- Share via

Every few months after she left the narrow white cottage on Poplar Boulevard, Maria Merritt would slink back to the tree-lined street in El Sereno, find a secluded spot and stare at her old house.

No one had lived there since 2007 when Merritt gave up trying to pay the monthly rent to her landlord, the California Department of Transportation. The state agency had left the house — one of hundreds that Caltrans had acquired for a contentious, on-again, off-again extension of the 710 Freeway — vacant and deteriorating, covering the windows with plywood and “No Trespassing” signs.

Two weeks before Merritt lost her home, she’d lost her job as a secretary in L.A. County’s Department of Mental Health. Once the house was gone, she lost her four children. On and off the streets, suffering from depression and addicted to methamphetamine, Merritt eventually lost her hair when, she suspects, another homeless person poured Nair into her shampoo.

But even as the years passed, the house in El Sereno continued to remind her of a better life.

When she looked at her former home, she’d envision her Christmas decorations on the windows and her daughters running down the sidewalk. She’d imagine the smell of the albondigas and pozole she’d cooked on Sundays.

Fearing the coronavirus outbreak and inspired by a similar occupation in Oakland, homeless residents moved into an El Sereno home owned by Caltrans.

“All the big things that I’ve done. With my job. With my citizenship. With me making the right choices and doing the right things,” recalled Merritt, 57. “Everything happened in that house.”

Then, in March 2020, at the start of a global pandemic, a group of people decided to seize empty, Caltrans-owned homes in the northeast Los Angeles neighborhood. They called themselves “Reclaimers,” arguing that their law-breaking was justified by the scandal of public property left vacant while political leaders ordered residents to stay at home and tens of thousands of people slept on the streets of Los Angeles.

On a drizzly Saturday morning, Merritt, who was living in an encampment nearby, looked on in astonishment as a man and two women occupied a Caltrans house a half-mile from where she’d lived 13 years earlier. Dozens of supporters carried in food and furniture to help them. Maybe they would help me too, she thought.

The next evening, she returned to the cottage on Poplar Boulevard. She saw a half-dozen activists, none of whom she knew, who were there to encourage her and prevent the police from stopping what they were about to do. She witnessed someone hop the fence by the driveway. She heard the crash of glass from the back window of the white cottage. She watched the front door open. She thanked God.

“The home always said, ‘I’m waiting for you,’” Merritt said through tears. “The home said, ‘Come back. Get well. Come back. Get well.’”

::

When Merritt moved into the house in December 1995 it seemed unlikely she’d be there for long. After 40 years of debate, during which Caltrans acquired 460 homes, apartment buildings and other properties in El Sereno and neighboring South Pasadena and Pasadena, the 710 Freeway was on the road to completion.

The route, which aimed to connect L.A.’s ports to the 210 Freeway, had a 4½-mile gap at the northern end. Then-Gov. Pete Wilson, calling the expansion “years overdue,” forged ahead, and it looked like the houses Caltrans had purchased would be demolished.

But Merritt wasn’t bothered by the freeway plans. She was used to moving.

Born in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, Merritt and her four younger siblings were raised in cardboard shelters with dirt floors and no electricity. Her father would be gone for months at a time, working in the fields in the United States, and her mother would disappear for days, leaving Merritt to beg neighbors for food. When she was 10, her mother paid someone to swim her through the Rio Grande and across the border into El Paso.

Nine years later, Merritt came to Los Angeles with a husband and two children. It was an abusive relationship that she eventually escaped, but there were others fueled by partners’ violence and drug use.

When she was in her late 20s, Merritt entered another relationship and was living in an apartment in San Gabriel with her new partner, her two older children and a third born in 1992. She got a job with L.A. County’s mental health department as a temp doing community outreach. It paid better than the housecleaning and fast-food jobs Merritt was used to, and the work gave her the confidence that she could make big decisions on her own.

Merritt was driving to a nearby Target when she first noticed the snug two bedroom on Poplar Boulevard with a “For Rent” sign posted in the yard. She remembers peering inside the front windows.

California transportation officials effectively ended a six-decade battle over the unfinished 710 Freeway this week, recommending against a costly, controversial freeway tunnel that would have been the longest in the state.

“I don’t know what it was,” she said, but “I knew that was going to be my house.”

