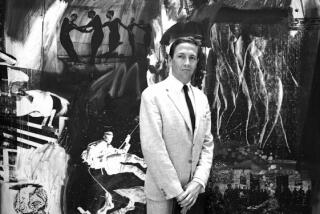

Influential photographer Robert Frank dead at 94

- Share via

Robert Frank, the fiercely independent photographer and filmmaker whose bleak yet poetic book “The Americans” jolted the nation’s self-image and sparked a photographic revolution, has died. He was 94.

In his life and art, the Swiss-born Frank followed his twin muses — intuition and imagination — wherever they led. During a career that spanned nearly seven decades, he shifted from still to moving pictures and back again, sometimes blurring the lines between the two as he experimented with content and form.

His death was confirmed by the Pace-MacGill Gallery in Manhattan, the New York Times reported.

“The Americans,” which was first published in the late 1950s, is considered one of the most influential photography books of the 20th century. Its 83 black-and-white images — largely taken during a series of road trips — made the ordinary seem extraordinary and established what the noted curator John Szarkowski called “a new iconography for contemporary America, comprised of bits of bus depots, lunch counters, strip developments, empty spaces, cars, and unknowable faces.”

Initially derided by many critics, the book “came to be passionately embraced by younger photographers and artists, and then by the public, for its radically innovative subject matter and style,” said Sarah Greenough, senior curator and head of the department of photographs at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, which has mounted two Frank exhibitions and is home to a major archive of his work.

In the ‘50s, the nation liked to think of itself as being as prosperous and wholesome as the picket-fenced suburbia of television shows like “Father Knows Best.” Frank presented a more diverse — and disquieting — view. His book looked “beneath the surface of America,” Greenough told The Times, “revealing issues like racism, skepticism of political leaders and a rapidly rising consumer culture that are still relevant.”

The immigrant photographer had set out to produce, as he put it, “a spontaneous record of a man seeing this country for the first time.” Starting in the East, he and his Leica camera captured people of different races and classes living their lives, from Southern hamlets to Midwestern metropolises to western highways. Observing what others often overlooked, he exposed undercurrents of isolation and angst, discovered beauty in unexpected places and turned mundane scenes — a passing trolley, an elevator ride — into telling portraits of postwar society.

Compared to classic compositions of the day, Frank’s pictures looked rough, as if done on the fly, poorly lighted and oddly framed. But to admirers, such imperfections made the images feel more “true,” while prompting viewers to ponder their deeper meaning.

Frank’s first film, “Pull My Daisy,” a 1959 Beat tale he co-directed with Alfred Leslie, is regarded as an important example of American avant-garde cinema. Many of his other works were intensely personal. “I think I became more occupied with my own life, with my own situation, instead of traveling and looking at the cities and landscape,” he said in the 1986 documentary “Fire in the East: A Portrait of Robert Frank.” “And I think that brought me to move away from the single image, and begin to film, where I had to tell a story.”

Photographer Robert Frank’s seminal 1958 book “The Americans” was, for naysayers, the equivalent of a foreign agent spilling grainy secrets about a nation more unfulfilled than triumphant.

Robert Louis Frank was born in Zurich, Switzerland, on Nov. 9, 1924. He was the younger of two sons of Hermann, a successful businessman, and Regina, the daughter of a wealthy factory owner.

Everyone expected Frank to go into business, too. He had other ideas. In his teens, he became a photographer’s apprentice and worked in several studios, learning about graphics and publishing as well as photography.

During World War II, the Franks, who were Jewish, maintained a safe, if uneasy, existence in neutral Switzerland. After the war, the restless young man decided to leave a homeland he found small and confining. In 1947 he arrived in New York, a city alive with poets, painters and jazz musicians as well as magazines that championed photography as journalism and art. Frank was hired by Alexey Brodovitch, the celebrated art director of Harper’s Bazaar, and spent a short stint on the Bazaar staff before striking out on his own. He traveled extensively in Latin America and Europe, shooting evocative images of people and places that caught his eye.

Frank married artist Mary Lockspeiser in 1950. That same year, he was chosen for a group show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Edward Steichen, Szarkowski’s predecessor as director of the museum’s photography department, was an early admirer.

Another supporter was photographer Walker Evans, a mentor who helped win the Guggenheim fellowship money that financed the trips for “The Americans.”

In 1955 and 1956, Frank drove a used Ford up, down and across the nation. He filled more than 760 rolls of film. “It was hard work,” said Greenough, “and he was frequently harassed because he was a stranger taking pictures in places where strangers weren’t always welcome.”

Back in New York, Frank reviewed thousands of frames and then sequenced his selections, creating what he called a “distinct and intense order” that enhanced their dramatic and thematic impact.

“Les Américains” was first published in France in 1958 by Frank’s friend Robert Delpire. A year later, Grove Press came out with “The Americans,” a U.S. edition that had an introduction by Jack Kerouac. “Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film,” Kerouac wrote, “taking rank among the tragic poets of the world.”

Reviewers were less enthusiastic. While some sounded positive notes, many — especially those from photography magazines — lambasted Frank, accusing him of being misguided, mean-spirited and — perhaps worst of all, given the Cold War climate — anti-American. Popular Photography decried his prints as “flawed by meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposure, drunken horizons and general sloppiness.”

The photographer’s stark, unvarnished photos depicting life in the U.S. are at the National Gallery of Art.

“I do like America,” Frank said in a 2004 documentary, noting that “I became an American.” (He gained U.S. citizenship in 1963.) His project made him realize how “lonely” and “tough” the country could be, he recalled in “Leaving Home, Coming Home: A Portrait of Robert Frank.” “Also, I saw for the first time the way blacks were treated. It was surprising to me. But it didn’t make me hate America. It made me understand how people can be.”

As times changed so did perceptions of Frank. By the end of the 1960s, he was being hailed as a prescient social observer and convention-busting artist who changed the course of modern photography.

“Seeing ‘The Americans’ in a college bookshop was a stunning, ground-trembling experience for me,” artist Ed Ruscha told Tate Etc., the international art magazine, in 2004.

“Frank creates movement with his camera and his subject in a truly original way,” photographer Mary Ellen Mark said in the same issue. “He’s a narrative photographer. Looking at his pictures is like watching a part of film; you can imagine what is happening around the frame.”

Rather than embrace fame, the at-times-reclusive Frank often seemed to do what he could to avoid it. For a while, he thought of “The Americans” as an albatross. “He felt like a rock star expected to sing a certain song,” Greenough said. Eventually, he came to appreciate the book but, loath to repeat himself, he remained eager to try new things.

Indeed, after “The Americans,” Frank turned his attention to dramatic and documentary films and videos. Among the best-known is his controversial look at the Rolling Stones’ 1972 North American tour. The Stones fought to prevent release of the movie with the unprintable title; Frank won the right to screen it under restricted conditions.

In 1972, Frank published the autobiographical photography book “The Lines of My Hand.” He began to create Polaroid art, collages and images constructed, altered and scribbled on.

Robert and Mary Frank separated in 1969. Their daughter, Andrea, died in a plane crash in 1974. Frank expressed his grief in the 1980 film “Life Dances On….” In the 2004 “True Story,” he included scenes from his life and work and correspondence from his son, Pablo, who died in 1994 after a battle with mental illness.

Frank married artist June Leaf in 1975. For decades the couple lived in tiny Mabou, Nova Scotia, and New York.

In 2009, radio interviewer Bob Edwards asked Frank what tips he had for young photographers. “I’m not too much about talking or giving advice,” he said. “ ‘Keep your eyes open’ … that’s what I tell them.”

Wada is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.