Feeling America’s promise and perseverance on a trip to Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty

- Share via

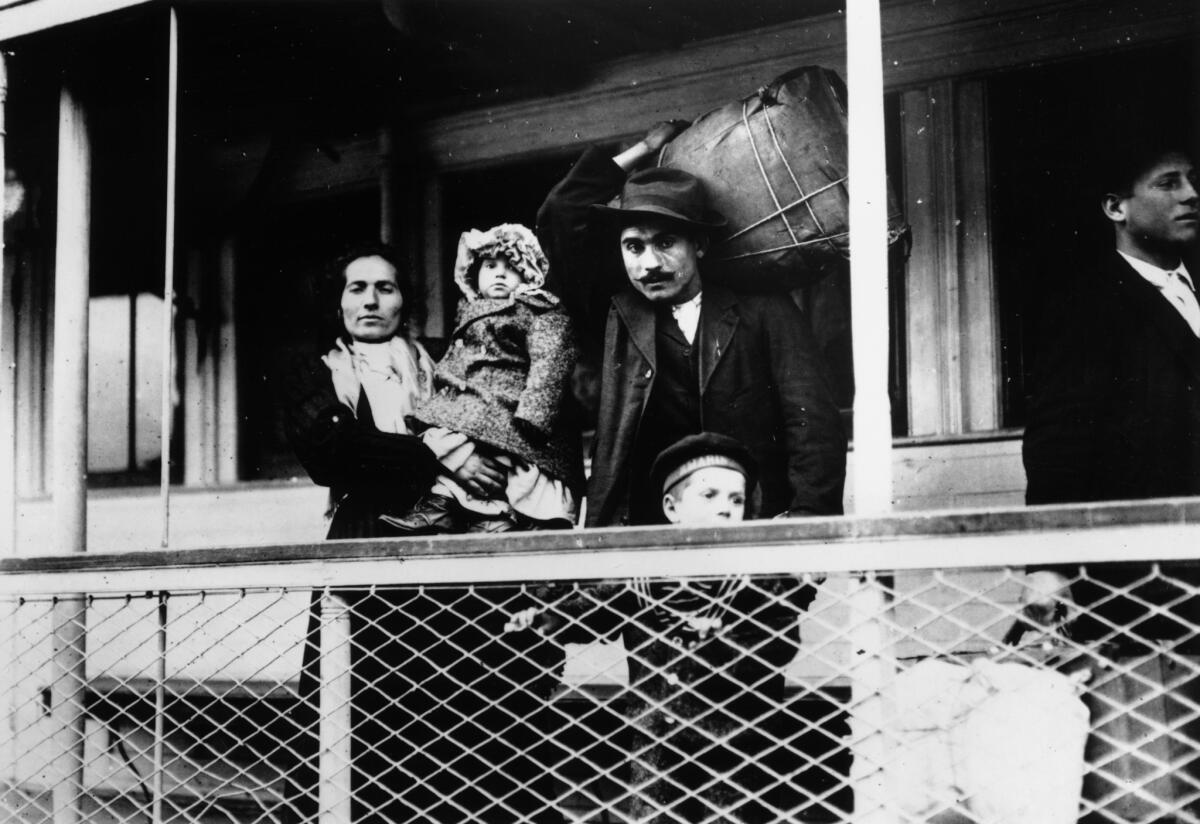

If you’re a white guy on a tourist ferry in New York Harbor, and the Statue of Liberty looms above, it’s easy to see her as the foremost symbol of immigration in the U.S., perhaps in the world. You look at her face, then you glance at the ferry’s next stop — Ellis Island, where more than 12 million European immigrants arrived between 1892 and 1924.

Without those huddled incoming masses and their sons and daughters, the U.S. wouldn’t be what it is.

But every year this immigrant history and America’s population drift a little farther apart. These days, about seven Latin Americans and Asians become U.S. citizens for every one European. If you do a Google image search for “immigration symbol,” you’ll see the Southern California running-family freeway sign two or three times before the first Lady Liberty.

Series: Celebrating our national parks »

But the easiest, most rewarding way to see what’s happening with immigration — and remind yourself about what was happening 100 years ago – may be to get off the ferry at Ellis Island and step into the first big brick building you see.

That’s the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration, expanded last year to look more broadly at “the peopling of America.” The new wing examines immigration since federal officials declared Ellis Island surplus property in 1954. The museum added the “national” to its name last year too.

“People were saying, ‘This is a great museum, but my story is not told here,’” said Peg Zitko, executive vice president of the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, which raised $20 million to pay for the museum revamp. “We’re really finally telling the entire story.… There’s really no other museum in America that does that.”

