- Share via

At first glance, Sable Elyse Smith’s “A Clockwork” (2021) looks like it was transported from an amusement park. The black metal structure resembles a rotating Ferris wheel, its motion slow and seemingly unending. But the octagons and poles forming this sculpture were sourced from aluminum tables and seats used in prison visiting rooms. Items that are usually bolted to the floor, restricting a person’s movement, become kinetic.

In her first solo exhibition at Regen Projects, “FAIR GROUNDS,” Smith expands upon “A Clockwork,” first shown in the 2022 Whitney Biennial. Drawing on the sights and sounds and language of the fair, she collapses the carnival and the prison, revealing how deeply intertwined punishment is with entertainment and spectacle. Furniture is transformed into large-scale jack-like objects and colors evoke the flash of police spotlights. The show is partly inspired by the writings of scholar Christina Sharpe, who, in her book “In the Wake: Blackness and Being,” characterizes anti-Blackness as an atmosphere, or “weather,” that coats everything in the U.S. Smith expands on this idea and positions the carceral system as a similar kind of atmosphere. For her, prison isn’t a location but a state of being.

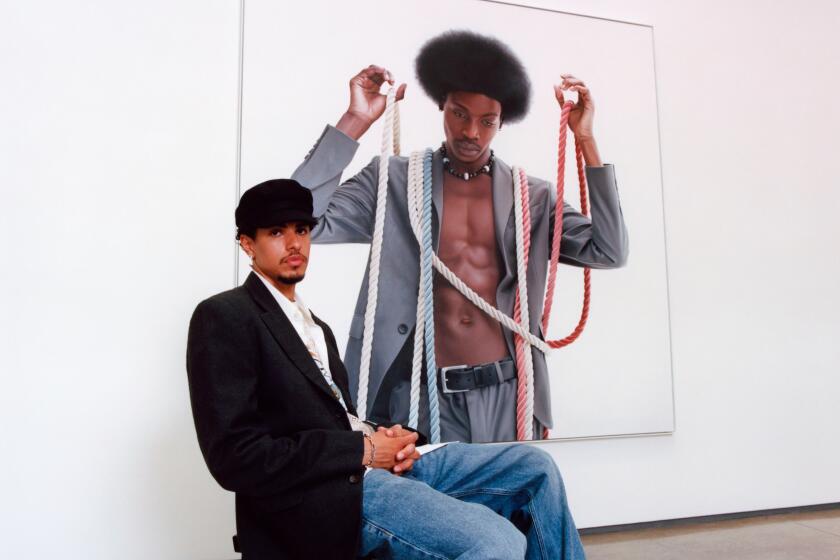

L.A. artist Delfin Finley explores the gray areas of living, where joy and pain collide.

Across her videos, sculptures, photographs, works on paper and texts, Smith returns to how society is shaped by carceral logic. The artist, who has now lived in New York for more than a decade, was born and raised in Los Angeles, and her work draws from her firsthand experience interfacing with the prison system in Southern California, where her father was incarcerated for 19 years. Her work unpacks the psychic toll of navigating these environments daily. At Regen Projects, Smith reimagines the visiting-room stools of prisons as playground toys. Like a toss of the jacks into the air, incarceration feels like a game of violent chance, where the rules are driven by larger histories of racial capitalism.

