- Share via

This story is part of Image issue 22, a meditation on the many definitions of the city’s favorite word: luxury. Read the whole issue here.

The camera running in my head is peering through the giant plate glass window of an art gallery, where two men inside gaze at Alexis Ralaivao’s “Sortir le grand jeu”: Sepia neck, in front of an eggshell background, poking out from a white blouse with a black pussy bow.

The guy on the left is wearing a blue button-down, oxford-cloth shirt (Brooks Brothers, J. Press, Rebuild by Needles, etc.) with a roomy cut, some tan chino shorts with big pleats, gray New Balance sneakers, and he is carrying a nice leather bag. The guy on the right is wearing something less fussy — a football jersey-esque Martine Rose polo shirt, some dark neutral shorts in a synthetic material, some contemporary runners in a different dark neutral, and he is carrying a Uniqlo crescent bag. Neither of them looks like he gets dressed in the dark.

Smart fashion is not about an aesthetic. The brand once called a cross between Comme des Garçons and Levi’s knows that it’s about putting something extra on it just for you.

“I like how delicate the light is,” Polo says. “But then you look at that little shadow on the collar, it makes her button-down pop.”

“Who says it’s a woman?” Oxford replies. “Also, that’s a button-up.”

Polo slumps his shoulders.

“Please f— off.”

“It’s an important distinction!”

“To you.”

“To people who care about getting things right. That’s a blouse, right? In a light fabric like that? Leisurely. If you put buttons on the collar, it’s a completely different garment.”

“Would it be?”

“I think so!”

“Pfft. Nobody cares about that stuff. To most people, a shirt with a collar is a nice shirt. If it has some buttons on it they’re still thinking fancy.”

“It doesn’t matter what most people think. For the kind of people this thing matters to, the little details matter. Their fancy is a fancier fancy. And if they’re expecting fancy and get met with a shirt collar with buttons on it, they’d be insulted.”

“I’m always expecting fancy when I see you, and yet here you are in a button-down collar. Should I be insulted?”

“Maybe,” Oxford smirks. “It’s the kind of thing I wear when I want to be reminded that I’m someone with a deeper capacity for fanciness than I let on.”

There’s so much importance woven into that little scrap of cloth perched on your clavicle. The fabric swings around the neck like a boomerang. The band lifts it up — the higher, the haughtier. It hugs the skin then flips out to the points in search of full expression. What that expression means depends on what you want the collar to do. It can be a frame, a stilt, a highlighter pen. If a shirt is the last thing standing between you and everything out there, the collar is at once a base need and an embellishment. It’s a punctuation mark on the essential. The collar is where the action is.

It used to be a separate ordeal from the shirt entirely. Collars came in stiffer fabric and attached to the rest of the body with buttons. It was constructed to withstand the needed intensity of everyday life: All that rub-rub-rubbing against the throat, picking up oils, picking up dirt. You could simply take the collar off and wash it separately. Or just replace it outright. It’s an eternally attractive thought, throwing away the most restrictive part of a thing when you’re tired of it. The outer edge, skimming the yoke and slithering over the shoulders, determines where things stand. Disappearing? A band collar is cloistered. Pulling out wide? A full spread is elite. Back when finely dressed men realized you didn’t have to hide the collar underneath folds of outerwear, Beau Brummell brought his out in dramatic fashion. He snaked the collar out of its hiding place in the coat and threw the points so high. The fabric, fully starched, would soar into the air and find its resting place on his cheeks. It wasn’t a comfortable setup, but it did establish a new paradigm, shifting underwear outside, shoving it into our faces (and his).

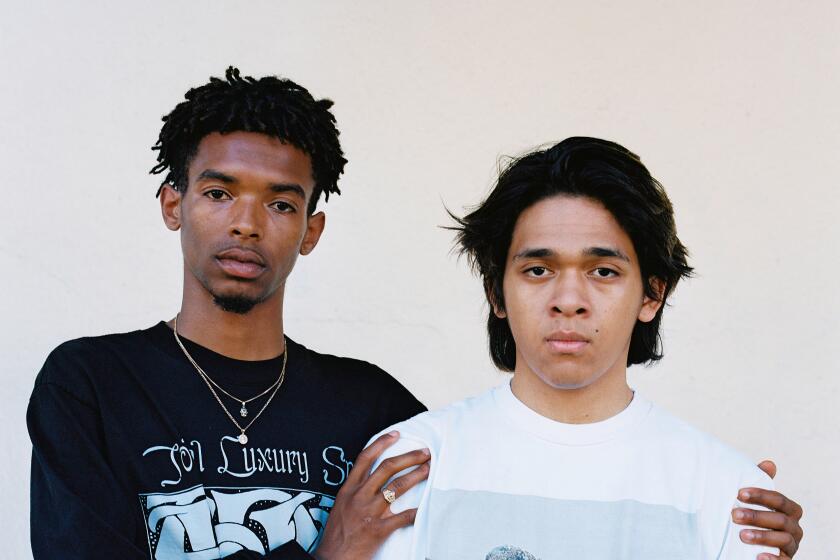

Daniel DeSure’s brand and the artist community behind it are pushing the possibilities of communicating through graphics on clothes.

