- Share via

In summer 2020, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation was ramping up its fight with the city of Los Angeles over housing homeless people.

Under Michael Weinstein’s leadership, the powerful nonprofit was pursuing a lawsuit alleging the city illegally denied funding for an affordable housing project that the foundation was proposing. Its staff sent email after email to code enforcement and housing officials pressing them to sign off on repairs at the organization’s residential hotels on skid row. The organization even purchased a full-page advertisement in The Times castigating Mayor Eric Garcetti for not helping.

Into the fray stepped Kevin de León, the area’s incoming council member who had been elected but not yet taken office. He telephoned Matt Szabo, Garcetti’s then-deputy chief of staff, “about the Weinstein situation,” Szabo wrote in an Aug. 4, 2020, email to his colleagues. The councilman-elect, Szabo said in the email, “wants to engage and come up with a solution.”

Less than two weeks later, city records and interviews show, Szabo arranged a video call for De León with a cadre of city department heads and high-ranking mayoral staffers.

But those in the meeting didn’t know that De León’s interest in the AIDS Healthcare Foundation’s efforts went beyond that of a future council member. In fact, he was a consultant working for the foundation, a job that would pay him more than $100,000 in the six months prior to his taking office.

Five city officials who attended the briefing or were involved in organizing it told The Times they were unaware of De León’s employment at the time with the foundation.

“I had no idea there was a business relationship between them,” William Chun, then-deputy mayor of economic development for Garcetti, said in an interview. “That’s troubling to hear because you don’t know if he’s acting as councilmember-elect or as a paid consultant. City staff would respond differently depending on who makes the ask.”

Political ethics experts said that De León’s relationship with the foundation and failure to disclose his financial ties raise a potential conflict-of-interest concern. They believe his actions could have left city staffers with uncertainty about whose interests he was serving — the city’s or his then-employer’s.

“His responsibility is if he were to meet with them, he would have to announce that he’s paid by that organization and therefore has their interest as a higher priority than the city’s,” said Ann Ravel, an attorney and former chair of the Federal Election Commission and the California Fair Political Practices Commission.

“It’s pretty stunning. This is really unethical.”

Ravel said De León should recuse himself from voting on matters related to the AIDS Healthcare Foundation because of the council member’s past relationship with the organization.

De León did not respond to a written list of questions from The Times about the meeting and his ties to the foundation. He said in a written statement that he acted to address his district’s most pressing issue.

“Before taking office, I was asking myself the same question thousands of Angelenos across the city were asking themselves in the midst of a homeless crisis and global pandemic: Why are there hundreds of empty units in skid row while thousands of people in that neighborhood languish and die on the streets?” De León wrote. “So I spent many months even before I was sworn in convening dozens of meetings with city officials, nonprofits and community leaders around homelessness.”

De León’s office provided calendar records to The Times showing more than a dozen such meetings.

For his part, Weinstein said he was unaware of De León’s August 2020 gathering with city officials.

“No action was taken by the city to the best of my knowledge,” Weinstein said in response to written questions from The Times.

District 14 voters elected De León to the City Council in March 2020, but he didn’t take office until October. Two months after his election, the foundation hired De León, according to foundation spokesperson Ged Kenslea, who said the contract ended the day before De León was sworn in.

Foundation executives said they paid De León $109,231 for his work. De León declined to confirm his salary. Economic disclosure forms required the council member only to check a box saying he earned “over $100,000.”

To understand De León’s financial ties with the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, an influential nonprofit and prominent landlord in his district, The Times reviewed thousands of pages of emails, text messages and meeting notes obtained through the California Public Records Act, along with depositions and other court filings, and campaign finance and lobbying disclosures. The Times also conducted interviews with more than a dozen current and former city officials.

After De León took office, the foundation and the council member promoted each other’s ambitions. Weinstein hosted a fundraiser for De León’s failed 2022 mayoral bid and 14 foundation employees contributed about $9,000 to that campaign — the largest total of any individual nonprofit or business.