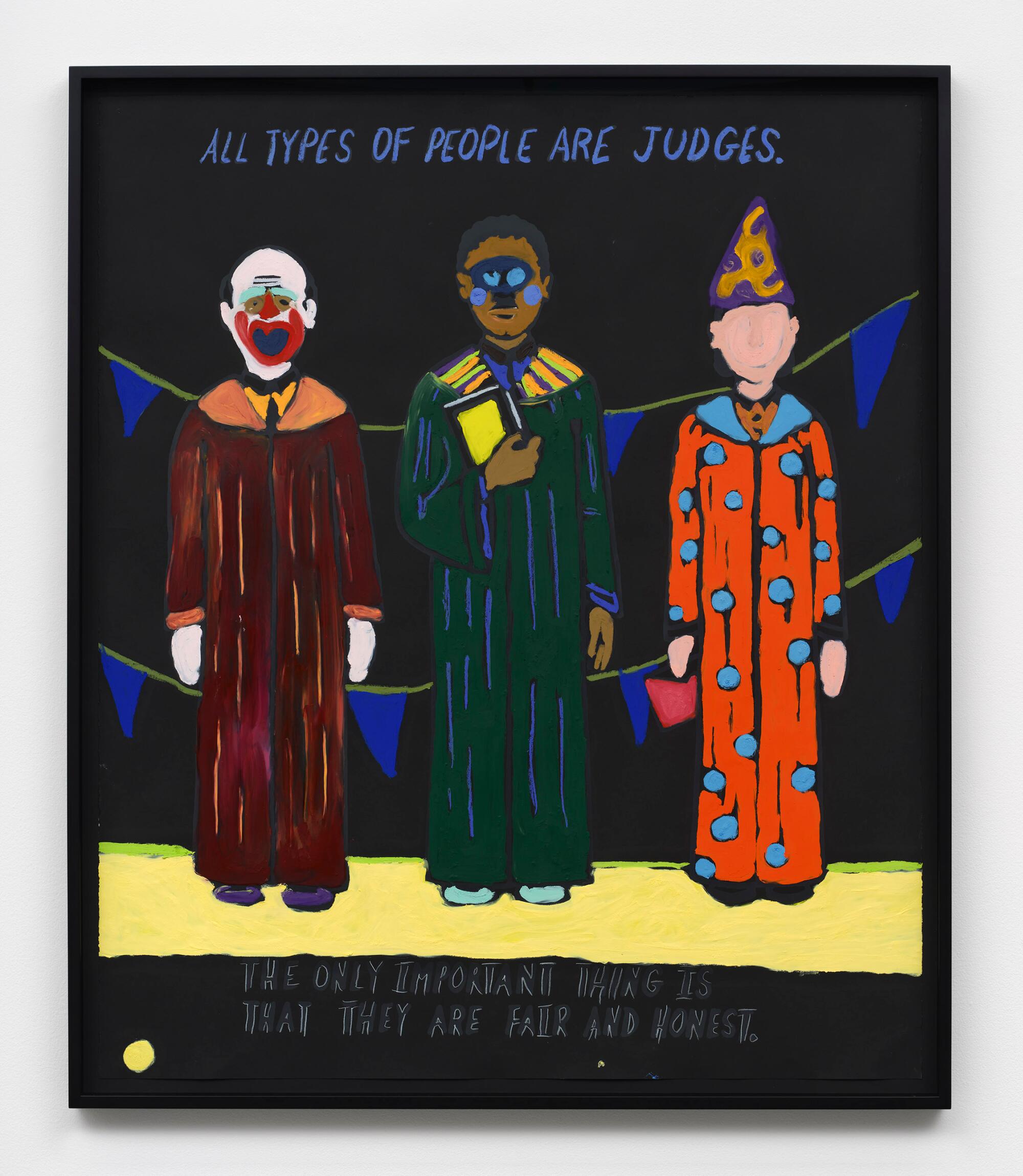

Elsewhere, paintings like “Coloring Book 139” recast the pages of a children’s activity book — which Smith found years ago while taking a walk in her Harlem neighborhood — into cutting satiric scenes that emphasize the absurdity of incarceration. Though the original pages exude a sincere trust in the court (“People Have to See The Judge When They Break the Law,” the text in one painting reads), Smith adds her own oblique commentary, using oil pastels to turn figures into clowns and wizards. In Smith’s hands, images of justice and safety warp into a carnival of faceless judges and rigged games.

Allison Noelle Conner: Most people associate you with New York, but you were born and raised in Los Angeles. How did this city shape you as an artist and thinker?

Sable Elyse Smith: There’s a lot of indirect references to how L.A. has impacted my creative practice. Music is a big influence in my work, even if it isn’t obvious on the surface. Specifically, rap music, and definitely a lot of West Coast rap music. I used to make music when I was in high school, and for a couple years out of high school. There’s something about the rhythm, the imagery and the aesthetic that sonically exists in L.A., West Coast, gangsta rap — that aesthetic drives everything that I do.

ANC: Sampling, remixing. Those all exist in your work.

SES: Exactly. Also, a lot of my work is thinking about the carceral space more broadly, so not just prisons. My first experiences of police and prisons were in California — those are most of the prisons that I’ve actually been in and visited. That’s the impetus of my practice — those experiences and thinking about those architectures and those landscapes, like leaving L.A. and having to drive to these other locations through these vast desert landscapes.

Then there’s all the material references. Different kinds of jails or prisons have different aesthetics, different colors, different kinds of rules. That’s the kind of material I’m pulling from to make the work.

With work that spans performance and video but remains rooted in photography, Lennon functions as part conductor, part witness. In this photo essay, Naima Green accompanies the artist on her morning spiritual to Kenneth Hahn Park and back to the studio.

ANC: You mentioned in other interviews how you’re less interested in representing prison as it is and more driven by affect, or how it feels to be in these spaces. Could you say more about that?

SES: Emotion is the knowledge that we all have access to. There’s no hierarchy in how you feel. You can respond to things on a bodily, haptic level. The art world is all about elitist intellectualism — it’s a gross generalization, but it is true. There are these hierarchies in many ways. Even though I think anyone can have an experience with any kind of artwork, there are a lot of different barriers between how they might access it, which can lead people to be closed off to what their experience might be. Feeling is one way in.

