In a remote corner of California, a state program successfully shelters homeless people

- Share via

CRESCENT CITY, Calif. — On a rainy winter morning, Jamie Hayden stopped in to visit with Diane Timothio. A case manager in Del Norte County on California’s remote northern coast, Hayden comes by often, sometimes staying for hours, to work with Timothio.

Work can mean different things: going to doctor’s appointments, building her comfort level with eating at a restaurant, or listening to Timothio recount stories about the past. Right now, the pair are working on using the internet, so there’s a lot of time spent on web searches.

“Is Billy Graham still alive?” Timothio asked. “We Googled that,” Hayden replied, reminding her the answer is “no.” “I’m sorry I won’t get to meet him,” Timothio said, her voice wistful.

Timothio loves religions, their rituals, and says she’s been baptized many times, including as a Latter-day Saint and a Jehovah’s Witness. She also has practiced as a Hindu and joined the Hare Krishnas for a while. She’s joined so many spiritual groups over the years, she said, because she loves that feeling of rebirth, a new start. “It’s like you can see God looking at you: ‘Finally getting your s— together, huh, Diane?’”

Early in the pandemic, county workers found Timothio, now 76, at a low-budget motel in rough shape. She was showing signs of dementia and had trouble walking because of osteoporosis in a hip. In recent years, her only real medical care had come via the local emergency room, where she was a regular visitor. She’d recently left an apartment after a fire. Then there was COVID-19, and the hotel she was staying in wanted her out. Timothio had nowhere to go.

Rural, isolated and immense, Del Norte is home to one of the nation’s largest undammed rivers and some of the world’s only remaining acres of virgin redwood forest. Fewer than 28,000 people are spread across the county’s 1,000 square miles, land mostly owned by the state or the federal government.

Coastal Highway 101 runs right through Crescent City, the county’s only real town. People who are homeless in the region tend to gravitate here because it’s hard to survive anywhere else. “People need to eat,” said Heather Snow, the county’s director of health and human services.

By California standards, the homeless population in Del Norte is small. According to the most recent survey, there were about 250 people without shelter in 2020. That is almost certainly an underestimate, but, still, the figure pales in comparison to cities in the Bay Area and Southern California, with their tens of thousands living unsheltered.

California’s spiraling housing crisis is often understood through the lens of its big cities, where the sheer number of people who need assistance can quickly capsize the programs designed to move people into housing. But before the pandemic, helping people find shelter in Del Norte had been an insurmountable problem for Snow and her colleagues, as well.

There’s not enough housing in general in Del Norte, let alone for people with precarious finances. Snow lived 30 minutes north, in Brookings, Oregon, when she started her job six years ago. It took years to find somewhere closer to live. And there’s never been a homeless shelter anywhere in the county, as far as she knows.

As hotels shift away from sheltering homeless people as part of Project Roomkey, Los Angeles is racing to distribute thousands of rental vouchers it received from various stimulus bills.

For several years, Snow has used county funds to rent rooms at a local motel to temporarily house people at risk of becoming homeless. Sometimes they’d been released from a psychiatric medical hold or were trying to get out of an abusive relationship. Sometimes they needed a temporary sober-living environment. The county spent $820,000 on those rooms from July 2015 through June 2020. “It was a public health emergency before is the truth,” Snow said. “People just didn’t see it that way.”

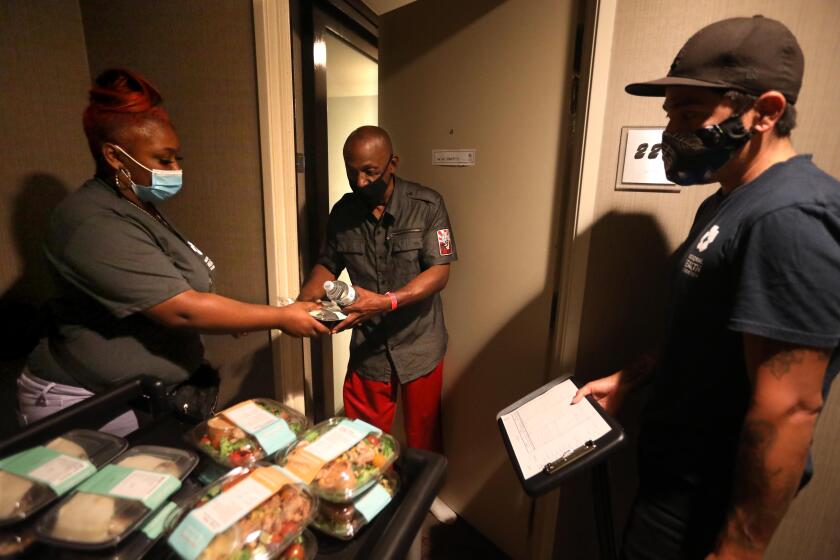

After the pandemic came to town, Snow and her colleagues began using the motel to house people like Timothio who were at high risk for serious illness and had no safe place to live, as well as people who needed a safe place to quarantine after a COVID-19 exposure.

That’s how Reggie and Sandy Montoya ended up there with their 25-year-old son, Cruz. They’d lost their home well before the pandemic began and were making do in a fifth-wheel trailer that was parked behind a restaurant. In May 2020, Cruz was exposed to one of the earliest coronavirus cases in the county at his job at a nonprofit program for disabled adults, and public health workers quickly realized his home wasn’t suitable for quarantining. They brought the whole family to the motel.