On its website, the foundation showcases a video advertisement De León made in 2021 in front of a foundation logo championing the expansion of its real estate portfolio. It’s still there despite last fall’s scandal involving a leaked tape of a racist and offensive conversation over redistricting that led to widespread condemnation, including President Biden and others calling for De León’s resignation.

The politician’s connections to the foundation have raised uncomfortable questions surrounding De León’s handling of problems at residential hotels the foundation owns in his district.

For years, city code enforcement and county public health inspectors have scrutinized the properties and cited violations at several of them that included cockroach infestations, mold, unpermitted construction, faulty electricity and broken plumbing. The foundation recently agreed to pay at least $832,000 to settle a civil case filed by 18 elderly and disabled tenants at the Madison Hotel on skid row over a chronically broken elevator. A class-action lawsuit claiming overall uninhabitable conditions at the Madison remains pending.

In late 2021, De León’s office learned that dozens of residents at foundation properties were protesting their living conditions. But after a member of his staff, Christopher Antonelli, visited a property to look into the matter, De León questioned him, saying that he was getting “angry calls and texts” that were “coming from the top” at the foundation. Ultimately, Antonelli abandoned the investigation due to litigation over one of the properties on the advice of the city attorney’s office, a De León spokesperson said.

In his statement to The Times, De León said that he showed no favoritism toward the foundation in addressing tenant complaints.

“In my office, when it comes to protecting tenants, I have a track record that shows we work to ensure every tenant’s right to decent housing — no exceptions,” De León said.

His office provided email correspondence from the last six months showing that staff members had referred foundation tenants to city enforcement agencies and monitored their complaints.

The largest AIDS organization in the world, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation generates $2 billion a year in revenue largely from its chain of pharmacies and clinics. In 2017, it began working in housing, with Weinstein blaming luxury real estate developers for driving gentrification and unaffordability in Los Angeles, the nonprofit’s global headquarters.

That year, the foundation created a new division called the Healthy Housing Foundation and purchased the Madison, a nearly century-old, 200-unit residential hotel, for $8 million. The plan was to refurbish it and charge low rents — $400 a month in many cases — to give those at risk of homelessness a safe and affordable place to live. The Madison was the first of more than a dozen similar properties on skid row and in Hollywood and other L.A. neighborhoods the foundation now owns.

AIDS Healthcare Foundation has said it can house homeless people better than the city. But, in a new lawsuit, tenants allege slum-like conditions.

In 2018, the same year De León termed out of the state Legislature after more than a decade, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation sponsored a ballot initiative to expand rent control across California. Even though the foundation dropped $23 million, it was outspent 3 to 1 by landlord interests and lost by nearly 20 percentage points.

De León, who served 3½ years as leader of the state Senate, endorsed the initiative and supported many of the foundation’s housing policies.

In March 2020, De León easily topped a five-candidate field to replace the termed-out Jose Huizar, the council member then representing skid row, downtown and adjacent Eastside neighborhoods. Because he won a majority of the votes, De León was elected without a runoff.

Nearly four months later, federal prosecutors arrested Huizar, alleging he accepted at least $1.5 million in bribes from developers to promote their projects. The City Council suspended Huizar — who later pleaded guilty to racketeering and tax evasion charges — and some community members called for De León to take office sooner than scheduled.

The councilman-elect said he needed to tend to an ailing family member and waited until October to be sworn in.

One day after De León’s victory, Madison tenants filed a class-action lawsuit alleging vermin filled their homes and the plumbing, heating and electricity failed regularly.

Weinstein agreed that the problems — the broken elevator in particular — were legitimate, but at a news conference he blamed the city for failing to permit planned upgrades. The foundation’s concerns intensified as the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, diverting the city’s attention away from its buildings, email records from the city show. Late last year, the city and public utility agreed to pay the foundation $100,000 to settle claims that they delayed improvements to the Madison’s elevator.

