- Share via

This story is part of “Clearance,” a design issue that peels back the layers of aspirational architecture in L.A., and envisions a more beautiful future that lives a little less on the nose. Read the whole issue here.

I came of age in Brasília, which is such a specific city — it’s a planned city by the architect Oscar Niemeyer and the urban planner Lúcio Costa, and they were very much interested in Le Corbusier’s Modernist ideals. The urban plan follows the Cartesian shape of an airplane. As a young girl, I was at first a little troubled and scared, not knowing how to navigate that place, but then I was really mesmerized by how beautiful some buildings were. Because I grew up there, it’s home — you start having a different relationship with the space because it’s the place that you live in.

I think what that experience did in terms of how it influenced my work later as an artist is that I’ve always been very sensitive to the space around me. I became very accustomed to hyperanalyzing visually and physically what is around me, because it was such a powerful and strong experience that I had at an early age.

I explore ideas of place in my work — it’s always about deconstructing ideas of place or questioning how we define a place. Mapping, which is present throughout my work, is one way of doing that. A map is a representation of a place, and, as any form of representation, it’s very biased in what you decide to include.

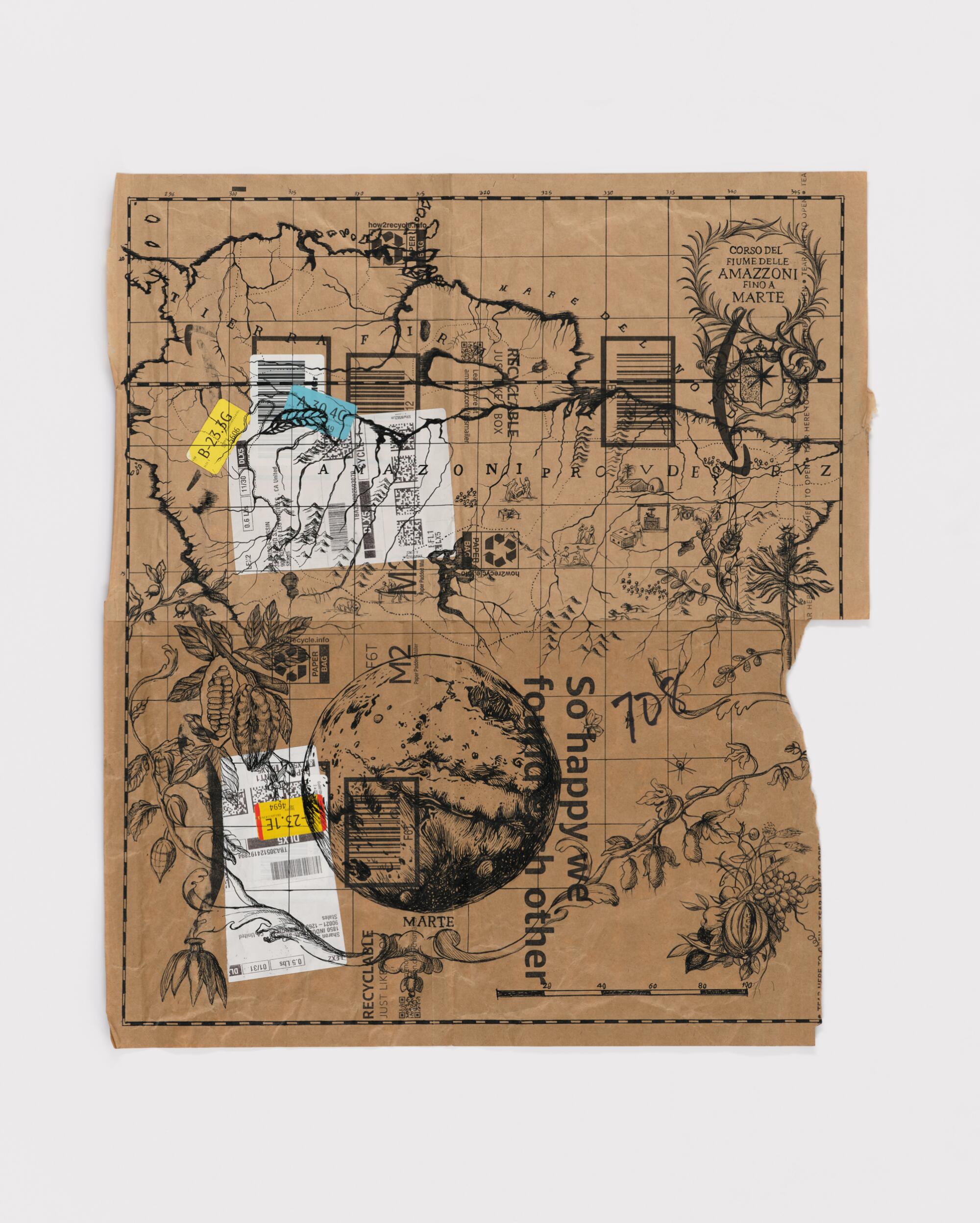

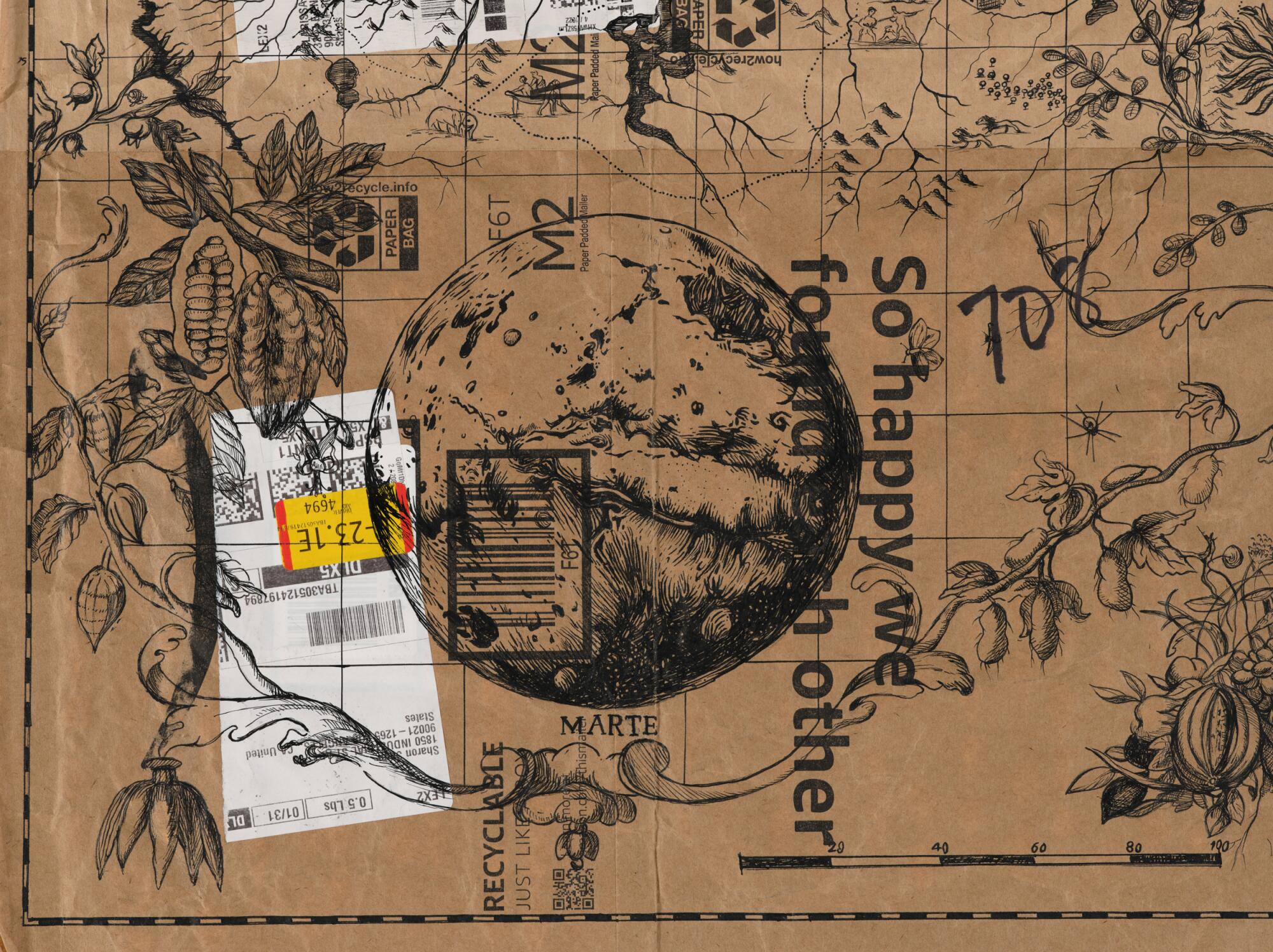

In this new series, I’m using Amazon envelopes and drawing maps on them. I started using Amazon packaging because I was interested in the relationship between the word Amazon for the e-retail store and Amazon for the forest — if you say “Amazon” today in the U.S., people will think about amazon.com and not the forest. I was also interested in how Amazon packaging — the ubiquitous remains of consumer society — stands for extractive cycles of production and consumption, which ultimately impact our environment.