These are challenging stories to tell. And as national park units go, Ellis Island is in its infancy. Although the Statue of Liberty National Monument has been run by the National Park Service since 1933, Ellis Island was added to the monument only in 1965. At that point it was a ghostly, deeply deteriorated landscape.

For years, few tourists were allowed. Even now, much of the 27½-acre island is off-limits unless you sign on for one of the Save Ellis Island organization’s hard-hat tours of unrestored buildings, including the infectious and contagious disease ward; the kitchen; and the mortuary and autopsy room.

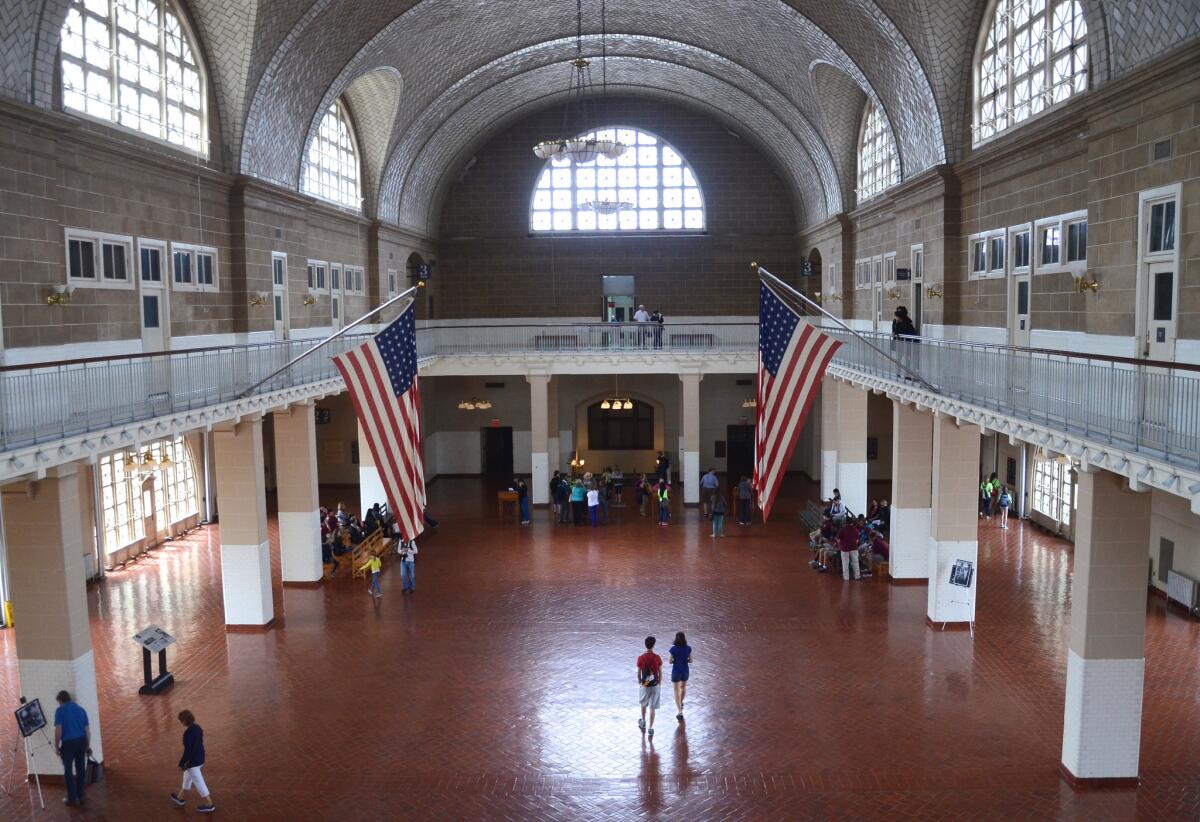

Most visitors, however, head for the island’s stately, red-brick Main Building, built in 1900, then reborn as a museum in 1990.

On the way in, I did hear one mom warn her young child that “this is not as glamorous as the Statue of Liberty.” But I also met Robert and Lisa Marie Spillane of Aylesbury, England, who had planned to spend three hours at the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. Instead, absorbed by the stories of trauma and triumph, they’d spent seven.

“Wall Street and the Museum of American Finance will have to wait,” said Robert.

Inside the Main Building, visitors work their way through dozens of galleries filled with historic photos — many larger-than-life faces with disarming stares — along with artifacts and multimedia displays on topics such as shipboard life, class distinctions and health conditions. Ledgers show how, in the peak years of 1910-1914, as many as 10,000 immigrants a day passed through.

