- Share via

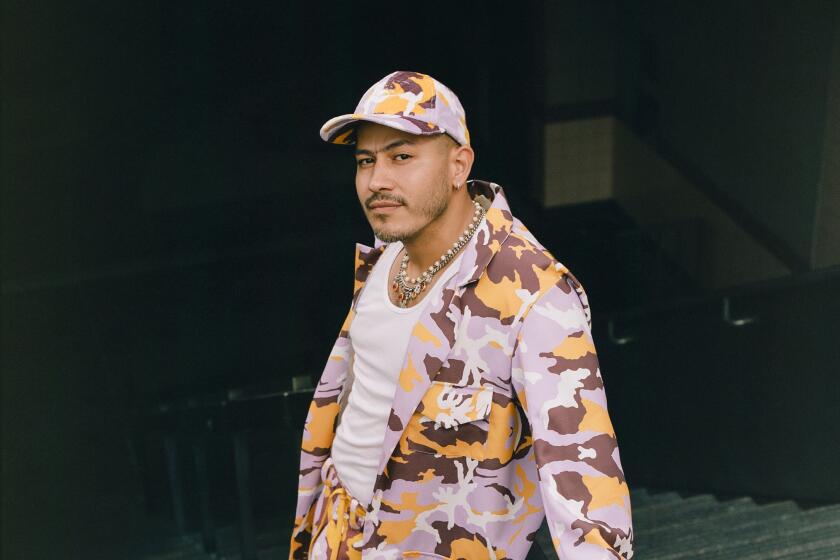

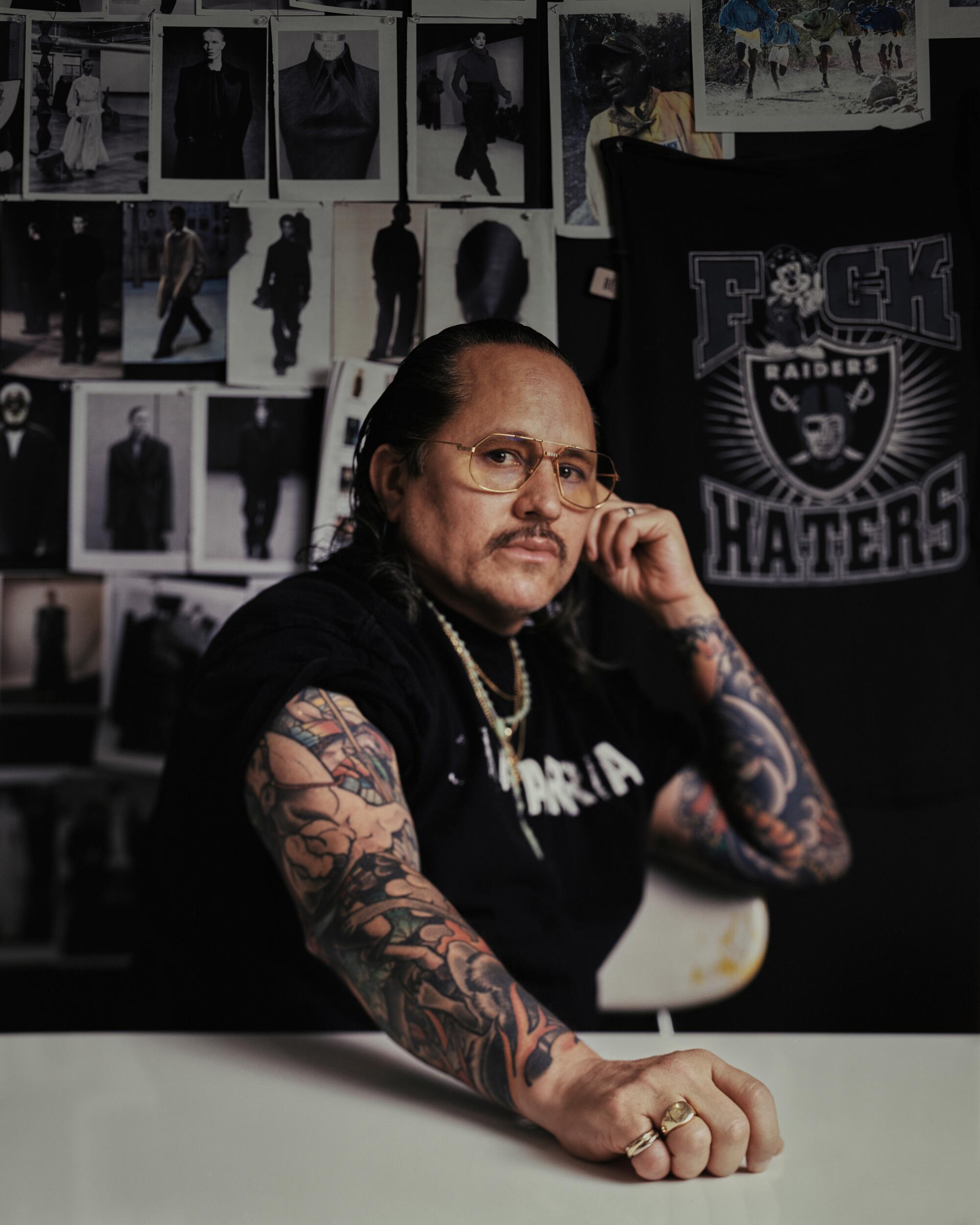

“No matter what I’m doing,” says Willy Chavarria one day over Zoom, “you’ll always know where I’m from, my influences and my culture.” It’s the social nature of clothes that keeps the California-born, Irish and Mexican American designer’s inspirations close to home. At his namesake label, the designer freaks classics like the T-shirt: dropped-shouldered USA crop tops turn the American flag upside down. This could be seen as a political act — but more than anything, Chavarria is showing us who he is. He’s not simply representing Latinidad; luckily, he’s letting us see into it. At the same time, his career has charted across the United States at brands like Joe Boxer, American Eagle and Ralph Lauren. And as of 2021, Chavarria has been the senior vice president of design at Calvin Klein. The dichotomy of his corporate reach and downtown appeal makes Chavarria a singular force in the fashion industry.

Last year, singer Moses Sumney accompanied Chavarria to the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) Awards. It was Chavarria’s first nomination for American Menswear Designer of the Year. Sumney wore a black silk suit with a large rosette on the shoulder right after it walked New York Fashion Week. “It’s all about form and beauty,” says Sumney. “Within that beauty, you’ll find what Willy is trying to say.” Both found the collaboration a perfect fit: “Willy and I both approach masculinity with an expansive point of view. I know we hear those words all the time, but it’s true, and we’re coming from a place where it’s not the norm.” Sumney spent his adolescence in Riverside among the Chicano culture Chavarria often references in his collections.

Rio Uribe is closing the book on his 10-year-old brand at NYFW. But the GS legacy — flying your freak flag on your back and riding for your community through your clothes — lives on.