ANC: You often incorporate words into your artworks. What animates your approach to text?

SES: I would say music, but also voice, vocalization, sounds. I’m creating sentences because of their sonic qualities, in addition to their meanings. The sound drives me; I guess I’m looking for something in that. Also, it’s fascinating to think about language as a system that can be used and deployed in all these different ways. The word has a meaning, but its meaning can shift in the way that it’s said or screamed or uttered, by the intonation that you use, the inflection. There’s lots of information that we can gather from that. But it’s used to oppress or judge or inflict violence in different ways.

ANC: Your work seems to point us to the other meanings hidden in a word or image.

SES: Even if you show an image of something that happens that isn’t 100% the same thing. It’s a snapshot of something that’s standing in for the thing. But there’s all this invisible s— that happens around it that we cannot capture. That’s more real to me. I’m interested in things that are a little bit more complicated, a little bit more nuanced — something that is true to how I experience the world, how I think most of us experience the world. I try to highlight that and center the things that we rely on. [A] picture is also created. It’s created from someone’s point of view. It’s unstable in its truth in that way.

ANC: How did “FAIR GROUNDS” come to be?

SES: Sometimes I get fixated on sites, because they feel like a nice starting point for the foundations to locate an audience. I was thinking a lot about this kind of carnival, this fairground space, and thinking about the aesthetics of it. That’s the first thing that drew me to it. And then, doing the research and just thinking about: OK, what is the language that exists in that space? What are the games? What is thrill? What is risk? And how [has that] shifted over time?

The Surrealist blues poet is a musician of the subversive imagination, a truth-telling magician. Her poems are powerful and dangerous, like violets pushing through concrete to kiss the sun.

ANC: What else attracted you to this idea of the fair?

SES: A carnival is a space where violence in the past has been permissible — think about freak shows. People who are different are put on display. There’s a kind of economy around that. Then, the public or the community comes, and for some reason, because they’ve crossed the bridge, and chosen this architecture that’s labeled as a place of fun and amusement and enjoyment, it’s OK to do “x-y-z” thing. But once you leave that area, then there are different rules of morality. I’m always fascinated by what society does to allow themselves to do whatever to transgress.

ANC: Could you talk about Christina Sharpe’s writing on “the weather” and how that influenced your thinking around this show?

SES: It’s funny, because I feel like I probably came across that particular book, “In the Wake: On Blackness and Being,” late. That one chapter on the weather [thinks] about anti-Blackness as a kind of climate condition, not just, “Here are these historical events that happened and here’s the domino trickle-down effect.” It’s like no, everything that exists, all of these houses that are here, the grocery stores, everything is touched by [the weather]. That was the first time that I have read something, especially some theory, that directly connected to the way that I have been thinking about the world.

ANC: For you, how is the prison related to the weather?

SES: A lot of my life has been touched by and affected by prison, by these kinds of structures. In my mind, those two words could be interchangeable. We have created this image of prison as an architecture, as a destination. But structures of policing are everywhere.

ANC: For “Barricade” (2023), you remade the stools in prison visiting rooms into these colorful toy-like objects. Though a lot is said about the materials you use, I’d love to know more about your approach to color.

Poet Christopher Soto unpacks how the history of policing has shaped and scarred the urban fabric of Los Angeles.

SES: When I made the first work from this series, I initially started with this pale blue color story, because it directly referenced real furniture in an institution that I visited. After a number of them had been made, I started to think more about the context. Color could be shifted to signal something else, whether that be a different affect or something else conceptually. Shifting the shape also does that.

For this show, there’s a painted motif on the wall in one of the rooms that transforms the viewing experience. It’s a nice reference to this carnival world. Two sculptures are a riff on that wall motif, but they also reference those generators [that the police use] to power spotlights. I used to live in Harlem, and I would see them on every other corner all the time. [The generators are] this cream, black and blue color. I just color matched the cream and black in degrees. [The sculptures] reference that spotlight but also abstract it.

ANC: Ever since 2018, you’ve used coloring books as a form to explore the absurdity of carceral logic. Why do you find this form so generative?

SES: I feel like there still is some potential [that] I haven’t necessarily exhausted. Conceptually, the system itself is insistent. The fact that these things persist and keep developing and repeating themselves, kind of replicating the next generation of them, makes sense to me. Also, each page has a different narrative, and a different affect, and a different theme that it’s pointing to, and then a different thing that I’m pointing to in it. There’s still a lot of possibility. If I juxtapose a page with another page, that creates this entirely new narrative. I’m still interested in all of those configurations.