Italy sent the most immigrants, followed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Russian Empire and the German Empire. After laws were tightened in 1924, U.S. consulates took over most processing and traffic through Ellis slowed to a trickle.

The Baggage Room, where visitors enter, once focused mostly on how immigrants’ possessions were handled a century ago. Now a talking globe illustrates global migrations and an electronic Flag of Faces highlights American diversity.

Upstairs, the Great Hall feels like a rail station with plenty of people but no trains. You can almost hear the echo of foreign languages from long ago. (Of course, that might be the sound of tourists; audio tours are in nine languages.)

The building’s old railroad ticket office now is devoted to pre-1890 Americans, including those whose territory was taken; Africans who were forced into slavery and shipped to North America in the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries; the Irish driven here by famine in the 1840s; and the Chinese who arrived in the 1860s and 1870s.

As a white guy with an Asian American family, I paid special attention to the events of 1882. That year, while the Statue of Liberty was still under construction, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first American law to turn immigrants away on the basis of nationality. (White Westerners, tired of competing for jobs with Chinese immigrants, pushed hard for it.) Later, San Francisco Bay’s Angel Island Immigration Station processed Asian immigrants from 1910 to 1940. It’s now Angel Island State Park.

The exhibits in the pre-Ellis area are handsome and full of data, but how do you tell all the stories that need telling? Ernest Sims, an African American who was visiting from Pittsburgh, told me he would have liked more attention paid to the slave trade. If you arrived as a slave from Africa, he said, “You were here without a choice.”

As for immigration since 1945, those rooms are toward the end of a hallway that some visitors miss. There are video profiles of five immigrant communities (including the Chinese Americans of Monterey Park). There’s a discussion of the bracero program, which brought Mexican workers north legally from the 1940s through the 1960s, and a section addressing illegal immigration.

Though particulars vary, “the reason immigrants came here 100 years ago is the reason immigrants come here today,” Ellis Island ranger Dave McCutcheon told me.

The reason immigrants came here 100 years ago is the reason immigrants come here today.

— Dave McCutcheon, Ellis Island ranger

I was still in the modern immigration wing when I met visitor Armando Marrero, who was frowning. “What do Central and South America have to do with Ellis Island? This is not correct at all,” said Marrero, a New Jersey resident with Puerto Rican roots. Immigration from Europe and from the Americas are such different subjects, Marrero said, that they require separate treatment.

Elsewhere in the post-1945 section was an explanation for what caused immigration demographics to shift so dramatically: the 1965 rewriting of laws that made it easier for non-Europeans to immigrate. As recently as 1960 three of every four (74.5%) of U.S. immigrants had come from Europe. By 2014 that figure had dropped to about one in nine immigrants (11%). By that same year about 50% of the U.S.’ 42.4 million immigrants had come from Latin America, more than 25% from Asia.

Given those numbers, it would seem inevitable that fewer and fewer American families have Ellis Island connections. But the numbers are slippery.

For years, many publications and organizations (including the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation and Save Ellis Island) have suggested that 40% or more of American families can be traced through Ellis Island. But Barry Moreno, an Ellis Island NPS historian and librarian, told me that figure “was made up years ago by some booster, promoter or publicist. It certainly has no basis in fact, either historical or statistical.” If there is a number with solid research behind it, Moreno said, he’s never come across it.

Then again, I suppose the goal of the Ellis Island museum is to take us beyond numbers, to show us faces instead, to help us see ourselves in the stories of others, no matter who arrived by what means.

With that in mind, my last stop in the museum was the American Family Immigration History Center, where $7 buys you 30 minutes of assisted searching through digitized passenger lists from ships arriving at Ellis Island and the Port of New York from 1892 to 1957. (You can also search free from home on the website.)

Because my ancestors reached North America before the 1890s, I didn’t expect much. But with just a few minutes’ help from genealogy research assistant Diana Papa, I’d found the names of my late parents, returning from their Italian honeymoon in June 1955 aboard the Andrea Doria.

And that wasn’t all. Next, Papa showed me one of her favorite passenger-manifest pages — the cast of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, heading home after a European tour in 1892. Among those aboard: three “Indian horsemen” named Eagle Bird, Burns Himself and Crazy Bull.

In other words, there’s no telling whom you’ll find on Ellis Island now.

Twitter: @mrcsreynolds

Follow our adventures: Facebook | Twitter | Pinterest

MORE NATIONAL PARKS

Quiz: How many national parks have you visited?

Discover our desert national parks and rediscover yourself. You can start with Joshua Tree

Manhattan Project National Historical Park tells how and why the U.S. built and used atomic bombs

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.