- Share via

This story is part of Image Issue 14, “Elevation,” where we examine beauty as a state of being, a process of realization. Read the whole issue here.

Arima Ederra is the type of artist who is intentional about what she puts out there. But for the release of her new album, “An Orange Colored Day,” the L.A.-based artist is choosing to pull back the curtain a bit.

“I’m truly a big kid at heart,” she says, a smile blooming. “Children are the untainted adult, you know?”

Sitting in the shade near a brilliant bougainvillea in the backyard of Teo Halm, one of her producers and collaborators, I can’t help but agree. Ederra’s voice is patient, considered and dulcet. Her demeanor is neither rushed nor expectant, her music like an open, extended palm.

Ederra has been in L.A. for about six years — she grew up in Las Vegas once her parents, both Ethiopian refugees, settled there to raise a family. In her time here, she’s built a dedicated following. Her deceptively simple writing style and layered vocals blend with her East African sonic roots to create intriguing music that feels like a gentle rub on the back. Supportive and attentive.

Her sources of inspiration connect clearly to her art and principles: bell hooks (for her embodiment of love), Lauryn Hill (for her lyrical poise), Bob Marley (for his holistic presentation) and astrology (for its foundation in understanding).

Tackling grief, personal loss and her own childhood, “An Orange Colored Day” delves into Ederra’s past. She finds levity channeling the wealth in juvenile wisdom: Let go, be honest, be happy.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Nereya Otieno: What does your name mean? African names usually come with a story.

Arima Ederra: It’s actually not Ethiopian — everyone always thinks it is. One day, when I was in high school, I decided I wanted an artist’s name. I’ve always been fascinated by jazz singers or authors who gave themselves aliases. Me and my best friend were really into linguistics and she came across the Basque language and I asked her to describe me in two words. She said, “beautiful soul.” So I looked it up and “arima” means soul, and “ederra” means beautiful. So it means “soul beautiful.”

NO: Wow! I’m glad I asked. So what’s your story with music? How did you come to it?

AE: I actually don’t come from a “technically” musical family, but music was always pouring out of our house. My dad was a taxi driver and would work from anywhere from noon till midnight. I would wake up and hear Ethiopian music or jazz or some Afro rock playing really loud and that was how I knew he was home. He was also friends with a lot of Ethiopian singers, and our house kind of became a hotel. Me and my little brother were forced to share a room because our third room was always for whichever artist we were housing at the time.

How the 21-year-old artist figured out the secret to life.

NO: Just being surrounded by music made you pursue it as a career?

AE: I would say I was a writer before I was a singer. I wrote poetry a lot as a kid. At 19, I started an open mic night in Vegas because I felt like there was no place for local artists to express themselves in such an entertainment city. There I learned that I liked performing. I would sing and people would ask where they could listen to my music. But I didn’t have any music, I only had covers and nothing was recorded. So then I decided to get a bunch of beats off SoundCloud and freestyle to them, sing to them or write to them. It was a way for me to turn the poems I wrote into a song.

NO: And then you just ran with it?

AE: No. [laughs] I think I toyed with the idea of pursuing music, but as an immigrant kid, I feel like there’s always a lot of pressure to pursue something that’s more stable. My parents were supportive in certain ways, but they were like, “Yeah, that’s cute and all, but go to school.” So I went. But then my father got sick and I left school to help while he was transitioning. It wasn’t until he passed that I thought, “OK, this life thing is really, really short.” So I decided not to do anything I’m not called to do. I dropped out, moved to L.A. and put together a collection of songs and ideas. That was an EP I put out in 2016 called “Temporary Fixes.”

NO: Fans have been waiting from that EP to this album. At what point did “An Orange Colored Day” start to feel more like a body of work?

AE: After “Temporary Fixes,” I took time off to explore. I was still processing so much. I think the first song that I wrote was “Free Again.” I had been introduced to Jon Bap by a friend. He was a fan and I was a fan. We emailed a bit, spoke on the phone and then he sent me those instrumentals. That sparked it. The song was actually kind of inspired by a day in the park with my best friends.

NO: Tell me more.

AE: It was three close friends and all four of us had lost a parent we were really close to. There was this surreal moment when we were all in a tree together. It was extremely beautiful and cinematic and there was this gorgeous orange meadow because the sun was setting. After we had all been crying, talking and sitting in silence, I watched two friends who had lost their mother jump off this tree and run into the meadow together. I felt so connected to that moment. And then I jumped too.

NO: That sounds incredibly special. Did the rest come quickly after that?

AE: I felt very much like an open channel and was constantly recording voice notes of ideas. Eventually I told Jon I had a few songs that I thought would be cool to produce with him. We worked on it for quite a bit and then we took a pause. A friend of mine passed and I got evicted from my apartment because of gentrification — they were building the stadium in Inglewood. It was all very hard, but I took that as an opportunity to take a break from everything. Grieve and write.

When I came back, I had a new perspective on what I wanted the album to be. My friend Michael Uzowuru introduced me to Teo Halm. Me and Teo just hit it off. I felt such a musical connection to him and we continued to work on the album together and made new songs.

The queer, Latinx songstress San Cha tells Suzy Exposito how she achieved enlightenment by learning to create art from a divine place.

NO: We’re in Teo’s backyard now; his studio’s here too. What did this place add to the album?

AE: As you saw when you came in, his family is so warm and loving and so is Teo. This is like a home to me. It’s very comforting. And Teo helped me turn ideas into a full piece of music.