“Something has to be done to cut through the city’s bureaucracy,” Weinstein wrote in an April 2020 email to a staff member for Garcetti. “I think you know that we are facing a class-action suit because of the city’s inaction. Please, please, please help us.”

In May, the foundation hired De León as a consultant to provide “strategic advice regarding legislative activities and policy on fair housing policies and initiatives,” said Kenslea, the foundation spokesperson.

Neither the foundation nor De León would provide details on the specific work he did.

Residents of a skid row hotel resolve a long-running dispute with its owner, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, over a chronically broken elevator.

When The Times first asked Kenslea for De León’s salary in late 2020, he refused, saying the foundation’s contracts were confidential. In response to questions for this story, Weinstein said the foundation would share the contract if the council member agreed, but De León declined.

De León also reported receiving between $10,000 and $100,000 in income from each of three community and environmental nonprofits and more than $100,000 each from USC, where he was a distinguished fellow addressing pollution issues, and from the electrical workers union, where he worked as a strategic advisor, according to a required statement of economic interests he filed in December 2020.

At minimum, De León earned $339,231 through consulting in the 9½ months before he took office, according to the statement and the salary the foundation provided. Last year, De León made about $218,000 as a councilman, according to the city clerk’s office.

After De León first approached the mayor’s office in August 2020, Jeff Millman, a senior advisor to Garcetti, emailed colleagues inquiring about the situation at the Madison because “Councilmember-elect de Leon was asking about it.”

Some worried the meeting could venture into sensitive matters, including the city’s legal strategies. The foundation had sued Los Angeles at least six times in the previous year, including a pending suit challenging its rejection by the city’s homeless housing bond program.

“If this is still an active lawsuit against the city, then we shouldn’t be talking to anyone about this,” Sean Spear, then an assistant general manager in the housing department, wrote to his colleagues. Spear recommended looping in the city attorney’s office. The foundation later lost the lawsuit over the bond money.

But other city officials such as Chun, the Garcetti deputy, were hopeful. The meeting, he wrote in an email to the city’s planning director, stemmed “from Michael Weinstein complaining to [De León] that city departments are holding up his redevelopments in downtown.” This was a chance to set the record straight, Chun added.

The discussion wasn’t particularly memorable. One city official who requested anonymity to avoid alienating a council member said that De León did not have specific demands and mostly just listened to a presentation about the status of the foundation’s properties.

Ann Sewill, the head of the city housing department, was invited and had asked her staff to provide information about building conditions beforehand, city emails show. She told The Times she doesn’t recall any details from the briefing or even attending, but she said she did not know about De León’s financial ties to the nonprofit at that time.

“I wasn’t aware he was being paid,” Sewill said. “I would’ve assumed I was dealing with the councilmember-elect.”

Besides Chun and Sewill, three others who were in attendance or involved in planning for it told The Times on condition of anonymity that they didn’t know De León was being paid by the foundation.

Even if De León didn’t make any requests of city employees, the circumstances would still be concerning, said Jessica Levinson, a professor at Loyola Law School and former president of the city’s Ethics Commission. Aside from the uncommon access to high-level officials he received, De León put city staff at risk of disclosing information that could have harmed their litigation or code enforcement strategies to the benefit of his employer, she said.

“We’re worried that Kevin de León is making decisions that are helpful for AHF and not for his constituents and not for the city,” Levinson said. “Conflicts of interest always come down to you have divided loyalty. Are you in a position where you’re serving two masters and one of them is not the public?”

At the time of the meeting, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation was funding another statewide initiative to expand rent control, ultimately spending $40 million on the losing effort. De León appeared in video advertisements supporting the initiative and accompanied campaign officials to a meeting with The Times’ editorial board.

But the public wouldn’t have known about his paid advocacy from looking at the initiative’s campaign disclosure forms, which are filed regularly in advance of election day.

Instead, the foundation reported De León’s work only in footnotes of another batch of filings unrelated to the initiative. That had the effect of delaying any public disclosure of De León’s paid involvement with the foundation until the week before he took office and not revealing the full amount of his work on the initiative — reported as $89,231 — until months after the election.