In “Eve’s Hollywood” (1974), Eve Babitz spends a chapter on the Choke, a 1950s pachuco version of the jitterbug she witnessed at high school dance competitions. Babitz saw the popular Mexican dance as “enraged anarchy posed in mythical classicism as a dance.” It “was so abandoned in elegance it made you limp with envy.” Or perhaps what she saw can be called dignity, the kind Chavarria describes in the interview below — enjoying your beauty and sharing it on your terms. After all, it’s not Eve’s Hollywood. California belongs to Mexicans, no matter how large that white Hollywood sign looms. Every shape, cut and textile Willy Chavarria sends down the runway walks with the assurance of being home.

Devan Díaz: You’re from California and have spent time in Europe. Why do you show in New York?

Willy Chavarria: The ferocity of people in New York, just while going about their day, is beautiful. It’s rough here. [In] New York, people show themselves. It’s so hectic we don’t have time not to be ourselves. It’s like that Jenny Holzer quote: “Spit all over someone with a mouthful of milk if you want to find out something about their personality fast.” Also, the fashion industry is based here, and I like to use the city as a backdrop to show that I’m one of the top American brands. But we’ll definitely put on a show in Los Angeles one day. I’m rooted in California. If I get too far from the sun of that state, I begin to struggle. I’m like a vegetable growing from soil. I’ll never be without it.

DD: The fall collection felt like a foot off the street toward elegance. What was on your mind?

WV: As I’ve grown, I’ve wanted to show myself that I can play on a top-tier level of luxury. There aren’t a lot of brown people playing at that level. But I will always find a way to include sportswear. I will always make sure that I can offer that, and I will always make sure that I find a way to have price points that will allow anybody to get a piece of Willy. I can sell $40 T-shirts for people who don’t know who I am but resonate with the message. And then, you know, $500 T-shirts for people who can afford luxury quality and want to wear designer apparel. I protect both of those things because it’s essential for me not to be exclusive.