I always think of this Erykah Badu line where she says, “What good do your words do if they can’t understand you?” I feel like a big influence that I have in the musicians that I love is just how much they can reach you through the music they make. I’ve always wanted to be able to reach a lot of people with the words I’ve been given to share. So this space has really been a beautiful environment for me to feel safe enough to expand myself.

NO: There’s such a childlike logic throughout the album, but about big concepts. It makes sense that it was being written in an actual family home.

AE: That’s the other thing about this place and my dynamic with Teo and Jon at that time: We were having fun. I took really serious things and made them light. I’m just truly a big kid at heart. Children are the untainted adult, you know? We’re all really kids on the inside. The world just adds all these patches of experiences and makes this quilt of a person. But you can see a kid say something so mean to someone and then, two seconds later, the child is forgiving that person. That, to me, is true humanity. The album is really me observing my childhood.

NO: I feel like this album is full of invitations: to sit, confess, play, listen. Are those directed at the audience or things you’re saying to yourself?

AE: I just got goosebumps because I’m like, “What am I going to answer?” [laughs] I feel like, a lot of times, I talk to myself as if I’m talking to someone else. With “Drugz,” I was broke and literally spent my last $50 on getting a bouquet of roses for my mom because it was her birthday and Valentine’s Day. And I just broke down in my apartment. Then I wrote: “I can’t buy drugs. I spent my money on my mama.” But the lyrics shift to say: You don’t have to worry about it, it will come to you. Writing sparks something in me when I can relate to that person. So, yes, I am speaking to myself, but knowing that someone else will hear and know what I mean.

More stories from Elevation

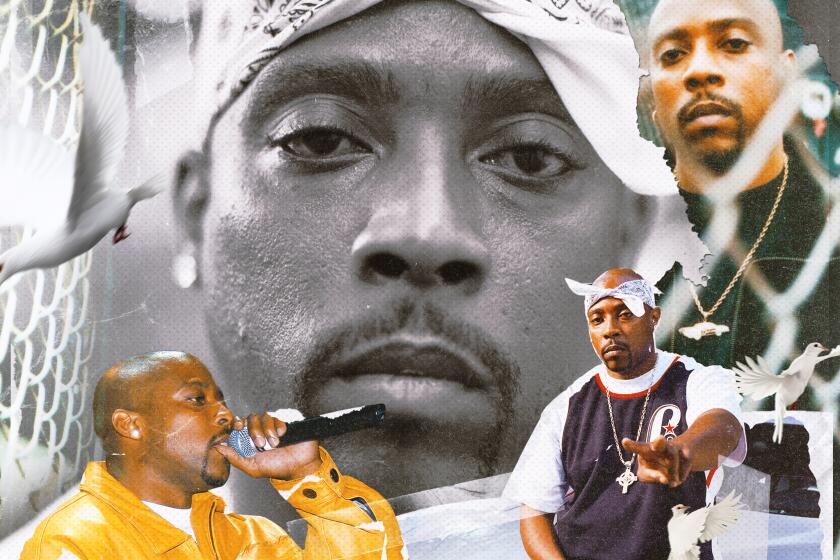

Jason Parham revisits the Smokey Robinson of hip-hop, Nate Dogg

Rikkí Wright unpacks the beauty routine as a metaphor

Rembert Browne comes of age without a hairline

Devan Díaz takes on tweezing as self-care in our warped times

Dave Schilling investigates why the mullet is the haircut that refuses to die

The state of L.A. beauty in one zine

NO: What does listening mean to you in relation to your work?

AE: I feel like listening is truly an art form. And I think it is a skill that I’ve developed over time. But for me, listening is just presence — like how present you can be with yourself, with your friends, with your family, with the thing that you’re pouring yourself into. With “Message,” I say, “Wait for it, it’s coming. But when it gets here, like are you actually gonna listen?” Little messages always come to us, but I don’t feel like we always listen to them. I believe that lessons continue to repeat themselves until one actually learns.

I just want to be a vessel. Truly, that’s something I always wanted as a kid. I just want to be a vessel to help people. And by helping others, I’m really helping myself. That starts with listening. Lauryn Hill, what’d she say? “Music is supposed to inspire. But how come we ain’t getting no higher?” And I think that’s true.

NO: What about the music aside from the lyrics? What was the thought process?

AE: A lot of the songs start off as simple voice notes. I think my collaborators and I took that simplicity and built textures on top of it. But I also think my upbringing is the human influence in the music. There are odd time signatures, which is in a lot of the East and North African music I grew up listening to. I always strive to make music that sounds like the things that inspired me and find a way to make it my own.

NO: It’s helpful to think of the world in which your conception of your sound sits. How does L.A. impact your work? The song “An Orange Colored Day,” for instance …

AE: That is so interesting that you asked about that song in relation to L.A. When I first moved here, I was a nanny for a very sweet family in Venice. “Orange Colored Day” was sadly written around a bunch of fires, but I witnessed the most beautiful orange sunset I’ve ever seen in my life. It was straight out of a f—ing animé or something. But I remembered my friend telling me the history of Venice and how it used to be mostly Black but then white people moved in and Black people got kicked out. So the song is about Venice as this mecca of Black people in this beautiful beach town who are no longer here.

But to answer about L.A., Vegas didn’t have the outlet that I needed to express myself, or maybe I felt like I had outgrown it. L.A. was a place for me to expand and grow into the artist that I’ve always known I was. It gave me the air to embrace who I am.

Nereya Otieno is a writer focused on intercultural spaces and the ways music, food and the arts are forms of storytelling. She lives in Los Angeles, where she pens Tasting. Notes., a monthly newsletter that pairs music and recipes. @felonious_punk

More stories from Image