Whether the campaign adequately reported De León’s payments is part of an ongoing investigation into the 2020 rent control initiative campaign by the California Fair Political Practices Commission, which enforces the state’s campaign finance laws, the agency confirmed to The Times.

Ravel said a key purpose of the laws is to require transparency surrounding who is being paid so that voters can be aware prior to casting their ballots, calling the circuitous disclosure of De León’s payments “clearly problematic.”

Weinstein said that executives “considered his work to be for the foundation and for renters’ rights in general” and that all campaign disclosures were proper.

Upon taking office, De León maintained close relations with the foundation, speaking at its housing events and inviting foundation officials to his news conferences.

A month after his inauguration, De León praised the organization after one of its buildings was designated a historic property. He said the city and other nonprofits should follow its lead.

“Our approach to reducing homelessness must be all hands on deck, so AHF and the Healthy Housing Foundation are to be commended for their innovative and cost-effective approach,” the council member said in a foundation news release.

But in October 2021, tension over De León’s coziness with the AIDS Healthcare Foundation surfaced. A former foundation employee turned critic named Karla Leiva contacted De León’s staff about plumbing, mold, vermin and elevator problems at multiple foundation properties. Ultimately, Antonelli, De León’s downtown-area director, agreed to meet Leiva at the Madison the afternoon of Dec. 1 and speak to tenants directly.

When they arrived, chaos erupted.

Foundation staff members wouldn’t let Antonelli and Leiva sign in to the building, Antonelli recounted in a February 2022 deposition obtained by The Times.

As Antonelli and Leiva started speaking with tenants, staffers called the police and began taping the two on their cellphones.

Despite this interference, Antonelli recorded a video of cockroaches and other insects crawling all over one tenant’s dresser drawer. He witnessed residents with obvious disabilities struggling to climb the stairs because the elevator was broken. Tenants shared concerns about mold and their safety. Antonelli concluded that the Madison had “serious habitability issues,” he said in the deposition.

The AIDS Healthcare Foundation has spent tens of millions on pro-tenant causes. Yet elderly and disabled tenants at one of its buildings complain they have spent months at a time without a functioning elevator.

But after about 40 minutes, two Los Angeles Police Department officers arrived and asked what Antonelli was doing there.

Frustrated, Antonelli explained who he was and told the officers the foundation was hindering his work.

“Our visit was impeded by not only the AIDS Healthcare Foundation staff following us around with a camera, but also impeded by AIDS Healthcare Foundation staff calling the police on us to do precisely what happened. And that was to kick us out,” Antonelli said in the deposition.