Since then, it has become home, and for as long as they want it to be. In October 2020, the state awarded Del Norte County $2.4 million to buy the 30-room motel and turn it into affordable housing through Project Homekey, a statewide initiative spearheaded by Gov. Gavin Newsom to help counties buy old motels and other buildings and turn them into permanent housing. Snow said there’s enough space to accommodate about 17% of Del Norte County’s homeless residents and families.

The motel is nestled in a median between the north- and southbound lanes of Highway 101 and is flanked by grocery stores, fast-food restaurants, a laundromat and a drugstore. It’s not far from the police station and county health services. To Snow, it’s an ideal location for people like the Montoyas who don’t have a car.

In the application to the state, Snow provided documents showing the county could maintain the program for decades, explaining how the site would be run and who would get housing. “I have my master’s in social work. I’m not a real estate tycoon,” Snow said. “This is out of my comfort zone, but it’s what the situation is calling for.”

County officials had to agree to the purchase, and the political pushback was quick to foment, Snow said. A small group of residents staged protests, and city officials asked the county to deny the purchase, saying, among other things, that they didn’t want to lose the motel’s contribution to the tax base. Ultimately, though, Project Homekey’s design worked to Snow’s benefit, offering a lot of money and a narrow window in which to accept it. Snow got to work explaining her vision to county supervisors, and four of the five voted yes.

Interviews statewide reveal a new magnitude of hardship and indignity for tens of thousands of people living on the streets, as COVID-19 upended promises made early in 2019.

Today, the 30 motel rooms in Del Norte are among the more than 7,000 new housing units the state says it has created through Project Homekey in two years. In late January, the Newsom administration announced that an additional $14 billion will be spent in 2022 on a mix of housing units and mental health treatment.

Some people have stayed at the Legacy, as the county renamed the motel, and then moved on to new homes after finding their footing. Others have housing vouchers and jobs but can’t find another place to live. And some, like the Montoyas, have become long-term tenants.

Sandy, 54, and Reggie, 60, have been together nearly 40 years. They met in Sandy’s hometown of Santa Rosa and had been together for several years when Reggie heard the salmon fishing was awesome farther north and came up to try his hand in the Klamath River. They eventually moved to Crescent City, where they’ve lived for two decades, working odd jobs. They’ve had several homes over those years, and many periods without one. Reggie described himself as chronically homeless and said health crises, bouts of depression and drug use have knocked the couple down from time to time.

Reggie and Sandy have concerns about living in the Legacy. They loathe living under someone else’s rules, and after all the months of eating out of a microwave, Sandy desperately misses Reggie’s cooking. “His biscuits and gravy is heavenly. His lasagna is out of this world,” she said.

Some of the other tenants use drugs, and they’ve seen violent outbursts, like the time in December when a neighbor’s tires were slashed. Early on, a woman upstairs thumped around in boots at all hours of the night. After an initial confrontation, they worked it out, eventually becoming friends. But then she moved out and fatally overdosed on fentanyl, they said. They miss her immensely.

Even with all that, they describe their new home as a godsend. “I make it out like a horror show,” Reggie said. “But if it wasn’t for this place, I would probably be dead right now.”

Their room has sheltered them from the cold, wet winters and from the virus. A coming remodel will transform the rooms into functional apartments with kitchens. Their dogs can stay, and they are saving up for a car. Reggie loves that the county therapist he’s seeing for depression always knows where to find him.

Timothio also moved in early in the pandemic. It did not go well initially. Her thoughts were disorganized, and she couldn’t take care of basic tasks like bathing. Several months into her stay, she had trashed her room and was barely getting by.

That’s when Snow and her colleagues from the behavioral health department got involved, navigating through layers of bureaucracy to obtain Timothio’s medical records, get her signed up for government assistance, and ultimately have her placed under county conservatorship. They coaxed her to doctor’s appointments and helped her get on medication for mental health issues.

Timothio began sharing with Hayden details of her traumatic and complicated past. The abusive family members. The children she lost custody of decades before. The violence she’d experienced over decades spent unsheltered. The bouts of deep depression. She uses a refrain when she tells those stories: “I’ve been raped, robbed and mugged, left for dead on the side of the road.”

These days feel calmer. “I just want to stay in one spot,” Timothio said. Hayden had brought her watermelon and grapes, two of her favorite foods, and they were watching old black-and-white Westerns on TV, researching actors and musicians famous in the 1950s.

Timothio recently looked at a photograph of herself from the early days at the motel, sprawled on a bed, sheets askew, surrounded by candy and dirt. She told Hayden she didn’t recognize the woman in it. That wasn’t her anymore.

Hayden stayed a couple of hours and before she left reminded Timothio that a home health aide would come the next day to assist her with chores. Hayden marveled at how, just a few months before, Timothio wouldn’t let anyone in her room. Now, the room was clean, and Timothio was taking her medication and voluntarily going to doctor’s appointments. True, she still wore sunglasses inside and kept the blinds drawn tight. But she felt safe enough to welcome strangers into her home.

This story was produced by KHN (Kaiser Health News), one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation).

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.