When Merritt learned that Caltrans owned the house, she also found out that if the freeway wasn’t built, Caltrans tenants would get the first opportunity to buy the properties. Her heart swelled at the thought that Poplar Boulevard might be her forever home, and she convinced her partner to move, proud that they could easily afford the $715-a-month rent.

Ten months after they’d arrived on Poplar Boulevard, Merritt gave birth to her fourth child, a daughter named Kianna.

Merritt still marvels that, as a toddler, Kianna made one corner of the living room her own, always bringing her Legos and Polly Pocket toys there to play.

“I still have dreams to this day of being in that house,” said Kianna, now 27. “That just goes to show how many good memories I had in there.”

A few years after Merritt’s family arrived, the 710 Freeway expansion became mired in litigation once again, buying them more time. Merritt’s relationship ended and her partner moved out, but she remained there with her four children, making memories.

Poplar Boulevard is where her kids helped her study to pass her U.S. citizenship exam. It’s where she was promoted to a full-time job with the county and then promoted again to an executive secretary. It’s where she grilled carne asada by the tall, shady tree in the backyard. It’s where her son, Merritt’s eldest child, learned to play “Pretty Woman” on the guitar in their garage just because Merritt told him she loved the song.

His band serenaded her once they’d perfected the sound.

::

Despite her efforts, the life Merritt worked so hard to build started to disintegrate. She began falling behind on her rent, according to Caltrans’ records, and a horrific accident sent her life into a spiral.

Her former partner and their daughter were involved in a head-on collision in 2004, and Kianna, then 7, was thrown against the dashboard. She fractured her pelvis and her scalp was ripped from her forehead. It took 62 stitches to close the wound.

During her daughter’s monthlong hospital stay, Merritt didn’t leave Kianna’s side. Afterward, Merritt continued to miss days at work. In a deep depression, she began using methamphetamine.

Her sporadic rent payments stopped, and in the spring of 2007, Caltrans filed an eviction lawsuit against her. Agency records showed she owed nearly $37,000. According to case filings, Merritt negotiated a settlement that would allow her to stay in the house if she repaid $15,000 over a few months. But soon after she made the agreement she lost her job.

Two weeks later, Merritt left Poplar Boulevard before Caltrans could send sheriff’s deputies to remove her.

Her children scattered. Her eldest daughter, by then a teenage mother herself, moved in with her boyfriend and took her middle sister with her. Kianna went with her father. Her son moved to Texas, smashing his guitar on the front door of the house before leaving.

“They lost their mother,” Merritt said of her children. “I lost myself.”

Her life became a cycle of drugs, violence and deprivation. She said she was sexually assaulted and ate stale food from trash containers. Mostly, she stayed around El Sereno, even though she was ashamed to walk into the stores where she used to shop. One year blurred into the next. Merritt ended up on The Island, a long-standing encampment on a dirt-filled median in the neighborhood.

Only when the rest of the world was shutting down was Merritt able to seize an opportunity for change.

1

2

3

4

1. Ruby Gordillo, middle, lets herself into a Caltrans-owned home in El Sereno in March 2020 as part of the Reclaimer protests. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times) 2. A group of people assist the Reclaimers move into an empty Caltrans-owned home in March 2020. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) 3. Sisters Meztli Escudero, 8, left, and Victoria Escudero, 10, stand in the window of a vacant house that they and their mother Martha occupied in March 2020. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) 4. Protesters celebrate as a man and two women seize a vacant Caltrans-owned home in March 2020. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

::

In November 2019, a group of homeless mothers in Oakland took over an empty house owned by a house-flipping developer. Inspired by their actions, Roberto Flores, a 76-year-old former Caltrans tenant, decided to organize a similar protest in El Sereno. Flores, who operates a private community center, said Caltrans’ neglect of its homes was unconscionable, especially when vacancies piled up, the freeway project was finally canceled in 2018 and The Island continued to grow.

“Our sense of frustration and indignation was at its limit,” Flores said.

Merritt approached Flores amid the chaos as the first Reclaimers were moving in. She haltingly explained that she used to live on Poplar Boulevard and asked for help getting into a house. Flores looked at Merritt, who by her own account was dirty, drunk and high, and told her that if she cleaned up and came back the following afternoon he’d see what he could do.

Merritt walked for hours to clear her head and strengthen her resolve. She found Flores at the appointed time the next day. He asked her what house she wanted, and Merritt didn’t hesitate.

