospitals and frontline medical workers in partnership with the COVID Foundation. He, Lim and other brands launched T-shirts, hats and other goods with net proceeds going to the All Americans Movement, a campaign formed to support marginalized communities affected by COVID-19.

“We each have a role to play in combating the virus but also racism,” said Kimora Lee Simmons, the Los Angeles- and New York-based designer and founder of the iconic 1990s brand Baby Phat, which relaunched last year. “There are two sicknesses with a whole racially derogatory undertone that you have to fight at the same time. We have to combat it and treat each other with a little bit of respect because we’re all part of the bigger picture. We all have to do our part, call [racism] out when you see it, hear it or read about it.”

Jared Eng, fashion stylist and founder and editor in chief of the entertainment site justjared.com, recently had an Instagram account that posted racist remarks against Asians taken down.

“When I see it, I report it,” said the L.A.-based stylist. “It’s an uphill battle, but it’s not going to get anywhere by not doing anything. Especially in the fashion community, Asians have reached the forefront. There is a huge focus on them. Hollywood has not caught up as much, but it is important for Asian designers to support Asian talent. You want to support the community and push it forward.”

Celebrity stylist Jeanne Yang has been vocal on her Facebook page, including posting a recent opinion piece in The Times by actor John Cho and asking her followers to understand the negative ramifications that ranting about live animal markets in China has on Asians. Her role as an Asian American working in fashion has come full circle with her identity and the impetus to speak out.

“The reason that I went into fashion was that I did not see people that looked like myself on magazine covers,” said the L.A.-based stylist, who works with Jason Momoa, Keanu Reeves and others. “When you don’t belong, you do what you can to try and belong. You dress to be accepted. Once you get to a point where you do belong or have a say, I do feel as though, ‘Yes, I, as an Asian woman, should make it a point of being more outspoken.’ If we don’t all speak out, then should we wait until there’s nobody left to speak for us?”

She added that her anxiety lies in people focusing on blame rather than solutions or understanding. “Distraction is not going to get us back on the road to recovery,” said Yang, who will take part in Glamhive Live, a virtual fashion event of talks and panels featuring stylists and designers, on Saturday. “We need to figure this out, deal with the situation we’re in and get to solving it and helping people get back to work.”

It’s not too late. You can buy mom a houseplant for Mother’s Day and help a small business in the process.

It’s the kind of practical thinking Gurung can get behind: to work toward a collective understanding and path forward.

“You can decide to not go to Chinatown or not listen to K-pop, but when you go to an art gallery or hospital, you’re not going to escape us,” he said. “So it’s better if you understand our culture the way we’ve embraced yours. We continue to innovate and contribute to global creativity and the economy. We are here to stay and not going anywhere. It’s as simple as that.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.