Marcus Correa knows fashion doesn’t mean anything without the specific stories that people bring with them.

DD: How did you develop that protection?

WC: It comes from the gratitude I feel for how I grew up. I am not jaded in any way, and I appreciate luxury. Being around working people taught me how to have a work ethic, enabling me to grow myself and my business. I’ve had to work for everything I have, which has made me see America through a grounded lens. I’ve always understood what this country is all about. My parents were involved in the civil rights movement and ensured I knew what was happening. When you don’t have a lot, you make the best of what you have. So your essentials become what you wear to display your beauty or strength. Making those essential items into luxury translated well into fashion design.

DD: Like the T-shirt.

WC: For me, the ultimate elegance is a pressed T-shirt, khakis with a black belt and white sneakers. So clean, so pure, and it works on everybody.

DD: At Calvin Klein, those essentials are crucial.

WC: Calvin Klein was always one of my biggest childhood influences. It got me into fashion because I always saw its effect on culture. When the CK One campaign emerged in the ’90s, they said this is who we are, a gender-inclusive fragrance for everyone. The images were incredibly diverse for their time. Seeing how fashion can positively influence culture drew me in. So, when I started working for Calvin, I had that in mind. My most important role in this position is to have a positive influence on culture.

DD: How does that figure into casting at your own label?

Since its inception over a decade ago, the brand has steered the conversation about clothes with unmatched inventiveness by continuing to experiment with any given guardrails.

WC: Latinx culture often gets boiled down to a lowrider or a taco stand within our current media machines. When my brand first started, there were more literal moments. I have a collaboration coming up with FB County, which has yet to be released, but it’s a Chicano gang-related brand of clothing. But there’s more out there. I want to show the entire Latinidad that we’re beautiful. I’ve ensured that our team reflects that. As long as we maintain that sincerity, we won’t be at risk of commercializing our culture. We’re showcasing our beauty on a higher fashion level, but we’re always conscious of how we connect with people, share culture, and give respect and dignity to the source material.

DD: What do you mean by “dignity”?

WC: It’s being shown in a way that is respected. It doesn’t mean someone who is incredibly sexy — it’s not that form of dignity. It’s the truest form of appreciation for what that person is. It’s about wearing clothes that make you feel good. It’s feeling empowered and having a relationship with the greater good. It’s about feeling as beautiful as you are.

Chavarria blouse, belts and hats. (Paul Yem / For The Times)

DD: Are baggy, wide silhouettes most often adopted by the young and restless?

WC: I’ve always felt that oversized silhouettes have been a part of our culture because taking up space says: Here I am to be recognized. It says I am part of the same world you are, especially for people whose land was taken from them through colonization. The idea of your clothes taking space back really has a rebellious side. You can track the evolution of these shapes back to the 1940s and ’50s pachuco down to the cholos of the present day. It’s all about showing your presence.

DD: You find new shades of masculinity in your designs every season. Why is that?

WC: Well, there’s no way around our issues with masculinity in Latinx culture. But I’ve always believed that masculinity isn’t always toxic. There’s toxic masculinity, but I’ve always believed in showing and toying with masculinity’s loving side. I often think about Tom of Finland’s hypermasculinity mixed with femininity. I have a lot of nonqueer, masculine people on my team and in my network that are just down-ass fools. They’re not toxically masculine, and they exist. It’s OK for some straight people to be cisgender. [Laughs]

DD: You’ve offered some of the most viable skirt options in menswear. In your opinion, what will it take for skirts to become a mainstream clothing item for men?

WC: We’re in this transition period with our wardrobes right now. The only hold-up is the old fashion institution. Every fashion business has gender in play. There’s a men’s buyer and a women’s buyer. There’s a men’s designer and a women’s designer. There are gendered pattern makers. It’s deeply rooted in the industry and needs to change along with the culture. We’re on our way there, and it’ll change faster than we think. Men will wear skirts when it’s all one shopping experience and it stops being separated by gender. No matter how you identify, your existence must have sensuality. Keeping your teeth clean and bathing daily is good for your mental health. We mustn’t deny ourselves that in our wardrobe.

Devan Díaz is a writer from Jackson Heights, NY.