As the crowd around her cheered, Merritt stepped back into the home on Poplar Boulevard. Flores handed her a set of keys and new locks for the doors.

“Thirteen years,” Merritt said. “Then en un abrir y cerrar de ojos — in a quick second — I’m here.”

But once she was inside and looked past the graffiti in the front room and the smell of mold and mildew, she discovered that in her haste to leave 13 years earlier, she hadn’t collected all her belongings.

Merritt pulled open a kitchen drawer and saw her old spoons. She opened the hallway closet to find a bigger surprise: a Polaroid photo of a long-ago Easter, all of her children gathered with baskets, colored eggs and broad smiles taken in the house’s living room. Kianna, 5 months old, stood in a bouncer chewing a teething ring. At the bottom, Merritt had written their names and the date, March 28, 1997.

Merritt hugged the picture and sobbed.

She was alone and suffering through withdrawal, with no electricity or running water. The chill of the night whipped through gaps in the windows and walls. The stench from the toilet she couldn’t flush became overwhelming. When police banged on the windows and threatened to arrest her, she considered leaving. But the draw of Poplar Boulevard remained too strong.

A month into her stay, Merritt felt stable enough to invite a new partner, Darrel Eckhart, a 58-year-old Army veteran she’d met on the streets, to live with her. Those first days together were among the happiest she’d felt in years. He figured out how to turn on the water and electricity, and helped her find furniture.

But after three months together, Eckhart was killed when a drunk driver slammed into his car parked near The Island. The loss was devastating, and Merritt thought of taking her life.

At her lowest, she would retreat to the same corner in the living room where Kianna used to play as a toddler.

“With my eyes open, I would strive to look for the presence of my daughter and go back to those moments,” Merritt said. “And it worked. It uplifted my heart. It uplifted my soul.”

When her children learned that she was living on Poplar Boulevard again through news reports, Merritt said they were angry she’d broken the law, especially in such a public way.

“They were like, ‘Mom, how dare you? You always taught us you work for what you have. We left the house when you knew that we weren’t able to pay rent. You left to honor yourself, your values. And you went back? Leave,’” Merritt recalled.

Over time, however, some of the resistance softened. One of her daughters left a self-stick note on the front door congratulating her for escaping homelessness. Right before Christmas in 2020, Merritt spent time with Kianna and another daughter, the first time they’d gathered around the holidays in years.

They also celebrated the news that Merritt was going to be allowed to remain in El Sereno, albeit not the house on Poplar Boulevard, which Caltrans had deemed unsafe. Under pressure from activists, the state agency had arranged for the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles to allow the Reclaimers to live — temporarily — in publicly owned homes that had been renovated.

Merritt and 11 others signed rental agreements that would last for up to two years. In January 2021, she moved a half-mile away, holding out hope that she could go back to Poplar Boulevard once the house had been repaired.

::

While Merritt was navigating the highs and lows of her return to the white cottage and subsequent move to another Caltrans property, the Reclaimers were hitting a wall.

On the night before Thanksgiving in 2020, a second coordinated effort to take over additional Caltrans-owned homes in El Sereno failed. Police clad in riot gear used battering rams to enter properties and drag out occupiers while helicopters flew overhead and crowds spilled into the streets. More than 60 people were arrested.

The incident was the last straw for many neighbors, already fed up with drill-wielding outsiders peering into their windows searching for vacant homes. Elected officials came out definitively against the occupations, saying enough was enough. There’s been no organized attempt at house seizures in the more than three years since.

And now, with their temporary rental agreements long since expired, Merritt and the other Reclaimers are facing eviction.

In March 2020, more than a dozen families seized vacant, publicly owned homes in El Sereno and were allowed to stay. Now, some may be evicted.

Tina Booth, an executive with the housing authority, said she’s heartbroken that the Reclaimers did not accept Section 8 vouchers offered when they were living in the homes legally. With those subsidies, Booth said, they could have found apartments of their own and ended their housing insecurity.

Caltrans officials say the group has no right to remain. In recently filed court papers, agency lawyers referred to the Reclaimers as “criminal trespassers” and added that any harm that might befall them because of the evictions would be “self-inflicted.”

But Merritt says the enduring connection to her home is too great for her to leave willingly.

She feels stable and has kicked her drug habit. She takes medicine for her depression, her application for Social Security payments has been approved, and she and Kianna have been working on their relationship.