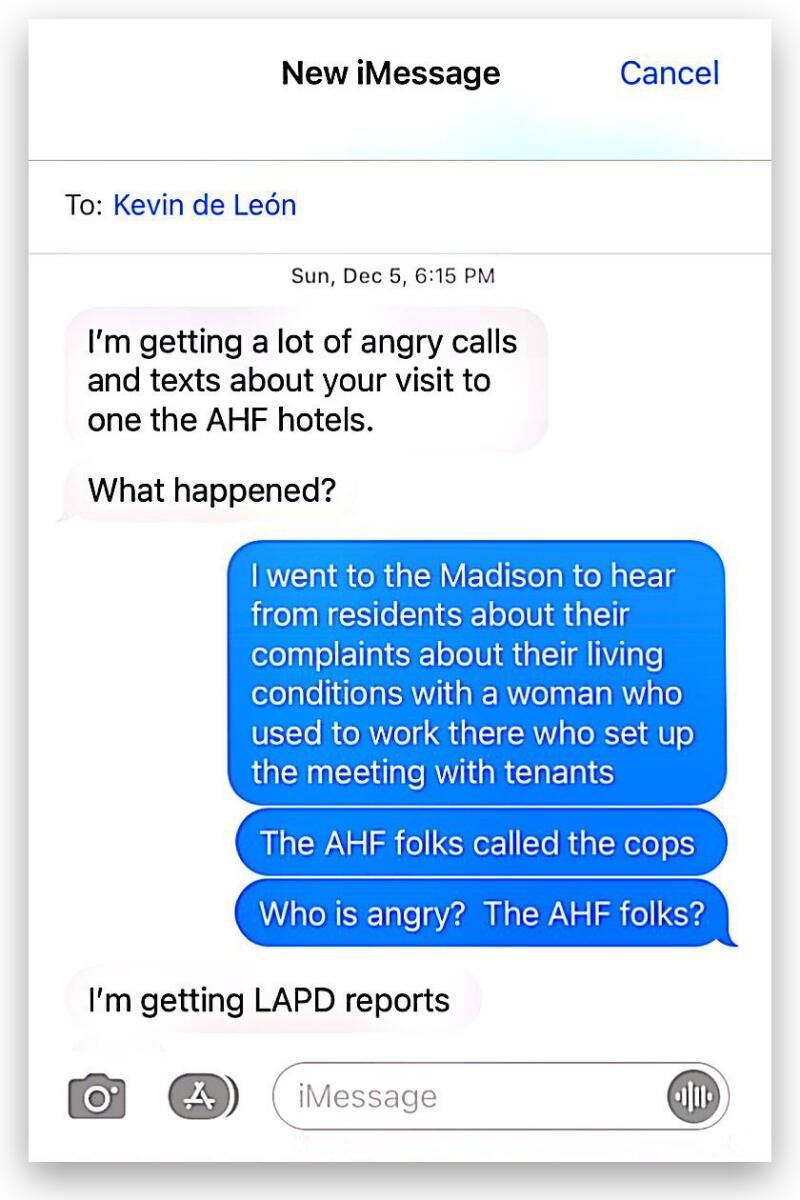

Four days after the episode, he received a text from De León.

“I’m getting a lot of angry calls and texts about your visit to one [of] the AHF hotels,” De León wrote. “What happened?”

Antonelli summarized his experience and asked whether it was people at the foundation who were angry.