Bend menswear’s dicta to your will like Thelonious Monk stretching time. What’s going on there is your business alone. Nobody’s paying you that much mind anyway. But there’s freedom in insignificance, of losing your stray thoughts and anxieties to the dance that fabric does against your skin, in the way your fingertips run over little details and doodads, in constructing an elaborate vocabulary largely spoken to yourself to describe small and private rituals and pleasures.

If you grab a shirt with your fists, grab it like it owes you — money, respect, a level of community standing granted at first sight — so you can notice all the different details and stitching at play. The panels of the body swan outward from the flesh and curve around the hips at the hem, once yearning for a high-waisted trouser to dive into. Pants ride lower and shirts cling tighter for want of a perch, but there’s something to be said for a loose shirt free to snatch a breeze on your behalf. I’ve seen all sorts of interventions here, like on the Kansai Yamamoto shirt I had once that brought in high slits and side-ties to make this staid expanse more theatrical. But it was doing too much; I got rid of it.

I find the world turbulent, so filled with terrors and tragedies I am unable to meaningfully address. If I’m going to resign myself to myopia, I want my navel-gazing to be well-decorated.

Amor Prohibido’s Bryan Escareño has a penchant for testing the limits of fashion. His gender neutral collection with Género Neutral investigates the capacity for clothing to hold court in the castle of high art.

When Jay-Z inflicted the going-out shirt upon us, what set his button-ups apart from their forbidden cousins — the tank top, the jersey and the T-shirt — was the placket. Its stripes and colors and accouterments allowed for the suggestion of a good time, but right out front were a series of interruptions. Diversions visually suppressed shiftlessness or illicitness, or anything a bouncer had been instructed to keep out of a club. The placket is a fascinating spot for distinction; it can barge out front, or slither against you à la française, or hide entirely. Jay-Z was getting old and seeking to project maturity. He succeeded — look at him now.

The thing about the collars that the Midwest bosses wear so well when we meet them in “Casino” is that they’re absurdly long. And not long in the ‘70s way, where they zoom out from the neck like a fighter jet — a trait that Raf Simons and Miuccia Prada took to a silly extreme in a recent Prada men’s collection — but long in a front-and-center business way. The points nearly preclude the tie knot, offering instead a slim strip of fabric peeking through a slit. It’s almost a parody of a white-collar collar, a perversion of a clergyman’s. Here are men who move heaven and earth to avoid a 9-to-5, and their cloistered throats say so loud and clear. That and all the blood spatter.

I prefer button-downs. They look great unbuttoned, without one of the ties I don’t know what to do with anymore. Plus, they’re a wonderful article for endlessly argued, meaningless differences. (Writer and critic Troy Patterson once wrote that philosophers of the button-down posit proper collar rolls like the wings of an angel, which is the kind of talk you get from people who think too hard about this kind of thing.) Brooks Brothers gets the credit for bringing them mainstream, meaning they stole the idea in the most commercially viable way. Polo players wore them to keep their collars from flapping in the horse-driven breeze, and soon the polo shirt was stilling oxford-cloth prep school collars facing no real threat of dislocation, from the winds of motion or change.

In the years since, the bend toward buttons has become a small branch of textile science. As technology sought new problems to solve, shirtmakers started treating the cotton so that you didn’t even need to starch it at the cleaner’s. But why stop there: They threw a liner into the mix, yielding a collar that’s chemically smooth and forcefully stiff. The lined button-down is an odd piece of equipment, a tiny monument to efficiency-minded dressing. The purists’ preferred, unlined collar is soft like a tiny boa. An affectation. A distraction.

Anti-efficiency is the territory of the obsessive, of people who notice these things, of people thankful to have a reason not to look you in the eye, of people who’d prefer to surmise the turmoil of your life through your decoration instead of facing the stuff that happens to a person sitting underneath the clothes.

Models: Shea Estrin and Hanna Yohannes

Makeup: Alexa Hernandez

Hair: Lola Benson

Styling Assistant: Raf Talaat

Location: FD Photo Studio

Melvin Backman is a writer and editor based in New York.