Kianna has harbored years of hurt over her mother not being there for her. Her voice still breaks when remembering that Merritt missed her high school graduation.

Now they talk nearly every day.

“Any time she can get with me, she loves that,” Kianna said. “It’s helping her a lot. It’s healing me as well.”

Meanwhile, Merritt vacillates between despair at the prospect of her eviction and elation when she dreams of returning to Poplar Boulevard.

She remembers what she learned 29 years ago — if the freeway expansion was canceled, Caltrans tenants could buy their homes. That process has now begun. Under the rules outlined in the contracts, low-income families are allowed to purchase them at a discount, the only way they’d be able to afford property in El Sereno, where median home values top $800,000.

1

2

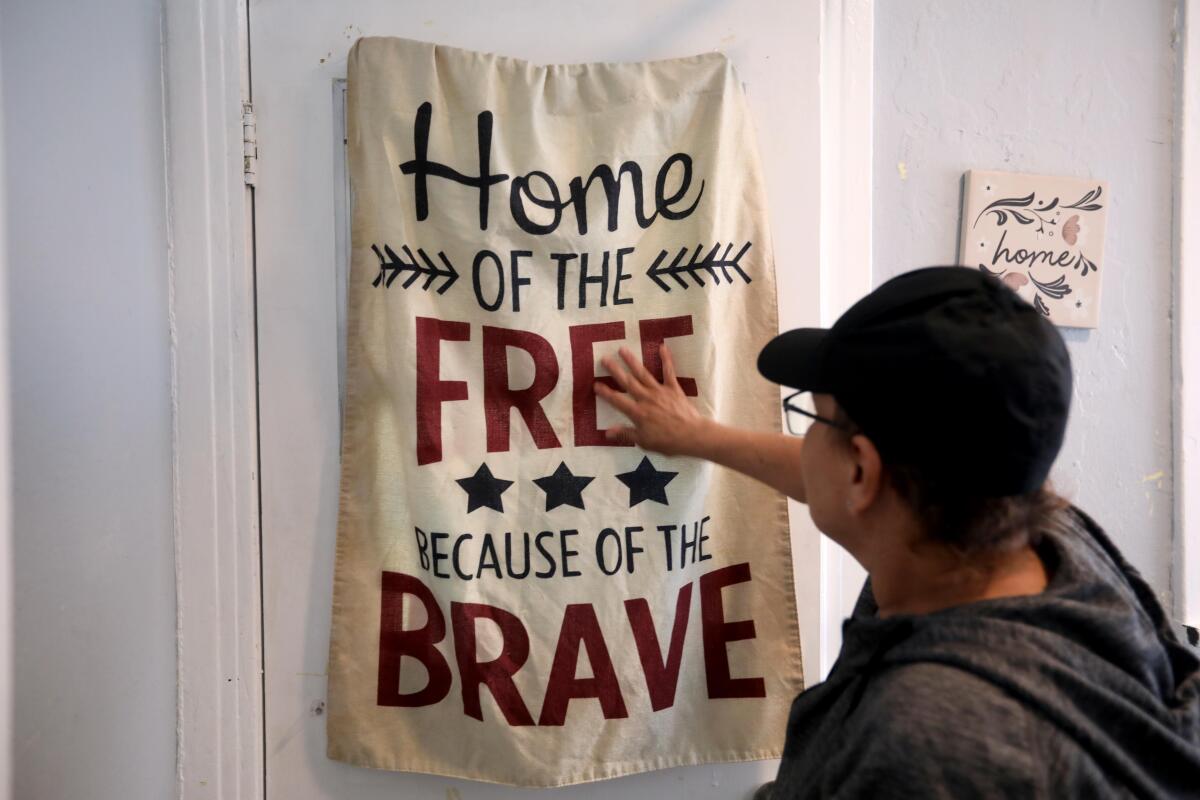

1. Maria Merritt touches a banner she’s hung in her home in El Sereno. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) 2. Maria Merritt puts up an abortion rights sign on a mirror in her home. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

According to Caltrans, Merritt doesn’t qualify for the deal, but she’s pleading with the agency for the opportunity to buy her old home. Merritt thinks she and her children could pool their money, and even pay back the rent she owes from 2007.

“I want to leave that house to my grandkids,” Merritt said. “I want them knowing that Grandma didn’t quit on them.”

If she’s able to move into the white cottage on Poplar Boulevard for the third time, Merritt is certain it would be hers for good.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.