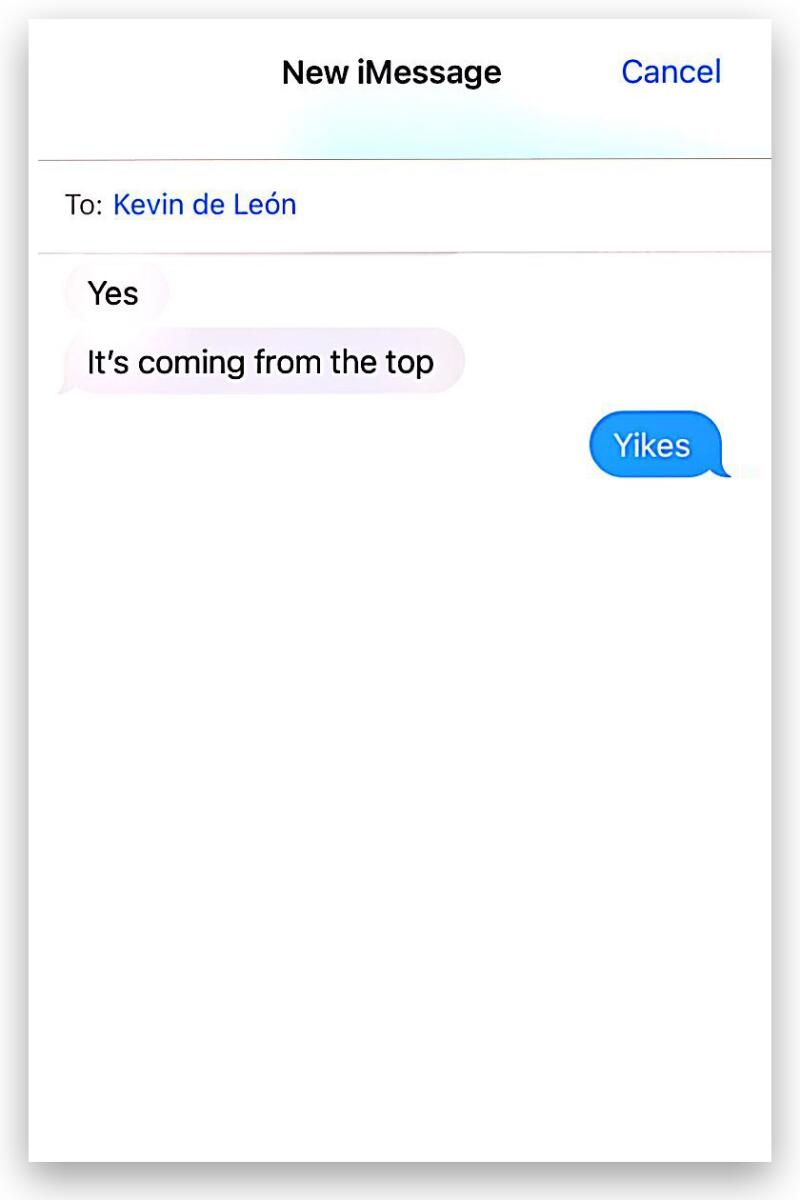

“Yes,” De León replied. “It’s coming from the top.” De León added that he was receiving reports from the police about the incident.

“Yikes,” Antonelli wrote. He added: “If the AHF folks continue to call and text, I can certainly provide more context.”

“We are not looking to harm AHF,” Antonelli continued. “We are trying to find out what’s going on and how to help mitigate concerns.”

De León didn’t respond, according to text message records the city provided to The Times.

Initially, De León’s office did not disclose this exchange. In September, De León’s spokesperson, Pete Brown, said that the council office had turned over all internal and external written communications about the foundation’s residential hotels.

“No documents have been withheld or redacted,” Brown told The Times in response to a public records request.

Only after a Times attorney sent a legal demand letter noting that Antonelli had mentioned texting with his boss in his deposition did the city turn over that exchange and other previously undisclosed messages. De León’s office continues to maintain that the council member hasn’t texted or emailed with Weinstein or any foundation employee about the Madison incident or any of its properties. Brown confirmed that a foundation staff member called De León to complain about Antonelli’s visit but declined to name them. Weinstein said it wasn’t him.

The morning after their visit, Leiva emailed Antonelli a petition signed by more than 50 tenants from the Madison and two other foundation residential hotels nearby, the King Edward and the Baltimore.

Antonelli followed up with King Edward tenants but said in his deposition that he spoke with them only by phone so as to avoid a repeat of what had happened at the Madison. Residents told him that this building’s elevator also failed regularly, they often lacked hot water, and urine and feces were spread on the floor, according to his notes from the conversations.

Antonelli believed the circumstances were fraught no matter what. People at risk of homelessness lived in the properties, and he said in the deposition that he and De León’s chief of staff, Jennifer Barraza, discussed how closing the buildings could force people onto the streets.

Nevertheless, Antonelli said in the deposition that he was planning to contact the foundation about resolving the problems in its buildings. He prepared a letter to the foundation outlining what he had found and requested that management address the habitability issues, according to a draft provided to The Times by De León’s office.

But the city attorney advised against the communication since foundation attorneys had subpoenaed Antonelli for the deposition in the Madison class-action case, De León’s spokesman said, and the letter was never sent.

“Communications between myself, my office, and the AIDS Healthcare Foundation is extremely precarious, and I’m very cautious,” Antonelli said in the deposition.

Just six weeks after foundation employees called police on his staff member, De León stood beside the AIDS Healthcare Foundation’s leadership.

On the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday weekend in 2022, Weinstein held a groundbreaking for a 216-unit low-income housing development next to the Madison called Renaissance Center.

De León spoke at the event, and photos show the council member celebrating alongside Weinstein, shovels in hand.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.