I’ve been looking at Portolan charts, the European navigation maps from the 1500s and 1600s. The excessive colonial drive toward the environment started in that period. I wanted to connect these maps that were used to define the land masses of the globe that we have today — all the world atlases and maps were created from that period — and equate them with 21st century space exploration. There is a narrative in the media that space exploration will help us resolve problems on planet Earth. The thought behind 21st century space exploration seems very focused on extracting resources from other celestial bodies, which replicates the European navigation era that was all about getting to other places where you could find resources to bring back to Europe, be it people or gold or something else.

The map featured here is called “From the Amazon River to Mars,” but in Italian (“Corso del Fiume delle Amazzoni fino a Marte”). I research and find maps that are real Portolan charts and I start my drawings from them, so there is a little bit of transferring sections of actual Portolan charts. The one that I have is an early Italian map of the Amazon basin, so I just took the actual title of the map. I put a drawing of Mars at the bottom, so you have what looks like the Amazon River that leads to Mars. We navigated the globe first, and now we’re going beyond that — but with the same erroneous, extractive colonial mentality. I also pulled from another map of the Amazon that had some plants that are native from that area, and I like how they combine with Mars, that it’s this surreal place. Scientists believe that there was water there at some point, which could have enabled life similar to planet Earth. So I think it also plays out this desire to find life as we know it on Earth in other planets, in other places, but equating that with all the problematics of the European navigation era of the 15-1600s.